THE STORY of an ENGLISH SAINT's CULT: an ANALYSIS of the INFLUENCE of ST ÆTHELTHRYTH of ELY, C.670

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Mission As Translation with Reference to Michael Polanyi's

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Haney, Richard L. (2014) Mapping mission as translation with reference to Michael Polanyi’s heuristic philosophy. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13666/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

St. Edward the Confessor Feast: October 13

St. Edward the Confessor Feast: October 13 Facts Feast Day: October 13 Edward the Confessor was the son of King Ethelred III and his Norman wife, Emma, daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy. He was born at Islip, England, and sent to Normandy with his mother in the year 1013 when the Danes under Sweyn and his son Canute invaded England. Canute remained in England and the year after Ethelred's death in 1016, married Emma, who had returned to England, and became King of England. Edward remained in Normandy, was brought up a Norman, and in 1042, on the death of his half-brother, Hardicanute, son of Canute and Emma, and largely through the support of the powerful Earl Godwin, he was acclaimed king of England. In 1044, he married Godwin's daughter Edith. His reign was a peaceful one characterized by his good rule and remission of odious taxes, but also by the struggle, partly caused by his natural inclination to favor the Normans, between Godwin and his Saxon supporters and the Norman barons, including Robert of Jumieges, whom Edward had brought with him when he returned to England and whom he named Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051. In the same year, Edward banished Godwin, who took refuge in Flanders but returned the following year with a fleet ready to lead a rebellion. Armed revolt was avoided when the two men met and settled their differences; among them was the Archbishop of Canterbury, which was resolved when Edward replaced Robert with Stigand, and Robert returned to Normandy. -

Church of Saint Edward the Confessor

Mike Greene 740-345-3510 Village Tim Hughes Realtor 51 North Third Tower • Newark Flower Basket 1090 River Road VILLAGE FLOWER Granville Business Proudly serving the area for over 37 years! BASKET & GARDENS Church of Saint Edward Technologies, Inc. GRANVILLE, OHIO 587-3439 328-9051 COPIERS • PRINTERS • FAX 1290 HEBRON RD., Kelly Parker – Professional Full Home of Service REALTOR® HEATH, OH Ye Olde 238 E. Broadway, Jeep Mill (1 mile South of Indian Mound Mall) Since 1914 David Hughes, OCNT Granville, OH the Confessor 11324 Mt. Vernon Rd., Utica FAMILY OWNED MEMBERS 740-892-3921 740-344-5493 Cell 740-334-9777 OVER 37 YEARS 522-3153 OF PARISH www.velveticecream.com “We Share Your Passion for Garden Excellence” KellyParkerHome.com Serving Granville & A Place To Call Om Newark for Leigh Brennan, RYT • 740-404-9190 • aplacetocallom.com Grand pastor: DeaCon: over 29 years. Mon., 6:30pm – Power Flow with Weights; Monuments SGR AUL NKE EV R OHN ARBOUR 345-2086 Tues., 9:30am – Flow Yoga; Wed., 7:45pm – Flow Yoga; 1600 East Main St. M . P P. E R . M . J B Residential & Commercial Newark, Ohio 43055 Visa & MasterCard accepted Fri., 9:00am – Flow Yoga; Sat., 11:45am – Power Flow Yoga; www.bigorefuse.com Sun., 7:30pm – Gentle Yoga 345-8772 1190 E. Main Street, Newark, OH 43055 740-349-8686 assisting Clergy AUTOMOTIVE PAINTLESS DENT REMOVAL FR. RONNIE BOCCALI, P.I.M.E. Downey’s Carpet Care • 22 Years Experience • Hail Damage • Body Line Dents FR. JAY HARRINGTON, O.P. of Granville • Crease Dents • Door Dings 587-4258 Bag & Bulk Mulch – Plants – Stone – Topsoil ERIC CLAEYS 740-404-5508 • Motorcycles 2135 West Main, Newark • www.hopetimber.com 462 S. -

