Designing Under the Impact of the Land Issue – from Sitte to Bernoulli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruno Tauts Hufeisensiedlung Und Das UNESCO-Welterbe „Siedlungen Der Berliner Moderne“

PRESSEEINLADUNG ZUR BUCHPRÄSENTATION Bruno Tauts Hufeisensiedlung und das UNESCO-Welterbe „Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne“ Termin: Mittwoch, den 5. Oktober 2016, 19.00 – 20.30 Uhr Ort: Buchhandlung Bücherbogen am Savignyplatz, Berlin-Charlottenburg Veranstalter: Ben Buschfeld/buschfeld.com, Deutscher Werkbund Berlin, Bücherbogen ZUM THEMA: Mit seinen Wohnsiedlungen setzte der Visionär, Architekt und Stadtplaner Bruno Taut (1880–1938) zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts Maßstäbe. Vor allem das 1925–1930 errichtete Denkmalensemble Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin-Britz wird international als Schlüsselwerk des reformorientierten Wohnungsbaus gewürdigt. Die sehr farbenfroh, variantenreich und mit vielen Gärten und Freiflächen gestaltete denkmalgeschützte Siedlung gruppiert sich um eine 350 Meter lange, in Form eines DE • EN Hufeisens erbaute Gebäudeformation. Das knapp 2.000 gut geschnittene Wohneinheiten BRUNO TAUTs umfassende Ensemble folgte damals dem populären Leitbild „Licht, Luft und Sonne BEN BUSCHFELD für alle“ und zeigt, wie ab 1920 im Zuge des Zusammenschlusses der Region zu „Groß- Berlin“ neue durchgrünte Stadtquartiere entstehen konnten. Hierbei avancierte der auf Bruno Taut zurückgehende Teil der Großsiedlung Britz bereits früh zu einer Ikone des „Neuen Bauens“. Bis heute gilt die Anlage als die bekannteste der sechs, 2008 zum UNESCO-Welterbe erklärten, „Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne“. Die seinerzeit von einer städtischen Gesellschaft errichtete, seit 1998 privatisierte Siedlung ist aber auch aus einem aktuellen Blickwinkel ein interessantes -

Abstract: Datenbank Hufeisensiedlung

30. Berliner Denkmaltag am 15. April 2016 Denkmal digital. Dokumentieren – Kommunizieren – Mobilisieren“ Technische Universität Berlin, Architekturgebäude, Raum A053 Ben Buschfeld, Dipl. Designer Abstract: Datenbank Hufeisensiedlung Die von dem Architekten Bruno Taut, Stadtbaurat Martin Wagner und dem Gartenarchitekten Leberecht Migge gestaltete, zwischen 1925 und 1930 von der GEHAG errichtete Hufeisensiedlung in Neukölln-Britz gilt international als Schlüsselwerk modernen städtischen Siedlungsbaus. Sie umfasst knapp 2.000 Wohneinheiten und steht seit 1986 als Gesamtensemble unter Denkmalschutz. Im Juli 2008 wurde sie, gemeinsam mit fünf weiteren Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne, in die UNESCO-Welterbeliste aufgenommen, seit 2010 ist sie zusätzlich eingetragenes Gartendenkmal. Der 1998 erfolgte Verkauf der städtischen Wohnungsbaugesellschaft GEHAG mündete in verschiedenen Übernahmen deren umfangreichen Gebäude-Portfolios am Finanzmarkt. Er befindet sich heute im Eigentum der Deutsche Wohnen AG, die damit ein Großteil der Berliner Welterbesiedlungen besitzt und – speziell in der Hufeisensiedlung – seit 2000/2001 begann, die Reihenhausbestände sukzessive als Einzeleigentum zu verkaufen. Diese Situation bringt eine Zersplitterung der Eigentumsverhältnisse in dem von Taut sehr virtuos und detailreich variierten Denkmalensemble mit sich und erschwert dessen denkmalgerechten Erhalt. Die 679, je mit einem Garten versehenen, Reihenhäuser befinden sich heute fast komplett in Einzeleigentum. Dies bedeutet, dass mehrere Hundert private, nicht fachlich -

