An Account of Research Being Done in ITE. Cambridge, NERC/Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, 116-117

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dutch Elm Disease Pathogen Transmission by the Banded Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus Schevyrewi

For. Path. 43 (2013) 232–237 doi: 10.1111/efp.12023 © 2013 Blackwell Verlag GmbH Dutch elm disease pathogen transmission by the banded elm bark beetle Scolytus schevyrewi By W. R. Jacobi1,3, R. D. Koski1 and J. F. Negron2 1Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; 2U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest Research Station, Fort Collins, CO USA; 3E-mail: [email protected] (for correspondence) Summary Dutch Elm Disease (DED) is a vascular wilt disease of Ulmus species (elms) incited in North America primarily by the exotic fungus Ophios- toma novo-ulmi. The pathogen is transmitted via root grafts and elm bark beetle vectors, including the native North American elm bark beetle, Hylurgopinus rufipes and the exotic smaller European elm bark beetle, Scolytus multistriatus. The banded elm bark beetle, Scolytus schevyrewi, is an exotic Asian bark beetle that is now apparently the dominant elm bark beetle in the Rocky Mountain region of the USA. It is not known if S. schevyrewi will have an equivalent vector competence or if management recommendations need to be updated. Thus the study objectives were to: (i) determine the type and size of wounds made by adult S. schevyrewi on branches of Ulmus americana and (ii) determine if adult S. schevyrewi can transfer the pathogen to American elms during maturation feeding. To determine the DED vectoring capability of S. schevyrewi, newly emerged adults were infested with spores of Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and then placed with either in-vivo or in-vitro branches of American elm trees. -

Published Version

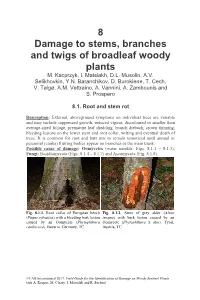

8 Damage to stems, branches and twigs of broadleaf woody plants M. Kacprzyk, I. Matsiakh, D.L. Musolin, A.V. Selikhovkin, Y.N. Baranchikov, D. Burokiene, T. Cech, V. Talgø, A.M. Vettraino, A. Vannini, A. Zambounis and S. Prospero 8.1. Root and stem rot Description: External, aboveground symptoms on individual trees are variable and may include suppressed growth, reduced vigour, discoloured or smaller than average-sized foliage, premature leaf shedding, branch dieback, crown thinning, bleeding lesions on the lower stem and root collar, wilting and eventual death of trees. It is common for root and butt rots to remain unnoticed until annual or perennial (conks) fruiting bodies appear on branches or the main trunk. Possible cause of damage: Oomycetes (water moulds: Figs. 8.1.1 – 8.1.3); Fungi: Basidiomycota (Figs. 8.1.4 – 8.1.7) and Ascomycota (Fig. 8.1.8). Fig. 8.1.1. Root collar of European beech Fig. 8.1.2. Stem of grey alder (Alnus (Fagus sylvatica) with a bleeding bark lesion incana) with bark lesion caused by an caused by an Oomycete (Phytophthora Oomycete (Phytophthora x alni). Tyrol, cambivora). Bavaria, Germany, TC. Austria, TC. ©CAB International 2017. Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (eds A. Roques, M. Cleary, I. Matsiakh and R. Eschen) Damage to stems, branches and twigs of broadleaf woody plants 105 Fig. 8.1.3. European chestnut (Castanea Fig. 8.1.4. Collar of European beech sativa) showing bark lesion caused by an (Fagus sylvatica) with fungal fruiting Oomycete (Phytophthora cinnamomi). bodies (Polyporus squamosus). -

