Structural Patterns in Asante Kente : an Indigenous Instructional Resource for Design Education in Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meanings of Kente Cloth Among Self-Described American And

MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER (Under the Direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst) ABSTRACT Little has been published regarding people of African descent’s knowledge, interpretation, and use of African clothing. There is a large disconnect between members of the African Diaspora and African culture itself. The purpose of this exploratory study was to explore the use and knowledge of Ghana’s kente cloth by African and Caribbean and American college students of African descent. Two focus groups were held with 20 students who either identified as African, Caribbean, or African American. The data showed that students use kente cloth during some special occasions, although they have little knowledge of the history of kente cloth. This research could be expanded to include college students from other colleges and universities, as well as, students’ thoughts on African garments. INDEX WORDS: Kente cloth, African descent, African American dress, ethnology, Culture and personality, Socialization, Identity, Unity, Commencement, Qualitative method, Focus group, West Africa, Ghana, Asante, Ewe, Rite of passage MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT By MARISA SEKOLA TYLER B.S., North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 ©2016 Marisa Sekola Tyler All Rights Reserved MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICANS AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER Major Professor: Patricia Hunt-Hurst Committee: Tony Lowe Jan Hathcote Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv DEDICATION For Isaiah and Lydia. -

Symbolic Colors Found in African Kente Cloth (Grades K – 2)

Bold and beautiful: symbolic colors found in African Kente cloth (Grades K – 2) Procedure Introduction Have the students look closely at the clothes they are wearing, as well as any other fabrics in the classroom. Invite them to suggest how the fabrics might have been created: What materials and tools were used? Who might have made them? And so on. Ask whether fabrics and clothing are the same in other parts of the world, how they might be different, or why they may be different. Announce that they are going to learn about a very special type of fabric that was worn by kings in Africa, and point out Ghana on the map or globe in relation to the United States. The colors chosen for Kente cloths are symbolic, and a combination of colors come together to tell a story. For a full list of color symbol- ism, see background information (attached) Object-based Instruction Display the images. Guide the discussion using the following ques- tioning strategy, adapting it as desired. Include information about Kente cloth from the background material during the discussion. Akan peoples, Ghana, West Africa, Kente Cloth. Describe: What are we looking at? What colors and shapes do you see? How would you describe them? What kinds of lines are there? Time Analyze: What colors or shapes repeat? What are some patterns? 45 – 60 minutes Where do the patterns seem to change? How do you think this was made? Objectives Interpret: How do the colors in this cloth make you feel? Why do you think the weaver chose these colors? What other decisions did Students will identify, describe, create, and extend patterns using the weaver need to make while creating this piece of fabric? What lines, colors, and shapes, as they create Kente cloth designs. -

An Exploration of the Tourism Values of Northern Ghana. a Mini Review of Some Sacred Groves and Other Unique Sites

Journal of Tourism & Sports Management (JTSM) (ISSN:2642-021X) 2021 SciTech Central Inc., USA Vol. 4 (1) 568-586 AN EXPLORATION OF THE TOURISM VALUES OF NORTHERN GHANA. A MINI REVIEW OF SOME SACRED GROVES AND OTHER UNIQUE SITES Benjamin Makimilua Tiimub∗∗∗ College of Environmental and Resource Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China Isaac Baani Faculty of Environment and Health Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Ashanti Mampong Campus, Ghana Kwasi Obiri-Danso Office of the Former Vice Chancellor, Department of Theoretical and Applied Biology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology, Kumasi, Ghana Issahaku Abdul-Rahaman Desert Research Institute, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana Elisha Nyannube Tiimob Department of Transport, Faculty of Maritime Studies, Regional Maritime University, Nungua, Accra, Ghana Anita Bans-Akutey Faculty of Business Education, BlueCrest University College, Kokomlemle, Accra, Ghana Joan Jackline Agyenta Educational Expert in Higher Level Teacher Education, N.I.B. School, GES, Techiman, Bono East Region, Ghana Received 24 May 2021; Revised 12 June 2021; Accepted 14 June 2021 ABSTRACT Aside optimization of amateurism, scientific and cultural values, the tourism prospects of the 7 regions constituting Northern Ghana from literature review reveals that each area contains at least three unique sites. These sites offer various services which can be integrated ∗Correspondence to: Benjamin Makimilua Tiimub, College of Environmental and Resource Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, People’s Republic of China; Tel: 0086 182 58871677; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 568 Tiimub, Baani , Kwasi , Issahaku, Tiimob et al. into value chains for sustainable medium and long-term tourism development projects. -

