Griselda's Sisters: Wifely Patience And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Popular British Ballads : Ancient and Modern

11 3 A! LA ' ! I I VICTORIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SHELF NUMBER V STUDIA IN / SOURCE: The bequest of the late Sir Joseph Flavelle, 1939. Popular British Ballads BRioky Johnson rcuvsrKAceo BY CVBICt COOKe LONDON w J- M. DENT 5" CO. Aldine House 69 Great Eastern Street E.G. PHILADELPHIA w J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY MDCCCXCIV Dedication Life is all sunshine, dear, If you are here : Loss cannot daunt me, sweet, If we may meet. As you have smiled on all my hours of play, Now take the tribute of my working-day. Aug. 3, 1894. eooccoc PAGE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xxvii THE PREFACE /. Melismata : Musical/ Phansies, Fitting the Court, Cittie, and Countrey Humours. London, 1 6 1 i . THE THREE RAVENS [MelisMtata, No. 20.] This ballad has retained its hold on the country people for many centuries, and is still known in some parts. I have received a version from a gentleman in Lincolnshire, which his father (born Dec. 1793) had heard as a boy from an old labouring man, " who could not read and had learnt it from his " fore-elders." Here the " fallow doe has become " a lady full of woe." See also The Tiua Corbies. II. Wit Restored. 1658. LITTLE MUSGRAVE AND LADY BARNARD . \Wit Restored, reprint Facetix, I. 293.] Percy notices that this ballad was quoted in many old plays viz., Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the xi xii -^ Popular British Ballads v. The a Act IV. Burning Pestle, 3 ; Varietie, Comedy, (1649); anc^ Sir William Davenant's The Wits, Act in. Prof. Child also suggests that some stanzas in Beaumont and Fletcher's Bonduca (v. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland, Hitherto

1 ifl ANCIENT OF THE NOETH OF SCOTLAND, HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED. explanatory notes, By peter BUCHAN, COKRESFONDING ME3IBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. " The ancient spirit is not dead,— " Old times, wc trust, are living here.' VOL. ir. EDINBURGH: PRINTED 1011 W. & D. LAING, ANI> J, STEVENSON ; A. BllOWN & CO. ABERDEEN ; J. WYLIE, AND ROBERTSON AND ATKINSON, GLASGOW; D. MORISON & CO. PERTH ; AND J. DARLING, LONDON. MDCCCXXVIII. j^^nterct! in -Stationers i^all*] TK CONTENTS V.'Z OF THK SECOND VOLUME. Ballads. N'olcs. The Birth of Robin Hood Page 1 305 /King Malcolm and Sir Colvin 6 30G Young Allan - - - - 11 ib. Sir Niel and Mac Van 16 307 Lord John's Murder 20 ib. The Duke of Athole's Nurse 23 ib. The Laird of Southland's Courtship 27 308 Burd Helen ... 30 ib. Lord Livingston ... 39 ib. Fause Sir John and IMay Colvin 45 309 Willie's Lyke Wake 61 310 JSTathaniel Gordon - - 54 ib. Lord Lundy ... 57 312 Jock and Tarn Gordon 61 ib. The Bonny Lass o' Englessie's Dance 63 313 Geordie Downie . - 65 314 Lord Aboyne . 66 ib. Young Hastings ... 67 315 Reedisdale and Wise William 70 ib. Young Bearwell ... 75 316 Kemp Owyne . 78 ib. Earl Richard, the Queen's Brother 81 318 Earl Lithgow .... 91 ib. Bonny Lizie Lindsay ... 102 ib. The Baron turned Ploughman 109 319 Donald M'Queen's Flight wi' Lizie Menzie 117 ib. The Millar's Son - - - - 120 320 The Last Guid-night ... 127 ib. The Bonny Bows o' London 128 ib. The Abashed Knight 131 321 Lord Salton and Auchanachie 133 ib. -

