The Fiber of Our Lives: a Conceptual Framework for Looking at Textilesâ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hidden Bali Experiences Small-Group Tours That Touch the Heart of Bali

Hidden Bali Experiences small-group tours that touch the heart of Bali Our Hidden Bali Experiences can be arranged at any time to grant you access to authentic culture that honors tradition and avoids commoditization. Building on more than 20 years of experience of leading culturally sensitive tours in Bali and based on deep relationships with local people and communities, these are intimate 3-day or 4-day tours arranged to fit your travel itineraries and led by expert guides for small groups of 2 to 6 guests. Each experience is themed around a specific aspect of Bali’s heritage, including the Textile Arts, the Festival Cycle, the Performing Arts, and the Natural World. For more information on these Experiences, please visit our website at http://www.threadsoflife.com The Textile Arts Experience The Indonesian archipelago was once the crossroads of the world. For over 3500 years, people have come here seeking fragrant spices, and textiles were the central barter objects in this story of trade, conquest and ancient tradition. An exploration of Bali’s textile art traditions grants us access to this story. Spice trade influences juxtapose with indigenous motifs throughout the archipelago: echoes of Indian trade cloths abound; imagery relates to defining aspects of the local environment; history and genealogy entwine. Uses range from traditional dress, to offerings, to the paraphernalia of marriages and funerals. Our gateway to this world is through the island of Bali, where we steep ourselves in the island’s rich traditions while based at the Umajati Retreat near Ubud. Here we will receive insightful introductions to the local culture, and visit several weavers with which Threads of Life is working to help women create high-quality textiles that balance their desires for sustainable incomes and cultural integrity. -

Pergub DIY Tentang Penggunaan Pakaian Adat Jawa Bagi

SALINAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA PERATURAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA NOMOR 87 TAHUN 2014 TENTANG PENGGUNAAN PAKAIAN TRADISIONAL JAWA YOGYAKARTA BAGI PEGAWAI PADA HARI TERTENTU DI DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA, Menimbang : a. bahwa salah satu keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta sebagaimana ditetapkan dalam Pasal 7 ayat (2) Undang-undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2012 tentang Keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta adalah urusan kebudayaan yang perlu dilestarikan, dipromosikan antara lain dengan penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta; b. bahwa dalam rangka melestarikan, mempromosikan dan mengembangkan kebudayaan salah satunya melalui penggunaan busana tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta, maka perlu mengatur penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional pada hari tertentu di Lingkungan Pemerintah Daerah Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta; c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, huruf dan b perlu menetapkan Peraturan Gubernur tentang Penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta Bagi Pegawai Pada Hari Tertentu Di Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta; Mengingat : 1. Pasal 18 ayat (6) Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia 1945; 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Berita Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1950, Nomor 3) sebagaimana telah diubah terakhir dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 9 Tahun 1955 tentang Perubahan Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 1950 jo Nomor 19 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1955, Nomor 43, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 827); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2012 tentang Keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2012, Nomor 170, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5339); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 5 Tahun 2014 tentang Aparatur Sipil Negara (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2014 Nomor 6, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5494); 5. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Pullen, Lesley S. (2017) Representation of textiles on classical Javanese sculpture. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/26680 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Representation of Textiles on Classical Javanese Sculpture Volume 2 Appendices Lesley S Pullen Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2017 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology SOAS University of London 1 Table of Contents Appendix 1……………………………………………………………………………………..………….4 Catalogue of images and drawings textile patterns Appendix 2……………………………………………………………………..…………………………86 Plates of Drawings and textile patterns Appendix 3………………………………………………………………………………….…………….97 Plates of Comparative Textiles Appendix 4……………………………………….........................................................107 Maps 2 List of Figures Appendix 1……………………………………………………………………………………..………….4 -

Meanings of Kente Cloth Among Self-Described American And

MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER (Under the Direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst) ABSTRACT Little has been published regarding people of African descent’s knowledge, interpretation, and use of African clothing. There is a large disconnect between members of the African Diaspora and African culture itself. The purpose of this exploratory study was to explore the use and knowledge of Ghana’s kente cloth by African and Caribbean and American college students of African descent. Two focus groups were held with 20 students who either identified as African, Caribbean, or African American. The data showed that students use kente cloth during some special occasions, although they have little knowledge of the history of kente cloth. This research could be expanded to include college students from other colleges and universities, as well as, students’ thoughts on African garments. INDEX WORDS: Kente cloth, African descent, African American dress, ethnology, Culture and personality, Socialization, Identity, Unity, Commencement, Qualitative method, Focus group, West Africa, Ghana, Asante, Ewe, Rite of passage MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT By MARISA SEKOLA TYLER B.S., North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 ©2016 Marisa Sekola Tyler All Rights Reserved MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICANS AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER Major Professor: Patricia Hunt-Hurst Committee: Tony Lowe Jan Hathcote Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv DEDICATION For Isaiah and Lydia. -

