13 Shantanu Nevrekar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab)

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2018 34 ISSN 2250-3153 Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab) Kamaljit Kaur DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 Abstract: This study deals with the spatial analysis of growth of urban population. Malwa region has been taken as a case study. During 1991-2001, the urban growth has been shown in Malwa region of Punjab. The large number of new towns has emerged in this region during 1991-2001 periods. Urban growth of Malwa region as well as distribution of urban centres is closely related to accessibility and modality factors. The large urban centres are located along major arteries. International border with an unfriendly neighbour hinders urban growth. It indicates that secondary activities have positive correlation with urban growth. More than 90% of urban population of Malwa region lives in large and medium towns of Punjab. More than 50% lives in large towns. Malwa region is agriculturally very prosperous area. So Mandi towns are well distributed throughout the region. Keywords: Growth, Urban, Population, Development. I. INTRODUCTION The distribution of urban population and its growth reflect the economic structure of population as well as economic growth of the region. The urban centers have different socio economic value systems, degree of socio-economic awakening than the rural areas. Although Urbanisation is an inescapable process and is related to the economic growth of the region but regional imbalances in urbanization creates problems for Planners so urban growth need to be channelized in planned manner and desired direction. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

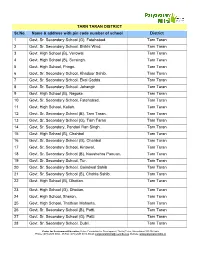

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

1. Introduction “Bhand-Marasi”

1. INTRODUCTION “BHAND-MARASI” A Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre Bhand-Marasi is a Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre. My project is based on Punjabi folk-forms. I am unable to work on all the existing folk-forms of Punjab because of limited budget & time span. By taking in concern the current situation of the Punjabi folk theatre, I together with my whole group, strongly feel that we should put some effort in preventing this particular folk-form from being extinct. Bhand-Marasi had been one of the chief folk-form of celebration in Punjabi culture. Nowadays, people don’t have much time to plan longer celebrations at homes since the concept of marriage palaces & banquet halls has arrived & is in vogue these days to celebrate any occasion in the family. Earlier, these Bhand-Marasis used to reach people’s home after they would get the wind of any auspicious tiding & perform in their courtyard; singing holy song, dancing, mimic, becoming characters of the host family & making or enacting funny stories about these family members & to wind up they would pray for the family’s well-being. But in the present era, their job of entertaining the people has been seized by the local orchestra people. Thus, the successors of these Bhand- Marasis are forced to look for other jobs for their living. 2. OBJECTIVE At present, we feel the need of “Data- Creation” of this Folk Theatre-Form of Punjab. Three regions of Punjab Majha, Malwa & Doaba differ in dialect, accent & in the folk-culture as well & this leads to the visible difference in the folk-forms of these regions. -

Militancy and Media: a Case Study of Indian Punjab

Militancy and Media: A case study of Indian Punjab Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab for the award of Master of Philosophy in Centre for South and Central Asian Studies By Dinesh Bassi Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. V.J Varghese Administrative Supervisor: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 2012 June DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. V. J. Varghese, Assistant Professor, Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, and administrative supervision of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Dean, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Dinesh Bassi) Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: 5th June, 2012 ii CERTIFICATE We certify that Dinesh Bassi has prepared his dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB for the award of M.Phil. Degree under our supervision. He has carried out this work at the Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. V. J. Varghese) Assistant Professor Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Dean Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

Punjab Board Class 9 Social Science Textbook Part 1 English

SOCIAL SCIENCE-IX PART-I PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION BOARD Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar © Punjab Government First Edition : 2018............................ 38406 Copies All rights, including those of translation, reproduction and annotation etc., are reserved by the Punjab Government. Editor & Co-ordinator Geography : Sh. Raminderjit Singh Wasu, Deputy Director (Open School), Punjab School Education Board. Economics : Smt. Amarjit Kaur Dalam, Deputy Director (Academic), Punjab School Education Board. WARNING 1. The Agency-holders shall not add any extra binding with a view to charge extra money for the binding. (Ref. Cl. No. 7 of agreement with Agency-holders). 2. Printing, Publishing, Stocking, Holding or Selling etc., of spurious Text- book qua text-books printed and published by the Punjab School Education Board is a cognizable offence under Indian Penal Code. Price : ` 106.00/- Published by : Secretary, Punjab School Education Board, Vidya Bhawan Phase-VIII, Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar-160062. & Printed by Tania Graphics, Sarabha Nagar, Jalandhar City (ii) FOREWORD Punjab School Education Board, has been engaged in the endeavour to prepare textbooks for all the classes at school level. The book in hand is one in the series and has been prepared for the students of class IX. Punjab Curriculum Framework (PCF) 2013 which is based on National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005, recommends that the child’s life at school must be linked to their life outside the school. The syllabi and textbook in hand is developed on the basis of the principle which makes a departure from the legacy of bookish learning to activity-based learning in the direction of child-centred system. -