Oral Tradition 29.1

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (2014):47-68 Voices from Kilbarchan: Two versions of “The Cruel Mother” from South-West Scotland, 1825 Flemming G. Andersen Introduction It was not until the early decades of the nineteenth century that a concern for preserving variants of the same ballad was really taken seriously by collectors. Prior to this ballad editors had been content with documenting single illustrations of ballad types in their collections; that is, they gave only one version (and often a “conflated” or “amended” one at that), such as for instance Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry from 1765 and Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border from 1802. But with “the antiquarian’s quest for authenticity” (McAulay 2013:5) came the growing appreciation of the living ballad tradition and an interest in the singers themselves and their individual interpretations of the traditional material. From this point on attention was also given to different variations of the same ballad story, including documentation (however slight) of the ballads in their natural environment. William Motherwell (1797-1835) was one of the earliest ballad collectors to pursue this line of collecting, and he was very conscious of what this new approach would mean for a better understanding of the nature of an oral tradition. And as has been demonstrated elsewhere, Motherwell’s approach to ballad collecting had an immense impact on later collectors and editors (see also, Andersen 1994 and Brown 1997). In what follows I shall first give an outline of the earliest extensively documented singing community in the Anglo-Scottish ballad tradition, and then present a detailed analysis of two versions of the same ballad story (“The Cruel Mother”) taken down on the same day in 1825 from two singers from the same Scottish village. -

Learning Lineage and the Problem of Authenticity in Ozark Folk Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music Kevin Lyle Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tharp, Kevin Lyle, "Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1829. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEARNING LINEAGE AND THE PROBLEM OF AUTHENTICITY IN OZARK FOLK MUSIC A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi by KEVIN L. THARP May 2020 Copyright Kevin L. Tharp 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Thorough examination of the existing research and the content of ballad and folk song collections reveals a lack of information regarding the methods by which folk musicians learn the music they perform. The centuries-old practice of folk song and ballad performance is well- documented. Many Child ballads and other folk songs have been passed down through the generations. Oral tradition is the principal method of transmission in Ozark folk music. The variants this method produces are considered evidence of authenticity. Although alteration is a distinguishing characteristic of songs passed down in the oral tradition, many ballad variants have persisted in the folk record for great lengths of time without being altered beyond recognition. -

English Folk Ballads Collected By

Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University English Folk Ballads Collected by Cecil James Sharp < 79 http://jpnu.pu.if.ua Vol. 1, No. 2,3 (2014), 79-85 UDC 821.111:82-144(292.77) doi: 10.15330/jpnu.1.2,3.79-85 ENGLISH FOLK BALLADS COLLECTED BY CECIL JAMES SHARP IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS: GENESIS, TRANSFORMATION AND UKRAINIAN PARALLELS OKSANA KARBASHEVSKA Abstract. The purpose of this research, presented at the Conference sectional meeting, is to trace peculiarities of transformation of British folk medieval ballads, which were brought to the Southern Appalachians in the east of the USA by British immigrants at the end of the XVIIIth – beginning of the XIXth century and retained by their descendants, through analyzing certain texts on the levels of motifs, dramatis personae, composition, style and artistic means, as well as to outline relevant Ukrainian parallels. The analysis of such ballads, plot types and epic songs was carried out: 1) British № 10: “The Twa Sisters” (21 variants); American “The Two Sisters”(5 variants) and Ukrainian plot type I – C-5: “the elder sister drowns the younger one because of envy and jealousy” (8 variants); 2) British № 26: The Three Ravens” (2), “The Twa Corbies” (2); American “The Three Ravens” (1), “The Two Crows”(1) and Ukrainian epic songs with the motif of lonely death of a Cossack warrior on the steppe (4). In our study British traditional ballads are classified according to the grouping worked out by the American scholar Francis Child (305 numbers), Ukrainian folk ballads – the plot-thematic catalogue developed by the Ukrainian folklorist Оleksiy Dey (here 288 plots are divided into 3 spheres, cycles and plot types). -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

