(The Musical) Is Awesomely Lame | Culture | Religion Dispatches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Noteworthy Life of Howard Barnes at Village Theatre Encore

SEPTEMBER 2018 September 2018 Volume 18, No. 1 RECEIVINGBR STANDING OVATIONS AVO! & RAVE REVIEWS FROM PATIENTS · Sports Medicine · Foot & Ankle · Spine Surgery · Joint Replacement · Hand & Wrist · Surgery Center Paul Heppner President Board Certified Orthopedic Surgeons Mike Hathaway Vice President (425) 339-2433 Kajsa Puckett www.ebjproliancesurgeons.com Vice President, Marketing & Business Development Genay Genereux EAP 1_6 H template.indd 1 9/30/16 11:56 AM Accounting & Office Manager Production Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Jennifer Sugden Assistant Production Manager Ana Alvira, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Designers Sales Amelia Heppner, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Joey Chapman, Brieanna Hansen, Ann Manning, Wendy Pedersen Seattle Area Account Executives Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Marketing Shaun Swick Senior Designer & Digital Lead Ciara Caya Marketing Coordinator Encore Media Group Corporate Office 425 North 85th Street Seattle, WA 98103 p 800.308.2898 | 206.443.0445 f 206.443.1246 [email protected] www.encoremediagroup.com APPARITIONS Encore Arts Programs and Encore Stages are published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events & in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. All rights reserved. ©2018 Encore Media Group. Reproduction without SPELLBOUND written permission is prohibited. September 18 through November 18, 2018 Opening Reception September 21, 2018 6pm – 8pm, FREE Image: Marlene Seven Bremner. The Transfiguration of Thoth. Oil on canvas. 620 Market Street Kirkland, WA 98033 kirklandartscenter.org 2 VILLAGE THEATRE ROBB HUNT Executive Producer JERRY DIXON Artistic Director Book and Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Music by Michael Kooman Francis J. Gaudette Theatre Everett Performing Arts Center September 13 – October 21, 2018 October 26 – November 18, 2018 Director BRANDON IVIE Choreographer Music Director Scenic Designer AL BLACKSTONE R.J. -

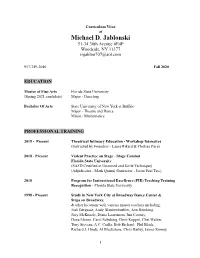

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. -

Teacher Resource Guide Falsettos.Titlepage.09272016 Title Page As of 091516.Qxd 9/27/16 1:51 PM Page 1

Teacher Resource Guide Falsettos.TitlePage.09272016_Title Page as of 091516.qxd 9/27/16 1:51 PM Page 1 Falsettos Teacher Resource Guide by Nicole Kempskie MJODPMO!DFOUFS!UIFBUFS André Bishop Producing Artistic Director Adam Siegel Hattie K. Jutagir Managing Director Executive Director of Development & Planning in association with Jujamcyn Theaters presents Music and Lyrics by William Finn Book by William Finn and James Lapine with (in alphabetical order) Stephanie J. Block Christian Borle Andrew Rannells Anthony Rosenthal Tracie Thoms Brandon Uranowitz Betsy Wolfe Sets Costumes Lighting Sound David Rockwell Jennifer Caprio Jeff Croiter Dan Moses Schreier Music Direction Orchestrations Vadim Feichtner Michael Starobin Casting Mindich Chair Tara Rubin, CSA Production Stage Manager Musical Theater Associate Producer Eric Woodall, CSA Scott Taylor Rollison Ira Weitzman General Manager Production Manager Director of Marketing General Press Agent Jessica Niebanck Paul Smithyman Linda Mason Ross Philip Rinaldi Choreography Spencer Liff Directed by James Lapine Lincoln Center Theater is grateful to the Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater at LCT for their leading support of this production. LCT also thanks these generous contributors to FALSETTOS: The SHS Foundation l The Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation The Kors Le Pere Foundation l Ted Snowdon The Ted and Mary Jo Shen Charitable Gift Fund American Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Center Theater. Playwrights Horizons, Inc., New York City, produced MARCH OF THE FALSETTOS Off-Broadway in 1981 and FALSETTOLAND Off-Broadway in 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE MUSICAL . 2 The Story . 2 The Characters . 4 The Writers . 5 Classroom Activities . -

