ECE 255, MOSFET Basic Configurations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

Power Electronics

Diodes and Transistors Semiconductors • Semiconductor devices are made of alternating layers of positively doped material (P) and negatively doped material (N). • Diodes are PN or NP, BJTs are PNP or NPN, IGBTs are PNPN. Other devices are more complex Diodes • A diode is a device which allows flow in one direction but not the other. • When conducting, the diodes create a voltage drop, kind of acting like a resistor • There are three main types of power diodes – Power Diode – Fast recovery diode – Schottky Diodes Power Diodes • Max properties: 1500V, 400A, 1kHz • Forward voltage drop of 0.7 V when on Diode circuit voltage measurements: (a) Forward biased. (b) Reverse biased. Fast Recovery Diodes • Max properties: similar to regular power diodes but recover time as low as 50ns • The following is a graph of a diode’s recovery time. trr is shorter for fast recovery diodes Schottky Diodes • Max properties: 400V, 400A • Very fast recovery time • Lower voltage drop when conducting than regular diodes • Ideal for high current low voltage applications Current vs Voltage Characteristics • All diodes have two main weaknesses – Leakage current when the diode is off. This is power loss – Voltage drop when the diode is conducting. This is directly converted to heat, i.e. power loss • Other problems to watch for: – Notice the reverse current in the recovery time graph. This can be limited through certain circuits. Ways Around Maximum Properties • To overcome maximum voltage, we can use the diodes in series. Here is a voltage sharing circuit • To overcome maximum current, we can use the diodes in parallel. -

Common Drain - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07

Common drain - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07 Common drain From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In electronics, a common-drain amplifier, also known as a source follower, is one of three basic single- stage field effect transistor (FET) amplifier topologies, typically used as a voltage buffer. In this circuit the gate terminal of the transistor serves as the input, the source is the output, and the drain is common to both (input and output), hence its name. The analogous bipolar junction transistor circuit is the common- collector amplifier. In addition, this circuit is used to transform impedances. For example, the Thévenin resistance of a combination of a voltage follower driven by a voltage source with high Thévenin resistance is reduced to only the output resistance of the voltage follower, a small resistance. That resistance reduction makes the combination a more ideal voltage source. Conversely, a voltage follower inserted between a small load resistance and a driving stage presents an infinite load to the driving stage, an advantage in coupling a voltage signal to a small load. Characteristics At low frequencies, the source follower pictured at right has the following small signal characteristics.[1] Voltage gain: Current gain: Input impedance: Basic N-channel JFET source Output impedance: (the parallel notation indicates the impedance follower circuit (neglecting of components A and B that are connected in parallel) biasing details). The variable gm that is not listed in Figure 1 is the transconductance of the device (usually given in units of siemens). References http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_drain Page 1 of 2 Common drain - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07 1. -

Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab)

ECE 327: Electronic Devices and Circuits Laboratory I Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab) 1. Introduce bipolar junction transistors • “Transistor man” (from The Art of Electronics (2nd edition) by Horowitz and Hill) – Transistors are not “switches” – Base–emitter diode current sets collector–emitter resistance – Transistors are “dynamic resistors” (i.e., “transfer resistor”) – Act like closed switch in “saturation” mode – Act like open switch in “cutoff” mode – Act like current amplifier in “active” mode • Active-mode BJT model – Collector resistance is dynamically set so that collector current is β times base current – β is assumed to be very high (β ≈ 100–200 in this laboratory) – Under most conditions, base current is negligible, so collector and emitter current are equal – β ≈ hfe ≈ hFE – Good designs only depend on β being large – The active-mode model: ∗ Assumptions: · Must have vEC > 0.2 V (otherwise, in saturation) · Must have very low input impedance compared to βRE ∗ Consequences: · iB ≈ 0 · vE = vB ± 0.7 V · iC ≈ iE – Typically, use base and emitter voltages to find emitter current. Finish analysis by setting collector current equal to emitter current. • Symbols – Arrow represents base–emitter diode (i.e., emitter always has arrow) – npn transistor: Base–emitter diode is “not pointing in” – pnp transistor: Emitter–base diode “points in proudly” – See part pin-outs for easy wiring key • “Common” configurations: hold one terminal constant, vary a second, and use the third as output – common-collector ties collector -