An Investigation on the Role of Visual Merchandising Displays in the Promotion of Traditional Fabrics. an Evidence from Retailing the Asante Kente Fabrics in Ghana

Archives of Business Research – Vol.4, No.6 Publication Date: December. 25, 2016 DOI: 10.14738/abr.46.2571. Ofori-Okyere, I., & Kweku, S. A. (2016). An Investigation on the Role of Visual Merchandising Displays in the Promotion of Traditional Apparels. An Evidence from Retailing the Asante Kente Apparel in Ghana. Archives of Business Research, 4(6), 300-311. An investigation on the role of Visual Merchandising Displays in the promotion of traditional fabrics. An evidence from retailing the Asante Kente fabrics in Ghana. Isaac Ofori-Okyere Department of Marketing and Strategy Takoradi Technical University. Safo Ankama Kweku Department of Textiles Takoradi Technical University Abstract The fierce competition and the similarity of competing merchandise characterised modern fashion industry impel fabrics retailers to utilise various visual merchandising displays (VMDs) to improve the desirability of their products and to achieve differentiation of their offerings from competition. This has led to this study investigating on the role played by the various VMDs in the promotion of Asante Kente fabrics. Reviewed literature comprised: the Kente apparel, various VMDs adopted by retailers to promote products, and benefits derived by apparel retailers from adopting VMDs. An explorative research and qualitative data were gathered by means of projected images and focus groups discussions and direct observations. The data were analysed by means of thematic analysis. Findings indicated that respondents have knowledge on certain VMDs both exterior and in-store, whereas, other VMDs were considered not appropriate in their line of business. This is to say that all the respondents contacted on the field agreed to certain positions established by extant theories regarding the adoption of VMDs and the role they play in promoting apparels in retail shops Key Words: Kente fabrics and apparels, Visual MercHandising Displays, Ghana. -

Adire Cloth: Yoruba Art Textile

IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida Editor/Outreach Director: Agnes Ngoma Leslie Layout & Design: Pei Li Li Assisted by Kylene Petrin 427 Grinter Hall P.O. Box 115560 Gainesville, FL. 32611 (352) 392-2183, Fax: (352) 392-2435 Web: http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~outreach/ Center for African Studies Outreach Program at the University of Florida The Center is partly funded under the federal Title VI of the higher education act as a National Resource Center on Africa. As one of the major Resource Centers, Florida’s is the only center located in the Southeastern United States. The Center directs, develops and coordinates interdisci- plinary instruction, research and outreach on Africa. The Outreach Program includes a variety of activities whose objective is to improve the teaching of Africa in schools from K-12, colleges, universities and the community. Below are some of the regular activities, which fall under the Outreach Program. Teachers’ Workshops. The Center offers in- service workshops for K-12 teachers on the teaching of Africa. Summer Institutes. Each summer, the Center holds teaching institutes for K-12 teachers. Part of the Center’s mission is to promote Publications. The Center publishes teaching African culture. In this regard, it invites resources including Irohin, which is distributed to artists such as Dolly Rathebe, from South teachers. In addition, the Center has also pub- Africa to perform and speak in schools and lished a monograph entitled Lesson Plans on communities. -

The Fiber of Our Lives: a Conceptual Framework for Looking at Textilesâ

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2010 The Fiber of Our Lives: A Conceptual Framework for Looking at Textiles’ Meanings Beverly Gordon University of Wisconsin - Madison, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Gordon, Beverly, "The Fiber of Our Lives: A Conceptual Framework for Looking at Textiles’ Meanings" (2010). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE FIBER OF OUR LIVES: A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR LOOKING AT TEXTILES’ MEANINGS BEVERLY GORDON [email protected] I have been fascinated for decades with all of the meanings that fiber and cloth can hold—they are a universal part of human life, and fill an almost endless number of roles in our practical, personal, emotional, social, communicative, economic, aesthetic and spiritual lives. I have worked at finding meaningful ways to both explain textiles’ importance, and organize and synthesize the many disparate ideas that are part of this phenomenon. The following is the holistic framework or conceptual model I have developed that can be used to articulate and compare the meanings of textiles of any given culture or historic period. It is designed to be as inclusive as possible—to allow us to think about textiles and the roles they play in human consciousness and through the full range of human activities and concerns. -