S. Harrison 1 Trash Or Treasure in the Works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone

S. Harrison 1 Trash or Treasure in the Works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone: What’s the Difference, and Who Decides? On March 24, 2011, New York Times reporter Ben Brantley described The Book of Mormon as “the best musical of this century… Heaven on Broadway.” He praised the writers, producers, and actors for “achieving something like a miracle.” As if this weren’t enough, Brantley went on to describe the musical as “cathartic” and the characters as both “likeable and funny.” In an online video titled “Subversive, Satirical, and Sold Out” posted on June 10, 2012, 60 Minutes host Steve Kroft commends the musical, stating that tickets for The Book of Mormon were the most heartily sought and hardest to obtain on Broadway this past summer. Moreover, Kroft boasts of the creators’ “big heart” as the foundation of the musical’s success. To employ a simple Google search for The Book of Mormon – while oftentimes bringing up information on the actual book and its corresponding faith – is to call forth resounding reviews of praise from both professional and amateur critics. The performance is being described as witty and satirical, appealing to the vast majority of musical-goers. However, The Book of Mormon with its undeniable success calls forth questions and criticism prompted by the previous works of creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Parker and Stone are infamous for their roles as developers, producers of, and performers in South Park, a television show that, in the words of Kroft, “changed the face of cable television” with its lewd, scatological humor and sensitive (and correspondingly insensitive handling of) thematic elements. -

Than a Star's Sister

1E <pagelabeltag> The Palm Beach Post | Monday, September 10, 2012 See Winter the dolphin at the E Accent Clearwater Marine Aquarium Culture Editor: Larry Aydlette (561) 820-4436 [email protected] | On the web: palmbeachpost.com The Scene, 3E ‘I’m excited about the future. After all, life’s a journey.’ Cristiana Shields Gardens resident and jewelry designer More than a star’s sister Gardens resident Cristiana Shields has discovered her passion for life through jewelry design. ASSOCIATED PRESS PHOTO / NBC, TRAE PATTON Andrew Rannells as Bryan (left) and Justin Bartha as David in a scene from “The New Normal,” premiering at 9:30 p.m. Tuesday on NBC. Fathers know best? ‘New Normal’ more old-fashioned than you might think. By David Wiegand San Francisco Chronicle PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON NUTTLE, MAKE-UP BY MISH. JEWELRY BY SHIELDS JEWELRY. I wish I didn’t have to write Cristiana Shields at FUKU, a new restaurant opening on Clematis St. about what Ellen Barkin’s char- acter calls “the gay elephant in ByJanis Fontaine Brooke Shields All the pieces are handmade us- the room” in the new sitcom Palm Beach Post StaffWriter and her sister, ing stones she purchased from The New Normal, but since the Cristiana, are 10 all over the world. show was targeted by a conser- Cristiana Shields’ entrepre- years apart in “If I don’t like the person, vative moms group before any- neurial spirit showed up early. age. I don’t buy their stones,” she one saw it and has since been At age 7, she ran a successful said. -