Acknowledgements There Are a Number Ofpeople Whose Assistance

Acknowledgements There are a number ofpeople whose assistance and encouragement I must acknowledge with the sincerest gratitude and thanks: Professor C. Abbott Conway, McGill University provided me with guidance and encouragement over the past year and was exceedingly generous with his time, advice, and support regarding scholarship and career direction; he also taught me the true importance of primary sources. Professor Dorothy A. Bray, McGill University, for a gentle and finn guiding hand during my time at McGill, and for telling me when to stop reading and start writing. Ruth Wehlau, PhD. (T('ronto) whose work provided the basis for so much of my own. My parents and my parents-in law: Victor and Jacqueline Solomon and Robert and Esther Luchinger whose material support allowed me to invest the time to devote myself to my studies. Liisa Stephenson whose friendship helped to keep me on an even keel through the difficult stages ofthe creative process. Jason Polley whose editorial advice was of timely assistance. This work and all else of value that I ever do I dedicate to my blessed and beloved wife Martina. John-Christian Solomon M.A. Thesis - Abstract Department of English McGill University August 2002 Thesis Title: Healdeo Trywa Wel: The English Christ Abstract: An exan1ination of extant historical and literary evidence for the purpose of questioning the standard paradigm of the "Germanization of Christianity". While the melding and inclusion of both Mediterranean and Teutonic elements in Anglo-Saxon poetry has been the subject of extensive research, until relatively recently, scholars have attributed this dynamic largely to a central manipulation of the Christian message by the Roman church with a view towards making it compatible with the societal mores of the (relatively) newly convt..rted Northern Europeans. -

Anglican Church of Australia

ANGLICAN CHURCH OF AUSTRALIA Diocese of Willochra Prayer Diary December 2020 Page 1 of 32 DAY 1 Diocese of Willochra: • The Bishop John Stead (Jan); • Assistant Bishop and Vicar General Chris McLeod (Susan); • Chancellor of the Diocese of Willochra, Nicholas Iles (Jenny); • Chaplain to the Bishop, The Rev’d Anne Ford (Michael); • The Dean of the Cathedral Church of Sts Peter and Paul, Dean-elect Mark Hawkes (Fiona) • The Cathedral Chapter, The Bishop John Stead (Jan), Archdeacons – the Ven Gael Johannsen (George), the Ven Heather Kirwan, the Ven Andrew Lang (Louise); Canons – the Rev’d Canon Ali Wurm, the Rev’d Canon John Fowler, Canon Michael Ford (Anne), Canon Mary Woollacott; Cathedral Wardens - Pauline Matthews and Jean Housley • The Archdeacons, The Ven Heather Kirwan – Eyre and The Ven Andrew Lang (Louise) - Wakefield Diocese of Adelaide: St Frances, Trinity College, Gawler: Dave MacGillivray (Beth) Diocese of The Murray: Bishop Keith Dalby (Alice) In the Anglican Church of Australia: The Anglican Church of Australia; Primate, Archbishop Geoff Smith (Lynn); General Secretary, Anne Hywood (Peter); General Synod and Standing Committee In the Partner Diocese of Mandalay: Bishop David Nyi Nyi Naing (Mary), Rev’d John Suan and the Diocesan and Cathedral Staff Worldwide Anglican Cycle of Prayer: • Diocese of Seoul (Korea): Bishop Peter Lee • Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada): Bishop Geoffrey Peddle Page 2 of 32 DAY 2 Diocese of Willochra: • The Bishop John Stead (Jan); • The Rural Deans, The Rev’d Anne Ford (Michael) -

