West African Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

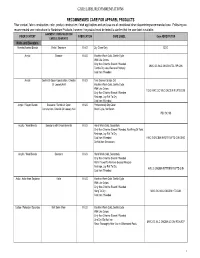

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Choosing the Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web

Choosing The Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web ABSTRACT You have decided that your web needs a synthetic fiber. There are three important factors that have to be considered: generic type, diameter, and length. In order to make the right choice, it is important to know the chemical and physical characteristics of the numerous man-made fibers, and to understand what is meant by terms such as denier and denier per filament (dpf). PROPERTIES Denier Denier is a property that varies depending on the fiber type. It is defined as the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of fiber. The current standard of denier is 0.05 grams per 450 meters. Yarn is usually made up of numerous filaments. The denier of the yarn divided by its number of filaments is the denier per filament (dpf). Thus, denier per filament is a method of expressing the diameter of a fiber. Obviously, the smaller the denier per filament, the more filaments there are in the yarn. If a fairly closed, tight web is desired, then lower dpf fibers (1.5 or 3.0) are preferred. On the other hand, if high porosity is desired in the web, a larger dpf fiber - perhaps 6.0 or 12.0 - should be chosen. Here are the formulas for converting denier into microns, mils, or decitex: Diameter in microns = 11.89 x (denier / density in grams per milliliter)½ Diameter in mils = diameter in microns x .03937 Decitex = denier x 1.1 The following chart may be helpful. Our stock fibers are listed along with their density and the diameter in denier, micron, mils, and decitex for each: Diameter Generic Type -

Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec

It Comes in Many Forms: Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec. 18, 2021 This exhibition presents textiles, decorative arts, and works on paper that show the breadth of Islamic artistic production and the diversity of Muslim cultures. Throughout the world for nearly 1,400 years, Islam’s creative expressions have taken many forms—as artworks, functional objects and tools, decoration, fashion, and critique. From a medieval Persian ewer to contemporary clothing, these objects explore migration, diasporas, and exchange. What makes an object Islamic? Does the artist need to be a practicing Muslim? Is being Muslim a religious expression or a cultural one? Do makers need to be from a predominantly Muslim country? Does the subject matter need to include traditionally Islamic motifs? These objects, a majority of which have never been exhibited before, suggest the difficulty of defining arts from a transnational religious viewpoint. These exhibition labels add honorifics whenever important figures in Islam are mentioned. SWT is an acronym for subhanahu wa-ta'ala (glorious and exalted is he), a respectful phrase used after every mention of Allah (God). SAW is an acronym for salallahu alayhi wa-sallam (may the blessings and the peace of Allah be upon him), used for the Prophet Muhammad, the founder and last messenger of Islam. AS is an acronym for alayhi as-sallam (peace be upon him), and is used for all other prophets before him. Tayana Fincher Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Fellow Costume and Textiles Department RISD Museum CHECKLIST OF THE EXHIBITION Spanish Tile, 1500s Earthenware with glaze 13.5 x 14 x 2.5 cm (5 5/16 x 5 1/2 x 1 inches) Gift of Eleanor Fayerweather 57.268 Heavily chipped on its surface, this tile was made in what is now Spain after the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238–1492). -

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Mud Cloth from Mali: Its Making and Use

ISSN 0378-5254 Tydskrif vir Gesinsekologie en Verbruikerswetenskappe, Vol 31, 2003 Mud cloth from Mali: its making and use Elsje S Toerien OPSOMMING INTRODUCTION Bogolanfini van Mali, beter bekend as mud cloth, The stark, geometric, black and white designs tradi- het in die laaste aantal jare bekendheid verwerf en tionally found on the mud cloths from Mali, can today daarby ook baie gewild geraak. be found on everything from clothing and furniture to book covers and wrapping paper. Along with kente Vir baie jare was dit nie duidelik hoe hierdie kleed- (from Ghana), mud cloth has become one of the best- stof gemaak is nie. Dit was algemeen aanvaar dat known African cloth traditions worldwide (Clarke, die ontwerpe deur 'n bleikingsproses verkry is. Van- 2001). Luke-Boone (2001:8) describes it as 'probably dag is dit bekend dat die ligte ontwerpe verkry word the most influential ethnic fabric of the 1990's'. The deur hulle met donker modder te omlyn en daarna designs have indeed become an important part of the die agtergrond in te vul. Afgesien van bogolanfini se modern ethnic look found in African-inspired fashions dekoratiewe waarde, het die verskillende motiewe today. ook simboliese waarde, en word verskillende kom- binasies gebruik om 'n geskiedkundige gebeurtenis te herdenk of 'n plaaslike held te vereer. In hierdie artikel word daar gekyk na die tegnieke wat gebruik word om bogolanfini te maak, na die betekenis van sommige motiewe, en die verskillen- de maniere waarop die tegnieke of motiewe gebruik word. Die redes vir die verhoogde belangstelling in, en vervaardiging van bogolanfini word ook aange- spreek. -