Leberecht Migge

Leberecht Migge 1881-1935 Gartenkultur des 20.Jahrhunderts Herausgegeben vom Fachbereich Stadt und Landschaftsplanung der Gesamthochschule Kassel Worpsweder Verlag 4 Dieses Buch erscheint 7 Vorwort zur Ausstellung "Leberecht Migge 9 Biographie Gartenkultur des 20. Jahr hunderts" anläßlich der 10 leberecht Migge - Spartakus in Grün Jürgen v. Reuß Bundesgartenschau Kassel - Das konsequente Experiment des Sonnenhofs in 1981. Ausstellung und Worpswede Katalog wurden ermöglicht durch finanzielle Hilfe der - Im übrigen war er ein streitbarer Herr ... Bundesgartenschau - Die Konsequenz des Worpsweder Experiments GmbH. - Die intensive Siedlerschule Worpswede Autoren - Der Sonnenhof Prof. Dr. Lucius Burckhardt, GhK 33 "Die produktive Siedlungsloge" Leberecht Migge Dipl.lng. Heidrun Hubenthai, GhK 37 Migge und der Werkbund Lucius Burckhardt Prof. Diplomgörtner 40 Gartenkultur statt Gartenkunst Jürgen v. Reuß Jürgen v. Reuß,GhK Prof. Dipl. Ing. - Leberecht Migges Werdegang vom künstlerischen Leiter Klaus Stadler, einer Gartenbaufirma zum Propagandisten in der FH Weihenstephan Siedlungsfrage Dr. Ing. Günther Uhlig, - Migges Position in der Debatte um den Gartenstil RWTH Aachen Prof. Dipl. Ing. - Die architektonische Form als Voraussetzung für den Michael Wilkens, GhK Gebrauch des Gartens - Typus und Laienhilfe als Mittel zur Verbreiterung der Inhaltliche Konzeption und Gartenkultur Durchführung der Ausstellung - Der "Kommende Garten" Ulrike Haas-Kirchner Heidrun Hubenthai 66 Texte zum "Kommenden Garten" Leberecht Migge Jürgen von Reuß 72 Die Idee -

Leseprobe 9783791385280.Pdf

Our Bauhaus Our Bauhaus Memories of Bauhaus People Edited by Magdalena Droste and Boris Friedewald PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 7 Preface 11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter Dexel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920–1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sándor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes -

100 Years of Bauhaus

Excursions to the Visit the Sites of the Bauhaus Sites of and the Bauhaus Modernism A travel planner and Modernism! ↘ bauhaus100.de/en # bauhaus100 The UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the Sites of Bauhaus Modernism Hamburg P. 31 Celle Bernau P. 17 P. 29 Potsdam Berlin P. 13 Caputh P. 17 P. 17 Alfeld Luckenwalde Goslar Wittenberg P. 29 P. 17 Dessau P. 29 P. 10 Quedlinburg P. 10 Essen P. 10 P. 27 Krefeld Leipzig P. 27 P. 19 Düsseldorf Löbau Zwenkau Weimar P. 19 P. 27 Dornburg Dresden P. 19 Gera P. 19 P. 7 P. 7 P. 7 Künzell P. 23 Frankfurt P. 23 Kindenheim P. 25 Ludwigshafen P. 25 Völklingen P. 25 Karlsruhe Stuttgart P. 21 P. 21 Ulm P. 21 Bauhaus institutions that maintain collections Modernist UNESCO World Heritage Sites Additional modernist sites 3 100 years of bauhaus The Bauhaus: an idea that has really caught on. Not just in Germany, but also worldwide. Functional design and modern construction have shaped an era. The dream of a Gesamtkunst- werk—a total work of art that synthesises fine and applied art, architecture and design, dance and theatre—continues to this day to provide impulses for our cultural creation and our living environments. The year 2019 marks the 100 th anniversary of the celebration, but the allure of an idea that transcends founding of the Bauhaus. Established in Weimar both time and borders. The centenary year is being in 1919, relocated to Dessau in 1925 and closed in marked by an extensive programme with a multitude Berlin under pressure from the National Socialists in of exhibitions and events about architecture 1933, the Bauhaus existed for only 14 years. -

