Electoral Politics in Punjab : from Autonomy to Secession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) Majha House, Amritsar August 30

IndiaFoundationfortheArts(IFA)incollaborationwithMajhaHouse,Amritsarpresents August30and31,2019 ConferenceHall,GuruNanakBhawan,GuruNanakDevUniversity MakkaSinghColony,Amritsar,Punjab143005 August30,2019 10:00AM-10:15AM:Inauguration 10:15AM-11:45AM:OutofThinAir (ShabaniHassanwalia&SamreenFarooqui|Hindi/EnglishwithEnglishsubtitles|50min) ShabaniHassanwaliawillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening 11:45AM-12:00PM:TeaBreak 12:00PM-01:15PM:LehKharyok (TashiMorup,LadakhArtsandMediaOrganisation|Ladakhi/EnglishwithEnglishsubtitles|59min) 01:15PM-02:15PM:Lunch 02:15PM-03:30PM:CityofPhotos (NishthaJain|Englishwithsubtitles|60min) 03:30PM-04:45PM:KitteMilVeMahi (AjayBharadwaj|PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|72min) 04:45PM-05:00PM:TeaBreak 05:00PM-06:30PM:Gali (SamreenFarooqui&ShabaniHassanwalia|Hindi/PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|52min) ShabaniHassanwaliawillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening August31,2019 10:15AM-11:45AM:KumarTalkies (PankajRishiKumar|HindiwithEnglishsubtitles|76min) 11:45AM-12:00PM:TeaBreak 12:00PM-01:30PM:TheNineMonths (MerajurRahmanBaruah|AssamesewithEnglishsubtitles|77min) 01:30PM-02:15PM:Lunch 02:15PM-03:30PM:I,Dance (SonyaFatahandRajivRao|English/Hindi/Urdu|60min) 03:30PM-05:00PM:Pala (GurvinderSingh|PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|83min) IFAFILMFESTIVAL 05:00PM-05:15PM:TeaBreak 05:15PM-06:30PM:TheCommonTask (PallaviPaul|English/HindiwithEnglishsubtitles|52min) PallaviPaulwillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening 06:30PM-07:00PM:ClosingRemarks AllthefilmsbeingscreenedhavebeensupportedbyIFA www.indiaifa.org /IndiaIFA GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)

Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Draft April 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Punjab Municipal Infrastructure Development Company, Department of Local Government, Government of Punjab Public Disclosure Authorized i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE ESMF .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................... 15 2.1 PROJECT COMPONENTS .................................................................................................................................... 15 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS AND IMPACTS................................................................................................................ -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab)

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2018 34 ISSN 2250-3153 Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab) Kamaljit Kaur DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 Abstract: This study deals with the spatial analysis of growth of urban population. Malwa region has been taken as a case study. During 1991-2001, the urban growth has been shown in Malwa region of Punjab. The large number of new towns has emerged in this region during 1991-2001 periods. Urban growth of Malwa region as well as distribution of urban centres is closely related to accessibility and modality factors. The large urban centres are located along major arteries. International border with an unfriendly neighbour hinders urban growth. It indicates that secondary activities have positive correlation with urban growth. More than 90% of urban population of Malwa region lives in large and medium towns of Punjab. More than 50% lives in large towns. Malwa region is agriculturally very prosperous area. So Mandi towns are well distributed throughout the region. Keywords: Growth, Urban, Population, Development. I. INTRODUCTION The distribution of urban population and its growth reflect the economic structure of population as well as economic growth of the region. The urban centers have different socio economic value systems, degree of socio-economic awakening than the rural areas. Although Urbanisation is an inescapable process and is related to the economic growth of the region but regional imbalances in urbanization creates problems for Planners so urban growth need to be channelized in planned manner and desired direction. -

Punjab: a Background

2. Punjab: A Background This chapter provides an account of Punjab’s Punjab witnessed important political changes over history. Important social and political changes are the last millennium. Its rulers from the 11th to the traced and the highs and lows of Punjab’s past 14th century were Turks. They were followed by are charted. To start with, the chapter surveys the Afghans in the 15th and 16th centuries, and by Punjab’s history up to the time India achieved the Mughals till the mid-18th century. The Sikhs Independence. Then there is a focus on the Green ruled over Punjab for over eighty years before the Revolution, which dramatically transformed advent of British rule in 1849. The policies of the Punjab’s economy, followed by a look at the Turko-Afghan, Mughal, Sikh and British rulers; and, tumultuous period of Naxalite-inspired militancy in the state. Subsequently, there is an account of the period of militancy in the state in the 1980s until its collapse in the early 1990s. These specific events and periods have been selected because they have left an indelible mark on the life of the people. Additionally, Punjab, like all other states of the country, is a land of three or four distinct regions. Often many of the state’s characteristics possess regional dimensions and many issues are strongly regional. Thus, the chapter ends with a comment on the regions of Punjab. History of Punjab The term ‘Punjab’ emerged during the Mughal period when the province of Lahore was enlarged to cover the whole of the Bist Jalandhar Doab and the upper portions of the remaining four doabs or interfluves. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