Jean Thomas' American Folk Song Festival : British Balladry in Eastern Kentucky

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 4-1978 Jean Thomas' American Folk Song Festival : British balladry in Eastern Kentucky. Marshall A. Portnoy University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Portnoy, Marshall A., "Jean Thomas' American Folk Song Festival : British balladry in Eastern Kentucky." (1978). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3361. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3361 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEAN THOMAS' AfiERICAN FOLK SONG FESTIVAL: ''. BRITISH BALLADRY IN EASTERN KENTUCKY ·By . Marshall A. Portnoy '" B.A., Yale University, 1966 M.S., Southern Connecticut State College, 1967 B. Mus., The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1971 Diploma of Hazzan, School of Sacred Music of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Music History Division of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky April 1978 © 1978 MARSHALL ALAN PORTNOY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED JEAN THOMAS' AMERICAN FOLK SONG FESTIVAL: BRITISH BALLADRY IN EASTERN KENTUCKY By Marshall A. -

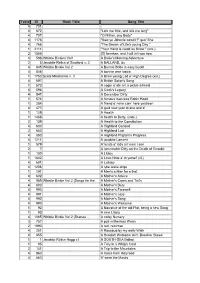

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Tradition Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography

Tradition label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography The Tradition Label was established in New York City in 1956 by Pat Clancy (of the Clancy Brothers) and Diane Hamilton. The label recorded folk and blues music. The label was independent and active from 1956 until about 1961. Kenny Goldstein was the producer for the label during the early years. During 1960 and 1961, Charlie Rothschild took over the business side of the company. Clancy sold the company to Bernard Solomon at Everest Records in 1966. Everest started issuing albums on the label in 1967 and continued until 1974 using recordings from the original Tradition label and Vee Jay/Horizon. Samplers TSP 1 - TraditionFolk Sampler - Various Artists [1957] Birds Courtship - Ed McCurdy/O’Donnell Aboo - Tommy Makem and Clancy Brothers/John Henry - Etta Baker/Hearse Song - Colyn Davies/Rodenos - El Nino De Ronda/Johnny’s Gone to Hilo - Paul Clayton/Dark as a Dungeon - Glenn Yarbrough and Fred Hellerman//Johnny lad - Ewan MacColl/Ha-Na-Ava Ba-Ba-Not - Hillel and Aviva/I Was Born about 10,000 Years Ago - Oscar Brand and Fred Hellerman/Keel Row - Ilsa Cameron/Fairy Boy - Uilleann Pipes, Seamus Ennis/Gambling Suitor - Jean Ritchie and Paul Clayton/Spiritual Trilogy: Oh Freedom, Come and Go with Me, I’m On My Way - Odetta TSP 2 - The Folk Song Tradition - Various Artists [1960] South Australia - A.L. Lloyd And Ewan Maccoll/Lulle Lullay - John Jacob Niles/Whiskey You're The Devil - Liam Clancy And The Clancy Brothers/I Loved A Lass - Ewan MacColl/Carraig Donn - Mary O'Hara/Rosie - Prisoners Of Mississippi State Pen//Sail Away Ladies - Odetta/Ain't No More Cane On This Brazis - Alan Lomax, Collector/Railroad Bill - Mrs. -

Controlling Women: "Reading Gender in the Ballads Scottish Women Sang" Author(S): Lynn Wollstadt Source: Western Folklore, Vol

Controlling Women: "Reading Gender in the Ballads Scottish Women Sang" Author(s): Lynn Wollstadt Source: Western Folklore, Vol. 61, No. 3/4 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 295-317 Published by: Western States Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1500424 . Accessed: 09/04/2013 10:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Western States Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Western Folklore. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.107.8.10 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 10:20:12 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ControllingWomen ReadingGender in theBallads ScottishWomen Sang LYNN WOLLSTADT The Scottishballad traditionhas alwaysbeen a traditionof both sexes; since ballads startedto be collected in the eighteenthcentury, at least, both men and women have learned and passed on these traditional songs.1According to the recordingsmade of traditionalsingers by the School of ScottishStudies at the Universityof Edinburgh,however, men and women do not necessarilysing the same songs.The ten songsin the School's sound archives most often recorded from female singers between 1951 and 1997, for example, have only two titlesin common withthe ten songs mostoften recorded frommen.2 Analysis of the spe- cificballad narrativesthat were most popular among female singersin twentieth-centuryScotland suggestscertain buried themes that may underlie that popularity;these particularthemes may have appealed more than othersto manywomen singers.