The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloth Without Weaving: Beaten Barkcloth of the Pacific Islands, November 1, 2000-February 18, 2001

Cloth Without Weaving: Beaten Barkcloth of the Pacific Islands, November 1, 2000-February 18, 2001 Unlike most textiles, which are made of interworked yarns, beaten barkcloth is made of strips of the inner bark of trees such as the paper mulberry, breadfruit, or fig, pounded together into a smooth and supple fabric. It is an ancient craft, practiced in southern China and mainland Southeast Asia over 5,000 years ago. From there, the skill spread to eastern Indonesia and the Pacific Islands. While the technique is also known in South America and Africa, it is most closely associated with the islands of Polynesia. In Polynesia, the making of beaten barkcloth, or tapa, as it is commonly known, is primarily women's work. The technique is essentially the same throughout the Pacific Islands, with many local variations. Bark is stripped from the tree, and the inner bark separated from the outer. The inner bark is then pounded with wooden beaters to spread the fibers into a thin sheet. Large pieces of tapa can be made by overlapping and pounding together several smaller sheets. Women decorate the cloth in many ways, and techniques are often combined. Mallets carved or inlaid with metal or shell designs may impart a subtle texture to the surface. Color may be applied with stamps, stencils, freehand painting, or by rubbing dye into the tapa over a patterned board. Glazes may be brushed onto the finished cloth. Each tapa-producing culture has its own vocabulary of recognized decorative motifs. Many pattern names are drawn from the natural world, and the motifs appear as highly stylized images of local flora and fauna or simple geometric shapes. -

Textile Printing

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1004 TEXTILE PRINTING This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. INTRODUCTION The desire of adding color and design to textile materials is almost as old as mankind. Early civilizations used color and design to distinguish themselves and to set themselves apart from others. Textile printing is the most important and versatile of the techniques used to add design, color, and specialty to textile fabrics. It can be thought of as the coloring technique that combines art, engineering, and dyeing technology to produce textile product images that had previously only existed in the imagination of the textile designer. Textile printing can realistically be considered localized dyeing. In ancient times, man sought these designs and images mainly for clothing or apparel, but in today’s marketplace, textile printing is important for upholstery, domestics (sheets, towels, draperies), floor coverings, and numerous other uses. The exact origin of textile printing is difficult to determine. However, a number of early civilizations developed various techniques for imparting color and design to textile garments. Batik is a modern art form for developing unique dyed patterns on textile fabrics very similar to textile printing. Batik is characterized by unique patterns and color combinations as well as the appearance of fracture lines due to the cracking of the wax during the dyeing process. Batik is derived from the Japanese term, “Ambatik,” which means “dabbing,” “writing,” or “drawing.” In Egypt, records from 23-79 AD describe a hot wax technique similar to batik. -

Mud Cloth from Mali: Its Making and Use

ISSN 0378-5254 Tydskrif vir Gesinsekologie en Verbruikerswetenskappe, Vol 31, 2003 Mud cloth from Mali: its making and use Elsje S Toerien OPSOMMING INTRODUCTION Bogolanfini van Mali, beter bekend as mud cloth, The stark, geometric, black and white designs tradi- het in die laaste aantal jare bekendheid verwerf en tionally found on the mud cloths from Mali, can today daarby ook baie gewild geraak. be found on everything from clothing and furniture to book covers and wrapping paper. Along with kente Vir baie jare was dit nie duidelik hoe hierdie kleed- (from Ghana), mud cloth has become one of the best- stof gemaak is nie. Dit was algemeen aanvaar dat known African cloth traditions worldwide (Clarke, die ontwerpe deur 'n bleikingsproses verkry is. Van- 2001). Luke-Boone (2001:8) describes it as 'probably dag is dit bekend dat die ligte ontwerpe verkry word the most influential ethnic fabric of the 1990's'. The deur hulle met donker modder te omlyn en daarna designs have indeed become an important part of the die agtergrond in te vul. Afgesien van bogolanfini se modern ethnic look found in African-inspired fashions dekoratiewe waarde, het die verskillende motiewe today. ook simboliese waarde, en word verskillende kom- binasies gebruik om 'n geskiedkundige gebeurtenis te herdenk of 'n plaaslike held te vereer. In hierdie artikel word daar gekyk na die tegnieke wat gebruik word om bogolanfini te maak, na die betekenis van sommige motiewe, en die verskillen- de maniere waarop die tegnieke of motiewe gebruik word. Die redes vir die verhoogde belangstelling in, en vervaardiging van bogolanfini word ook aange- spreek. -

