S. Harrison 1 Trash Or Treasure in the Works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Stream South Park Online Free No Download Stream South Park Online Free No Download

stream south park online free no download Stream south park online free no download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbdf08ddb7c40b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Stream south park online free no download. Watch full episodes of your favorite shows with the Comedy Central app.. Enjoy South Park, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Broad City and many more, . New episodes of “South Park” will now go through many windows — on television on Comedy Central, on the web at SouthParkStudios for . How to watch South Park on South Park Studios: · Go to: http://southpark.cc.com/.. · Select “Full episodes” from the top menu.. south park episodes. South Park Zone South Park Season 23.. Watch all South Park episodes from Season 23 online . "Mexican Joker" is the first episode of the twenty-third season of . seasons from many popular shows exclusively streaming on Hulu including Seinfeld, Fargo, South Park and Fear the Walking Dead. -

(The Musical) Is Awesomely Lame | Culture | Religion Dispatches

REVIEW June 12, 2011 Why The Book of Mormon (the Musical) is Awesomely Lame Never mind the Tony awards and all the acclaim, Broadway's best is not all that. By JARED FARMER The Book of Mormon cleaned up at this year's Tony Awards, winning nine of the 14 awards it was nominated for, including Best Musical. But tonight's success is hardly unexpected, capping off, as it does, an extraordinary season of critical adulation. What’s going on? Why has a good-not-great religious satire from the creators of South Park received rapturous praise from the whole canon of media tastemakers? It may be true that The Book of Mormon is the second best musical début (behind American Idiot) on the Great White Way in recent memory, but that’s really not saying much. In a season devoted mainly to re-runs, revivals, and adaptations, The Book of Mormon stands out for being a first-run play with an original score and book. Also, while the musical adheres to 1950s Broadway conventions— tunefulness, campiness, and uplift—it's modishly vulgar. The Book of Arnold? The plot concerns two unprepared and ill-paired missionaries, a pious hunk and a delusional geek, sent from Utah to Uganda. There the rural villagers suffer from AIDS, dysentery, and political violence. The Ugandans say they have no use for this American religion; it doesn’t help their situation. But when the chubby, bespectacled geek—a Mormon who has never read the Book of Mormon—invents “scriptural” stories in the form of practical allegories, with embellishments borrowed from Star Trek, Star Wars, and Lord of the Rings, the Africans respond enthusiastically. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

Edition 4 | 2018-2019

2018-2019 SEASON Letter from the Chairman 9 Letter from the CEO 11 The Book of Mormon 14 Palace Theater Staff Directory 30 Program information for tonight’s presentation inside. The Palace would like to thank all of its Program advertisers for their support. ADVERTISING Onstage Publications Advertising Department 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business, Inc. Contents ©2019. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. letter from the chairman s Chairman of the Board of Directors for the Palace A Theater, I am grateful for the opportunity to serve this organization, and enthusiastic about its future. Committed to fostering the Palace’s success, the Board of Directors is currently working on a new three-year Strategic Business Plan, which will chart out the artistic, organizational, and financial goals for the theater. Focusing on expanded arts and educational programming, marketing, capital projects, and financial development, the objective of the plan is to continue expanding our current entertainment initiatives and ensure financial sustainability and growth for the Palace for years to come. Artistic success and economic stability help us provide a welcoming stage for both local and national arts groups. While we consistently seek out top-tier productions and popular artists, we also look to foster the next generation of talent, through our partnership with the Waterbury Arts Magnet Schools and our own educational programs. -