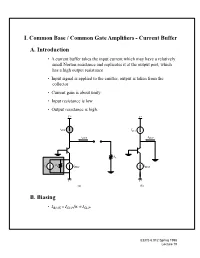

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers - Current Buffer A. Introduction • A current buffer takes the input current which may have a relatively small Norton resistance and replicates it at the output port, which has a high output resistance • Input signal is applied to the emitter, output is taken from the collector • Current gain is about unity • Input resistance is low • Output resistance is high. V+ V+ i SUP ISUP iOUT IOUT RL R is S IBIAS IBIAS V− V− (a) (b) B. Biasing = /α ≈ • IBIAS ISUP ISUP EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 II. Small Signal Two Port Parameters A. Common Base Current Gain Ai • Small-signal circuit; apply test current and measure the short circuit output current ib iout + = β v r gmv oib r − o ve roc it • Analysis -- see Chapter 8, pp. 507-509. • Result: –β ---------------o ≅ Ai = β – 1 1 + o • Intuition: iout = ic = (- ie- ib ) = -it - ib and ib is small EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 B. Common Base Input Resistance Ri • Apply test current, with load resistor RL present at the output + v r gmv r − o roc RL + vt i − t • See pages 509-510 and note that the transconductance generator dominates which yields 1 Ri = ------ gm µ • A typical transconductance is around 4 mS, with IC = 100 A • Typical input resistance is 250 Ω -- very small, as desired for a current amplifier • Ri can be designed arbitrarily small, at the price of current (power dissipation) EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 C. Common-Base Output Resistance Ro • Apply test current with source resistance of input current source in place • Note roc as is in parallel with rest of circuit g v m ro + vt it r − oc − v r RS + • Analysis is on pp. -

6 Insulated-Gate Field-Effect Transistors

Chapter 6 INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS Contents 6.1 Introduction ......................................301 6.2 Depletion-type IGFETs ...............................302 6.3 Enhancement-type IGFETs – PENDING .....................311 6.4 Active-mode operation – PENDING .......................311 6.5 The common-source amplifier – PENDING ...................312 6.6 The common-drain amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.7 The common-gate amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.8 Biasing techniques – PENDING ..........................312 6.9 Transistor ratings and packages – PENDING .................312 6.10 IGFET quirks – PENDING .............................313 6.11 MESFETs – PENDING ................................313 6.12 IGBTs ..........................................313 *** INCOMPLETE *** 6.1 Introduction As was stated in the last chapter, there is more than one type of field-effect transistor. The junction field-effect transistor, or JFET, uses voltage applied across a reverse-biased PN junc- tion to control the width of that junction’s depletion region, which then controls the conduc- tivity of a semiconductor channel through which the controlled current moves. Another type of field-effect device – the insulated gate field-effect transistor, or IGFET – exploits a similar principle of a depletion region controlling conductivity through a semiconductor channel, but it differs primarily from the JFET in that there is no direct connection between the gate lead 301 302 CHAPTER 6. INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS and the semiconductor material itself. Rather, the gate lead is insulated from the transistor body by a thin barrier, hence the term insulated gate. This insulating barrier acts like the di- electric layer of a capacitor, and allows gate-to-source voltage to influence the depletion region electrostatically rather than by direct connection. In addition to a choice of N-channel versus P-channel design, IGFETs come in two major types: enhancement and depletion. -

