Laboratory 2 Simple Transistor Amplifiers: Lecture 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

Power Electronics

Diodes and Transistors Semiconductors • Semiconductor devices are made of alternating layers of positively doped material (P) and negatively doped material (N). • Diodes are PN or NP, BJTs are PNP or NPN, IGBTs are PNPN. Other devices are more complex Diodes • A diode is a device which allows flow in one direction but not the other. • When conducting, the diodes create a voltage drop, kind of acting like a resistor • There are three main types of power diodes – Power Diode – Fast recovery diode – Schottky Diodes Power Diodes • Max properties: 1500V, 400A, 1kHz • Forward voltage drop of 0.7 V when on Diode circuit voltage measurements: (a) Forward biased. (b) Reverse biased. Fast Recovery Diodes • Max properties: similar to regular power diodes but recover time as low as 50ns • The following is a graph of a diode’s recovery time. trr is shorter for fast recovery diodes Schottky Diodes • Max properties: 400V, 400A • Very fast recovery time • Lower voltage drop when conducting than regular diodes • Ideal for high current low voltage applications Current vs Voltage Characteristics • All diodes have two main weaknesses – Leakage current when the diode is off. This is power loss – Voltage drop when the diode is conducting. This is directly converted to heat, i.e. power loss • Other problems to watch for: – Notice the reverse current in the recovery time graph. This can be limited through certain circuits. Ways Around Maximum Properties • To overcome maximum voltage, we can use the diodes in series. Here is a voltage sharing circuit • To overcome maximum current, we can use the diodes in parallel. -

Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab)

ECE 327: Electronic Devices and Circuits Laboratory I Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab) 1. Introduce bipolar junction transistors • “Transistor man” (from The Art of Electronics (2nd edition) by Horowitz and Hill) – Transistors are not “switches” – Base–emitter diode current sets collector–emitter resistance – Transistors are “dynamic resistors” (i.e., “transfer resistor”) – Act like closed switch in “saturation” mode – Act like open switch in “cutoff” mode – Act like current amplifier in “active” mode • Active-mode BJT model – Collector resistance is dynamically set so that collector current is β times base current – β is assumed to be very high (β ≈ 100–200 in this laboratory) – Under most conditions, base current is negligible, so collector and emitter current are equal – β ≈ hfe ≈ hFE – Good designs only depend on β being large – The active-mode model: ∗ Assumptions: · Must have vEC > 0.2 V (otherwise, in saturation) · Must have very low input impedance compared to βRE ∗ Consequences: · iB ≈ 0 · vE = vB ± 0.7 V · iC ≈ iE – Typically, use base and emitter voltages to find emitter current. Finish analysis by setting collector current equal to emitter current. • Symbols – Arrow represents base–emitter diode (i.e., emitter always has arrow) – npn transistor: Base–emitter diode is “not pointing in” – pnp transistor: Emitter–base diode “points in proudly” – See part pin-outs for easy wiring key • “Common” configurations: hold one terminal constant, vary a second, and use the third as output – common-collector ties collector -

ECE 255, MOSFET Basic Configurations

ECE 255, MOSFET Basic Configurations 8 March 2018 In this lecture, we will go back to Section 7.3, and the basic configurations of MOSFET amplifiers will be studied similar to that of BJT. Previously, it has been shown that with the transistor DC biased at the appropriate point (Q point or operating point), linear relations can be derived between the small voltage signal and current signal. We will continue this analysis with MOSFETs, starting with the common-source amplifier. 1 Common-Source (CS) Amplifier The common-source (CS) amplifier for MOSFET is the analogue of the common- emitter amplifier for BJT. Its popularity arises from its high gain, and that by cascading a number of them, larger amplification of the signal can be achieved. 1.1 Chararacteristic Parameters of the CS Amplifier Figure 1(a) shows the small-signal model for the common-source amplifier. Here, RD is considered part of the amplifier and is the resistance that one measures between the drain and the ground. The small-signal model can be replaced by its hybrid-π model as shown in Figure 1(b). Then the current induced in the output port is i = −gmvgs as indicated by the current source. Thus vo = −gmvgsRD (1.1) By inspection, one sees that Rin = 1; vi = vsig; vgs = vi (1.2) Thus the open-circuit voltage gain is vo Avo = = −gmRD (1.3) vi Printed on March 14, 2018 at 10 : 48: W.C. Chew and S.K. Gupta. 1 One can replace a linear circuit driven by a source by its Th´evenin equivalence. -

