Marc W. Herold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under the Control of Directorate of Higher Education Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Upto 20-02-2016

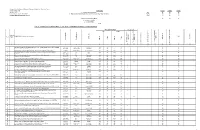

TENTATIVE SENIORITY LIST OF LECTURERS BPS-17 (COLLEGES CADRE) (MALE) UNDER THE CONTROL OF DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER EDUCATION KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA UPTO 20-02-2016 S.No Name of Officers with Academic Qualification Date of Birth/ Date of Entry into Ist Reg:Apptt:to the Service cader Domicile Govt. Service Date BPS Method of Recrtt: 1 Khurshid Ahmad S/O Fazle Haleem 04.04.1966 21.08.1991 21.08.91 17 Regularized M.Sc Stats. Peshawar 2 Sirajul Haq S/o Ajmir Darvesh 02.01.1966 01.11.1992 01.11.92 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc Maths, GPGJC, Swat Swat 3 Mr. Saeed Akhtar S/O Muhammad 18.04.1972 01.09.1999 01.09.99 17 Initial recruitment Minor Penalties of censure and withholding of three annual Yousaf, M.Sc Physics,GC, Haripur, Abbottabad increments for two years Vide No. (C-II)HED/12-17/2013/1599-1605 4 Amjad Ayaz Khan S/O Malik Muhammad Ayaz 10.03.1969 21.12.1999 21.12.99 17 Initial recruitment M.A English, GDC, Paharpur (D.I.Khan) Bannu 5 Jamal Shah S/O Sher Ali 04.03.1975 24.07.2001 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.A Pol:Sc: GDC, Takht Bhai (Mardan) Mardan 6 Gohar Rahman S/O Abdur Rahman 05.02.1973 08.02.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc Zoology, GPGC Mardan Mardan 7 Zaheer Ahmad S/O Mulvi Mohammad Saeed 1.4.1977 12.8.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment M.Sc. Chemistry, GDC, Khan Pur Dir Lower 8 Faisal Asghar Khattak S/O Sahib Gul 06.05.1976 31.01.2002 23.7.2005 17 Initial recruitment Khattak, M.Sc Botany, GPGC Mardan Peshawar 9 S. -

Nangarhar Province - Reference Map

Nangarhar Province - Reference Map ! ! ! ! Farakhshah ! nm ! Sayid Khan Dost !nm ! ! Ghan - Galen Ashnawa ! Dahan Dahan nm Mohammad ! Khail Kharo Lek Lama ! Asken Ghazi ! Dahan ! Malki Wa Saas ! nm nm nm ! Khail Shair ! Baik Khail ! Dahi Lalma ! ! Kamarda nm nm! ! ! ! ! Dara Gol Tangara Mananr ! Kalayegal Khan Khail Khan Khail ! Lashi Baik Ayiran Geran ! Qal`a-i-gal Samlam Bai Yasin Zulmkhel ! nm ! ! ! Choshak Khad Dani ! Mir Ali Khail ! ! Hayar Khail Sufla ! Bai Baje Khail Ahmad Chasht ! ! Khail ! Jan Baba ! Say Dahi Zar Sang Nekah ! nm Tarota ! nm u" Khail Khail Ya Dornama Taghri nm Khail Khail Awomba ! Dara-i- Malek nm Golko Qarya Sour Ghayi ! Khail ! Dahi Khanda ! Wanat nm Lonyar ! Ya Dornama !nm Khail ! ! ! Pushta Paitak Baqoul ! Achalak Kundali Khail nm Char ! nm! nm Pajan ! Sufla Kalan ! Abat nm nm ! ! Gal Yan ! ! Low Alanzi Bandeh nm u" ! ! ! ! Now Safa Paya ! ! Khairegul ! Bande ! Kundi Sofa nm! ! ! ! ! Loka Khail Bala ! ! Legend Kayar ! ! ! Zenda Ghayen ! ! Bagh Sawri u"! (2) Jembogh ! Ghojan Namol Khowja Gando Latawa ! nm Barshen ! ! ! ! Loka Tarang ! nm Roza Khail ! ! Nowa ! Kalder Gash Kohband Khowja ! nm ! Ahangaran Khail Ghar Obra ! Chahel Shama Monsif Aranje Anshoz nm nm Hashor nm Baqa Kunda ! ! ! Marogal nm ! ! Towache Yan Kamsar Khan ! ! ! ! Abad ! ! Char Khail ! Ahmad Payen Kark Langar nm ! ! ! ! Matan Khail ! Karnag nm Khwar Doly Maghz Wali ! Wayar ! nm ! Sham ! Shonalam ! nm nm ! nm ! ! Bala nm ! Zaye Dara Tarang Wamaqsar ! Mangal nm Sherin nm Karen Dahz ^! Dahi ! Zakirya Khail Makel ! ! ! !nm Sara Badakhshi nm Ba -