JFE150 Ultra-Low Noise, Low Gate Current, Audio, N-Channel JFET Datasheet

JFE150 SLPS732 – JUNE 2021 JFE150 Ultra-Low Noise, Low Gate Current, Audio, N-Channel JFET 1 Features and yields excellent noise performance for currents from 50 μA to 20 mA. When biased at 5 mA, the • Ultra-low noise: device yields 0.8 nV/√Hz of input-referred noise, – Voltage noise: giving ultra-low noise performance with extremely high input impedance (> 1 TΩ). The JFE150 also • 0.8 nV/√Hz at 1 kHz, IDS = 5 mA features integrated diodes connected to separate • 0.9 nV/√Hz at 1 kHz, IDS = 2 mA – Current noise: 1.8 fA/√Hz at 1 kHz clamp nodes to provide protection without the addition • Low gate current: 10 pA (max) of high leakage, nonlinear external diodes. • Low input capacitance: 24 pF at VDS = 5 V The JFE150 can withstand a high drain-to-source • High gate-to-drain and gate-to-source breakdown voltage of 40-V, as well as gate-to-source and gate- voltage: –40 V to-drain voltages down to –40 V. The temperature • High transconductance: 68 mS range is specified from –40°C to +125°C. The device • Packages: Small SC70 and SOT-23 (Preview) is offered in 5-pin SOT-23 and SC-70 packages. 2 Applications Device Information • Microphone inputs PART NUMBER PACKAGE(1) BODY SIZE (NOM) • Hydrophones and marine equipment SOT-23 (5) - Preview 2.90 mm × 1.60 mm JFE150 • DJ controllers, mixers, and other DJ equipment SC-70 (5) 2.00 mm × 1.25 mm • Professional audio mixer or control surface • Guitar amplifier and other music instrument (1) For all available packages, see the package option addendum at the end of the data sheet. -

INA106: Precision Gain = 10 Differential Amplifier Datasheet

INA106 IN A1 06 IN A106 SBOS152A – AUGUST 1987 – REVISED OCTOBER 2003 Precision Gain = 10 DIFFERENTIAL AMPLIFIER FEATURES APPLICATIONS ● ACCURATE GAIN: ±0.025% max ● G = 10 DIFFERENTIAL AMPLIFIER ● HIGH COMMON-MODE REJECTION: 86dB min ● G = +10 AMPLIFIER ● NONLINEARITY: 0.001% max ● G = –10 AMPLIFIER ● EASY TO USE ● G = +11 AMPLIFIER ● PLASTIC 8-PIN DIP, SO-8 SOIC ● INSTRUMENTATION AMPLIFIER PACKAGES DESCRIPTION R1 R2 10kΩ 100kΩ 2 5 The INA106 is a monolithic Gain = 10 differential amplifier –In Sense consisting of a precision op amp and on-chip metal film 7 resistors. The resistors are laser trimmed for accurate gain V+ and high common-mode rejection. Excellent TCR tracking 6 of the resistors maintains gain accuracy and common-mode Output rejection over temperature. 4 V– The differential amplifier is the foundation of many com- R3 R4 10kΩ 100kΩ monly used circuits. The INA106 provides this precision 3 1 circuit function without using an expensive resistor network. +In Reference The INA106 is available in 8-pin plastic DIP and SO-8 surface-mount packages. Please be aware that an important notice concerning availability, standard warranty, and use in critical applications of Texas Instruments semiconductor products and disclaimers thereto appears at the end of this data sheet. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. PRODUCTION DATA information is current as of publication date. Copyright © 1987-2003, Texas Instruments Incorporated Products conform to specifications per the terms of Texas Instruments standard warranty. Production processing does not necessarily include testing of all parameters. www.ti.com SPECIFICATIONS ELECTRICAL ° ± At +25 C, VS = 15V, unless otherwise specified. -

First-Order Circuits

CHAPTER SIX FIRST-ORDER CIRCUITS Chapters 2 to 5 have been devoted exclusively to circuits made of resistors and independent sources. The resistors may contain two or more terminals and may be linear or nonlinear, time-varying or time-invariant. We have shown that these resistive circuits are always governed by algebraic equations. In this chapter, we introduce two new circuit elements, namely, two- terminal capacitors and inductors. We will see that these elements differ from resistors in a fundamental way: They are lossless, and therefore energy is not dissipated but merely stored in these elements. A circuit is said to be dynamic if it includes some capacitor(s) or some inductor(s) or both. In general, dynamic circuits are governed by differential equations. In this initial chapter on dynamic circuits, we consider the simplest subclass described by only one first-order differential equation-hence the name first-order circuits. They include all circuits containing one 2-terminal capacitor (or inductor), plus resistors and independent sources. The important concepts of initial state, equilibrium state, and time constant allow us to find the solution of any first-order linear time-invariant circuit driven by dc sources by inspection (Sec. 3.1). Students should master this material before plunging into the following sections where the inspection method is extended to include linear switching circuits in Sec. 4 and piecewise- linear circuits in Sec. 5. Here,-the important concept of a dynamic route plays a crucial role in the analysis of piecewise-linear circuits by inspection. l TWO-TERMINAL CAPACITORS AND INDUCTORS Many devices cannot be modeled accurately using only resistors. -