Basic DC Motor Circuits

Basic DC Motor Circuits Living with the Lab Gerald Recktenwald Portland State University [email protected] DC Motor Learning Objectives • Explain the role of a snubber diode • Describe how PWM controls DC motor speed • Implement a transistor circuit and Arduino program for PWM control of the DC motor • Use a potentiometer as input to a program that controls fan speed LWTL: DC Motor 2 What is a snubber diode and why should I care? Simplest DC Motor Circuit Connect the motor to a DC power supply Switch open Switch closed +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 4 Current continues after switch is opened Opening the switch does not immediately stop current in the motor windings. +5V – Inductive behavior of the I motor causes current to + continue to flow when the switch is opened suddenly. Charge builds up on what was the negative terminal of the motor. LWTL: DC Motor 5 Reverse current Charge build-up can cause damage +5V Reverse current surge – through the voltage supply I + Arc across the switch and discharge to ground LWTL: DC Motor 6 Motor Model Simple model of a DC motor: ❖ Windings have inductance and resistance ❖ Inductor stores electrical energy in the windings ❖ We need to provide a way to safely dissipate electrical energy when the switch is opened +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 7 Flyback diode or snubber diode Adding a diode in parallel with the motor provides a path for dissipation of stored energy when the switch is opened +5V – The flyback diode allows charge to dissipate + without arcing across the switch, or without flowing back to ground through the +5V voltage supply. -

6 Insulated-Gate Field-Effect Transistors

Chapter 6 INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS Contents 6.1 Introduction ......................................301 6.2 Depletion-type IGFETs ...............................302 6.3 Enhancement-type IGFETs – PENDING .....................311 6.4 Active-mode operation – PENDING .......................311 6.5 The common-source amplifier – PENDING ...................312 6.6 The common-drain amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.7 The common-gate amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.8 Biasing techniques – PENDING ..........................312 6.9 Transistor ratings and packages – PENDING .................312 6.10 IGFET quirks – PENDING .............................313 6.11 MESFETs – PENDING ................................313 6.12 IGBTs ..........................................313 *** INCOMPLETE *** 6.1 Introduction As was stated in the last chapter, there is more than one type of field-effect transistor. The junction field-effect transistor, or JFET, uses voltage applied across a reverse-biased PN junc- tion to control the width of that junction’s depletion region, which then controls the conduc- tivity of a semiconductor channel through which the controlled current moves. Another type of field-effect device – the insulated gate field-effect transistor, or IGFET – exploits a similar principle of a depletion region controlling conductivity through a semiconductor channel, but it differs primarily from the JFET in that there is no direct connection between the gate lead 301 302 CHAPTER 6. INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS and the semiconductor material itself. Rather, the gate lead is insulated from the transistor body by a thin barrier, hence the term insulated gate. This insulating barrier acts like the di- electric layer of a capacitor, and allows gate-to-source voltage to influence the depletion region electrostatically rather than by direct connection. In addition to a choice of N-channel versus P-channel design, IGFETs come in two major types: enhancement and depletion. -

Differential Amplifiers

www.getmyuni.com Operational Amplifiers: The operational amplifier is a direct-coupled high gain amplifier usable from 0 to over 1MH Z to which feedback is added to control its overall response characteristic i.e. gain and bandwidth. The op-amp exhibits the gain down to zero frequency. Such direct coupled (dc) amplifiers do not use blocking (coupling and by pass) capacitors since these would reduce the amplification to zero at zero frequency. Large by pass capacitors may be used but it is not possible to fabricate large capacitors on a IC chip. The capacitors fabricated are usually less than 20 pf. Transistor, diodes and resistors are also fabricated on the same chip. Differential Amplifiers: Differential amplifier is a basic building block of an op-amp. The function of a differential amplifier is to amplify the difference between two input signals. How the differential amplifier is developed? Let us consider two emitter-biased circuits as shown in fig. 1. Fig. 1 The two transistors Q1 and Q2 have identical characteristics. The resistances of the circuits are equal, i.e. RE1 = R E2, RC1 = R C2 and the magnitude of +VCC is equal to the magnitude of �VEE. These voltages are measured with respect to ground. To make a differential amplifier, the two circuits are connected as shown in fig. 1. The two +VCC and �VEE supply terminals are made common because they are same. The two emitters are also connected and the parallel combination of RE1 and RE2 is replaced by a resistance RE. The two input signals v1 & v2 are applied at the base of Q1 and at the base of Q2. -