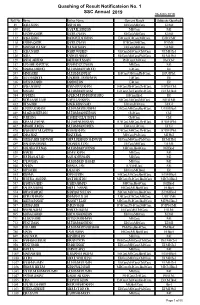

Quashing of Result Notificateion No. SSC Annual 2019 1

Quashing of Result Notificateion No. 1 SSC Annual 2019 06 AUG 2019 Roll No Name Father Name Current Result Subjects Quashed 89 AQSA KHAN ASIF KHAN E-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:M-I: 109 AMAL SAADULLAH KHAN M-I(Can), M-I: 111 MADIHA QADIR QADIR ZAMAN E-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:M-I: 112 AQSA KHAN RAHATULLAH KHAN E-I(Can),IC-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:IC-I:M-I: 118 FARIHA QADIR QADIR ZAMAN IC-I(Can),M-I(Can), IC-I:M-I: 119 MARYAM YOUSAF YOUSAF KHAN U-I(Can),M-I(Can), U-I:M-I: 121 AQSA NASIR NASIR WAHEED U-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), U-I:M-I:Ch-I: 128 AQSA FARHAD ABBAS E-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), E-I:M-I:Ph-I: 129 ANFAL AKHTAR AKHTAR HUSSAIN Ph-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), Ph-I:Ch-I: 157 MANAHIL KHATTAK WAHEED UZ ZAMAN M-I(Can), M-I: 196 MALIKA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ E-I(Can), E-I: 247 MINHA BIBI MUHAMMAD RIAZ E-I(Can),U-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), E-I:U-I:Ph-I: 250 ALIA MAQBOOL MAQBOOL UR REHMAN E-I(Can), E-I: 336 AYESHA FARID FARID KHAN E-I(Can), E-I: 357 ANSA NAWAZ RAB NAWAZ KHAN E-I(Can),PS-I(Can),Ch-I(Can), E-I:PS-I:Ch-I: 360 MAHAM MUHAMMAD FAYAZ E-I(Can),Ch-I(Can),Bio-I(Can), E-I:Ch-I:Bio-I: 384 VANEEZA MALIK MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ E-I(Can),Bio-I, E-I: 417 SIDRA SAIFULLAH SAIFULLAH KHAN E-I(Can),U-I(Can),M-I(Can), E-I:U-I:M-I: 432 HIFSA BIBI MALIK KHAN SAID E-I(Can),IC-I(Can), E-I:IC-I: 438 MARWA KAREEM MUHAMMAD KAREEM U-I(Can),M-I(Can),Bio-I(Can), U-I:M-I:Bio-I: 449 MOAZMA REHMAN MUHAMMAD REHMAN Ch-I(Can), Ch-I: 452 SUBHANA HAMEED ULLAH SHAH Ch-I(Can), Ch-I: 460 IQRA MUZAFFAR MUZAFFAR HUSSAIN IC-I(Can),M-I(Can),Ph-I(Can), IC-I:M-I:Ph-I: 462 MINAHIL IDRESS MUHAMMAD IDREES E-I(Can),U-I(Can), -

Afghanistan As an Empty Space: the Perfect Neo-Colonial State of the 21St Century” (With 44 Photographs)

1 “Afghanistan as an Empty Space: the Perfect Neo-Colonial State of the 21st Century” (with 44 photographs) by Marc W. Herold Departments of Economics and Women’s Studies Whittemore School of Business & Economics University of New Hampshire Durham, N.H. 03824 [email protected] revised and updated April 2006 source: http://www.overlandstory.com/go/albums/userpics/baluchistan/normal_baluchistan004.jpg 2 For the invisible many in the “new” Afghanistan who are cold, hungry, jobless, sick – people like Mohammad Kabir, 35, Nasir Salam, 8, Sahib Jamal, 60, and Cho Cha, a street child – because they “do not exist” Argument: Four years after the U.S.-led attack upon Afghanistan, the true meaning of the U.S occupation is revealing itself. Afghanistan represents merely a space that is to be kept empty. Western powers have no interest in either buying from or selling to the blighted nation. The country possesses no exports of interest. The impoverished Afghan civilian population is as irrelevant as is the nation’s economic development. But the space represented by Afghanistan in a volatile region of geo-political import, is to be kept vacant from all hostile forces. The country is situated at the center of a resurgent Islamic world, close to a rising China (and India) and the restive ex-Soviet Asian republics, and adjacent to oil-rich states. The only populated centers of any real concern are a few islands of grotesque capitalist imaginary reality – foremost Kabul – needed to project the image of an existing central government, an image further promoted by Karzai’s frequent international junkets. -