H'mong Ancient Methods of Indigo Dyeing and Beeswax Batik in Cat

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 H’mong Ancient Methods of Indigo Dyeing and Beeswax Batik in Cat CAT Village, Hoang Lien Commune, SAPA Town, Lao Cai Province, Vietnam Le Thi Hanh Lien1*, Nguyen Thi Hai Yen2, Dao Thi Luu3, Phi Thi Thu Hoang4, Nguyen Thuy Linh5 1, 2, 3, 4 Institute of Geography, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Nghia Do, CauGiay District, Ha Noi, Vietnam 5Management Development Institute of Singapore *Corresponding author: lehanhlien2017[at]gmail.com Abstract: Indigo dyeing and beeswax batik are the two traditional crafts that have long been associated with the H’Mong people in Sa Pa in general, Cat Cat village in particular and still preserved until the presentday. Through many stages of making indigo dye combined with sophisticated techniques and the ingenuity, meticulousness of the artisans in each motif and pattern, unique beeswax batik and indigo dyeing products have been created bringing the cultural identity of the H’mong people. These handicraft products have become a highlight to attract tourists to learn and discover local cultural values and they are meaningful souvenirs for visitors after each trip. In recent years, the development of the community-based tourism model in Cat Cat village has brought many benefits to the local community. Meanwhile, it has also contributed to creating opportunities for the development and restoration of H’mong traditional crafts. Keywords: indigo dyeing, beeswax batik, H’Mong, Cat Cat, Sa Pa 1. Introduction cultural and religious life of the H'Mong. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits. -

Double Corduroy Rag

E-newes - coming to you monthly! Get connected: Visit schachtspindle.com for helpful Each issue includes a project, hints, project ideas, product manuals and informa- tion. Follow our blog, like us on Facebook, pin us on helpful tips & Schacht news. Pinterest, visit Schacht groups on Ravelry, follow us TM on Twitter. News from the Ewes DECEMBER 2014 Blanket Weaving in the Southwest. We What is a countermarche loom liked Loie Stenzel’s suggestion for us- and why do we love it for rugs? Project ing patterned as well as solid fabrics, Double Corduroy Rag Rug Before I tell you why we love our countermarche so I spent some time by Chase Ford Cranbrook loom for rug weaving, I want to give you familiarizing myself After weaving off the mohair blanket a very brief overview of three systems for creating with the color pal- sheds. on the Cranbrook Loom (see pictures ettes that appeared On jack looms, on our Facebook), Jane and I decided in the blankets in when the treadle is that a double corduroy rug would be Wheat’s book. I depressed, some shafts fun to try. Corduroy is a pile weave that found several colors raise and the others is created by weaving floats along with and prints of a light- remain stationary. Jack a ground weave. The floats are cut after weight 100% cotton looms are the most weaving to form the pile. Corduroy can fabric to sample Rug sample popular style of looms be either single or double. Generally, with. in the U.S. and is the system we use for our Wolf and Standard Floor Looms. -

