Mid-Tier Transit and Urban Regeneration – Core Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Pay Boost for Our Bus Drivers

THE TWUWHEEL PRINT POST APPROVED – 602669 - 00431 www.twuwa.org Summer 2008 Official publication of the Transport Workers Union (WA Branch) ☎ 1800 657 477 Some of the happy troops at Path Transit’s Morley depot Big pay boost for our bus drivers In 1996 Richard Court’s Liberal many of their government perks and government privatised Perth’s It’s amazing what a working conditions. metropolitan bus service and in the process turned bus driving from a bit of unity will do The TWU – who until then had no good job into a bad one. bus drivers as members – was asked to pick up the pieces and put them Transit or Southern Coast Transit. The drivers either went to work for together again. The now defunct Perth Bus got into private bus companies or they found the act a few years later. other jobs. Restoring an army of Humpty Dumpty’s would have been easier – it The drivers were paid between Those who stuck with the buses has been a long and often frustratng $10.80 and $12.00 per hour and lost signed on at Swan Transit, Path task. FULL STORY INSIDE First cases go before Owner-Driver’s Tribunal TWU member claims he is owed $34,000 by two hirers TWU STATE SECRETARY JIM McGIVERON Reports Word is quickly spreading around that owner-drivers can now take complaints against hirers to a special tribunal. During November, the Road Freight Industry Tribunal heard its first cases. One of them involved eight truck operators who contract to Independent Grocers of Australia (IGA). -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to the land, water and community. We pay our Respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Cultures and Elders past, present and emerging. Cover: Sydney, New South Wales This page: Palm Island, Queensland At SeaLink we are dedicated to connecting people, linking communities, sharing experiences, and creating brilliant memories. SeaLink Travel Group 2 Key Results 22 Five Year Financial Highlights 3 Directors’ Report 23 Our Global Operations 4 Financial Report 28 Our Australian Operations 6 Auditor’s Report 75 Community and Sustainability 8 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 81 Chair Report 10 Remuneration Report 82 Review of Operations 12 ASX Additional Information 92 Revenue History 20 Corporate Governance 94 Adelaide, South Australia SEALINK TRAVEL GROUP SeaLink provides innovative SeaLink Travel Group is Australia’s and London underway, an electric bus largest land and marine tourism and trial currently operating in NSW, on and efficient transport public transport service provider with demand services in Sydney, and is part established international operations. of the world’s first hydrogen consortium, the H2OzBus Project. As well as solutions that link people and It is one of Australia’s most experienced operating an eco-tourism resort on and diverse multi-modal transport communities with places and the world heritage listed, Fraser Island businesses, boasting performance-driven and eco experiences -

'We Specialise in Franchising'

interview adam leishman One of 380 buses that Tower Transit Singapore will begin operating later his year ‘We specialise in franchising’ Adam Leishman talks about Tower Transit’s ambitions in Singapore, London and the rest of the UK 2016 will see the 30th If these powers are implemented it will be company as a “franchise specialist”. anniversary of bus a huge change for Britain’s bus sector. Despite The company is a spin-off from Transit deregulation - but will there their opposition to franchising, it seems Systems, a company which won its first tender be a 40th anniversary? For unlikely that the ‘big five’ groups that dominate for bus operation in Perth, Western Australia, the past three decades, the industry will disappear (they’re happy to in 1995. Today the company operates a fleet Robert Jack private operators have operate within the franchised environments of around 1,000 buses in Australia, with Managing Editor played the dominant role of London’s bus market, the railways and contracts across the country. Tower Transit in planning and providing local bus services elsewhere), but could this revolution open up is a separate business, although it does share in England (outside London), Scotland and the market to new entrants? some of the same shareholders as Transit Wales, with local authorities and passenger London-based Tower Transit is one of the Systems. Leishman is one of four Tower transport executives limited to procuring companies that is waiting for this opportunity Transit shareholders, along with chairman Neil ‘non-commercial’ services on the periphery. to emerge. And the group’s Australian chief Smith, who is a co-founder of Transit Systems. -