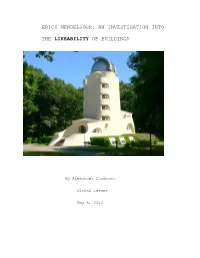

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level). -

La Siedlung Como Idea De Ciudad Großsiedlung Britz Hufeisensiedlung · Großsiedlung Siemensstadt

La Siedlung como idea de ciudad Großsiedlung Britz Hufeisensiedlung · Großsiedlung Siemensstadt Ana Duque Asens · TFG · Aula 1 · Curso 2015/2016 ETSAM · Universidad Poltécnica de Madrid Tutor: José Manuel García Roig La Siedlung como idea de ciudad 4 TFG · Ana Duque Asens Índice Presentación. 1. Objetivos del Trabajo y metodología. 2. Contexto histórico y social de las Siedlungen. 2.1. La República de Weimar (1918-1933). 2.2. La política social. 2.3. Arte y cultura. 3. Arquitectura y urbanismo en los años 20. El nuevo concepto de ciudad. 3.1. La Nueva Construcción y el Racionalismo. Die neue Sachlichkeit. 3.2. Die Städtebau, los cambios en la constitución de la forma urbana. 4. Estudio de las Siedlungen. 4.1. Los problemas de la vivienda y la arquitectura social alemana. 4.1.1. Principales problemas de la vivienda en Berlín. 4.1.2. Estrategias políticas y sociales para la construcción de las grandes Siedlungen berlinesas. 4.1.3. Martin Wagner y su papel como Stadtbaurat de Berlin. 4.2. Estructura y tipología urbana de Berlín. Plano del Gran Berlín del año 1920. 4.3. Características principales que diferencian las Siedlungen de otros sistemas residenciales. 5. Análisis detallado de casos: objetivos, desarrollo y limitaciones. 5.1. Großsiedlung Britz Hufeisensiedlung. 5.2. Großsiedlung Siemensstadt. 6. Comparativa del estudio de casos. 7. Conclusiones. 5 La Siedlung como idea de ciudad 6 TFG · Ana Duque Asens Presentación Este trabajo de fin de grado es una investigación personal sobre las colonias sociales que se construyeron en centro Europa, sobretodo en Alemania, en el periodo de entre Guerras (1914-1933). -

Home Stories 100 Jahre, 20 Visionäre Interieurs 8

Home Stories 100 Jahre, 20 visionäre Interieurs 8. Februar 2020 bis 28. Februar 2021 Vitra Design Museum Charles-Eames-Str. 2 79576 Weil am Rhein Deutschland #VDMHomeStories Unser Zuhause ist Ausdruck unseres Lebensstils, es prägt unseren Alltag und bestimmt unser Wohlbefinden. Mit der Ausstellung »Home Stories. 100 Jahre, 20 visionäre Interieurs« initiiert das Vitra Design Museum eine neue Debatte über das private Interieur, seine Geschichte und seine Zukunftsperspektiven. Die Ausstellung führt den Besucher auf eine Reise in die Vergangenheit und zeigt, wie sich gesellschaftliche, politische und technische Veränderungen der letzten 100 Jahren in unserem Wohnumfeld widerspiegeln. Im Zentrum stehen die großen Zäsuren, die das Design und die Nutzung des westlichen Interieurs geprägt haben – von aktuellen Themen wie knapper werdendem Wohnraum und dem Verschwinden der Grenzen zwischen Arbeits- und Privatleben über die Entdeckung der Loftwohnung in den 1970er Jahren, aber auch dem Siegeszug einer ungezwungeneren Wohnkultur in den 1960ern und dem Einzug moderner Haushaltsgeräte in den 1950ern bis hin zu den ersten offenen Grundrissen der 1920er Jahre. Diese Umbrüche werden anhand von 20 stilbildenden Interieurs veranschaulicht, darunter Entwürfe von Architekten wie Adolf Loos, Finn Juhl, Lina Bo Bardi oder Assemble, Künstlern wie Andy Warhol oder Cecil Beaton sowie der legendären Innenarchitektin Elsie de Wolfe. Die Gestaltung und Produktion von Möbeln, Textilien, Dekorationselementen und Lifestyle- Accessoires für das Zuhause beschäftigt heute eine gigantische, globale Industrie. Die neuesten Interieur-Trends unterhalten eine ganze Medienlandschaft aus Zeitschriften, Fernsehsendungen, Blogs und Social-Media-Kanälen. Doch während soziale und architektonische Themen wie die Frage nach bezahlbarem Wohnraum heute lebhaft debattiert werden, findet eine ernsthafte gesellschaftliche Auseinandersetzung über das Wohninterieur nicht statt. -