Electoral Politics in Punjab : from Autonomy to Secession

ELECTORAL POLITICS IN PUNJAB : FROM AUTONOMY TO SECESSION Fifty years of electoral history of Punjab has been intermeshed with issues relating to competing identities, regional autonomy and the political perception of threat and need paradox of democratic institutions. These issues together or separately have influenced the dynamics of electoral politics. The articulation of these issues in various elections has been influenced by the socio-economic and political context. Not only this, even the relevance of elections has depended on its capacity to seek resolution of conflicts emanating from interactive relationship of these factors. These broad boundaries found expression in electoral discourse in four distinct phases i.e. pre- reorganisation from 1947 to 1966, reorganisation phase from 1966 to 1980, terrorism phase from 1980 and 1992 and post-terrorism from 1992 onwards. Historically, social mobilisations and political articulation have also taken diverse forms. These assertions can be categorised under three main headings, i.e. communal, caste or religion; secular or strata based. All these competing identities have been co-existing. For instance, Punjab had, a culture and a language which transcended religious group boundaries, a unified politico-administrative unit and specialised modern technology, which initiated the integration process of the diverse religious, caste and other ascriptive group identities. Inspite of the historical process of formulation and reformulation of the composite linguistic cultural consciousness, the tendency to evolve a unified sub-nationality with a common urge for territorial integrity remained weak in Punjab. On the contrary, politics mobilised people along communal lines resulting in the partition in 1947 and division in 1966 of the Punjabi speaking people. -

A Review on Notorious Identity of Malwa Region of Punjab: Cancer Belt

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 180-183 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 A review on notorious identity of Malwa region of IJAR 2016; 2(2): 180-183 www.allresearchjournal.com Punjab: Cancer belt Received: 05-12-2015 Accepted: 08-01-2016 Neeraj Godara Neeraj Godara Department of chemistry DAV College Abohar Punjab, India Abstract The immoderate exploitation of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, diffusion of heavy metals in groundwater, industrial waste leading to river water pollution turned out to be the major causes of cancer in Malwa region of Punjab. The exorbitant treatment of cancer and the lack of facilities in civil hospitals in Punjab force the patients from Punjab to approach the Acharya Tulsi Das Regional Cancer Centre, Bikaner in Rajasthan state via infamous ‘cancer train’ for getting aided treatment at economical rates. Although, many initiatives have been taken by the state government such as establishment of RO systems inillages, testing of heavy metals in groundwater, undertaking of health education activities to aware the people regarding the signs, symptoms and prevention of cancer, control on excessive use of chemicals on crops, Mukh Mantri Cancer Rahat Kosh Scheme and cancer registry system but much more is needed to be done to prevent the nuisance. Keywords: notorious, exploitation, pesticides, establishment 1. Introduction Punjab as an agrarian economy has gained the benefits of agricultural development, but it has to pay the price for this development. Green Revolution undoubtedly transformed Indian Economy from food importing to food exporting economy and Punjab got honour of the bread basket of India. -

Water Table Behaviour in Punjab: Issues and Policy Options

WATER TABLE BEHAVIOUR IN PUNJAB: ISSUES AND POLICY OPTIONS Karam Singh* Abstract Punjab faces a sever problem of declining water tables by as much as 10 – 15m in most parts. The paper focuses on groundwater behavior in various parts (Blocks) of the Punjab in categories of low to high rainfall regions, saline to sweet groundwater zones, scanty to extensive canal water supply areas, the uplands to riverbeds and the cropping pattern in terms of low to high water intensive crops. Any changes in these parameters will affect the recharge and withdrawal of groundwater. In was found that as the area under rice cultivation increased, there was a corresponding decline in ground water recharge. It is often advocated that pricing policy for wheat and rice (Minimum Support Price (MSP) and its effectiveness) and free electricity supply are responsible for the critical ground water situation in Punjab. The paper tires to examine this and look at policy measures needed to address the situation. 1. INTRODUCTION The groundwater situation in Punjab has been a serious issue for a long time now. The total water requirement for Punjab, with the present cropping pattern and practices and industrial uses, is estimated at 4.33 million ha metres. It varies from 4.30 to 4.40 million ha metres. The total availability of water is estimated at 3.13 million ha metres out of which 1.45 million ha meters is from canals and 1.68 ha meters is from rainfall and seepage. The deficit of almost 1.20 million ha metres is met by ground water withdrawal. -