How Is Chintz Made and Where Does It Originate? Where Is It Commonly

How is chintz 1. It is a closely woven, lustrous, plain weave cotton fabric, printed or made and where plain, that has been glazed with starch or glue and then friction does it originate? calendered. Much used for curtains and upholstery. Where is it 2. It was originally a painted or stained calico produced in India and commonly used? popular for bed covers, quilts and draperies, popular in Europe in 17th century and 18th century, where it was imported and later produced. Europeans at first produced reproductions of Indian designs, and later added original patterns. 3. A well-known make was toile de Jouy, which was manufactured in Jouy, France between 1700 and 1843. Today it usually consists of bright patterns printed on a light background. Which weave is used 1. It is a rich fabric using the Jacquard weave where an all over to produce Brocade, interwoven design usually floral patterns. and where is it used? 2. It is used for upholstery and other interior products and often incorporates gold, silver or other metallic yarns. 3. It is also used in Chinese garments. 4. Brocade is typically woven on a draw loom. It is a supplementary weft technique, that is, the ornamental brocading is produced by a supplementary, non-structural, weft in addition to the standard weft that holds the warp threads together. The purpose of this is to give the appearance that the weave actually was embroidered on. How are chenille yarns 1. The weft yarn is manufactured by placing short lengths of yarn, called made and how are they the "pile", between two "core yarns" and then twisting the yarn used? together. -

Glossary of Carpet and Rug Terms

Glossary of Carpet and Rug Terms 100% Transfer - The full coverage of the carpet floor adhesive into the carpet backing, including the recesses of the carpet back, while maintaining full coverage of the floor. Absorbent Pad (or Bonnet) Cleaning - A cleaning process using a minimal amount of water, where detergent solutions are sprayed onto either vacuumed carpet, or a cotton pad, and a rotary cleaning machine is used to buff the carpet, and the soil is transferred from the carpet to the buff pad, which is changed or cleaned as it becomes soiled. Acrylic/Modacrylic - A synthetic fiber introduced in the late 1940's, and carpet in the late 1950's, it disappeared from the market in the late 1980's due to the superior performance of other synthetics. Acrylics were reintroduced in 1990 in Berber styling to take advantage of their wool-like appearance. Modacrylic is a modified acrylic. While used alone in bath or scatter rugs, in carpeting it's usually blended with an acrylic. Acrylics are known for their dyeability, wearability, resistance to staining, color retention and resistance to abrasion. They're non-allergenic, mildew proof and moth proof. Adhesive - A substance that dries to a film capable of holding materials together by surface attachment. Anchor Coat - A latex or adhesive coating applied to the back of tufted carpet, to lock the tufts and prevent them from being pulled out under normal circumstances. Antimicrobial - A chemical treatment added to carpet to reduce the growth of common bacteria, fungi, yeast, mold and mildew. Antistatic - A carpet's ability to dissipate an electrostatic charge before it reaches a level that a person can feel. -

Schiffer Fashion Press BACKLIST 1 3 Plaids: a Visual Survey of Pattern

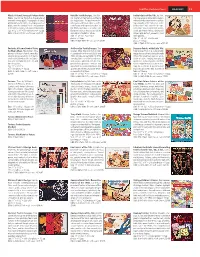

Schiffer Fashion Press BACKLIST 13 Plaids: A Visual Survey of Pattern Varia- Metallic Textile Designs. Tina Skin- Funky Fabrics of the ’60s. Joy Shih. tions. Tina Skinner. More than fi ve decades of ner. They’re hot, they’re shiny, and they’re The wide range of sixties fabric designs twentieth century plaids. Photographs of actual oh-so-glamorous. This book revisits me- refl ected the transition from the comfort- printed and woven textiles. A sweeping survey of tallic’s past, with historic fabric swatches ing tranquility of the early years to the plaids, from the standard checks and ginghams from Europe and Japan dating back to bolder, more “hip” end of the decade. to the farthest reaches of designers’ imaginations. the 1950s, and takes us to today’s top A nostalgic tour of pastel and splashy Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 558 color photos • 112 pp. European couture houses in a visual fl orals, patchwork calicos, denims and ISBN: 0-7643-0481-X • soft cover • $24.95 exploration of metallics’ allure. stripes, wild abstract geometrics, and Size: 11" x 8 1/2" • 237 color neon paisleys. photos • 112 pp. Size: 11" x 8 1/2" • 250+ color ISBN: 0-7643-0635-9 • soft cover • $19.95 photos • 112 pp. ISBN: 0-7643-0174-8 • soft cover • $19.95 Foulards: A Picture Book of Prints Art Deco Era Textile Designs. Tina Designer Fabrics of the Early ‘60s. for Men’s Wear. Tina Skinner. 350+ Skinner. More than 300 historic fab- Tina Skinner. From top couture fabric photos of historic fabric swatches ric samples from the mid-1920s and design houses of Paris during the early explore design variations in foulards, 1930s provide a visual textbook of the 1960s, this visual feast explores a mul- small motifs printed on silks and fabrics everyday fabrics used for housedresses titude of styles, ranging from playful that were intended for men’s ties and and curtains, adorned with the era’s geometrics to novelty prints and from dressing gowns. -