Symbolic Colors Found in African Kente Cloth (Grades K – 2)

Bold and beautiful: symbolic colors found in African Kente cloth (Grades K – 2) Procedure Introduction Have the students look closely at the clothes they are wearing, as well as any other fabrics in the classroom. Invite them to suggest how the fabrics might have been created: What materials and tools were used? Who might have made them? And so on. Ask whether fabrics and clothing are the same in other parts of the world, how they might be different, or why they may be different. Announce that they are going to learn about a very special type of fabric that was worn by kings in Africa, and point out Ghana on the map or globe in relation to the United States. The colors chosen for Kente cloths are symbolic, and a combination of colors come together to tell a story. For a full list of color symbol- ism, see background information (attached) Object-based Instruction Display the images. Guide the discussion using the following ques- tioning strategy, adapting it as desired. Include information about Kente cloth from the background material during the discussion. Akan peoples, Ghana, West Africa, Kente Cloth. Describe: What are we looking at? What colors and shapes do you see? How would you describe them? What kinds of lines are there? Time Analyze: What colors or shapes repeat? What are some patterns? 45 – 60 minutes Where do the patterns seem to change? How do you think this was made? Objectives Interpret: How do the colors in this cloth make you feel? Why do you think the weaver chose these colors? What other decisions did Students will identify, describe, create, and extend patterns using the weaver need to make while creating this piece of fabric? What lines, colors, and shapes, as they create Kente cloth designs. -

Adire Cloth: Yoruba Art Textile

IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida Editor/Outreach Director: Agnes Ngoma Leslie Layout & Design: Pei Li Li Assisted by Kylene Petrin 427 Grinter Hall P.O. Box 115560 Gainesville, FL. 32611 (352) 392-2183, Fax: (352) 392-2435 Web: http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~outreach/ Center for African Studies Outreach Program at the University of Florida The Center is partly funded under the federal Title VI of the higher education act as a National Resource Center on Africa. As one of the major Resource Centers, Florida’s is the only center located in the Southeastern United States. The Center directs, develops and coordinates interdisci- plinary instruction, research and outreach on Africa. The Outreach Program includes a variety of activities whose objective is to improve the teaching of Africa in schools from K-12, colleges, universities and the community. Below are some of the regular activities, which fall under the Outreach Program. Teachers’ Workshops. The Center offers in- service workshops for K-12 teachers on the teaching of Africa. Summer Institutes. Each summer, the Center holds teaching institutes for K-12 teachers. Part of the Center’s mission is to promote Publications. The Center publishes teaching African culture. In this regard, it invites resources including Irohin, which is distributed to artists such as Dolly Rathebe, from South teachers. In addition, the Center has also pub- Africa to perform and speak in schools and lished a monograph entitled Lesson Plans on communities. -

The Aichhorn Collection

SAMMLUNG AICHHORN THE AICHHORN COLLECTION BAND 1 VOLUME 1 IKAT Impressum Imprint Bibliograische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek IKAT – The Aichhorn Collection is listed in the Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation German National Bibliography; detailed bibliographic in der Deutschen Nationalbibliograie; detaillierte bibliograische Daten data can be viewed at http://dnb.d-nb.de. sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ©2016 Verlag Anton Pustet ©2016 Verlag Anton Pustet 5020 Salzburg, Bergstrasse 12 5020 Salzburg, Bergstraße 12 All rights reserved. Sämtliche Rechte vorbehalten. Photographs: Ferdinand Aichhorn Fotos: Ferdinand Aichhorn Translation: Gail Schamberger Graik, Satz und Produktion: Tanja Kühnel Production: Tanja Kühnel Lektorat: Anja Zachhuber, Tanja Kühnel Proofreading: Anja Zachhuber Druck: Druckerei Samson, St. Margarethen Printing: Druckerei Samson, St. Margarethen Gedruckt in Österreich Printed in Austria 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 20 19 18 17 16 20 19 18 17 16 ISBN 978-3-7025-0826-5 ISBN 978-3-7025-0826-5 www.pustet.at www.pustet.at Inhaltsverzeichnis Table of Contents 6 Vorwort 6 Preface 8 Indonesien 8 Indonesia 11 Bali 11 Bali 15 Sumatra 15 Sumatra 17 Flores 17 Flores 33 Sumba 33 Sumba 43 Sulawesi 43 Sulawesi 46 Indien 46 India 48 Gujarat 48 Gujarat 59 Andhra Pradesh 59 Andhra Pradesh 81 Odisha 81 Odisha 116 Kambodscha 116 Cambodia 126 Thailand 126 Thailand 132 Burma 132 Burma 146 Iran/Usbekistan 146 Iran/Uzbekistan 166 Glossar 166 Glossary 166 Literaturverzeichnis 166 Bibliography VORWORT Meine Leidenschaft für asiatische Textilien begann 1977 mit Inseln zu besuchen. Dann hörte ich, dass auch in Indien, ins- dem Geringsing. -