Hoshiarpur District, Vol-8 , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951 PUNJAB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS Volume 8 HOSHIARPUR DISTRICT COMPILED & PUBLISHED UNDER The Authority of the Punjab Government Printed by the Controller, Printing lind Stationary Punjab. at the Forward Block Prest. Simla. INDEX Serial~ I Table No. I Subject Page 1 Preface 2 Introduction:- (a) Physical Aspects· 1 (b) Geology 3 (c) Archaeology 4 (d) Climate ib (e) Rain fall 5 (f) History ih (g) Population 6 (h) Administration 7 (i) Medical and Pnblio Health 8 (j) Education and Literacy ib (k) Agriculture a.nd Co· operation 9 (I) Industries ib (m) Local Bodies (n) Rehabilitation of Displaced 10 PersollB II (o) Places of Interest 12 3 Statement Explaning the Tables 21 4 A-I Area, Houses and Population jj 5 A·II Variation in population. during fiflly years vi 6 A-III Towns and Villages classified . by population :x: 7 A·IV Towns classified by population with xvi variation since 1901 8 A.V Towns arranged territorially with xx: population by livelihood cla8ses Livelihood classes and sub·cla.sst's ii (Total) B.I Livelihood classes and sub-classes viii (Displaced) 10 B.I1 Seondary means of .. livelihood x:iv (Total) ,. Secondary means of livelihood xxxviii (Displaced ) 11 B.llI Employers, Employees and lndepen. lxii dant workers (To\a.l' B·III Employers, Employees and Indepen- Ixxxviii ,dant workers (Displaced) I ii S;;ial I SUbjeot No. Table No Page 12 C-II • . Livelihood by age groups ( Displaced) ii 13 C·III Age and civil condition ( Displaced) ix 14 C.IV Age and literacy (Sample) xvii C~IV Age and literacy (Displaced) xx 15 D-ll Rehgion ii It} D-III Scheduled Castes and Scheduled 'l'ribes iii 17 D-IV Migrants iv D·IV Subsidiary viii lsi D-V Displaced persons by district of origin and date of arrival in India xi 19 D-VI Non-Indian Nationals xxix 20 D-Vn Livelihood classes by educational standards xxx 21 E Summary figures by District. -

Corruption and Factionalism in Contemporary Punjab: an Ethnographic Account from Rural Malwa

Modern Asian Studies 52, 3 (2018) pp. 942–970. C Cambridge University Press 2018 doi:10.1017/S0026749X1700004X Corruption and Factionalism in Contemporary Punjab: An ethnographic account from rural Malwa NICOLAS MARTIN Indology/Modern Indian Studies, Universitat Zurich Email: [email protected] Abstract Over the length of its current tenure, Punjab’s Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) has sought to become more a socially inclusive party, more responsive to popular demands, and even to improve service delivery and eradicate corruption. However, despite these lofty goals, it has also presided over what people refer to as ‘goonda raj’—a rule of thugs—and has managed to alienate large sections of the population and, in the process, fuelled the rise of the anti-corruption Aam Admi Party in the state. In this article, based on ethnographic fieldwork in rural Malwa, I attempt to shed light on the roots of this contradiction. Is it simply the case, as ordinary people allege, that the SAD’s claims are empty and that its members are merely interested in looting the state? Or, alternatively, is it the case that the party merely operates in accordance with Punjab’s allegedly time-honoured tradition of rival factions competing to appropriate the spoils of power? I suggest instead that much of the corruption and violence observable at the village level in Punjab has its roots in the antagonistic relationship between the Congress Party and the Shiromani Akali Dal. It is this antagonism that appears to fuel the SAD’s highly partisan form of government, and it is partisan government that appears to fuel the corruption and the village-level factional conflict that is documented in this article.