The Book of Mormon

44 FGM Wednesday March 16 2011 | the times Times2 fashion Times2 arts The Squoom Perfector anti-ageing device costs £549; gadget fans Cameron South Park Diaz, Demi Moore and Courtney Cox; ‘‘ gadgetsfor couldn’t and the Clarisonic cleanser,£155 have your face survived withouta moral framework lifelongmusicals fan Parker,a“musical in the mosttraditional sense of the word. There are no special effects, we don’tmakeany grand claims to reinventingthe Broadway show and,” he adds earnestly,“it’s certainly not about hatingMormons.” ather likethe sandwich If the early audiences’ reaction is toaster, home beauty echoedbythe critics, The Bookof devices have oftenbeen Mormon —which Parker,41, and seen as gimmicky Stone, 39,wrote with RobertLopez, the innovations: funtouse co-writer/composer of Avenue Q — at firstbut all too maysoon supplant the crisis-beset quickly relegated to the Spider-Man: Turn offthe Dark as the R back of the cupboard. mosttalked-about show on Broadway, The pastyear,however,has seen a forthe best possible reasons. Stone boom in at-home beautytechnology solutions. While these so-called that it could also be usedinthe shower. Patrick Bowler doesn’tbelievethat the reveals that they hope to bringitto ledbyelectronic gadgets such as the “recessionista”gadgets vary in price — Afteraweek Ihad to admit that my success of the products will inhibit the London and to begin atouring TuaTre’nd (favouredbyKateMoss), from £150 to £300 —they help families skin certainly lookedbrighter,felt need to visit aspa. “The success of production in America. Slendertone’sFemale Face, and the whose budgets are being squeezed. The cleaner and wasverysofttothe touch. home technologyonly increasesour The show has so far met with nightly Clarisonic cleanser.This lastisthe backlashagainstBotox and invasive Face creams and masks seemedto awareness and desire forbetterskin. -

Hamilton: a Musical Analysis of Ensemble Function Matthew L

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-21-2017 Hamilton: A Musical Analysis of Ensemble Function Matthew L. Travis University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Travis, Matthew L., "Hamilton: A Musical Analysis of Ensemble Function" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1399. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1399 University of Connecticut DigitalCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-6-2017 Hamilton: A Musical Analysis of Ensemble Function Matthew L. Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Hamilton: A Musical Analysis of Ensemble Function Matthew Louis Travis, DMA The University of Connecticut, 2017 Abstract There have been exhaustive studies on the presence of chorus in opera, there has been little writing on the musical theater ensemble.1 To date, the only specific piece of academic scholarship on the matter is Joseph DeLorenzo’s 1985 dissertation, The Chorus in American Musical Theater: An Emphasis on Choral Performance. Because there are very few graduate programs in musical theater, and currently none at the doctoral level, there has been little scholarly writing about this art form as a whole and even less scholarship specific to ensemble function completed in the last 30 years. Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda is one of the most successful Broadway productions in recent memory. While the work has gained fame for unparalleled box office success and celebrity appearances; the show is equally significant as a work of art. Almost universally acclaimed by critics, Hamilton has won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Drama, while receiving a record 16 Tony nominations winning 11, winning the George Washington Book Prize and Kennedy Prize for Drama. -

HELLO BOYS! New York Audiences Are About to Rediscover Mart Crowley’S the Boys in the Band with an All-Gay, All-Star Revival

FEATURE THE REVIVAL CAST ZACHARY QUINTO, JIM PARSONS, MATT BOMER, CHARLIE CARVER, ROBIN DE JESUS, ANDREW RANNELLS, TUC WATKINS, MICHAEL BENJAMIN WASHINGTON AND BRIAN HUTCHISON. HELLO BOYS! New York audiences are about to rediscover Mart Crowley’s The Boys In The Band with an all-gay, all-star revival. Matt Myers previews this landmark production. LATELY, perhaps more than ever, the LGBTIQ world undergoing psychoanalysis. disco and de-criminalisation. But these characters is embracing its heritage. With the continuing Adding to the star power are Robin De Jesus are not unlike gay men of today. Zachary Quinto success of gay marriage laws around the world, (Camp) as Emory the so-called “flamer” of the believes their voices are still relevant. and with significant milestones such as the 50th group, Andrew Rannells (The New Normal) is the “We’ve come so far in the last five years, just anniversary of Stonewall next year and the recent bed-hopping Larry, and Tuc Watkins (Parks And legislatively,” he says. “And yet there’s been this 40th anniversary of the Sydney Mardi Gras, we seem Recreation) is his straight-laced boyfriend, Hank. explosion of backward, harmful thinking and to be re-discovering our past and acknowledging Michael Benjamin Washington (30 Rock) plays political ideology that’s swept our country. those who helped create it. African-American Bernard and Brian Hutchison “We are responsible for standing up and… Case in point, there’s been enthusiastic interest (Vinyl) is Alan, the straight, gatecrasher friend celebrating ourselves and celebrating our in the revival of the classic gay play, The Boys In with a secret. -