Power Cloths of the Commonwealth

POWER CLOTHS OF THE COMMONWEALTH RMIT Victoria The Place To Be GALLERY Crafts Museum New Delhi India Australian Government 26 September -20 October ano Catalogue of Works A I C ARTS Government of South Australia Arts SA Dep ot of Fon¼o AffsInandt Trade VICTORIA 8 POWER CLOTHS Ls": St,'• -------- _ _ _ OF THE COMMONWEALTH m g Crafts Museum, New Delhi, India -,..- .-,....n.....-.: "C7 25 September —20 October 2010 -- rtr 'ft -t; - ; --- --- --- -4: T _ Curators: Suzanne Davies and jasleen Dhamija 0 ' • O.' NA, .0-•:\14<i ti . f ...,‘ \ .s4414. Presented in partnership by RMIT Gallery, 1rT 011% and the Crafts Museum, New Delhi, India. ___ ‘74..!oi"“ -s i ..i. Exhibition Advisory Committee, Delhi: 1. ..71 1‘,-) °•4# ‘.....7 • Not till ri .,,,, 40. Dr Ruchira Chose, Chairman, Crafts Museum; ProfessorJasleen Dharnija; Mr Ashok Dhawan; Mr Sudhakar Rao and Mrs Anita Saran --4•047 t Iv, \ • ' fa'N,\ • 4: ''llist, d .••••,, Research Assistant to Jasleen Dhamija: Ms Paroma Ghose k , i , ' vo, Exhibition Installation: Black Lines (4 '4, 1 RMIT GALLERY, MELBOURNE Director: Suzanne Davies Executive Assistant to Suzanne Davies: Vanessa Gerrans Exhibition Coordinator: Helen Rayment Conservators: Debra Spoehr and Sharon Towns Project Administration: Jon Buckingham ear 0 0 1\0 ' CRAFTS MUSEUM, NEW DELHI Chairman: Dr Ruchira Ghose Deputy Director: Dr Mushtalc Than e ri Deputy Director: Dr Chart; Sculta Gupta Mr S Ansari, Mr Bhittilal, Mrs S P Grover, Mr R L Karna, Mr MC Kaushik, Mr B B Meher, Mr Sahib Ram, Mr Nawab Singh, Mr Rajendra Singh, Mr Sunderlal -

Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: a Symbiosis of Factory-Made and Hand-Made Cloth

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth Heather Marie Akou Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Akou, Heather Marie, "Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 778. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/778 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth Heather Marie Akou Introduction The concepts of "tradition" and "fashion" both center on the idea of change. Fashion implies change, while tradition implies a lack of change. Many scholars have attempted to draw a line between the two, often with contradictory results. In a 1981 article titled, "Awareness: Requisite to Fashion," Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins argued that, If people in a society are generally not aware of change in form of dress during their lifetimes, fashion does not exist in that society. Awareness of change is a necessary condition for fashion to exist; the retrospective view of the historian does not produce fashion. I Although she praised an earlier scholar, Herbert Blumer, for promoting the serious study offashion2, their conceptualizations of the line between tradition and fashion differed. -

The Influence of European Elements on Asante Kente

International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) ISSN: 2394-4404 Volume 3 Issue 8, July 2016 The Influence Of European Elements On Asante Kente Dickson Adom Samuel Kissi Baah Hannah Serwaa Bonsu Lecturer, Department of Industrial Arts, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Department of General Art Studies, Kumasi, Ghana Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana Abstract: The Asante Kente has undergone several changes due to the impacts of some European elements. These impacts are greatly seen in the tools and materials, production techniques, as well as concepts or ideologies in the design of the Asante textiles. There are both merits and demerits of these impacts of the European elements. It appears that the impacts of these European elements on the Asante Kente have not been critically examined as to whether they are reflecting negatively or positively on the rich Kente heritage of the Asantes of Ghana. The study was therefore conducted to examine the impacts of the European elements so as to advise on what aspects of the European elements that needs to be discontinued and the aspects to be promoted. The researchers gathered data from primary and secondary sources by way of personal interviews, administration of questionnaires, as well as observation. The results of the study have been presented under the following headings: Analysis of the research instruments, main findings (primary and secondary data), Interpreting the data, answering of research questions, conclusions and recommendations. This involved investigating and examining the extent to which the Asante Kente have been impacted by these European elements, thus, the positive impacts and how they have ensured the improvement of the Asante textile industry and the negative impacts and how they have adversely affected the Asante Kente industry. -

