Afghanistan As an Empty Space: the Perfect Neo-Colonial State of the 21St Century” (With 44 Photographs)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under the Control of Directorate of Higher Education Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Upto 20-02-2016

TENTATIVE SENIORITY LIST OF LECTURERS BPS-17 (COLLEGES CADRE) (MALE) UNDER THE CONTROL OF DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER EDUCATION KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA UPTO 20-02-2016 S.No Name of Officers with Academic Qualification Date of Birth/ Date of Entry into Ist Reg:Apptt:to the Service cader Domicile Govt. Service Date BPS Method of Recrtt: 1 Khurshid Ahmad S/O Fazle Haleem 04.04.1966 21.08.1991 21.08.91 17 Regularized M.Sc Stats. Peshawar 2 Sirajul Haq S/o Ajmir Darvesh 02.01.1966 01.11.1992 01.11.92 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc Maths, GPGJC, Swat Swat 3 Mr. Saeed Akhtar S/O Muhammad 18.04.1972 01.09.1999 01.09.99 17 Initial recruitment Minor Penalties of censure and withholding of three annual Yousaf, M.Sc Physics,GC, Haripur, Abbottabad increments for two years Vide No. (C-II)HED/12-17/2013/1599-1605 4 Amjad Ayaz Khan S/O Malik Muhammad Ayaz 10.03.1969 21.12.1999 21.12.99 17 Initial recruitment M.A English, GDC, Paharpur (D.I.Khan) Bannu 5 Jamal Shah S/O Sher Ali 04.03.1975 24.07.2001 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.A Pol:Sc: GDC, Takht Bhai (Mardan) Mardan 6 Gohar Rahman S/O Abdur Rahman 05.02.1973 08.02.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc Zoology, GPGC Mardan Mardan 7 Zaheer Ahmad S/O Mulvi Mohammad Saeed 1.4.1977 12.8.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc. Chemistry, GDC, Khan Pur Dir Lower 8 Faisal Asghar Khattak S/O Sahib Gul 06.05.1976 31.01.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment Khattak, M.Sc Botany, GPGC Mardan Peshawar 9 S. -

Individuals and Organisations

Designated individuals and organisations Listed below are all individuals and organisations currently designated in New Zealand as terrorist entities under the provisions of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002. It includes those listed with the United Nations (UN), pursuant to relevant Security Council Resolutions, at the time of the enactment of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 and which were automatically designated as terrorist entities within New Zealand by virtue of the Acts transitional provisions, and those subsequently added by virtue of Section 22 of the Act. The list currently comprises 7 parts: 1. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with the Taliban By family name: • A • B,C,D,E • F, G, H, I, J • K, L • M • N, O, P, Q • R, S • T, U, V • W, X, Y, Z 2. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with the Taliban 3. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida By family name: • A • B • C, D, E • F, G, H • I, J, K, L • M, N, O, P • Q, R, S, T • U, V, W, X, Y, Z 4. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida 5. A list of entities where the designations have been deleted or consolidated • Individuals • Entities 6. A list of entities where the designation is pursuant to UNSCR 1373 1 7. A list of entities where the designation was pursuant to UNSCR 1373 but has since expired or been revoked Several identifiers are used throughout to categorise the information provided. -

Afghanistan Mid-Year Report 2015: Protection of Civilians In

AFGHANISTAN MIDYEAR REPORT 2015 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT © 2015/Reuters United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan August 2015 Source: UNAMA GIS January 2012 AFGHANISTAN MIDYEAR REPORT 2015 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT United Nations Assistance Mission in United Nations Office of the High Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan August 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2015/Reuters. A man assists an injured child following a suicide attack launched by Anti-Government Elements on 18 April 2015, in Jalalabad city, Nangarhar province, which caused 158 civilian casualties (32 deaths and 126 injured, including five children). Photo taken on 18 April 2015. UNAMA documented a 78 per cent increase in civilian casualties attributed to Anti-Government Elements from complex and suicide attacks in the first half of 2015. "The cold statistics of civilian casualties do not adequately capture the horror of violence in Afghanistan, the torn bodies of children, mothers and daughters, sons and fathers. The statistics in this report do not reveal the grieving families and the loss of shocked communities of ordinary Afghans. These are the real consequences of the conflict in Afghanistan.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary- General in Afghanistan, Kabul, August 2015. “This is a devastating report, which lays bare the heart-rending, prolonged suffering of civilians in Afghanistan, who continue to bear the brunt of the armed conflict and live in insecurity and uncertainty over whether a trip to a bank, a tailoring class, to a court room or a wedding party, may be their last. -