What Do Have in Common?

Night At This OutSeries Performance... What do F. Murray Abraham, Bea Arthur, Annaleigh Ashford, Armand Assante, Kate Baldwin, Roger Bart, Bryan Batt, Laura Benanti, Stephanie J. Block, Sierra Boggess, Christian Borle, Alex Brightman, Charl Brown, Laura Bell Bundy, Danny Burstein, Kerry Butler, Norbert Leo Butz, Liz Callaway, Michael Caine, Bobby Cannavale, Carolee Carmello, Keith Carradine, Kathleen Chalfant, Kevin Chamberlin, Carol Channing, Stockard Channing, Will Chase, Victoria Clark, Glenn Close, Chuck Cooper, Marilyn Cooper, Jon Cryer, John Cullum, Alan Cumming, Jeff Daniels, Blythe Danner, Ted Danson, Daniel Day-Lewis, Ruby Dee, Robin DeJesus, Danny DeVito, Taye Diggs, Laura Dreyfuss, Olympia Dukakis, Faye Dunaway, Charles Durning, Christine Ebersole, Gabriel Ebert, Mike Faist, Ralph Fiennes, Katie Finneran, Calista Flockhart, Barrett Foa, Santino Fontana, Hunter Foster, Sutton Foster, Beth Fowler, Morgan Freeman, Peter Gallagher, James Gandolfini, Jennifer Garner, Brad Garrett, Richard Gere, John Giulgud, Montego Glover, Jeff Goldblum, Louis Gossett Jr., Randy Graff, Kelsey Grammer, Ariana Grande, Frankie J. Grande, Jonathan Groff, Lena Hall, Michael C. Hall, Todrick Hall, Josh Hamilton, Valerie Harper, Woody Harrelson, Harriet Harris, Heather Headley, Joshua Henry, Megan Hilty, Dustin Hoffman, Anthony Hopkins, Dee Hoty, Cady Huffman, Anjelica Huston, Cheyenne Jackson, Christopher Jackson, Samuel L. Jackson, Brian d’Arcy James, Nikki M. James, Gregory Jbara, Nick Jonas, Rachel Bay Jones, Jeremy Jordan, Andy Karl, Judy Kaye, Steve Kazee, Diane Keaton, Celia Keenan-Bolger, Chad Kimball, Kevin Kline, Leslie Kritzer, Marc Kudish, Judy Kuhn, LaChanze, Annika Larsen, Dick Latessa, Linda Lavin, Cloris Leachman, Beth Leavel, Adrianne Lenox, Judith Light, Rebecca Luker, Shirley MacLaine, William H. Macy, Madonna, Billy Magnussen, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Terrence Mann, Walter Matthau, Jan Maxwell, Marin Mazzie, Frances McDormand, Michael McGrath, S. -

