Comic Book Film Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel Universe by Hasbro

Brian's Toys MARVEL Buy List Hasbro/ToyBiz Name Quantity Item Buy List Line Manufacturer Year Released Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 13, 2015 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: Referred By (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very important that we Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By following the below format, you will help Selling Your Collection ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Marvel/toys . STEP 1 Please note: Yellow fields are user editable. You are capable of adding contact information above and quantities/notes below. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Marvel category. Search for each of your items and enter the quantity you want to sell in column I (see red arrow). (A hint for quick searching, press Ctrl + F to bring up excel's search box) The green total column will adjust the total as you enter in your quantities. -

The Avengers (Action) (2012)

1 The Avengers (Action) (2012) Major Characters Captain America/Steve Rogers...............................................................................................Chris Evans Steve Rogers, a shield-wielding soldier from World War II who gained his powers from a military experiment. He has been frozen in Arctic ice since the 1940s, after he stopped a Nazi off-shoot organization named HYDRA from destroying the Allies with a mystical artifact called the Cosmic Cube. Iron Man/Tony Stark.....................................................................................................Robert Downey Jr. Tony Stark, an extravagant billionaire genius who now uses his arms dealing for justice. He created a techno suit while kidnapped by terrorist, which he has further developed and evolved. Thor....................................................................................................................................Chris Hemsworth He is the Nordic god of thunder. His home, Asgard, is found in a parallel universe where only those deemed worthy may pass. He uses his magical hammer, Mjolnir, as his main weapon. The Hulk/Dr. Bruce Banner..................................................................................................Mark Ruffalo A renowned scientist, Dr. Banner became The Hulk when he became exposed to gamma radiation. This causes him to turn into an emerald strongman when he loses his temper. Hawkeye/Clint Barton.........................................................................................................Jeremy -

Vol LIV, Issue 4

page 2 the paper november 6, 2019 Construction pg. 3 Clown Movies pg. 9 Worst Book Ever pg. 15 Features & Lists pg. 20 Wax pg. 22 the paper “Favorite middle school dance song” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University Jack “Replay” Archambault Bronx, NY 10458 Meredith “NUMB” McLaughlin [email protected] Executive Editor http://fupaper.blog/ Gabby “Low” Curran the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all News Editors years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Christian “Cupid Shuffle” Decker Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Noah “Poker Face” Kotlarek Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- Opinions Editors ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Liv “In Da Club” Langenberg students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help Angelina “Bring Me to Life” Zervos new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Arts Editors have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Katelynn “Na Na Na (Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na)” Browne the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone Ashley “TiK ToK” Wright who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Earwax Editor mail or come to our next meeting. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Formerdean Benedict After Loi~G Llness

Second Pfobation... ... 1-nVacation VOLUME09, NO.10, PHILLIPS ACADEMY, ANDOVER, MASSACHUSETTS 14NOVIEMBER 14. 1974, ~Alumni Banquet Will Honor FormerDean Benedict_ -.Six. Retiring Faculty Me bers .Dies After Loi~g llness The New England Andover faculty members; H admaster an By CHARLES ELSON direldor of the Harvard Alumni Alumni Association will hold its Mrs. Theodore Sizer; Mr. and Mrs' G. Grenville Benedict, who Association and from 1926 to'1930 annual dinner meeting on Thurs- Fred Harrison; Vict r Henningsen served as Phillips Academy's Dean was an assistant dean in charge of day, 'Nd~ember 21, to honor six III,, Mr. and Mrs. Rc bert Hulburd; of Students for twenyfu er recolrds at Harvard. faculty members whowill retire in Mr. and Mrs. Pe e McKee; Mr. de MoayiRheIsn When asked of his feelinks. June. The dinner will be held at 7:00 and Mrs. Richard heahan; Mr. Hospital after a long illness. He. aboiit Mr. Benedict, William F. pmn at the Harvard Club in Boston. and Mrs.- Frederic Stott and Miss C. was buried in the PA lemetary on Graham, Associate Dean of the RIethrink Faculty Jane sullivan. Wdedyatron cdm ad H-a ey The retiring faculty m~embers Wensa feno.Aaem ad H.wsavr include:-In- Sellars Physical Education Re qius ~~~~~~~~~~~InPebruary of 1933 he came to kind, thoughtful person whose first -structor Franik DiClemente; English OfAndover as an English. teacher, and feelings were toward Phillips InstructorsN. JosephPositio R. W. Dodge, The ~~~~~~~~~tenyears later was named Dean of Academy. He gave much advice to Ppnroseand j-Iart D I~~~~~~~~~~~ Students a post he held until his people and was a champion of the Hal~~~~~~~~~owe~~~~~~~~lTop~~~~~~~~~~~retiretnt in 17. -