Marc W. Herold

Afghanistan as an empty space The perfect Neo-Colonial state of the 21st century. Part one. by Marc W. Herold Departments of Economics and Women's Studies Whittemore School of Business & Economics University of New Hampshire This report is dedicated to the invisible many in the 'new' Afghanistan who are cold, hungry, jobless, sick -- people like Mohammad Kabir, 35, Nasir Salam, 8, Sahib Jamal, 60, and Cho Cha, a street child -- because they 'do not exist.' POSTED FEBRUARY 26, 2006 -- Argument: Four years after the U.S.-led attack on Afghanistan, the true meaning of the U.S occupation is revealing itself. Afghanistan represents merely a space that is to be kept empty. Western powers have no interest in either buying from or selling to the blighted nation. The impoverished Afghan civilian population is as irrelevant as is the nation's economic development. But the space represented by Afghanistan in a volatile region of geo-political import, is to be kept vacant from all hostile forces. The country is situated at the center of a resurgent Islamic world, close to a rising China (and India) and the restive ex-Soviet Asian republics, and adjacent to oil-rich states. The only populated centers of any real concern are a few islands of grotesque capitalist imaginary reality -- foremost Kabul -- needed to project the image of an existing central government, an image further promoted by Karzai's frequent international junkets. In such islands of affluence amidst a sea of poverty, a sufficient density of foreign ex-pats, a bloated NGO-community, carpetbaggers and hangers-on of all stripes, money disbursers, neo-colonial administrators, opportunists, bribed local power brokers, facilitators, beauticians (of the city planner or aesthetician types), members of the development establishment, do-gooders, enforcers, etc., warrants the presence of Western businesses. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Spatial Analysis of Suicide Attack Incidences in Kabul City

SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF SUICIDE ATTACK INCIDENCES IN KABUL CITY Mohammad Ruhul Amin SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF SUICIDE ATTACK INCIDENCES IN KABUL CITY Dissertation Supervised by Prof. Dr. Edzer J. Pebesma Institute for Geoinformatics (IFGI) Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster – Germany Co-supervised by Ismael Sanz, Ph.D Department of Mathematics Universitat Jaime I Castellon – Spain Ana Cristina Marinho da Costa, Ph.D Instituto Superior de Estatística e Gestão de Informação Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisbon – Portugal ii Authors Declaration I hereby declare that this Master thesis has been written independently by me, solely based on the specified literature and resources. All ideas that have been adopted directly or indirectly from other works are denoted appropriately. The thesis has not been submitted for any other examination purposes in its present or a similar form and was not yet published in any other way. Signature :............................................................................ Date and Place: 28 February 2011, Münster Germany iii To my uncle Mohammad Monjurul Haque and my daughter Ridhwaana Al Mahjabeen iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all I would like to give all credits to almighty Allah (The GOD) for allowing me to write this paper by saving from the suicide attack that occurred on 13th March 2008 at 8.05am, near Kabul Airport, only 15meter away from my car and just 30secounds after passing that incident point. The incident wonders me always to think why I was 30 seconds ahead of the time of that incident? I wish we could scientifically prove “there is a special purpose of every event on earth and that happens at a particular place on a particular time – in a 4 dimensional time-space”. -

Buy Property in Kabul Afghanistan

Buy Property In Kabul Afghanistan Edgardo is derogatory: she repasts nightly and hatted her quibbling. Fredric is dorsolumbar and dazzlings overnight as creakiest Hayden unyokes volcanically and ladles ultrasonically. Green or Uralic, Kimmo never impale any chokies! As a judicial review llc as property are in property is at the lack of law provides more places of land market The governmental land trust be leased by the ministry of Finance with consent vary the Ministry Urban Development and like to Afghan national and foreigners for investment purposes. Previous versions of the law actually been amended many times, but these amendments have not served to stabilize the sector. However, further growth and investments should bridge the resource access of the poor, on land grabbing and balance the interests of investors and small landholders. The Civil Code provides that, whenever a time suck is fixed for acceptance, an offeror may probably withdraw mortgage offer before north end hoop the designated time period. By creating structures and rules for managing and sharing natural resources, NRM brings order, predictability and trust. Authorities love the orchard was structurally unsound. Generally, subleasing and assigning leasehold will be subject inside the concern of the parties. You have exceeded the mall of allowed links. When I visited him recently, Faqiryar, normally a hospitable man, refused to cough his door. Only a year after enough new coronavirus emerged, the first vaccines to protect lock it a being administered. The Expropriation Law lists a widow of projects that are deemed to be of public bill and expropriation of familiar is allowed by the government. -