INA106: Precision Gain = 10 Differential Amplifier Datasheet

INA106 IN A1 06 IN A106 SBOS152A – AUGUST 1987 – REVISED OCTOBER 2003 Precision Gain = 10 DIFFERENTIAL AMPLIFIER FEATURES APPLICATIONS ● ACCURATE GAIN: ±0.025% max ● G = 10 DIFFERENTIAL AMPLIFIER ● HIGH COMMON-MODE REJECTION: 86dB min ● G = +10 AMPLIFIER ● NONLINEARITY: 0.001% max ● G = –10 AMPLIFIER ● EASY TO USE ● G = +11 AMPLIFIER ● PLASTIC 8-PIN DIP, SO-8 SOIC ● INSTRUMENTATION AMPLIFIER PACKAGES DESCRIPTION R1 R2 10kΩ 100kΩ 2 5 The INA106 is a monolithic Gain = 10 differential amplifier –In Sense consisting of a precision op amp and on-chip metal film 7 resistors. The resistors are laser trimmed for accurate gain V+ and high common-mode rejection. Excellent TCR tracking 6 of the resistors maintains gain accuracy and common-mode Output rejection over temperature. 4 V– The differential amplifier is the foundation of many com- R3 R4 10kΩ 100kΩ monly used circuits. The INA106 provides this precision 3 1 circuit function without using an expensive resistor network. +In Reference The INA106 is available in 8-pin plastic DIP and SO-8 surface-mount packages. Please be aware that an important notice concerning availability, standard warranty, and use in critical applications of Texas Instruments semiconductor products and disclaimers thereto appears at the end of this data sheet. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. PRODUCTION DATA information is current as of publication date. Copyright © 1987-2003, Texas Instruments Incorporated Products conform to specifications per the terms of Texas Instruments standard warranty. Production processing does not necessarily include testing of all parameters. www.ti.com SPECIFICATIONS ELECTRICAL ° ± At +25 C, VS = 15V, unless otherwise specified. -

Building a Vacuum Tube Amplifier

Brian Large Physics 398 EMI Final Report Building a Vacuum Tube Amplifier First, let me preface this paper by saying that I will try to write it for the idiot, because I knew absolutely nothing about amplifiers before I started. Project Selection I had tried putting together a stomp box once before (in high school), with little success, so the idea of building something as a project for this course intrigued me. I also was intrigued with building an amplifier because it is the part of the sound creation process that I understand the least. Maybe that’s why I’m not an electrical engineer. Anyways, I already own a solid-state amplifier (a Fender Deluxe 112 Plus), so I decided that it would be nice to add a tube amp. I drew up a list of “Things I wanted in an Amplifier” and began to discuss the matters with the course instructor, Professor Steve Errede, and my lab TA, Dan Finkenstadt. I had decided I wanted a class AB push-pull amp putting out 10-20 Watts. I had decided against a reverb unit because it made the schematic much more complicated and would also cost more. With these decisions in mind, we decided that a Fender Tweed Deluxe would be the easiest to build that fit my needs. The Deluxe schematic that I built my amp off of was a 5E3, built by Fender from 1955-1960 (Figure 1). The reason we chose such an old amp is because they sound great and their schematics are considerably easier to build. -

