Textiles in Contemporary Art, November 8, 2005-February 5, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017" (2017). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 80. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 29. NUMBER 2. FALL 2017 Photo Credit: Tourism Vancouver See story on page 6 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of Communications) Designer: Meredith Affleck Vita Plume Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (TSA General Manager) President [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Natasha Thoreson and Sarah Molina Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Roxane Shaughnessy The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. -

Keynote Addressâ•Flsummary Notes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Keynote Address—Summary Notes Jack Lenor Larsen Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Larsen, Jack Lenor, "Keynote Address—Summary Notes" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 494. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/494 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Keynote Address—Summary Notes San Francisco Bay as the Fountainhead and Wellspring Jack Lenor Larsen Jack Lenor Larsen led off the 9th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America in Oakland, California, with a plenary session directed to TSA members and conference participants. He congratulated us, even while proposing a larger and more inclusive vision of our field, and exhorting us to a more comprehensive approach to fiber. His plenary remarks were spoken extemporaneously from notes and not recorded. We recognize that their inestimable value deserves to be shared more broadly; Jack has kindly provided us with his rough notes for this keynote address. The breadth of his vision, and his insightful comments regarding fiber and art, are worthy of thoughtful consideration by all who concern themselves with human creativity. On the Textile Society of America Larsen proffered congratulations on the Textile Society of America, now fifteen years old. -

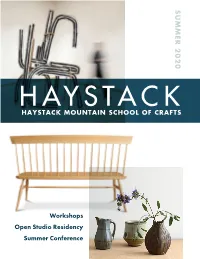

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Nohra Haime Gallery on Thursday, September 13Th from 6 to 8 P.M

N OHRA HAIME GALLERY FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 7 3 0 F I F T H A V E N U E OLGA DE AMARAL PLACES September 13 – November 24, 2012 “Gold is the Abstraction of Color.” -Olga de Amaral PUEBLO O, 2012, gesso, gold leaf, linen, acrylic, 39.37 x 78.74 in. 100 x 200 cm. OLGA DE AMARAL: PLACES an exhibition of 23 three-dimensional surfaces, will open at the Nohra Haime Gallery on Thursday, September 13th from 6 to 8 p.m. First exhibited in New York at the André Emmerich Gallery in 1973, Amaral’s abstract “golden surfaces of light” are unlike anything else. Transcending any one specific media, her work plays a unique balancing act between fine art and fiber art. Filling a gap that is virtually untouched, she pulls inspiration from Pre-Colombian weaving and Colonial gilding, abstracting them to the extent of universality. Gold has become a formal part of her vocabulary and renders her work collectively recognizable. Methodically assembled with a myriad of rectangular pre-fabricated pieces of fiber made into strips and rolls, the artist recreates the inner world of the universe. She choreographs these compositions with a labyrinth of winding, swirling and twisting interwoven patterns. Wind, light, mountains, trees, and rivers take heroic grandeur in her exploration of the universe. Departing from the static world of the two dimensional surface, she conceives monochromatic environments of shimmering presence and seduct ive forms. She weaves, cuts, molds, marks and tints her materials, fusing and merging them to create a tension that redefines the natural order of things. -

A New Method for the Conservation of Ancient Colored Paintings on Ramie

Liu et al. Herit Sci (2021) 9:13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00486-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A new method for the conservation of ancient colored paintings on ramie textiles Jiaojiao Liu*, Yuhu Li*, Daodao Hu, Huiping Xing, Xiaolian Chao, Jing Cao and Zhihui Jia Abstract Textiles are valuable cultural heritage items that are susceptible to several degradation processes due to their sensi- tive nature, such as the case of ancient ma colored-paintings. Therefore, it is important to take measures to protect the precious ma artifacts. Generally, ″ma″ includes ramie, hemp, fax, oil fax, kenaf, jute, and so on. In this paper, an examination and analysis of a painted ma textile were the frst step in proposing an appropriate conservation treat- ment. Standard fber and light microscopy were used to identify the fber type of the painted ma textile. Moreover, custom-made reinforcement materials and technology were introduced with the principles of compatibility, durabil- ity and reversibility. The properties of tensile strength, aging resistance and color alteration of the new material to be added were studied before and after dry heat aging, wet heat aging and UV light aging. After systematic examina- tion and evaluation of the painted ma textile and reinforcement materials, the optimal conservation treatment was established, and exhibition method was established. Our work presents a new method for the conservation of ancient Chinese painted ramie textiles that would promote the protection of these valuable artifacts. Keywords: Painted textiles, Ramie fber, Conservation methods, Reinforcement, Cultural relic Introduction Among them, painted ma textiles are characterized by Textiles in all forms are an essential part of human civi- the fexibility, draping quality, heterogeneity, and mul- lization [1]. -