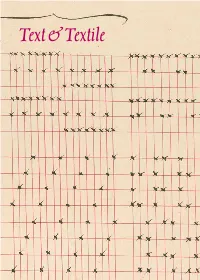

Text &Textile Text & Textile

1 TextText && TextileTextile 2 1 Text & Textile Kathryn James Curator of Early Modern Books & Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Melina Moe Research Affiliate, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Katie Trumpener Emily Sanford Professor of Comparative Literature and English, Yale University 3 May–12 August 2018 Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Yale University 4 Contents 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction Kathryn James 13 Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs, & the Finest Thread Melina Moe 31 Threads of Life: Textile Rituals & Independent Embroidery Katie Trumpener 51 A Thin Thread Kathryn James 63 Notes 67 Exhibition Checklist Fig. 1. Fabric sample (detail) from Die Indigosole auf dem Gebiete der Zeugdruckerei (Germany: IG Farben, between 1930 and 1939[?]). 2017 +304 6 Acknowledgments Then Pelle went to his other grandmother and said, Our thanks go to our colleagues in Yale “Granny dear, could you please spin this wool into University Library’s Special Collections yarn for me?” Conservation Department, who bring such Elsa Beskow, Pelle’s New Suit (1912) expertise and care to their work and from whom we learn so much. Particular thanks Like Pelle’s new suit, this exhibition is the work are due to Marie-France Lemay, Frances of many people. We would like to acknowl- Osugi, and Paula Zyats. We would like to edge the contributions of the many institu- thank the staff of the Beinecke’s Access tions and individuals who made Text and Textile Services Department and Digital Services possible. The Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Unit, and in particular Bob Halloran, Rebecca Center for British Art, and Manuscripts and Hirsch, and John Monahan, who so graciously Archives Department of the Yale University undertook the tremendous amount of work Library generously allowed us to borrow from that this exhibition required. -

The Textile Museum Thesaurus

The Textile Museum Thesaurus Edited by Cecilia Gunzburger TM logo The Textile Museum Washington, DC This publication and the work represented herein were made possible by the Cotsen Family Foundation. Indexed by Lydia Fraser Designed by Chaves Design Printed by McArdle Printing Company, Inc. Cover image: Copyright © 2005 The Textile Museum All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means -- electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise -- without the express written permission of The Textile Museum. ISBN 0-87405-028-6 The Textile Museum 2320 S Street NW Washington DC 20008 www.textilemuseum.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................vii How to Use this Document.........................................................................xiii Hierarchy Overview ....................................................................................... 1 Object Hierarchy............................................................................................ 3 Material Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 47 Structure Hierarchy ..................................................................................... 55 Technique Hierarchy .................................................................................. -

Armlet, 1500S, Made in the Benin

Man’s Cloth, c. 1920 –70, made by the Ewe or Adangme culture, Ghana or Togo Armlet, 1500s, made in the Benin Kingdom, Nigeria Compare and Connect • What are some similarities and differences between the patterns featured on the carved ivory armlet and the woven cotton cloth? • How does the material and process used in the making of these patterned artworks influence the final designs that we see? Education Are there certain patterns that are better suited for the surface of a cylinder of ivory versus a two-dimensional woven cloth? philamuseum.org/education • What are some things that an artist can do when working with ivory that can’t be done when working with textiles, and vice versa? About the Artwork Man’s Cloth About the Artwork Armlet c. 1920 –70 1500s Ewe (ay-vay) woven cloths are typically worn for This intricately carved armlet was made for an Oba (king) of the Benin Kingdom and is important events such as funerals, puberty rites, Strip-woven cotton plain an incredible example of the skill of ivory carvers of the 1500s. It was one of a pair that Ivory weddings, and in celebration of newborns. Cloths weave (warp-faced and would have been worn on special occasions. Decorated with a repeating pattern of men Size: 5 1/16 × 3 5/8 × 3 like this one are handmade, labor intensive, and balanced) with continuous with mudfish feet grabbing fierce crocodiles by the tails, the armlet was originally adorned 9/16 inches supplementary wefts and quite expensive. They serve as both status with metal decorations that fit into the rounded shield-like shapes that fall in between the (12.8 × 9.2 × 9 cm) weft-faced rib weave symbols and symbols of identity for wearers.