Vectors of Dutch Elm Disease in Northern Europe

insects Article Vectors of Dutch Elm Disease in Northern Europe Liina Jürisoo 1,*, Ilmar Süda 2, Ahto Agan 1 and Rein Drenkhan 1 1 Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Fr.R. Kreutzwaldi 5, 51006 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (R.D.) 2 Ilmar Süda FIE, Rõõmu tee 12-5, 50705 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Dutch elm disease (DED) has been killing elms for more than a century in northern Europe; the trees’ health status has worsened substantially in recent decades. Elm bark beetles Scolytus spp. are vectors of DED. Our aim was to estimate the distribution range of elm bark beetles and to detect potential new vectors of DED agents in northern Europe. Beetles were caught with bottle traps and manually. Then DNA from each specimen was extracted and analysed by the third generation sequencing method. DED agents were detected on the following bark beetles for Europe: Scolytus scolytus,S. triarmatus, S. multistriatus, S. laevis, and on new vectors: Xyleborus dispar and Xyleborinus saxesenii. The spread of Scolytus triarmatus, S. multistriatus and Xyleborinus saxesenii has been remarkable for the last two decades, and S. triarmatus and X. saxesenii are relatively recent newcomers in the northern Baltics. The problem is that the more vectoring beetles there are, the faster spread of Dutch elm disease from tree to tree. Abstract: Potential Dutch elm disease vector beetle species were caught with pheromone bottle traps and handpicked in 2019: in total, seven species and 261 specimens were collected. -

Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs Volume 11 a Catalog of Scolytidae and Platypodidae Article 5 (Coleoptera), Part 1: Bibliography

Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs Volume 11 A Catalog of Scolytidae and Platypodidae Article 5 (Coleoptera), Part 1: Bibliography 1-1-1987 I–L Stephen L. Wood Life Science Museum and Department of Zoology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602 Donald E. Bright Jr. Biosystematics Research Centre, Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 51A 0C6 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Stephen L. and Bright, Donald E. Jr. (1987) "I–L," Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs: Vol. 11 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm/vol11/iss1/5 This Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 280 Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs No. 11 lABLOKOFF, ARHl'R KHINDZOHIAN. 1953. Les plantations in stem pests nidus]. Lesovedenie 1975(6):27—36. de pin sylvestre et la migration des xylophages. (ec). Revue Forestiere Francaise 5(5):321-327. (ee ds). Ifju. G . P C Ferguson, and R. G Oderwald. 1977. IabloKOFF-KhnzoRIAN. S. M. 1961. Experiments in es- Pulping and papermaking properties of southern tablishing the genesis of the larva of Coleoptera of pine harvested from beetle-infested forests. Pages Armenia [In Russian]. Akademiia Nauk Armian- 164-176. TAPPI Forest Biology and Wood Chem- skoi SSR, Zoologicheski Institut. 266 p. -

Phoretic Mites and Nematode Associates of Scolytus Multistriatus and Scolytus Pygmaeus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in Austria

Agricultural and Forest Entomology (2005) 7, 169–177 Phoretic mites and nematode associates of Scolytus multistriatus and Scolytus pygmaeus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in Austria John C. Moser, Heino Konrad*, Thomas Kirisits* and Lynn K. Carta† USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, 2500 Shreveport Highway, Pineville, LA 71360, U.S.A., *Institute of Forest Entomology, Forest Pathology, and Forest Protection (IFFF), Department of Forest and Soil Sciences, BOKU – University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Hasenauerstrasse 38, A-1190 Vienna, Austria and yUSDA-ARS, Nematology Laboratory, Beltsville, MD 20705, U.S.A. Abstract 1 The species assemblages and abundance of phoretic mites and nematodes associated with the elm bark beetles, Scolytus multistriatus and Scolytus pygmaeus, were studied in Austria. 2 A total of 3922 individual mites were recorded from 144 adults of S. multi- striatus and 178 adults of S. pygmaeus. The species spectrum was identical and the relative abundance of mites was very similar for both species of scolytids. Nine mite species, Pyemotes scolyti, Pseudotarsonemoides eccoptogasteri, Trichouropoda bipilis, Tarsonemus crassus, Proctolaelaps eccoptogasteris, Proctolaelaps scolyti, Chelacheles michalskii,nr.Eueremaeussp. and Elattoma sp. were detected. Two of the nine species, nr. Eueremaeus sp. and Elattoma sp., are documented here as new associates of Scolytus spp. 3 Pyemotes scolyti was the most frequent mite species, and Ps. eccoptogasteri and T. bipilis were relatively common, whereas the other mites occurred occasion- ally or were rare. 4 The trophic roles of most of the mites associated with S. multistriatus and S. pygmaeus are poorly known, but they may include fungivores, parasitoids of bark beetle broods, predators of bark beetle broods and/or mites and/or nematodes. -