Smithsonian Institution

*» ^^^ *c^ N"-/^ ' ;.; »-5 . 3VVVV-O. c "Y^^i f . SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY: J. W. POWELL, DIRECTOR BULLET IN 27 TSTMSHIAN TEXTS FR^IsTZ BO^S WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 H U -2 CONTENTS Introduction _ o ' Texts: Txii'msEm and Lognl.iolfi' 7 Txii'msEui 25 Txii'msEni _ 36 The Stone and the Elderberry Bnsh 72 Tlie Porcupine and the Beaver 73 The Wolves and the Deer 83 The Stars 86 Rotten-feathers _ 94 K -'eLk" 1 02 The sealion hunters 108 Smoke-hole 116 Ts'ak- 117 Gro\ving-up-like-one-\vho-has-a-irnindniother_ i:!7 Little-eagle 169 She-\vho-has-a-lal)i'et-on-one-side 1S8 The Grizzly Bear 200 Squirrel 211 Witchcraft 217 Supiilementary stories: The origin of the G'ispawailuwE'da 221 Asi-hwi'l 225 The Grouses 229 TsEgu'ksk" 231 Rotten-feathers i continued from page 100) 234 Abstracts 236 3 TSIMSHIAN TEXTS Nass River Dialect Recorded and translated ])y Franz Boas INTRODUCTION The following texts were coUeeted in Kinkolith, at the mouth of the Nass river, during the months of November and December, 189-i, while I was engaged in researches under the auspices of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The principa] object of these investigations was a study of the Athapascan tribe of Port- land canal, and the following texts were collected incidentally only. The ethnologic results of these investigations were published in the reports of the Committee on the Northwestern Tribes of Canada of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.' The texts are in the Nass River dialect of the Tsimshian language. -

Dashikis Choose Your Perfect Fit

1 Dashikis Choose Your Perfect Fit S-XL Colors: 1X-6X Colors: Black Black/Blue Fuchsia Black/Dark Green Gold Black/Light Blue Green Black/Purple Light Blue Black/Red Maroon Black Red Blue Green Lime Military Green Mustard Red White/Lt Blue White/Lime White/Pink Yellow Mustard Blue Pink White/ Purple Traditional Print Dashiki - 3 Sizes King-Sized Dashikis Comes in sizes: Small (42”-44” chest), Choose from 1X, 2X, 3X, 4X, 5X, and 6X. Medium (46”-50” chest), and Large (48”-52” chest). 100% cotton. Made in India. C-U932 Made in Thailand. C-U918 Fitted Long Hoodie Elastic Sleeve Colors: Colors: Colors: Waist Burgundy Blue Black Green Light Blue Red Orange Lime Purple Maroon Yellow Orange Purple Red White / Black White / Blue Blue Gold Purple Traditional Elastic Dashiki Traditional Print Long-Sleeve Dashiki Trad Print Long Hoodie Up to a 42” bust, 32” long. Made in India Available in SM, MD, LG Available in LG, XL, 2X C-WS851 C-U940 C-U204 Colors: White Style 4 Navy Black Blue Brown Style 2 Black Batik Mud Print Mud Dashiki Lt. Blue Free size: Will fit up to a 52” bust and is 33” in length Embroidered Travelers Dashiki Kente Dashiki Fits up to a 50” chest. 35” length. 55% Fits up to 56” bust/chest measurement. with 19” sleeves. Plus size: Will fit up to a 56” bust and cotton/45% polyester. Made in India. C-U151 33” length. Made in India C-U920 is 36” in length with 20” sleeves. C-WH800 2 Best Sellers Black Red White/ Black/ White Black Light Blue White Blue Orange Traditional Print Luxury Skirt Set Polka Dot Maxi Skirt Mixed Print Denim Skirt - ASSORTED Make a bold statement with this traditional print It is 40” in length and fits up to a 48” elastic Fits up to 48” waist and is 41” long. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity by Tunde M. Akinwumi Department of Home Science University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract The paper investigated the nature of machine-produced fabric commercially termed African prints by focusing on a select sample of these prints. It established that the general design characteristics of this print are an amalgam of mainly Javanese, Indian, Chinese, Arab and European artistic tradition. In view of this, it proposed that the prints should reflect certain aspects of Africanness (Africanity) in their design characteristics. It also explores the desirability and choice of certain design characteristics discovered in a wide range of African textile traditions from Africa south of the Sahara and their application with possible design concepts which could be generated from Macquet’s (1992) analysis of Africanity. This thus provides a model and suggestion for new African prints which might be found acceptable for use in Africa and use as a veritable export product from Africa in the future. In the commercial parlance, African print is a general term employed by the European textile firms in Africa to identify fabrics which are machine-printed using wax resins and dyes in order to achieve batik effect on both sides of the cloth, and a term for those imitating or achieving a resemblance of the wax type effects. They bear names such as abada, Ankara, Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java Hollandis, Uniwax, ukpo and chitenge. Using the term ‘African Print’ for all the brand names mentioned above is only acceptable to its producers and marketers, but to a critical mind, the term is a misnomer and therefore suspicious because its origin and most of its design characteristics are not African.