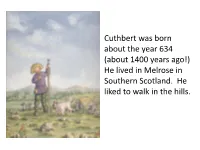

St Cuthbert Story

Cuthbert was born about the year 634 (about 1400 years ago!) He lived in Melrose in Southern Scotland. He liked to walk in the hills. One night, when he was helping to look after sheep he thought he saw angels taking a soul to heaven. A few days later he found out Saint Aidan had died. Cuthbert decided to become a monk. He became a monk at the monastery in Melrose where he met Boisil, the prior of the monastery. Boisil taught Cuthbert for 6 years. Before Boisil died, he told Cuthbert he would be a Bishop one day. Cuthbert liked to visit lonely farms and villages. Crowds of people came to visit him. He lived at Melrose monastery for 13 years. Cuthbert was sent to be Prior of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert taught the monks the new Roman church rules. Some of the monks did not like the new rules and Cuthbert had to be very patient with them. After 12 years, Cuthbert went to live on a quiet island 7 miles away from Lindisfarne. Cuthbert lived on this small island for 3 years. He grew barley and vegetables and his monks dug a well and built a guest house for visitors. The King asked Cuthbert to be Bishop of Hexham. Cuthbert didn’t want to but he still remembered what Boisil had said. Cuthbert did not want to be Bishop of Hexham but agreed to be Bishop of Lindisfarne instead. He was very sad to have to leave his small island. Cuthbert was Bishop of Lindisfarne for 2 years. The people loved him. -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain. -

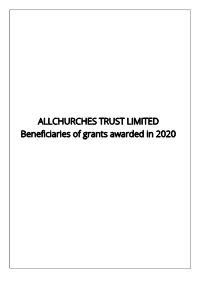

Allchurches Trust Beneficiaries 2020

ALLCHURCHES TRUST LIMITED Beneficiaries of grants awarded in 2020 1 During the year, the charity awarded grants for the following national projects: 2020 £000 Grants for national projects: 4Front Theatre, Worcester, Worcestershire 2 A Rocha UK, Southall, London 15 Archbishops' Council of the Church of England, London 2 Archbishops' Council, London 105 Betel UK, Birmingham 120 Cambridge Theological Federation, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire 2 Catholic Marriage Care Ltd, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 16 Christian Education t/a RE Today Services, Birmingham, West Midlands 280 Church Pastoral Aid Society (CPAS), Coventry, West Midlands 7 Counties (formerly Counties Evangelistic Work), Westbury, Wiltshire 3 Cross Rhythms, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 3 Fischy Music, Edinburgh 4 Fusion, Loughborough, Leicestershire 83 Gregory Centre for Church Multiplication, London 350 Home for Good, London 1 HOPE Together, Rugby, Warwickshire 17 Innervation Trust Limited, Hanley Swan, Worcestershire 10 Keswick Ministries, Keswick, Cumbria 9 Kintsugi Hope, Boreham, Essex 10 Linking Lives UK, Earley, Berkshire 10 Methodist Homes, Derby, Derbyshire 4 Northamptonshire Association of Youth Clubs (NAYC), Northampton, Northamptonshire 6 Plunkett Foundation, Woodstock, Oxfordshire 203 Pregnancy Centres Network, Winchester, Hampshire 7 Relational Hub, Littlehampton, West Sussex 120 Restored, Teddington, Middlesex 8 Safe Families for Children, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 280 Safe Families, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Tyne and Wear 8 Sandford St Martin (Church of England) Trust, -

The Lives of the Saints

Itl 1 i ill 11 11 i 11 i I 'M^iii' I III! II lr|i^ P !| ilP i'l ill ,;''ljjJ!j|i|i !iF^"'""'""'!!!|| i! illlll!lii!liiy^ iiiiiiiiiiHi '^'''liiiiiiiiilii ;ili! liliiillliili ii- :^ I mmm(i. MwMwk: llliil! ""'''"'"'''^'iiiiHiiiiiliiiiiiiiiiiiii !lj!il!|iilil!i|!i!ll]!; 111 !|!|i!l';;ii! ii!iiiiiiiiiiilllj|||i|jljjjijl I ili!i||liliii!i!il;.ii: i'll III ''''''llllllllilll III "'""llllllll!!lll!lllii!i I i i ,,„, ill 111 ! !!ii! : III iiii CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY l,wj Cornell Unrversity Library BR 1710.B25 1898 V.5 Lives ot the saints. Ili'lll I 3' 1924 026 082 572 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082572 THE ilibes? of tlje t)atnt0 REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE FIFTH THE ILities of tlje g)amt6 BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE FIFTH LONDON JOHN C. NFMMO &-• NEW YORK . LONGMANS, GREEN. CO. MDCCCXCVIll / , >1< ^-Hi-^^'^ -^ / :S'^6 <d -^ ^' Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> CO. At the Ballantyne Press *- -»5< im CONTENTS PAGE Bernardine . 309 SS. Achilles and comp. 158 Boniface of Tarsus . 191 B. Alcuin 263 Boniface IV., Pope . 345 S. Aldhelm .... 346 Brendan of Clonfert 217 „ Alexander I., Pope . -