Research on Dutch Elm Disease in Europe

Forestry Commission ARCHIVE Cover Summary of the known positions of the Eurasian (EAN) and North American (NAN) races of the aggressive strain of Ceratocystis ulmi in Europe in 1981. Green, EAN race; red, NAN race. Based on identifications of the fungus in artificial culture from isolations made from over one thousand samples collected by Dr. C. M. Brasier (see pp. 96-104). The distribution of the non-aggressive strain of C. ulm iis not shown. FORESTRY COMMISSION BULLETIN No. 60 Research on Dutch elm disease in Europe PROCEEDINGS OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY RESEARCH SEMINAR, GUERNSEY, CHANNEL ISLANDS, 30th MARCH — 1st APRIL 1982 Edited by D. A. BURDEKIN, B.A., Dip. Ag. Sci., Chief Research Officer, Forestry Commission, Forest Research Station, Alice Holt Lodge, Wrecclesham, Farnham, Surrey, GU10 4LH, U.K. LONDON : HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE © Crown copyright 1983 First published 1983 ISBN 0 11 710153 2 Contents ruge INTRODUCTION D. A. Burdekin V DUTCH ELM DISEASE CONTROL 1. Dutch elm disease control campaign in Guernsey, G. F. Riley 1 Channel Islands, 1976-1981 2. Dutch elm disease control campaign in Jersey, G. Journeaux 5 Channel Islands, 1974-1982 3. Control of Dutch elm disease in Britain B. J. W. Greig and J. N. Gibbs 10 4. Dutch elm disease control in the Netherlands J. K. Water 17 5. Dutch elm disease in Denmark A. Yde-Andersen 19 6. Evaluation of the trap tree technique for the control D. P. O’Callaghan and 23 of Dutch elm disease in northwest England C. P. Fairhurst ENTOMOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF DUTCH ELM DISEASE 7. -

Aggregation Pheromone of the Almond Bark Beetle Scolytus Amygdali (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) S

Use of pheromones and other semiochemicals in integrated production IOBC wprs Bulletin Vol. 25(•) 2002 pp. •-• Aggregation pheromone of the almond bark beetle Scolytus amygdali (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) S. Ben-Yehuda, T. Tolasch,1 W. Francke,2 R. Gries,2 G. Gries,2 D. Dunkelblum and Z. Mendel Department of Entomology, ARO, The Volcani Center, Bet Dagan, 50250, Israel 1 Institute of Organic Chemistry, University of Hamburg, D-20146, Germany 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, V5A 1S6, Canada Abstract: The almond bark beetle (ABB), Scolytus amygdali (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), is a pest of stone fruits in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe. Adults feeding on buds cause most of the damage. Applications of non-selective insecticides, burning of dead trees and pruning slash are environmentally unsafe and are often ineffective for ABB control. Preliminary experiments with ABB colonizing branches indicated the existence of an aggregation pheromone, and prompted us to identify it. Volatiles emitted by female ABB boring into plum branches were collected on Porapak Q and eluted with hexane. GC-EAD analyses of volatile extracts, using female antennae as an electroan- tennographic detector, revealed four EAD-active candidate pheromone components, as follows: (3S,4S)-4-methyl-3-heptanol (SS-I), most abundant and EAD-active component; (3S,4S)-4-methyl-3- hexanol (SS-II); (5S,7S)-7-methyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[4,5]decane (III); and 7-methyl-1,6-dioxaspiro [4,5]dec-8-ene [IV], the first unsaturated spiroaketal found in insects. In field experiments (1994- 1998) using funnel traps baited with polyethylene pheromone dispensers, SS-I unlike SS-II was at- tractive by itself, while SS-I plus SS-II at a ratio of 2:1 was optimally attractive. -