UNSC Asks Taliban to Enter Peace Negotiations with Kabul

www.outlookafghanistan.net www.thedailyafghanistan.com facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan facebook.com/The.Daily.Afghanistan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Add: In front of Habibia High School, Add: In front of Habibia High School, District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Back Page August 29, 2018 Jalalabad Clear Ghazni Clear Kandahar Clear Mazar Clear Herat Clear Bamiyan Clear Kabul Clear Daily 39°C 37°C Outlook 32°C 31°C 33°C 21°C 32°C Weather 30°C 16°C 24°C 23°C 19°C 6°C 18°C Forcast $5.6m Canadian Project UNSC Asks Taliban to Enter for Afghan Women Panned KABUL - A $5.6 million Ca- Peace Negotiations with Kabul nadian-funded project for boosting women’s capacity The United Nations Security Council has to influence decision-making processes has come in for flak. called for the Taliban to reciprocate without delay Launched by the Harper ad- President Ashraf Ghani’s offer of a ceasefire. ministration in 2013, Pro- moting Women’s Political Participation in Afghanistan (PWPPA) was delivered be- tween May 2014 and July 2016. Too little of the money went to the women the programme was designed to support, ac- executed. It followed Cana- hired an Italian consultant group cording to an independent da’s 2011 withdrawal of com- to assess the project’s perfor- evaluation obtained by CBS bat troops from Afghanistan mance. News. Global Affairs Canada, which The $114,000 evaluation suggests Aimed to encourage women to contracted the project to the the project said: “[T]he design of run for political office, the pro- Washington-based National the project shows several weak- ject was poorly designed and Democratic Institute (NDI), nesses, ...(More on P4)...(4) Call to Bring Afghan At Least 3,000 Working on Paktia’s Businessmen Under Tax Net Neglected Bee Farms GARDEZ - Southeastern Paktia province produces 700 tonnes of honey annually, say officials of the Agriculture and Livestock Depart- ment. -

Dispenser Course

Intermediate with Science & Diploma in Pharmacy Technician / Dispenser Course. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Scoring Key: 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 18-32 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks S.S.C 30 22 18 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) F.A/FSc 30 22 18 Dispenser pharmacy technician (BPS-12) Total;- 60 44 36 3. Professional Training Marks 20 15 12 4. Experience Certificate 5. Interviews Marks Total;- LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF DISPENSER PHARMACY TECHNICIAN BPS-12 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Total Marks Marks Marks B.A Dateof Birth Qualification Marks M.A Division Division Marks Experience of Professional/Training Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Above One Stage Interview MarksInterview Marks 8 Two Stage Above 10 10 Above Two Stage Year of Experience of Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Muhammad Israr S/o Gul Muhammad, Room no.1 nursing hospital rehan medical institute 1 10/4/1991 Intermediate Malakand 3rd 18 18 36 36 hayatabad phase V peshawar. 3rd 2 kameen khan s/o madat khan, post office magan bhagan district kurm agency 1/4/2014 Intermediate Kurran agency 1st 30 2nd 22 52 52 Muhammad sadiq s/o Muhammad Humayon, house no. H308, street no.D3 phase 1 3 21-04-1992 B.A kark 2nd 22 2nd 22 44 44 hayatabad. -