Caadfutures- Pebryani-Kleiss Edit5

Ethno-Computation: Culturally Specific Design Application of Geringsing Textile Patterns Nyoman Dewi Pebryani 1, Michael C.B. Kleiss 2 1 Clemson University [email protected] 1 Indonesia Institute of The Arts (ISI) Denpasar [email protected] 2 Clemson University [email protected] Abstract. This study focuses on (1) understanding the indigenous algorithm of specific material culture named Geringsing textile patterns, and then (2) transforming the indigenous algorithm into an application that best serves local artisans and younger generation as a design tool and educational tool. Patterns design, which is created in textile as a material culture from a specific area, has a unique design grammar. Geringsing textile is unique to this part of the world because it is produced with double-ikat weaving technique, and this technique is only used in three places in the world. This material culture passes from generation to generation as an oral tradition. To safeguard, document, and digitize this knowledge, a sequential research methodology of ethnography and computation is employed in this study to understand the indigenous algorithm of Geringsing textile patterns, and then to translate the algorithm with computer simulation. This culturally specific design application then is tested by two local artisans and two aspiring artists from the younger generations in the village to see whether this application can serve as a design and educational tool. Keywords: Ethno-Computation, Culturally specific, Indigenous algorithm, Geringsing. 1 Introduction Material culture refers to the physical objects, resources, and spaces that people use to define their culture, therefore material culture is produced based on the cultural knowledge owned by the local people in a specific area. -

Power Cloths of the Commonwealth

POWER CLOTHS OF THE COMMONWEALTH RMIT Victoria The Place To Be GALLERY Crafts Museum New Delhi India Australian Government 26 September -20 October ano Catalogue of Works A I C ARTS Government of South Australia Arts SA Dep ot of Fon¼o AffsInandt Trade VICTORIA 8 POWER CLOTHS Ls": St,'• -------- _ _ _ OF THE COMMONWEALTH m g Crafts Museum, New Delhi, India -,..- .-,....n.....-.: "C7 25 September —20 October 2010 -- rtr 'ft -t; - ; --- --- --- -4: T _ Curators: Suzanne Davies and jasleen Dhamija 0 ' • O.' NA, .0-•:\14<i ti . f ...,‘ \ .s4414. Presented in partnership by RMIT Gallery, 1rT 011% and the Crafts Museum, New Delhi, India. ___ ‘74..!oi"“ -s i ..i. Exhibition Advisory Committee, Delhi: 1. ..71 1‘,-) °•4# ‘.....7 • Not till ri .,,,, 40. Dr Ruchira Chose, Chairman, Crafts Museum; ProfessorJasleen Dharnija; Mr Ashok Dhawan; Mr Sudhakar Rao and Mrs Anita Saran --4•047 t Iv, \ • ' fa'N,\ • 4: ''llist, d .••••,, Research Assistant to Jasleen Dhamija: Ms Paroma Ghose k , i , ' vo, Exhibition Installation: Black Lines (4 '4, 1 RMIT GALLERY, MELBOURNE Director: Suzanne Davies Executive Assistant to Suzanne Davies: Vanessa Gerrans Exhibition Coordinator: Helen Rayment Conservators: Debra Spoehr and Sharon Towns Project Administration: Jon Buckingham ear 0 0 1\0 ' CRAFTS MUSEUM, NEW DELHI Chairman: Dr Ruchira Ghose Deputy Director: Dr Mushtalc Than e ri Deputy Director: Dr Chart; Sculta Gupta Mr S Ansari, Mr Bhittilal, Mrs S P Grover, Mr R L Karna, Mr MC Kaushik, Mr B B Meher, Mr Sahib Ram, Mr Nawab Singh, Mr Rajendra Singh, Mr Sunderlal -