Ecology & Management of Bark-Beetle Forest Pests

Some scolytid pests Some bark -beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans Dendroctonus micans Some scolytid pests Ecology and Management of Bark-Beetle Forest Pests 1. Dendroctonus micans 2. Ips typographus 3. Trypodendron spp. Jean-Claude Grégoire Biological Control and Spatial Ecology Lab 4. Scolytus multistriatus Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium 5. Scolytus scolytus [email protected] 6. Dendroctonus ponderosae Some bark -beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans Some bark -beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans Some bark -beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans 1 Some bark-beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans Some bark -beetle pests - Dendroctonus micans Some forest pests - Dendroctonus micans Some forest pests - Dendroctonus micans Some forest pests – Ips typographus Some forest pests – Ips typographus Ips typographus Kielder forest (43,000 ha in England + 50,000 ha in Lothian & Strathclyde : Border) and surrounding area: main concern. 200,000 ha of Sitka North Yorkshire : Ae Forest (40,000 ha). 9,000 ha Total Dumfries & Galloway: Sitka = 104,000 ha; Norway = 5,000 ha Kent: Ashford. 40- 50 sites, all of which with R. South Molton grandis (Devon). 1 site D micans infested zones Unattacked zones, survey planned 2 Some forest pests – Ips typographus Some forest pests – Ips typographus Some forest pests – Trypodendron spp. Trypodendron spp. Some forest pests – Trypodendron spp. Some forest pests – Scolytus spp. Some forest pests – Scolytus spp. Scolytus multistriatus; S. scolytus Insects Symptoms Fungi Scolytus multistriatus Ophiostoma ulmi, O. novo-ulmi Scolytus scolytus 3 Some forest pests – Scolytus spp. Some forest pests – Scolytus spp. Some forest pests – Scolytus spp. Scolytus multistriatus Scolytus scolytus Cycle Some forest pests – Dendroctonus ponderosae in British Columbia. Some forest pests – Dendroctonus ponderosae in British Columbia. -

Life History and Biology of the Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus Kashmirensis Schedl (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Infesting Ulmus Villosa in Kashmir

Open Journal of Forestry, 2015, 5, 443-453 Published Online April 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojf http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2015.54038 Life History and Biology of the Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus kashmirensis Schedl (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Infesting Ulmus villosa in Kashmir Abdul Lateef Khanday, Abdul A. Buhroo* Postgraduate Department of Zoology, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India Email: *[email protected] Received 19 February 2015; accepted 13 April 2015; published 17 April 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Elm bark beetle Scolytus kashmirensis is a key pest of elm nurseries in the social forestry ecosys- tem of Kashmir. The biological and morphological characters of this species were determined both in field and in the laboratory. The larvae remained inactive throughout the winter which resumed their activity from the third week of March. Pupation started from the first week of April and the first swarming adults appeared from the last week of April. After emergence, the adults fly to suitable trees and undergo maturation feeding for 8.4 (±0.68 SD) days and females laid 46 (±9.45 SD) eggs on an average. The eggs hatched after an incubation period of 11 - 13 days. The five larval instars were distinguished from each other on the basis of the width of head capsule measure- ments. The larvae completed their development in 40 - 46 days. The pupal stage lasted for 10 - 20 days and finally adults emerge that lived for 45 - 60 days. -

Feeding Responses by Scolytus Scolytus to Twig Bark Extracts from Elms J

Invest Agrar: Sist Recur For (2004) 13 (1), 217-225 Feeding responses by Scolytus scolytus to twig bark extracts from elms J. A. Pajares1*, S. García1, J. J. Díez1, D. Martín2 and M. C. García-Vallejo2 1 Departamento de Producción Vegetal. Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenierías Agrarias. Universidad de Valladolid. Avda. Madrid, 44. 34002 Palencia. Spain 2 Centro de Investigación Forestal. INIA. Ctra. Coruña, km 7. 28040 Madrid. Spain Abstract Feeding responses by Scolytus scolytus were tested using elm twig bark extracts in a laboratory bioassay. One to 4- years-old elm twigs or small branches were sampled in spring and their bark extracted separately with methanol and with a mixture of petroleum ether and diethyl ether (1:1) as solvents. Bark extracts were tested in a two choice fee- ding bioassay consisting of two polyurethane discs placed in a 10 cm diameter Petri dish. Extracts were applied onto the discs and the amount of disc eaten by ten freshly emerged S. scolytus adults was recorded after 24 hours. Ten U. minor, two U. laevis, six U. glabra, three Dutch hybrids (European x Asiatic) and one U. pumila trees were tested in several comparisons. Discs with extracts from both U. laevis trees were significantly less eaten than those from U. pu- mila or from U. minor trees in two choice tests. Similarly, extracts from all U. glabra trees received less feeding than those from U. minor. On the contrary, S. scolytus showed no difference in feeding between U. pumila and U. minor ex- tracts, and similarly for Dutch hybrids in comparison with two U. -