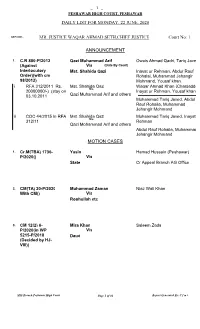

SINGLE BENCH LIST for 22-06-2020(MONDAY)===.Xps

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 22 JUNE, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. C.R 880-P/2012 Qazi Muhammad Arif Owais Ahmad Qadri, Tariq Javed (Against V/s (Date By Court) Interlocutory Mst. Shahida Qazi Inayat ur Rehman, Abdur Rauf Order)(with cm Rohalai, Muhammad Jehangir 98/2012) Mohmand, Yousaf khan i RFA 312/2011 Rs. Mst. Shahida Qazi Waqar Ahmad Khan (Charsadda), V/s 20000000/-) (stay on Inayat ur Rehman, Yousaf khan 03.10.2011 Qazi Muhammad Arif and others Muhammad Tariq Javed, Abdul Rauf Rohaila, Muhammad Jehangir Mohmand ii COC 44/2015 In RFA Mst. Shahida Qazi Muhammad Tariq Javed, Inayat ur V/s 312/11 Rehman Qazi Mohammad Arif and others Abdul Rauf Rohaila, Muhammad Jehangir Mohmand MOTION CASES 1. Cr.M(TBA) 1736- Yasin Hamad Hussain (Peshawar) P/2020() V/s State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 2. CM(TA) 20-P/2020 Muhammad Zaman Niaz Wali Khan With CM() V/s Roohullah etc 3. CM 12(2) 6- Mira Khan Saleem Zada P/2020(in WP V/s 5215-P/2018 Daud (Decided by HJ- VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 92 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 22 JUNE, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 4. C.R 139-P/2019 Barrister Jehanzeb Rahim Naveed Maqsood Sethi, Abdul With CM V/s Sattar Khan 468/2020() Dr. Salim Javed i C.R 184/2019 With Mst. -

AFGHANISTAN: Laghman Province Reference Map

AFGHANISTAN Laghman Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Laghman Province Reference Map 70°0'0"E 70°30'0"E Dara / Ab Shar District Panjsher Province Duab District Mandol District Duab ! Nuristan Province Dawlatshah Nurgeram District District Chapadara District 35°0'0"N 35°0'0"N Dawlatshah ! Nurgeram ! Kapisa Province Alasay District Alingar Tagab ! District Alishang Alingar District Alishang District ! Kabul Laghman Province Province Surobi District Dara-e-Nur District Mehtarlam Dara-e-Nur ! ! Mehtarlam !! / Bad Pash District Kuzkunar ! Kuzkunar District Qarghayi ! Qarghayi Behsud District District 34°30'0"N 34°30'0"N Nangarhar Province Jalalabad Kama !! District Surkhrod ! Behsud Surkhrod ! Khogyani District o District Hesarak District 70°0'0"E 70°30'0"E Legend Date Printed: 27 March 2014 01:34 PM UZBEKISTAN CHINA Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI TAJIKISTAN ^! Capital o Airport Schools - Ministry of Education !! Provincial Center ° TURKMENISTAN Health Facilities - Ministry of Health p Airfield ! District Center River/Stream Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 JAMMU AND Administrative Boundaries River/Lake 0 20 Kms KASHMIR International Kabul ^! Province Disclaimers: Distirict The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Transportation Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Primary Road PAKISTAN delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

News Corners

News Corners . LUMS and Library News Indexing of News Papers . The News, Dawn, Business Recorder, The Nation New Book List . List of New Arrivals Journal table of Contents . Business, Social Sciences, Law, Science & Engineering Indexing of SCOPUS Publications . LUMS publications Book of the Month . Best seller book Monthly Library Statistics . e‐databases, portals, website, circulation usage News Corner LUMS Students Connect with Peers at the Kashmir National Youth Summit Pakistani. The exhausted LUMS student struggling to pay attention after 12 hours of travel. Pakistani. The girl from Hazara, Quetta narrating the story of her life in the constant shadow of fear and discrimination. Pakistani. The students from the KIU nimbly jumping across the hill of Pir Chinasi and throwing snowballs at each other. All Pakistani. Between October 17-19, 2018 students from across the country convened in the halls of The University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir for the ‘Fourth National Youth Conference on Peace Building and National Integration’, a four-day conference meant to create a platform for the youth to inspire and be inspired, to share and to hear stories, to sing and dance and represent, to celebrate their differences and to celebrate the fact that we are still all Pakistani…..read more LUMS Management Science Student Attends United Nations Conference on Trade and Development The number of youth between the ages of 15 and 24 is 1.1 billion; youth constitute 18 percent of the global population. This percentage is the highest that the world has ever seen and is specifically the reason that countries across the globe and the United Nations are taking up initiatives to promote the voice of the youth. -