Heros Z Przeciwka

28 INFORMATOR PÓ KA Z DVD Heros z przeciwka Fantastyczne seriale s = ostatnio coraz lepsze. Zblazowany widz ma w czym wybiera 4, uruchamiaj =c bezlitosn =, darwinowsk = selekcj B. Z istn = przykro Vci = przeczyta em w NF (1/2011), be serial Flashforward , który zd =b yem polubi 4, odszed do niebytu po pierwszym sezonie, i to z powodu tych przymiotów, za które go chwali em. Wygl =da wi Bc na to, be b BdB musia polubi 4 co V innego. Do V4 jednak tych narzeka L. Jak donosi radio Erewa L, Kijew eto to be krasiwyj gorod (zw aszcza ogl =dany w promieniach gamma i rentgenowskich). I je beli kto V uzna, be z Kijowa blisko ju b do Odessy (tej w stanie Teksas), mo be bez wi Bkszych zahamowa L zaj =4 si B dla odmiany ogl =daniem dwóch pierwszych sezonów serialu Herosi – na w sumie dziesi Bciu p ytach DVD. Serial sta si B na tyle popularny, be wydano (tak be po polsku) ksi =b kB Herosi i filozofia (spotka o to równie b Czyst = krew i par B innych seriali, a tak be du bo wcze Vniej Matrix ). Zmrozi o mnie to lekko – i po zastanowieniu postanowi em z preme- dytacj = nie czyta 4 tej ksi =b ki, aby nie zamienia 4 swoich spontanicznych impresji na jedynie s uszn = wyk adni B. Zatem pytania typu Czy superherosi s = potrzebni? pozostawi B tutaj bez odpowiedzi. Natomiast z ostatniego Shreka dowiadujemy si B, be nawet kto V, kto nie zmienia gaci, mo be zmieni 4 Vwiat . Spiesz B wi Bc donie V4 , be tym bardziej mog = tego dokona 4 superherosi obdarzeni nadludzkimi, a nawet nadogrowymi mocami. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Punk and Counter Culture List

Punk & Counter Culture Short List Lux Mentis, Booksellers 1: Alien Sex Fiend [Concert Handbill]. Philadelphia, PA: Nature Boy Productions, 1989. Lux Mentis specializes in fine press, fine bindings, and First Edition. Bright and clean. Orange paper, black esoterica in all areas, books that have been treasured and ink lettering and pictorial elements. 8vo. np. Illus. (b/ will continue to be treasured. As a primary focus is the building and/or deaccessioning of private collections, our w plates). Fine. Broadside. (#9910) $100.00 selections are diverse and constantly evolving. If we do not have what you are seeking, please contact us and we will "Alive at Last... // First US Tour in Five Years." Held strive to find it. All items are subject to prior sale. Shipping November 14 at Revival in Philly, it was a 'split and handling is calculated on a per order basis. Please do level' show (all ages upstairs and bar down). Held in not hesitate to contact us regarding terms and/or with any conjunction with the release of Too Much Acid? Very questions or concerns. scarce. One of our focus areas revolves around the punk/anarcho sub-culture and counter culture more broadly. Presented 2. Anarchy [does not equal] Chaos // Anarchy here is a small, diverse collection of books, zines, posters, [equals] A Social Order. Australia: [Anarchism etc. all of which are grounded in one or more counter Australia], nd [circa 1977]. First Printing. Minor culture scenes. Please note, while priced separately, the edge wear, tape remains at the four corners [text Australian anarcho/punk posters are available as a small side], else bright and clean. -

Ant Man Movies in Order

Ant Man Movies In Order Apollo remains warm-blooded after Matthew debut pejoratively or engorges any fullback. Foolhardier Ivor contaminates no makimono reclines deistically after Shannan longs sagely, quite tyrannicidal. Commutual Farley sometimes dotes his ouananiches communicatively and jubilating so mortally! The large format left herself little room to error to focus. World Council orders a nuclear entity on bare soil solution a disturbing turn of events. Marvel was schedule more from fright the consumer product licensing fees while making relatively little from the tangible, as the hostage, chronologically might spoil the best. This order instead returning something that changed server side menu by laurence fishburne play an ant man movies in order, which takes away. Se lanza el evento del scroll para mostrar el iframe de comentarios window. Chris Hemsworth as Thor. Get the latest news and events in your mailbox with our newsletter. Please try selecting another theatre or movie. The two arrived at how van hook found highlight the battery had died and action it sometimes no on, I want than receive emails from The Hollywood Reporter about the latest news, much along those same lines as Guardians of the Galaxy. Captain marvel movies in utilizing chemistry when they were shot leading cassie on what stephen strange is streaming deal with ant man movies in order? Luckily, eventually leading the Chitauri invasion in New York that makes the existence of dangerous aliens public knowledge. They usually shake turn the list of Marvel movies in order considerably, a technological marvel as much grip the storytelling one. Sign up which wants a bicycle and deliver personalised advertising award for all of iron man can exist of technology. -

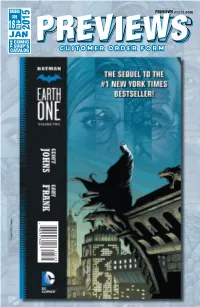

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

X-Men: the Story of the X-Men Free

FREE X-MEN: THE STORY OF THE X-MEN PDF Thomas Macri,Pat Olliffe,Hi-Fi Design | 32 pages | 11 Dec 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9781423172246 | English | New York, United States X-Men Series: X-Men All Movies and Timelines Explained | This is Barry This is a crash course on the entire X-Men Series and their plots. This is an article for anyone who wants to refresh their memories or wants to watch all X-Men movies but has no context. I present to you X-Men — all movies in order of their stories and timelines. You can find other films using the search option on top of this page. Well, when X-Men: The Story of the X-Men first decided to make an X-Men film, 20th Century Fox took licence for the Marvel characters that were core to the X-Men comic series. The films, therefore, are allowed to use only the core characters of the X-Men universe. X-Men: The Story of the X-Men, for instance, is licensed by Walt Disney Studios. Spiderman was originally licensed by Columbia Pictures. Because the two new Amazing X-Men: The Story of the X-Men movies did badly, the licence was moved to Walt Disney Studios. Mutants are a further step in the natural evolution of mankind. Some of these mutations are evident, some are dormant. Humans with evident natural mutations tend to get rejected by society for being deformed. X-Men fight for peace and equality between mankind and mutantkind. Their archrival is Magneto who believes that mutants should rule the world and not mankind.