Maybrief 041 September/2015

maybrief 041 September/2015 Das Vermächtnis der Moderne Die Stadt und das Erbe des Neuen Frankfurt / Lichtblick in Praunheim / Ein Haus am Nonnen- pfad / Moderne als Geschichte / Zeitloses Erbe am Ural / Sonderausstellung: Utopien des Neuen Frankfurt www.ernst-may-gesellschaft.de inhalt in dieser ausgabe 03 editorial 18 ausstellung Dr. Eckhard Herrel Utopien des Neuen Frankfurt Christina Treutlein 04 thema Die Stadt und das Erbe des Neuen Frankfurt 20 ernst-may-gesellschaft Dr. Christoph Mohr mayfest 129 Dr. Peter Paul Schepp 06 thema Lichtblick in Praunheim 21 ernst-may-gesellschaft Cornelius Boy Ein Tag für die Literatur mit Klaus Meier-Ude Theresia Marie Jekel 08 thema Ein Haus am Nonnenpfad 22 ernst-may-gesellschaft Roswitha Väth Ernst May im Film: "Eine Revolution des Großstädters" C. Julius Reinsberg 10 thema Moderne als Geschichte 24 ernst-may-gesellschaft Prof. Dr.-Ing. Andreas Schwarting Arbeitersiedlungen im Frankfurter Westen Dr. Klaus Strzyz 12 thema Zeitloses Erbe am Ural 25 ernst-may-gesellschaft Margarita Migunova, Magnitogorsk 13. orderntliche Mitgliederversammlung Dr. Peter Paul Schepp 14 thema "Alte Scheunen..." 26 szene Dr. Karin Berkemann Wo die Kosmonauten wohnen C. Julius Reinsberg 16 thema Die Gustav-Adolf-Kirche in Niederursel 27 szene Dr. Konrad Elsässer Wolkenkratzer-Utopien C. Julius Reinsberg 17 thema Ein Seminar zur Architektur der Moderne in Frankfurt 28 szene Karl-Eberhard Feußner Berlin grüßt Frankfurt - mit Tauts Hufeisensiedlung Wilhelm E. Opatz 29 nachrichten 31 forum Foto oben: Dessau, Meisterhäuser, Straßenseite. Von links: Direktorenhaus, Haus Moholy-Nagy (Bruno Fioretti Marquez), Haus Feininger (Walter Gropius) (Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Foto Martin Brück 2015). Foto rechts: Bastion in der Römerstadt (Foto: Horst Ziegenfusz) Titelbild: Klassisch-modernes Schwimmbad an einem verschwiegenen Ort in Thüringen (Foto: Holger Bär, www.visual-dreams.de) 2 / maybrief 41 ernst-may-gesellschaft e.V. -