Australian Bus PANORAMA

1 Volume 29.6 ISSN 0817-0193 May-June 2014 $9.00 rrp Australian Bus PANORAMA Registered by Australia Post—Publication No. PP 349069/00039 IN THIS ISSUE: A CENTENARY OF BOLTONS COACH AND BODY BUILDING FROM 1888 TO 1989 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 2014 O’CONNELL’S OF OMEO ADELAIDE’S NEW CITYFREE SERVICE 2 Three examples of how the body styling of both J.W. Boltons and Boltons Ltd changed over the decades. TOP: The last body style to be produced for Transperth is shown on (702) a 1988 Renault PR180.2 artic seen loading in St Georges Tce on a wet July morning in 1996. (Geoff Foster) CENTRE: This 1967 Leyland Tiger Cub was MTT 756 but is seen in later ownership by Horizons West. Similar bodies were built on Leopard and Panther chassis (Geoff Foster) BOTTOM: This 1952 Leyland Royal Tiger was built by Boltons for Metro Buses as (106) and is now preserved. (Bruce Tilley) 3 AUSTRALIAN BUS PANORAMA Vol 29 .6 May-June 2014 $9.00 rrp CONTENTS 4 A Centenary of Boltons Coach and body building, 1888-1989 8 Victorian State Election 2014 11 O’Connells of Omeo 12 Adelaide’s New Cityfree Service 14 National News Roundup 29 Pictorials 27 Fleet News COVER PHOTO: In their guises of Boltons Ltd and J.W. Bolton, this company bodied many of Perth’s government buses from the 1940s to the late 1980s. One example from 1983 is MTT (419) a J.W. Bolton Mercedes 0305 with later style rounded front. This photo was one in a series of postcard pictures which could be purchased from the Metropolitan Transport Trust in the 1980s. -

02 Operational Report

18 PTA Annual Report / Operational Report 02 Operational Report Photo: Stephen Endicott, N&I The summary is broken down as follows: A 2016-17 • 2.1 Our services – fleet, patronage, reliability, summary of our capacity and key operational activities. • 2.2 Fares and other revenue – overview of performance revenue and expenditure. • 2.3 PTA in the community – our commitment in providing to providing satisfactory, safe, well- safe, customer- communicated and sustainable operations. • 2.4 Infrastructure delivery – planning, focussed, projects, maintenance, upgrades and asset management. integrated and • 2.5 Our people – overview of our workforce and our strategy for developing, attracting and efficient transport retaining employees. services. A detailed overview of our targets and performance is available in the key performance indicators. PTA Annual Report / Our Services 19 Within the fleet, 677 buses conform to Euro5 and 2.1 Our services Euro6 emission standards (46 per cent of the total), and 492 buses to Euro4 (33.5 per cent). The other 300 buses conform to Euro0 and 2.1.1 Metro (Transperth) Euro3. Transperth is the brand and operating name of Transperth buses covered 280 standard the public transport system in the greater Perth timetabled bus routes (plus 32 non-timetabled metropolitan area. special event routes), 297 school routes and 10 The Transperth system consists of a bus network, CAT (Central Area Transit) routes. On a typical a fully-electrified urban train system and a ferry weekday this involved operating 15,317 standard service. It is managed by our Transperth branch service trips, 298 school service trips and 981 and covers key functions such as system CAT service trips. -

ASX Announcement

ASXMedia Announcement SEALINK TRAVEL GROUP LIMITED Level 3, 26 Flinders Street Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Tel (08) 8202 8688 16 January 2020 www.sealinktravelgroup.com.au SEALINK COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF TRANSIT SYSTEMS GROUP SeaLink’s acquisition of Transit Systems Group was completed today Strategically compelling acquisition creating a leading Australian multi-modal transport provider, with established international operations in Singapore and United Kingdom Transit Systems Group is a highly scalable operating platform, with a strong track record of contract wins and renewals, and an experienced management team operating typically long- term, low-risk, CPI indexed government service contracts Current Transit Systems Group CEO, Clint Feuerherdt, has replaced Jeff Ellison as SeaLink Group CEO SeaLink Travel Group Limited (ASX:SLK) (“SeaLink”) today announced it has completed the acquisition of 100% of Transit Systems Pty Ltd, Tower Transit Group Ltd and their broader group of entities (including trusts) (together the “Transit Systems Group”), Australia’s largest private operator of metropolitan public bus services and an established international bus operator in London and Singapore (the ‘Acquisition’). The SeaLink Board is also pleased to announce that Clint Feuerherdt, the current Group CEO of Transit Systems Group, has replaced Jeff Ellison as SeaLink Group CEO, effective from today. Jeff has agreed to provide support to Clint to ensure a smooth transition of leadership by remaining as an executive director of SeaLink for a short period of time, following which he will remain on the SeaLink Board of Directors as a non-executive director to continue sharing his extensive tourism and transport experience and knowledge. In addition, Neil Smith, one of the founding shareholders and current Chairman of Transit Systems Group, has joined the SeaLink Board of Directors as a non-executive director from today. -