History and Antiquities of Stratford-Upon-Avon

IL LINO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Brittle Books Project, 2009. UNIVERSrryOF ILLINOIS-URBANA ' 3 0112 079790793 C) c)J U0 CI 0F 622-5 CV157 111STORY & ANTIQUITIES STR4TF RkDi U]PO~A I1 ONA"r III c iI1Pir . i r M t a r HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF 5TJRATFORDJPONAVON: fO MPRISI N C A DESCRIPTION OF THlE COLLEGIATE CHURCH,7 THE LIFE OF SJL4KSPEAJRJ, AN Copies of several Documents relating to him anti his Pamniy never before printed; WITH A 13IOGt4PII1C4L SKETCH OF OTHER -V MJNENT CILIRACT2PS , Natives of, or who have resided in STRITFORD, To which, is added, a particular Account of THE- JUBILEE, Celebrated at Stratford, in Honour of our immortal Bard, BYT R. B. WIIELER. 0 gratum Musis, 0 nornen. amabile Plwcbo, Qtam sociarn adsciscant, Minicius atque Meles. Ac tibi, cara hospes, si mens divinior, et te Ignea SiKSPEARI muss ciere queat; Siste gradum; crebroquc oculos circum undique liectas, Pierii lae inontes, hec tOb Pindus erit. &ttatfouYon5ivbon: PRTNTED AND~ SOLD BY J. WARD; SOLD ALSO BYVLONGISAN AND CO.PATERNOSTERa ROW, LONDON'S WILKS AND CO. BIRIMINGHAM, AN!) BY MOST OTHER BOOKSELLERS IN TOWN AND COUNTIRY W2,2. Z3 cws;-7 PREFACE., FIE want of a work in some degree sifilar to the. res sent undertaking eatcouraged the publication of the follow4 ilig sheets, the'offspring oft afew leisure hours; and it is hoped that the world will, on an impartial perusal, make aflowanees for the imperfections, by reflecting as well upon the inexperieace of the Jiuvenile author, as that they were originally collected for"his own private information. -

The Venerable Bede a Celebration

The Venerable Bede A Celebration Monday 25 May 2020 5.15 p.m. The Venerable Bede Bede served in the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow for all his life, and died in Jarrow in 735 aged about 62. In 1020, his body was brought to Durham to be placed with the body of St Cuthbert. Bede’s body was brought to its final resting place in the Galilee Chapel in 1370. Introit Christ is the Morning Star Christ is the Morning Star who when the night of this world is past brings to his saints the promise of the light of life and opens everlasting day. Alleluia. The Venerable Bede Richard Lloyd The Dean welcomes the people Hymn We sing to God in praise of Bede (tune NEH 431) We sing to God in praise of Bede, The prince of scholars in his age, Christ’s servant, lover of God’s word, Once monk of Jarrow, priest and sage. For his example we give thanks, His zeal to learn, his skill to write; Like him we long to know God’s ways And in God’s word drink with delight. Grant us, good Lord, one day to come To you, all wisdom’s fountainhead, With Bede to stand before your face, Our Saviour, living from the dead. Teach us, O Lord, like Bede to pray, To make the word of God our joy, Exult in music, song and art, In worship all your gifts employ. O Christ, our glorious Morning Star, Come with the passing of the night, Bring to your saints th’eternal day, The promise of your life and light.