The Noteworthy Life of Howard Barnes at Village Theatre Encore

SEPTEMBER 2018 September 2018 Volume 18, No. 1 RECEIVINGBR STANDING OVATIONS AVO! & RAVE REVIEWS FROM PATIENTS · Sports Medicine · Foot & Ankle · Spine Surgery · Joint Replacement · Hand & Wrist · Surgery Center Paul Heppner President Board Certified Orthopedic Surgeons Mike Hathaway Vice President (425) 339-2433 Kajsa Puckett www.ebjproliancesurgeons.com Vice President, Marketing & Business Development Genay Genereux EAP 1_6 H template.indd 1 9/30/16 11:56 AM Accounting & Office Manager Production Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Jennifer Sugden Assistant Production Manager Ana Alvira, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Designers Sales Amelia Heppner, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Joey Chapman, Brieanna Hansen, Ann Manning, Wendy Pedersen Seattle Area Account Executives Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Marketing Shaun Swick Senior Designer & Digital Lead Ciara Caya Marketing Coordinator Encore Media Group Corporate Office 425 North 85th Street Seattle, WA 98103 p 800.308.2898 | 206.443.0445 f 206.443.1246 [email protected] www.encoremediagroup.com APPARITIONS Encore Arts Programs and Encore Stages are published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events & in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. All rights reserved. ©2018 Encore Media Group. Reproduction without SPELLBOUND written permission is prohibited. September 18 through November 18, 2018 Opening Reception September 21, 2018 6pm – 8pm, FREE Image: Marlene Seven Bremner. The Transfiguration of Thoth. Oil on canvas. 620 Market Street Kirkland, WA 98033 kirklandartscenter.org 2 VILLAGE THEATRE ROBB HUNT Executive Producer JERRY DIXON Artistic Director Book and Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Music by Michael Kooman Francis J. Gaudette Theatre Everett Performing Arts Center September 13 – October 21, 2018 October 26 – November 18, 2018 Director BRANDON IVIE Choreographer Music Director Scenic Designer AL BLACKSTONE R.J. -

Religion As a Role: Decoding Performances of Mormonism in the Contemporary United States

RELIGION AS A ROLE: DECODING PERFORMANCES OF MORMONISM IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED STATES Lauren Zawistowski McCool A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Dr. Jonathan Chambers Dr. Lesa Lockford © 2012 Lauren Zawistowski McCool All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Although Mormons have been featured as characters in American media since the nineteenth century, the study of the performance of the Mormon religion has received limited attention. As Mormonism (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) continues to appear as an ever-growing topic of interest in American media, there is a gap in discourse that addresses the implications of performances of Mormon beliefs and lifestyles as performed by both members of the Church and non-believers. In this thesis, I closely examine HBO’s Big Love television series, the LDS Church’s “I Am a Mormon” media campaign, Mormon “Mommy Blogs” and the personal performance of Mormons in everyday life. By analyzing these performances through the lenses of Stuart Hall’s theories of encoding/decoding, Benedict Anderson’s writings on imagined communities, and H. L. Goodall’s methodology for the new ethnography the aim of this thesis is to fill in some small way this discursive and scholarly gap. The analysis of performances of the Mormon belief system through these lenses provides an insight into how the media teaches and shapes its audience’s ideologies through performance. iv For Caity and Emily. -

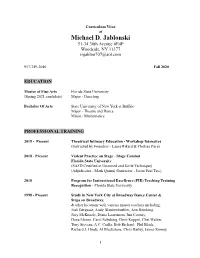

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. -

Onsale-Record-Release-Feb2016

PRESS RELEASE Friday 12 February 2016 MORMON BREAKS BOX-OFFICE RECORDS Less than a week after the Australian production of The Book of Mormon went on sale to the general public it has already entered the record books. The Tony®, Olivier®, and Grammy® award-winning musical has broken the house record at Melbourne’s Princess Theatre for the highest selling on sale period of any production in the theatre’s 159-year history. Written by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone and Avenue Q and Frozen co-creator Robert Lopez, Melbourne performances begin on 18 January 2017. Tickets officially went on sale to the general public at 9am Monday. The Australian season follows successful missions overseas where The Book of Mormon has played 253 consecutive weeks at more than 100% capacity on Broadway, 170 weeks at more than 100% capacity at theatres around the US, and sold out every single one of its 1228 performances thus far in London’s West End. “The best musical of this century.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times Winner of nine Tony Awards® including Best Musical, the Grammy® for Best Musical Theatre album and four Olivier Awards® including Best New Musical, The Book of Mormon is about to celebrate five years on Broadway and three years in London. The show has set house records at 47 theaters around the US and broken the house record at New York’s Eugene O’Neill Theater more than 50 times. The London production broke box office records for the highest single day of sales in West End history.