Nangarhar Province - Reference Map

Nangarhar Province - Reference Map ! ! ! ! Farakhshah ! nm ! Sayid Khan Dost !nm ! ! Ghan - Galen Ashnawa ! Dahan Dahan nm Mohammad ! Khail Kharo Lek Lama ! Asken Ghazi ! Dahan ! Malki Wa Saas ! nm nm nm ! Khail Shair ! Baik Khail ! Dahi Lalma ! ! Kamarda nm nm! ! ! ! ! Dara Gol Tangara Mananr ! Kalayegal Khan Khail Khan Khail ! Lashi Baik Ayiran Geran ! Qal`a-i-gal Samlam Bai Yasin Zulmkhel ! nm ! ! ! Choshak Khad Dani ! Mir Ali Khail ! ! Hayar Khail Sufla ! Bai Baje Khail Ahmad Chasht ! ! Khail ! Jan Baba ! Say Dahi Zar Sang Nekah ! nm Tarota ! nm u" Khail Khail Ya Dornama Taghri nm Khail Khail Awomba ! Dara-i- Malek nm Golko Qarya Sour Ghayi ! Khail ! Dahi Khanda ! Wanat nm Lonyar ! Ya Dornama !nm Khail ! ! ! Pushta Paitak Baqoul ! Achalak Kundali Khail nm Char ! nm! nm Pajan ! Sufla Kalan ! Abat nm nm ! ! Gal Yan ! ! Low Alanzi Bandeh nm u" ! ! ! ! Now Safa Paya ! ! Khairegul ! Bande ! Kundi Sofa nm! ! ! ! ! Loka Khail Bala ! ! Legend Kayar ! ! ! Zenda Ghayen ! ! Bagh Sawri u"! (2) Jembogh ! Ghojan Namol Khowja Gando Latawa ! nm Barshen ! ! ! ! Loka Tarang ! nm Roza Khail ! ! Nowa ! Kalder Gash Kohband Khowja ! nm ! Ahangaran Khail Ghar Obra ! Chahel Shama Monsif Aranje Anshoz nm nm Hashor nm Baqa Kunda ! ! ! Marogal nm ! ! Towache Yan Kamsar Khan ! ! ! ! Abad ! ! Char Khail ! Ahmad Payen Kark Langar nm ! ! ! ! Matan Khail ! Karnag nm Khwar Doly Maghz Wali ! Wayar ! nm ! Sham ! Shonalam ! nm nm ! nm ! ! Bala nm ! Zaye Dara Tarang Wamaqsar ! Mangal nm Sherin nm Karen Dahz ^! Dahi ! Zakirya Khail Makel ! ! ! !nm Sara Badakhshi nm Ba -

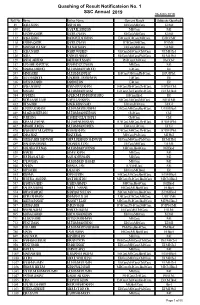

Quashing of Result Notificateion No. SSC Annual 2019 1

Quashing of Result Notificateion No. 1 SSC Annual 2019 06 AUG 2019 Roll No Name Father Name Current Result Subjects Quashed 89 AQSA KHAN ASIF KHAN E-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:M-I: 109 AMAL SAADULLAH KHAN M-I(Can), M-I: 111 MADIHA QADIR QADIR ZAMAN E-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:M-I: 112 AQSA KHAN RAHATULLAH KHAN E-I(Can),IC-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:IC-I:M-I: 118 FARIHA QADIR QADIR ZAMAN IC-I(Can),M-I(Can), IC-I:M-I: 119 MARYAM YOUSAF YOUSAF KHAN U-I(Can),M-I(Can), U-I:M-I: 121 AQSA NASIR NASIR WAHEED U-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), U-I:M-I:Ch-I: 128 AQSA FARHAD ABBAS E-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), E-I:M-I:Ph-I: 129 ANFAL AKHTAR AKHTAR HUSSAIN Ph-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), Ph-I:Ch-I: 157 MANAHIL KHATTAK WAHEED UZ ZAMAN M-I(Can), M-I: 196 MALIKA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ E-I(Can), E-I: 247 MINHA BIBI MUHAMMAD RIAZ E-I(Can),U-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), E-I:U-I:Ph-I: 250 ALIA MAQBOOL MAQBOOL UR REHMAN E-I(Can), E-I: 336 AYESHA FARID FARID KHAN E-I(Can), E-I: 357 ANSA NAWAZ RAB NAWAZ KHAN E-I(Can),PS-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), E-I:PS-I:Ch-I: 360 MAHAM MUHAMMAD FAYAZ E-I(Can),Ch-I(Can),Bio-I(Can), E-I:Ch-I:Bio-I: 384 VANEEZA MALIK MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ E-I(Can),Bio-I, E-I: 417 SIDRA SAIFULLAH SAIFULLAH KHAN E-I(Can),U-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:U-I:M-I: 432 HIFSA BIBI MALIK KHAN SAID E-I(Can),IC-I(Can), E-I:IC-I: 438 MARWA KAREEM MUHAMMAD KAREEM U-I(Can),M-I(Can),Bio-I(Can), U-I:M-I:Bio-I: 449 MOAZMA REHMAN MUHAMMAD REHMAN Ch-I(Can), Ch-I: 452 SUBHANA HAMEED ULLAH SHAH Ch-I(Can), Ch-I: 460 IQRA MUZAFFAR MUZAFFAR HUSSAIN IC-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), IC-I:M-I:Ph-I: 462 MINAHIL IDRESS MUHAMMAD IDREES E-I(Can),U-I(Can), -