Volk Elterthe Limits of Community—The

Downloaded from The Limits of Community—The http://oaj.oxfordjournals.org Possibilities of Society:vol On Modernk Architecture in Weimar Germany at University of California Santa Barbara on April 28, 2010 elter Volker M. Welter Downloaded from http://oaj.oxfordjournals.org at University of California at Santa Barbara on April 28, 2010 The Limits of Community – The Possibilities of Society: On Modern Architecture in Weimar Germany Volker M. Welter Downloaded from 1. Ferdinand To¨nnies, Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Abhandlung des Communismus und Socialismus als empirischer Kulturformen (Fues: Leipzig, 1887). In the historiography of early-twentieth-century modern German architecture 2. Ferdinand To¨nnies, Gemeinschaft und and urban planning, the idea of community has been a major analytical Gesellschaft. Grundbegriffe der reinen Soziologie (Karl category. Whether garden city, garden suburb, workers’ housing, factory http://oaj.oxfordjournals.org Curtius: Berlin, 1912). The third edition was estate, or social housing estate, the often unified architectural forms seem to published in 1920, the combined fourth and fifth edition in 1922, the combined sixth and seventh suggest community. Any enclosing geometric urban form is often understood in 1926, and an eighth edition in 1935. to strengthen the introverted character that clearly separates such settlements from the big city. In short, these communities are depicted as shining beacons 3. Helmuth Plessner, Die Grenzen der Gemeinschaft. Eine Kritik des sozialen Radikalismus of a new social order in the otherwise harsh urban surroundings of society. (Friedrich Cohen: Bonn, 1924). In the following I Stylistically, such communities were designed in both traditionalist and use Helmuth Plessner, The Limits of Community. -

The ECB Main Building

Main Building November 2020 Contents 1 Overview 2 1.1 The commencement Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.2 Project Milestones 8 1.3 Building Description 14 1.4 Site 19 1.5 Energy Design 27 1.6 Sustainability 29 1.7 Memorial 31 1.8 Photo Gallery Timeline (2004-2015) 34 2 Competition 35 2.1 Competition phases 37 2.2 Competition format 54 3 Planning Phase 56 3.1 Different planning phases 56 3.2 Optimisation phase 57 3.3 Preliminary planning phase 59 3.4 Detailed planning phase 60 3.5 Execution planning phase 62 4 Construction Phase 65 4.1 Preliminary works 65 4.2 Structural work 71 4.3 Façade 82 4.4 Landscape architecture 85 5 Appendix 87 Main Building – Contents 1 1 Overview 1.1 The project begins 1.1.1 A new home for the ECB Upon a recommendation by the European Court of Auditors to all European institutions that it is much more economical in the long term to own premises rather than to rent office space, the ECB built its own premises on the site of the Grossmarkthalle (Frankfurt’s former wholesale market hall). The premises were designed by Vienna-based architects COOP HIMMELB(L)AU. Figure 1 185 m high office tower Main Building – Overview 2 Figure 2 120,000 m² entire site area Figure 3 250 m long Grossmarkthalle 1.1.2 Choosing the location When the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1992, it was decided that the ECB would be located in Frankfurt am Main. In 1998, when the ECB started operations in rented offices in the Eurotower, the search for a suitable site for its own premises in Frankfurt began. -

Letters to His Parents

ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page i Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary's Letters to his Parents ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page ii Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page iii Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary theodor w. adorno Letters to his Parents 1939–1951 Edited by Christoph Gödde and Henri Lonitz Translated by Wieland Hoban polity ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page iv Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary First published in German as Theodor W. Adorno: Briefe an die Eltern 1939–1951 and copyright © Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2003. This English translation © Polity Press 2006 Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN-10: 0-7456-3542-3 ISBN-13: 978-07456-3542-3 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12pt Sabon by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed and bound in Malaysia by Alden Press, Malaysia For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page v Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary's Contents Editors’ Foreword vi Letters 1939 1 1940 33 1941 67 1942 78 1943 122 1944 164 1945 210 1946 242 1947 273 1948 312 1949 347 1950 379 1951 383 Index 386 v ADORNO LETTERS PRELIMS.qxd 16/8/06 1:50 PM Page vi Gary Gary's G4:Users:Gary:Public:Gary Editors’ Foreword When Adorno saw his parents again in June 1939 in Havana, they had only been in Cuba for a few weeks.