Les Textiles Patola De Patan ( Inde), Xviie Et Xxie Siècles : Techniques, Patrimoine, Mémoire Manisha Iyer

Les textiles patola de Patan ( Inde), XVIIe et XXIe siècles : techniques, patrimoine, mémoire Manisha Iyer To cite this version: Manisha Iyer. Les textiles patola de Patan ( Inde), XVIIe et XXIe siècles : techniques, patrimoine, mémoire. Histoire. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne - Paris I, 2015. Français. NNT : 2015PA010653. tel-02494004 HAL Id: tel-02494004 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02494004 Submitted on 28 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Ecole doctorale d’histoire (ED113) Centre d’histoire des techniques (IHMC « Institut d’histoire moderne et contemporaine) Doctorat en histoire moderne Manisha Iyer Les textiles patola de Patan (Inde), XVIIe et XXIe siècles: techniques, patrimoine, mémoire Thèse dirigée par Madame Anne-Françoise Garçon, professeur Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Date de soutenance : le 2 décembre 2015 Pré-rapporteurs : Filipe Themudo Barata, professeur, Université d’Evora Pierre Lamard, professeur des Universités (72ème section de CNU) Membres du jury : Sophie Desrosiers, Maître de conférences, EHESS Michel Cotte, professeur émérite, Université de Nantes Lotika Varadarajan, Tagore Fellow, National Museum de New Delhi Anne-Françoise Garçon, professeur des Universités, Université de Paris1 Panthéon Sorbonne REMERCIEMENTS En premier lieu, je souhaite remercier chaleureusement Prof. -

Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: a Symbiosis of Factory-Made and Hand-Made Cloth

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth Heather Marie Akou Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Akou, Heather Marie, "Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 778. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/778 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cloth in Contemporary West Africa: A Symbiosis of Factory-made and Hand-made Cloth Heather Marie Akou Introduction The concepts of "tradition" and "fashion" both center on the idea of change. Fashion implies change, while tradition implies a lack of change. Many scholars have attempted to draw a line between the two, often with contradictory results. In a 1981 article titled, "Awareness: Requisite to Fashion," Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins argued that, If people in a society are generally not aware of change in form of dress during their lifetimes, fashion does not exist in that society. Awareness of change is a necessary condition for fashion to exist; the retrospective view of the historian does not produce fashion. I Although she praised an earlier scholar, Herbert Blumer, for promoting the serious study offashion2, their conceptualizations of the line between tradition and fashion differed. -

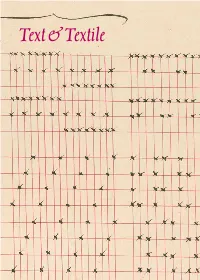

Text &Textile Text & Textile

1 TextText && TextileTextile 2 1 Text & Textile Kathryn James Curator of Early Modern Books & Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Melina Moe Research Affiliate, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Katie Trumpener Emily Sanford Professor of Comparative Literature and English, Yale University 3 May–12 August 2018 Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Yale University 4 Contents 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction Kathryn James 13 Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs, & the Finest Thread Melina Moe 31 Threads of Life: Textile Rituals & Independent Embroidery Katie Trumpener 51 A Thin Thread Kathryn James 63 Notes 67 Exhibition Checklist Fig. 1. Fabric sample (detail) from Die Indigosole auf dem Gebiete der Zeugdruckerei (Germany: IG Farben, between 1930 and 1939[?]). 2017 +304 6 Acknowledgments Then Pelle went to his other grandmother and said, Our thanks go to our colleagues in Yale “Granny dear, could you please spin this wool into University Library’s Special Collections yarn for me?” Conservation Department, who bring such Elsa Beskow, Pelle’s New Suit (1912) expertise and care to their work and from whom we learn so much. Particular thanks Like Pelle’s new suit, this exhibition is the work are due to Marie-France Lemay, Frances of many people. We would like to acknowl- Osugi, and Paula Zyats. We would like to edge the contributions of the many institu- thank the staff of the Beinecke’s Access tions and individuals who made Text and Textile Services Department and Digital Services possible. The Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Unit, and in particular Bob Halloran, Rebecca Center for British Art, and Manuscripts and Hirsch, and John Monahan, who so graciously Archives Department of the Yale University undertook the tremendous amount of work Library generously allowed us to borrow from that this exhibition required.