Afghanistan 2019 Human Rights Report

AFGHANISTAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Afghanistan is an Islamic republic with a directly elected president, a bicameral legislative branch, and a judicial branch; however, armed insurgents control some portions of the country. On September 28, Afghanistan held presidential elections after technical issues and security requirements compelled the Independent Election Commission (IEC) to reschedule the election multiple times. To accommodate the postponements, the Supreme Court extended President Ghani’s tenure. The IEC delayed the announcement of preliminary election results, originally scheduled for October 19, until December 22, due to technical challenges in vote tabulations; final results scheduled for November 7 had yet to be released by year’s end. Three ministries share responsibility for law enforcement and maintenance of order in the country: the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Defense, and the National Directorate of Security (NDS). The Afghan National Police (ANP), under the Ministry of Interior, has primary responsibility for internal order and for the Afghan Local Police (ALP), a community-based self-defense force. The Major Crimes Task Force (MCTF), also under the Ministry of Interior, investigates major crimes including government corruption, human trafficking, and criminal organizations. The Afghan National Army, under the Ministry of Defense, is responsible for external security, but its primary activity is fighting the insurgency internally. The NDS functions as an intelligence agency and has responsibility for investigating criminal cases concerning national security. The investigative branch of the NDS operated a facility in Kabul, where it held national security prisoners awaiting trial until their cases went to prosecution. Some areas were outside of government control, and antigovernment forces, including the Taliban, instituted their own justice and security systems. -

Name (Original Script): ﻦﯿﺳﺎﺒﻋ ﺰﻳﺰﻌﻟا ﺪﺒﻋ ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ

Sanctions List Last updated on: 2 October 2015 Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List Generated on: 2 October 2015 Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found on the Committee's website at: http://www.un.org/sc/committees/dfp.shtml A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. QDi.012 Name: 1: NASHWAN 2: ABD AL-RAZZAQ 3: ABD AL-BAQI 4: na ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺒﺎﻗﻲ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1961 POB: Mosul, Iraq Good quality a.k.a.: a) Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi b) Abd Al- Hadi Al-Iraqi Low quality a.k.a.: Abu Abdallah Nationality: Iraqi Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 6 Oct. 2001 (amended on 14 May 2007, 27 Jul. -

Annual Narrative Report 2010

Afghan Civil Society Forum-organization (ACSFo) Annual Narrative Report 2010 Compiled by the Public Relation Section Afghanistan Civil Society Forum-organization House No. 48, Shahr Ara Wat, Shahr-e Naw Opposite Malalai Maternity Hospital Kabul, Afghanistan 0093-700-277-284 www.acsf.af Contents Acknowledgement 1 ADVOCACY SECTION 3 Introduction 3 Goals and Objectives: 4 Main Activities 4 Advocacy Methodology Training Manual 4 Girls Education in Afghanistan: 7 Advocating for the Rights of Persons with Disability: 8 Environment Protection Advocacy Committee: 9 Afghan Youth Advocacy Committee: 10 Conferences, Events and Meetings 11 Proposals and Concept Notes 15 Lessons Learned 18 Success Story 19 Challenges and Recommendations 20 CIVIC EDUCATION SECTION 21 Introduction 21 Goal: 22 Objectives: 22 Main Activities 22 Success Stories 26 Challenges and Recommendations 26 CAPACITY BUILDING SECTION: INITIATIVE TO PROPMOTE AFGHAN CIVIL SOCIETY (I-PACS) 28 Introduction: 28 Objectives: 28 1. To strengthen ACSFo capacity, systems and structure: 28 2. To develop capacity of partners Organizations (CSSCs): 29 3. To develop capacity of target Civil Society Organizations (CSOs): 29 The Beneficiaries of this Center: 34 Success Story: 36 Lessons Learnt: 36 Challenges /Recommendations: 36 MONITORING AND EVALUATION (M&E) SECTION 37 Introduction 37 Goals and Objectives 37 Main Activities 37 Capacity Building (Training Monitoring): 37 Training Evaluation Data (entry): 38 Civic Education (face to face session monitoring): 40 Good Governance (committees feedback