Antiques, Furnishings, Collectors' Items, Textiles & Vintage Fashion

Antiques, Furnishings, Collectors' Items, Textiles & Vintage Fashion Thursday 23rd November 2017, 10am Viewing Wednesday 22nd November 10.30am-6pm and day of sale from 9am THE OLD BREWERY BAYNTON ROAD ASHTON BS3 2EB [email protected] 0117 953 1603 www.bristolauctionrooms.co.uk Live Bidding at @BristolAuctionRooms @BristolSaleroom BUYERS PREMIUM 24% (INCLUSIVE OF VAT) PLUS VAT ON THE HAMMER PRICE AT 20% WHERE INDICATED Sale No. 191 Catalogue £2 IMPORTANT NOTICES We suggest you read the following guide to buying at Bristol Auction Rooms in conjunction with our full Terms & Conditions at the back of the catalogue. HOW TO BID To register as a buyer with us, you must register online or in person and provide photo and address identification by way of a driving licence photo card or a passport/identity card and a utility bill/bank statement. This is a security measure which applies to new registrants only. We operate a paddle bidding system. Lots are offered for sale in numerical order and we usually offer approximately 80-120 lots per hour. We recommend that you arrive in plenty of time before the lots you are wishing to bid on are up for sale. ABSENTEE BIDS If you cannot attend an auction in person, Bristol Auction Rooms can bid on your behalf, acting upon your instructions to secure an item for you at the lowest possible price as allowed by other bids and reserves. You can leave bids in person, through our website, by email or telephone - detailing your intended bids clearly, giving your price limit for each lot (excluding Buyer’s Premium and VAT). -

Mounting Barkcloth with Rare Earth Magnets

Mounting barkcloth with rare earth magnets: the compression and fiber resiliency answer Gwen Spicer Abstract The use of magnets to mount barkcloth is common, yet details of the specific techniques used had not been adequately documented. An investigation of magnetic systems globally found that while all current systems use 'point fasteners' on the surface of the cloth, this is where the similarities end. The unresolved question for mounting barkcloth is the potential for compression. Compression is a significant issue for art works on paper, especially when magnets are located on the face. How are backcloth and paper different? While researching various materials frequently placed together and used within a magnetic mounting system, otherwise known as ‘the gap’, some interesting ancillary results were found. Materials are typically selected for their archival value, which includes their long-term stability. Over time, a set of preferred materials became well established; these encompass both natural and synthetic materials, woven and non-woven alike. The phrase ‘like with like’ is often used when materials are selected. This long-held philosophy should be re-examined. Compression relates to an object’s ability to regain shape once a force is applied, one aspect of its resiliency. It appears that barkcloth is less likely to experience compression than does paper, although both media are cellulosic. Cellulose is rated as a low-resilience fiber, when compared to proteins and polyester. These materials most likely have different compression potentials due to the different ways in which paper and barkcloth are prepared. This and other surface phenomena will be discussed. The investigation will briefly summarise why the 'point-fasteners' system appear to be favoured over ‘large area pressure.’ Introduction The conservation and mounting of barkcloth has long been a challenge.