Star Channels, Jan. 20-26

JANUARY 20 - 26, 2019 staradvertiser.com CRASH-AMUNDO Black Monday is a fi ctionalized tale of the infamous 1987 stock market crash of the same name, and the characters and shenanigans that caused it. The show features a powerful cast led by Don Cheadle, and tells the story of a group of outsiders who shoulder their way into Wall Street’s realm of high fi nance, and ultimately contribute to the devastating market decline of October 1987. Premiering Sunday, Jan. 20, on Showtime. WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss upcoming legislation and issues of importance to the community. TUESDAY, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 olelo.org ON THE COVER | BLACK MONDAY Fall Street Showtime offers a darkly comic look The tone of “Black Monday” might surprise gentrified in order to play better to tourists at the 1987 stock market crash anyone expecting a somber treatment of in the 1990s. The trailer glories in its period a historical event that caused real, lasting piece trappings, and the show is absolutely economic pain, but the series’ provenance worth checking out for the look and feel alone. By Kenneth Andeel explains its darkly comic take on the stock That said, there is a lot to be said for the other TV Media market disaster. “Black Monday” is execu- aspects of the series as well. As mentioned, the tive produced by a team that includes Seth cast is, like, radical, man. Cheadle has been one umbered among the worst stock mar- Rogen and his longtime creative partner Evan of Hollywood’s most consistently excellent per- ket crashes in history is the October Goldberg, a duo responsible for such absurdist formers for a long time now, turning in seemingly N1987 event that came to be known by comedies as “Superbad” (2007), “Pineapple effortless, deep and nuanced performances no the catchy, not-at-all-scary nickname “Black Express” (2008) and the ongoing comic book- matter what kind of script he’s handed. -

Mulder 1 George Mulder Richard Roland History of Musical Theatre

Mulder 1 George Mulder Richard Roland History of Musical Theatre 30 April 2020 LGBTQ+ Representation in the Broadway Musical Theatre is perceived to be an accepting space for people of all walks of life. It is debatably notorious for being the societal island of misfit toys. However, taking a closer look at the pieces which have been produced tells a bit of a different story. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, etc. (hereon LGBTQ+) people may only see a sliver of their community portrayed on the stage. This is especially true in musical theatre on Broadway. I believe that the norms regarding LGBTQ+ representation in musical theatre have wavered, yet ultimately broadened, throughout the last 40 years and I intend to prove it by looking historically and presently at LGBTQ+ roles and the actors who have played them. The shows I will be examining in depth are La Cage aux Folles, Falsettos, Rent, Kinky Boots, Fun Home, and The Prom. I will also allude to media in other forms such as film and television, as I believe these mediums are intersectional with entertainment- and therefore musical theatre- in the United States. One might question why it is important to have everybody represented on the stage. Frankly, this is a privileged perception of theatre, and ultimately art. Art serves many purposes, and one of them is to capture the culture in which it is created. We have a history of looking to art for cultural context and explanations of facts. Over the last few decades, the Broadway musical has not particularly captured the culture in which it was created. -

{Download PDF} the Boys in the Band

THE BOYS IN THE BAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mart Crowley | 114 pages | 03 Dec 2010 | Samuel French Inc | 9780573640049 | English | Hollywood, CA, United States The Boys in the Band PDF Book Technical Specs. Just finished watching this new Netflix film and must comment on the terrific casting and production-the clothing and set design were as "spot on" as possible, but more importantly the acting was superb. User Reviews. Hot Property. Pedestrian uncredited Scott Eliasoph Want to watch. Right from the outset, it's very clear that there is a lot of hate in The Boys in the Band. Hank Brian Dole Catholic Priest uncredited. The Boys in the Band is about the cost of rejecting people, the dangers of what that sort of enforced captivity or identity suppression at the very least and performative "fitting in" can be, and the value of progress away from that. An interactive special. Leeza Gibbons. Runtime: 22 min. Genres: Comedy. Here we have a picture of a group of gay men who had to depend on each other for emotional and physical safety. Nominated for 1 Golden Globe. Written by Mart Crowley who died earlier this year , the original production and movie captured the then-shocking voices of a group of gay men in New York, written in the era before the Stonewall Riots and the greater activism and visibility that followed. If an audience is uncomfortable with the sight of the effeminate Emory or appalled by the promiscuity of Larry and Michael and Harold's razor-sharp bitching or the limited intelligence but game sexuality of Cowboy, it's because somewhere, that audience has been told that those stereotypes are not acceptable.