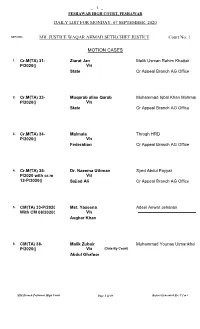

Single Benlch List for 07-09-2020

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 07 SEPTEMBER, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 1. Cr.M(TA) 31- Ziarat Jan Malik Usman Rahim Khattak P/2020() V/s State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 2. Cr.M(TA) 33- Muqarab alias Qarab Muhammad Iqbal Khan Mohmand P/2020() V/s State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 3. Cr.M(TA) 34- Malmala Throgh HRD P/2020() V/s Federation Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 4. Cr.M(TA) 35- Dr. Naeema Uthman Syed Abdul Fayyaz P/2020 with cr.m V/s 12-P/2020() Sajjad Ali Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 5. CM(TA) 33-P/2020 Mst. Yaseena Adeel Anwar Jehangir With CM 08/2020() V/s Asghar Khan 6. CM(TA) 38- Malik Zubair Muhammad Younas Utmankhel P/2020() V/s (Date By Court) Abdul Ghafoor MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 98 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 07 SEPTEMBER, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 7. CM(TA) 43- Muhammad Tariq Khan Advocate General P/2020(in wp V/s 1562-A/2019) Gopvt 8. CM(TA) 44- Caste Jalal Khel through elders Abdul Lateef Afridi P/2020(in wp 360- Feroz Khan D/2019) V/s Govt 9. CM Corr 300- Ayaz Fayaz Anwar (Nowshehra) P/2020(in BA 711- V/s P/2020 (Decided State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office by HCJ)) 10. -

Final Version EC

Wesleyan ♦ University Global Cultural Flows and the Post-9/11 Secularization of Sufi Music of Pakistan By Muhammad Usman Malik Faculty Advisor: Dr. Eric Charry A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Middletown, Connecticut May 2015 Abstract Global Cultural Flows and the Post-9/11 Secularization of Sufi Music of Pakistan explores the development of Sufi music of Pakistan since the events of September 11, 2001. It involves the association of Sufi music with contemporary social concepts and issues, the rise of non-ritual Sufi compositions and non-hereditary Sufi musicians to popularity, and the increasing presence of Sufi music on social media and regional film and TV. I call these transformations the secularization of Sufi music of Pakistan. I demonstrate that the secularization is happening due to disjunctive global flows of ideas, money, and media. I present four case studies to substantiate this claim. The first concerns Punjabi Sufi musician Sain Zahoor’s unusual movement from obscurity to stardom. This change is driven in part by certain US policy initiatives to modernize the Islamic world to address Muslim violence against the West. The second, Zahoor’s composition “Allah hoo” (God is) from the Pakistani film Khuda Ke Liye, concerns how this new transformation of Sufi music is constructing a liberal Islamic perspective in the context of global Muslim feminism. The third examines the transformation of jugni, a popular Punjabi genre, into a Sufi genre, attributing it to the multinational Coca Cola corporation’s attempts to construct a multicultural Pakistani identity. -

Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 2-7-1966 Kabul Times (February 7, 1966, vol. 4, no. 261) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (February 7, 1966, vol. 4, no. 261)" (1966). Kabul Times. 935. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/935 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , .' ~TBEB FORECAST PAGE 4 KABUL TIMES FEBRUARY 6, 1966 lI/EWS STALLS Tomorrow~ Tempenau. ltabul Ttmes is available at: His Khyber Resburant; IUbuJ .>, Majesty Sends Afghan Poets To Attend Amir Khisro Anniversary AT THE CINEMA • Max.. +12°C. Minimum -O°C. Ceylon Congratulations Sun sets tomorrow at 5:26 p.m. a,tel; Share..eNa* near Park. On National Day ARIANA CINEMA Sun rises tomorrow at 6:41 :un. Cinema; Kabul l1lternJltlol1:l1 At 2, 4:30, 7 and. 9 p.m. Aernri· Tomorrow's Outlook: Cloudy AIrport. ' KABUL. Feb. 6.--00 the occa can film.starring Charlie- Chaplin. , meS~ sion of Ceylon's "national day a 30 YEARS OF FUN sage: of congratulation' has been sent 'PRICE AJ.. " PARK CINEMA KABUL. M0NDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 1906, (DALV IB, 1:H4, S.H.) \ to Colomho on behalf of His Ma A.t. 2:30, 5, 7:30 and' 9:30 p.rn.