California and the Fiber Art Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Oakland Museum of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Baizerman, Suzanne, "California and the Fiber Art Revolution" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 449. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/449 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Imogene Gieling Curator of Crafts and Decorative Arts Oakland Museum of California Oakland, CA 510-238-3005 [email protected] In the 1960s and ‘70s, California artists participated in and influenced an international revolution in fiber art. The California Design (CD) exhibitions, a series held at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1955 to 1971 (and at another venue in 1976) captured the form and spirit of the transition from handwoven, designer textiles to two dimensional fiber art and sculpture.1 Initially, the California Design exhibits brought together manufactured and one-of-a kind hand-crafted objects, akin to the Good Design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. -

Olga De AMARAL CV EDIT

Olga DE AMARAL b. 1932, Bogotá, Colombia Lives and works in Bogotá. EDUCATION 1954-55 Fabric Art, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI, USA. 1951-52 Architectural Design, Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca, Bogotá, Colombia. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Olga de Amaral, Victoria Beckham/Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, UK. The Light of Spirit, Galerie La Patinoire Royale/Valerie Bach, Miami, FL, USA. 2013 Olga de Amaral: Selected Works, Louise Blouin Foundation, London, UK. 2008 Golden Fleece, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv, Israel. 2007 Strata, Centro Cultural Casa de Vacas, Madrid, Spain. 2005 Resonancias, Centro Cultural de Belèm, Lisbon, Portugal. 2004 Threaded Words, Colombian Embassy in the United States, Washington D.C., USA. 2002 Tiempos y tierra, Museo de la Nación, Lima, Peru. Museo de Arte Moderno, Barranquilla, Colombia. 2001 Mes de Colombia, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1999 Hillside Terrace, Tokyo, Japan. Kreismuseum, Zons, Dormagen, Germany. Textilmuseum Max Berk, Heidelberg, Germany. Olga de Amaral: Woven Gold, The Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM, USA. 1998 Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI, USA. Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, USA. 1997 Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia, Cali, Colombia Art Museum of the Americas, Washington D.C., USA. Cleveland Institute of Art, Cleveland, OH, USA. Rétrospective, Musèe de la Tapisserie Contemporaine, Angers, France Olga de Amaral: Seven Stelae, Federal Reserve Board, Washington D.C., USA. University Art Museum Downtown, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. 1996 Museo de Arte de Pereira, Pereira, Colombia Nine Stelae and other Landscapes, Fresno Art Museum, Fresno, CA, USA. OUNM Center for the Arts, Albuquerque, NM, USA. -

Meanings of Kente Cloth Among Self-Described American And

MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER (Under the Direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst) ABSTRACT Little has been published regarding people of African descent’s knowledge, interpretation, and use of African clothing. There is a large disconnect between members of the African Diaspora and African culture itself. The purpose of this exploratory study was to explore the use and knowledge of Ghana’s kente cloth by African and Caribbean and American college students of African descent. Two focus groups were held with 20 students who either identified as African, Caribbean, or African American. The data showed that students use kente cloth during some special occasions, although they have little knowledge of the history of kente cloth. This research could be expanded to include college students from other colleges and universities, as well as, students’ thoughts on African garments. INDEX WORDS: Kente cloth, African descent, African American dress, ethnology, Culture and personality, Socialization, Identity, Unity, Commencement, Qualitative method, Focus group, West Africa, Ghana, Asante, Ewe, Rite of passage MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT By MARISA SEKOLA TYLER B.S., North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 ©2016 Marisa Sekola Tyler All Rights Reserved MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICANS AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER Major Professor: Patricia Hunt-Hurst Committee: Tony Lowe Jan Hathcote Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv DEDICATION For Isaiah and Lydia. -

Deliberate Entanglements: the Impact of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Deliberate Entanglements: The mpI act of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Zaiden, Emily, "Deliberate Entanglements: The mpI act of a Visionary Exhibition" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 887. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/887 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Deliberate Entanglements: The Impact of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden Figure 1. Deliberate Entanglements exhibition announcement designed by Timothy Andersen, UCLA Art Galleries, 1971. Courtesy Craft in America Center Archives. In the trajectory of fiber art history, the 1971 UCLA Art Galleries exhibition, Deliberate Entanglements, was exceptional in that it had an active and direct influence on the artistic movement. It has been cited in numerous sources, by participating artists, and by others who simply visited and attended as having had a lasting impact on their careers. In this day and age, it is rare for exhibitions at institutions to play such a powerful role and have a lasting impact. The exhibition was curated by UCLA art professor and fiber program head, Bernard Kester. From his post at UCLA, Kester fostered fiber as a medium for contemporary art.