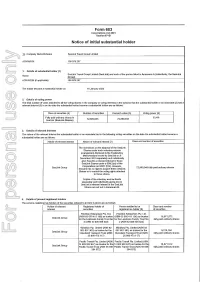

For Personal Use Only

Form 603 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671 B Notice of initial substantial holder To Company Mame/Scheme SeaLink Trave! Group Limited ACN/ARSM 109078257 1. Details of substantial holder (1) SeaLink TraveE Group Limited (SeaLink) and each of the parties iisted in Annexure A (co!lective1y, the SeaLink Name Group) ACN/ARSN(ifappiicable) 109 078 257 The holder became a substantial holder on 16 January 2020 2. Details of voting power The total number of votes attached to al! the voting shares in the company or voting interests in the scheme that the substantial holder or an associate (2) had a relevant interest (3) in on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Class of securities (4) Number of securities Person's votes (5) Voting power (6) Fuiiy paid ordinary shares in 33.4% SeaLink (SeaLink Shares) 72,569,945 72.869.945 3. Details of relevant interests substantiai holder are as follows: Holder of relevant interest Nature of relevant interest (7) Ciass and number of securities The restrictions on the disposal of the SeaLink Shares under each voluntary escrow arrangement disclosed in the Explanatory Memorandum issued by SeaUnk on 8 November 2019 ssparately and individuaSly give SeaLink a relevant interest in those Seai-ink Shares under s 608(1)(c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Ctti). However, SeaLink Group 72,869,945 fully paid ordinary shares SeaLink has no right to acquire these SeaLink Shares or to control the voting rights attached to those shares. Copies of the voluntary escrow deeds separately and individually giving rise to SeaLink's relevant interest in the SeaLink Shares are set out in Annexure B. -

The Transperth System

The Transperth system Transperth is the brand and operating name of the public transport system in metropolitan Perth, comprising of bus, train and ferry services. The Transperth system consists of: • a bus network providing services over 305 standard routes and 482 school service routes, operating a total fleet of 1,015 buses; • a suburban train network of 56 stations on four railway lines, 95 kilometres of track and a fleet of 48 two-car sets; and, • a ferry service using two vessels operating between the city (Barrack Street) and South Perth. Transperth bus and ferry services are provided under commercial contract arrangements, while Transperth train services are provided “in-house” by Transperth Train Operations. Currently three contractors provide bus services under eleven contracts: • Path Transit (Marmion-Wanneroo and Morley contracts); • Swan Transit (Canning, Kalamunda, Midland and Southern River contracts); • Swan Transit Riverside (Claremont-Belmont contract); and, • Southern Coast Transit (Rockingham-Mandurah, Fremantle-Cockburn, Perth Central Area Transit and Fremantle Central Area Transit contracts). Transperth ferry services are contracted to, and operated by, Captain Cook Cruises. The Transperth passenger information service is provided through information offices and a call centre, operated by a contracted service provider, Serco. Patronage Patronage on the Transperth system increased for the fifth year in succession. Total boardings, including free travel and transfers, increased by 2.8% from 88.1 million in 2002/03 to 90.6 million, while fare-paying initial boardings increased by 2.1% from 54.3 million to 55.5 million.The total capacity provided on the Transperth system, expressed in terms of passenger place kilometres, increased by 2.0% due mainly to the increase in the number of four-car train sets. -

Performance Measures Used in Transit Contracts: Review of Evidence

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Lake, Maree & Ferreira, Luis (2001) Performance measures used in transit contracts: Review of evidence. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/2498/ c Copyright 2001 (please consult author) This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Internal technical report Lake, M. and Ferreira, L. (2001) Performance measures used in transit contracts: Review of evidence . Technical Report TCRP Project G-6: ‘A Guidebook for Developing a Transit Performance-Measurement System’, Transportation Research Board and School of Civil Engineering, The US National Research Council and Queensland University of Technology. -