The Designer's Guide to Instrumentation Amplifiers

A Designer’s Guide to Instrumentation Amplifiers 3 RD Edition www.analog.com/inamps A DESIGNER’S GUIDE TO INSTRUMENTATION AMPLIFIERS 3RD Edition by Charles Kitchin and Lew Counts i All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the copyright owner. Information furnished by Analog Devices, Inc. is believed to be accurate and reliable. However, no responsibility is assumed by Analog Devices, Inc. for its use. Analog Devices, Inc. makes no representation that the interconnec- tion of its circuits as described herein will not infringe on existing or future patent rights, nor do the descriptions contained herein imply the granting of licenses to make, use, or sell equipment constructed in accordance therewith. Specifications and prices are subject to change without notice. ©2006 Analog Devices, Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. G02678-15-9/06(B) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I—IN-AMP BASICS ...........................................................................................................1-1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................1-1 IN-AMPS vs. OP AMPS: WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCES? ..................................................................1-1 Signal Amplification and Common-Mode Rejection ...............................................................................1-1 Common-Mode Rejection: Op Amp vs. In-Amp .....................................................................................1-3 -

Eimac Care and Feeding of Tubes Part 3

SECTION 3 ELECTRICAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 3.1 CLASS OF OPERATION Most power grid tubes used in AF or RF amplifiers can be operated over a wide range of grid bias voltage (or in the case of grounded grid configuration, cathode bias voltage) as determined by specific performance requirements such as gain, linearity and efficiency. Changes in the bias voltage will vary the conduction angle (that being the portion of the 360° cycle of varying anode voltage during which anode current flows.) A useful system has been developed that identifies several common conditions of bias voltage (and resulting anode current conduction angle). The classifications thus assigned allow one to easily differentiate between the various operating conditions. Class A is generally considered to define a conduction angle of 360°, class B is a conduction angle of 180°, with class C less than 180° conduction angle. Class AB defines operation in the range between 180° and 360° of conduction. This class is further defined by using subscripts 1 and 2. Class AB1 has no grid current flow and class AB2 has some grid current flow during the anode conduction angle. Example Class AB2 operation - denotes an anode current conduction angle of 180° to 360° degrees and that grid current is flowing. The class of operation has nothing to do with whether a tube is grid- driven or cathode-driven. The magnitude of the grid bias voltage establishes the class of operation; the amount of drive voltage applied to the tube determines the actual conduction angle. The anode current conduction angle will determine to a great extent the overall anode efficiency. -

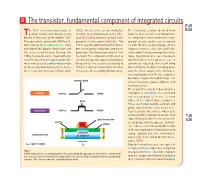

The Transistor, Fundamental Component of Integrated Circuits

D The transistor, fundamental component of integrated circuits he first transistor was made in (SiO2), which serves as an insulator. The transistor, a name derived from Tgermanium by John Bardeen and In 1958, Jack Kilby invented the inte- transfer and resistor, is a fundamen- Walter H. Brattain, in December 1947. grated circuit by manufacturing 5 com- tal component of microelectronic inte- The year after, along with William B. ponents on the same substrate. The grated circuits, and is set to remain Shockley at Bell Laboratories, they 1970s saw the advent of the first micro- so with the necessary changes at the developed the bipolar transistor and processor, produced by Intel and incor- nanoelectronics scale: also well-sui- the associated theory. During the porating 2,250 transistors, and the first ted to amplification, among other func- 1950s, transistors were made with sili- memory. The complexity of integrated tions, it performs one essential basic con (Si), which to this day remains the circuits has grown exponentially (dou- function which is to open or close a most widely-used semiconductor due bling every 2 to 3 years according to current as required, like a switching to the exceptional quality of the inter- “Moore's law”) as transistors continue device (Figure). Its basic working prin- face created by silicon and silicon oxide to become increasingly miniaturized. ciple therefore applies directly to pro- cessing binary code (0, the current is blocked, 1 it goes through) in logic cir- control gate cuits (inverters, gates, adders, and memory cells). The transistor, which is based on the switch source drain transport of electrons in a solid and not in a vacuum, as in the electron gate tubes of the old triodes, comprises three electrodes (anode, cathode and gate), two of which serve as an elec- transistor source drain tron reservoir: the source, which acts as the emitter filament of an electron gate insulator tube, the drain, which acts as the col- source lector plate, with the gate as “control- gate drain ler”.