Basic Electrical Engineering

BASIC ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING V.HimaBindu V.V.S Madhuri Chandrashekar.D GOKARAJU RANGARAJU INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous) Index: 1. Syllabus……………………………………………….……….. .1 2. Ohm’s Law………………………………………….…………..3 3. KVL,KCL…………………………………………….……….. .4 4. Nodes,Branches& Loops…………………….……….………. 5 5. Series elements & Voltage Division………..………….……….6 6. Parallel elements & Current Division……………….………...7 7. Star-Delta transformation…………………………….………..8 8. Independent Sources …………………………………..……….9 9. Dependent sources……………………………………………12 10. Source Transformation:…………………………………….…13 11. Review of Complex Number…………………………………..16 12. Phasor Representation:………………….…………………….19 13. Phasor Relationship with a pure resistance……………..……23 14. Phasor Relationship with a pure inductance………………....24 15. Phasor Relationship with a pure capacitance………..……….25 16. Series and Parallel combinations of Inductors………….……30 17. Series and parallel connection of capacitors……………...…..32 18. Mesh Analysis…………………………………………………..34 19. Nodal Analysis……………………………………………….…37 20. Average, RMS values……………….……………………….....43 21. R-L Series Circuit……………………………………………...47 22. R-C Series circuit……………………………………………....50 23. R-L-C Series circuit…………………………………………....53 24. Real, reactive & Apparent Power…………………………….56 25. Power triangle……………………………………………….....61 26. Series Resonance……………………………………………….66 27. Parallel Resonance……………………………………………..69 28. Thevenin’s Theorem…………………………………………...72 29. Norton’s Theorem……………………………………………...75 30. Superposition Theorem………………………………………..79 31. -

Lecture 19 Common-Gate Stage

4/7/2008 Lecture 19 OUTLINE • Common‐gate stage • Source follower • Reading: Chap. 7.3‐7.4 EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 1Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley Common‐Gate Stage AvmD= gR • Common‐gate stage is similar to common‐base stage: a rise in input causes a rise in output. So the gain is positive. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 2Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley EE105 Fall 2007 1 4/7/2008 Signal Levels in CG Stage • In order to maintain M1 in saturation, the signal swing at Vout cannot fall below Vb‐VTH EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 3Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley I/O Impedances of CG Stage 1 R = in λ =0 RRout= D gm • The input and output impedances of CG stage are similar to those of CB stage. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 4Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley EE105 Fall 2007 2 4/7/2008 CG Stage with Source Resistance 1 g vv= m Xin1 + RS gm 1 vv g AgR==out x m vmD1 vvxin + RS gm R gR ==D mD 1 1+ gRmS + RS gm • When a source resistance is present, the voltage gain is equal to that of a CS stage with degeneration, only positive. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 5Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley Generalized CG Behavior Rgout= (1++g mrR O) S r O • When a gate resistance is present it does not affect the gain and I/O impedances since there is no potential drop across it (at low frequencies). • The output impedance of a CG stage with source resistance is identical to that of CS stage with degeneration. -

Transistor Basics

Transistor Basics: Collector The schematic representation of a transistor is shown to the left. Note the arrow pointing down towards the emitter. This signifies it's an NPN transistor (current flows in the direction of the arrow). See the Q1 datasheet at: www.fairchildsemi.com. Base 2N3904 A transistor is basically a current amplifier. Say we let 1mA flow into the base. We may get 100mA flowing into the collector. Note: The Emitter currents flowing into the base and collector exit through the emitter (the sum off all currents entering or leaving a node must equal zero). The gain of the transistor will be listed in the datasheet as either βDC or Hfe. The gain won't be identical even in transistors with the same part number. The gain also varies with the collector current and temperature. Because of this we will add a safety margin to all our base current calculations (i.e. if we think we need 2mA to turn on the switch we'll use 4mA just to make sure). Sample circuit and calculations (NPN transistor): Let's say we want to heat a block of metal. One way to do that is to connect a power resistor to the block and run current through the resistor. The resistor heats up and transfers some of the heat to the block of metal. We will use a transistor as a switch to control when the resistor is heating up and when it's cooling off (i.e. no current flowing in the resistor). In the circuit below R1 is the power resistor that is connected to the object to be heated.