An Assessment of Biological Control of Polygraphus Major Stebbing, 1903 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Entomopathogenic Fungi

JOURNAL OF FOREST SCIENCE, 64, 2018 (4): 178–186 https://doi.org/10.17221/140/2017-JFS An assessment of biological control of Polygraphus major Stebbing, 1903 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by entomopathogenic fungi Abdul Lateef KHANDAY*, Abdul Ahad BUHROO Section of Entomology, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Khanday A.L., Buhroo A.A. (2018): An assessment of biological control of Polygraphus major Stebbing, 1903 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by entomopathogenic fungi. J. For. Sci., 64: 178–186. Recently the use of fungal entomopathogens against bark beetles has gained increasing attention throughout the world and researchers continue to seek highly pathogenic fungal isolates for controlling beetle pests. In the present study, the efficacy of three entomopathogenic fungi, namely Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin, Metarhizium anisopliae sensu lato (Metchnikoff) Sorokin and Lecanicillium lecanii (Zimmerman) Zare & Gams, was tested against Polygra- phus major Stebbing, 1903 under laboratory conditions. Each fungal suspension contained 1.0 × 109 spores of fungi in 1 ml. An insecticide – Cyclone was also used as positive control in the experiment. The mortality caused by these fungi was recorded in treated branches and petri plate assay. In treated branches, B. bassiana and M. anisopliae s. l. caused higher mortality, i.e. 57.77 and 46%, respectively, after 10 days of treatment and 98 and 92.77%, respectively, after 20 days of treatment. The results of the petri plate assay revealed that P. major adults were highly susceptible to both applied fungal species and insecticide. However, B. bassiana and M. anisopliae s. l. -

Georgia Invasive Species Strategy

Georgia Invasive Species Strategy Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division Georgia Invasive Species Advisory Committee August 2009 Citation: Georgia Invasive Species Strategy. 2009. Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division: Social Circle, GA. This document is available on the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division web site at http://www.georgiawildlife.com/assets/documents/GeorgiaInvasiveSpeciesStrategy.pdf Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Pathways of Introduction 13 Invasive Species in Georgia 14 Framework for Invasive Species Management in Georgia 15 Federal Invasive Species Management Efforts in Georgia 15 State Invasive Species Management Efforts in Georgia 18 Nongovernmental Invasive Species Management Efforts in Georgia 24 Current Gaps in Georgia’s Authorities and Programs for Invasive Species 27 Goals, Objectives and Actions 29 Program Monitoring and Evaluation 33 Glossary of Terms 34 Literature Cited 37 Appendix A: Invasive Species of Concern in Georgia 40 Appendix B: Descriptions of Invasive Species in Georgia 49 Appendix C: Summary of Federal Laws Relevant to Invasive Species 99 Appendix D: Summary of Georgia Laws Relevant to Invasive Species 109 Appendix E: Survey Results of Invasive Species Management Activities in Georgia 119 Appendix F: Federal Noxious Weeds List 121 Appendix G: Invasive Species Pathways Outline 123 Appendix H: Members of the Georgia Invasive Species 128 Advisory Committee 2 Acknowledgements Compiled and written by Margaret Myszewski, Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia, and members of the Georgia Invasive Species Advisory Committee (Committee). In addition to the research and deliberations of the Committee, many staff members of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources contributed their knowledge and experience to the development of this plan.