Annual Report 2011-12 Supporting Our Community Contents

Annual Report 2011-12 Supporting Our Community Contents Glossary of terms 2 PTA people 62 PTA year at a glance 3 Executive profiles 66 An introduction to your Annual Report 4 Compliance, audits and reporting 72 Organisational chart 7 Compliance statements 79 Cover Part of the PTA’s Overviews 8 Service and financial achievements 80 public art installation Chief Executive Officer 8 at Mount Lawley Managing Director 10 Electoral Act 1907 – Section 175ZE 88 Station. Transperth 12 Explanation of major capital expenditure variations 2011-12 90 Regional Town Bus Services 32 Independent audit opinion 92 School Bus Services 36 Audited Key Performance Indicators 94 Transwa 40 Financial statements 112 Network and Infrastructure 48 Certification of financial statements 113 Statement of comprehensive income 114 Major Projects Unit 52 Statement of financial position 115 Statement of changes in equity 116 Infrastructure Planning and Land Services 56 Statement of cash flows 117 Notes to the financial statements 118 Strategic Asset Management Development 60 To the Hon. Troy Buswell MLA Minister for Transport In accordance with Section 63 of the Financial Management Act 2006, I submit for your information and presentation to Parliament the Annual Report of the Public Transport Authority of Western Australia for the year ended 30 June 2012. The Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Financial Management Act 2006. Reece Waldock Chief Executive Officer 1 Glossary of terms AM Asset Management OTR On-time running Category B Incident that may have the potential to cause a serious accident. AMP Asset Management Plan PCL Perth City Link Circle A high-frequency bus service ASL Acceptable Service Level PMP Prevention Maintenance Program Route connecting major shopping centres, CAT Central Area Transit PPTA Perth Public Transport Area universities, schools and colleges. -

To View Submission from Principal Petitioner

,^:I' A , KENTRAVERSMLC is 16AUG2011 ^ 21129GRAND BOULEVARD (BEHINDANZBANK) 100NDALUPWA6027 ^nil. ^ Phone: (08) 9300 3422 "',!,, I"^.' Fax (08) 9300 3424 Hon Brian Ellis MLC Chairman Standing Committee on Environment and Public Affairs Parliament House PERTH WA 6000 DearCh I^;^ ,.,,,.., Petition N0 3.17- Trans errh Service Contracts- Re uest the re is Iative Council to investi ate the rocessfor awardin Government contracts . Ireferto your correspondence dated 30 May 2011 regarding the above petition, and am pleased to provide a submission in support of the petition. MY submission on this important issue is as follows. I am informed that the recent changes in Transperth Service Contracts has caused a great deal of concern and angst amongst bus operators. Contractsthat were previously held by Path Transit were changed over to Swan Transit (Marmion area) and SCr (Joondalup area), leaving bus operators in Joondalup, Karrinup, Nowergup and Warigara with new employers. This changeover constituted what I believe to be one of the most significant shake-ups in Transperth bus operations since privatisation in 1996. Prior to this year, each of the three private contractors serviced a large and roughly equal section of the Perth area. However, now that contracts have been taken away from Path Transit, I am made to understand that the economies of scale created by 'global running' will be lost, reducing efficiency and cutting the length of shift times for bus operators. o Employees who are now with new contractors will have new employment conditions and their accrued entitlements may be affected. MY understanding is that despite the magnitude of these changes, no consultation was done with bus operators. -

Neil Smith Biography 2012 Director Transit Systems

Neil Smith Biography 2012 Director Transit Systems www.transitsystems.com.au Neil Smith’s love of transport and what it offers communities drives him everyday, which is a passion that saw him send a letter of recommendations to the NSW Department of Government Transport when he was just 11 years old. Neil Smith’s official career in transport started years later as a trainee manager with the Busways Group in western Sydney in 1972, after obtaining a BA at the University of Sydney. In 1974 he formed a partnership that purchased Manly Bus Service in Sydney and 1975 he established Urban Transport Systems (UTS), offering consulting services in the areas of bus route design, bus and driver scheduling and public transport marketing. UTS worked with both the Macarthur Development Board and the private sector in the design and implementation of the improved bus services in Cambelltown, Blacktown, Cairns and the NSW Central Coast. Mr Smith was actively involved in the purchasing and operating of bus lines over the following years including Somersby Bus Lines, Central Coast Transit (renamed Peninsula Bus Lines), Davis Coach Lines and Roberts Brisbane Water Coaches and had an extensive involvement with the Bus & Coach Association (NSW), serving on the Executive Committee from 1983 to 1991. He was also involved with the establishment of the Certificate of Transport Management at the Institute of Transport Studies at the University of Sydney, and lectured in service design, marketing and Government relations. Between 1991 and 1994 Mr Smith moved away from operating services to complete a Masters of Transport Management at the University of Sydney.