Song and Memory: “Singing from the Heart”

SONG AND MEMORY: “SINGING FROM THE HEART” hir kIriq swDsMgiq hY isir krmn kY krmw ] khu nwnk iqsu BieE prwpiq ijsu purb ilKy kw lhnw ]8] har kīrat sādhasangat hai sir karaman kai karamā || kahu nānak tis bhaiou parāpat jis purab likhē kā lahanā ||8|| Singing the Kīrtan of the Lord’s Praises in the Sādh Sangat, the Company of the Holy, is the highest of all actions. Says Nānak, he alone obtains it, who is pre-destined to receive it. (Sōrath, Gurū Arjan, AG, p. 641) The performance of devotional music in India has been an active, sonic conduit where spiritual identities are shaped and forged, and both history and mythology lived out and remembered daily. For the followers of Sikhism, congregational hymn singing has been the vehicle through which melody, text and ritual act as repositories of memory, elevating memory to a place where historical and social events can be reenacted and memorialized on levels of spiritual significance. Hymn-singing services form the magnetic core of Sikh gatherings. As an intimate part of Sikh life from birth to death, Śabad kīrtan’s rich kaleidoscope of singing and performance styles act as a musical and cognitive archive bringing to mind a collective memory, uniting community to a common past. As a research scholar and practitioner of Gurmat Sangīt, I have observed how hymn singing plays such a significant role in understanding the collective, communal and egalitarian nature of Sikhism. The majority of events that I attended during my research in Punjab involved congregational singing: whether seated in the Gūrdwāra, or walking in a procession, the congregants were often actively engaged in singing. -

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

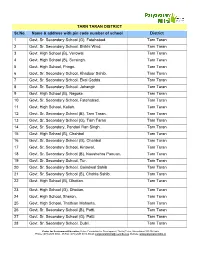

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

1. Introduction “Bhand-Marasi”

1. INTRODUCTION “BHAND-MARASI” A Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre Bhand-Marasi is a Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre. My project is based on Punjabi folk-forms. I am unable to work on all the existing folk-forms of Punjab because of limited budget & time span. By taking in concern the current situation of the Punjabi folk theatre, I together with my whole group, strongly feel that we should put some effort in preventing this particular folk-form from being extinct. Bhand-Marasi had been one of the chief folk-form of celebration in Punjabi culture. Nowadays, people don’t have much time to plan longer celebrations at homes since the concept of marriage palaces & banquet halls has arrived & is in vogue these days to celebrate any occasion in the family. Earlier, these Bhand-Marasis used to reach people’s home after they would get the wind of any auspicious tiding & perform in their courtyard; singing holy song, dancing, mimic, becoming characters of the host family & making or enacting funny stories about these family members & to wind up they would pray for the family’s well-being. But in the present era, their job of entertaining the people has been seized by the local orchestra people. Thus, the successors of these Bhand- Marasis are forced to look for other jobs for their living. 2. OBJECTIVE At present, we feel the need of “Data- Creation” of this Folk Theatre-Form of Punjab. Three regions of Punjab Majha, Malwa & Doaba differ in dialect, accent & in the folk-culture as well & this leads to the visible difference in the folk-forms of these regions. -

The Sikhs of the Punjab

“y o—J “ KHS OF TH E P U N J B Y R. E . P A RRY . Late Indian ArmyRes erve of Offic ers s ome time A ctin g C aptain and Adj utant z/15t-h Lu n i h me m t he 5th dhia a S k s . S o ti e at ac d 3 S s . ”D " do \ r LO ND O N D R A N E ' S , D ANEGELD H O U S E , 82 A F ARRINGD O N STREET C 4 E . , , . O N TE N TS C . P reface Chapter l— Religion and H is tory ’ 2 — Char acteri s tic s of the Jat 3— Sikh Vill ag e Life 4 — The E conomic Geography of the P unj ab ( i) The Contr ol of E nvir on 5 Agr icu ltu re and Indu s tri es G— Rec ruiting Methods Index Bibliography P RE F AGE . m Thi s little book is written with the obj ect of giving tothe general pu blic s ome idea of one of our mos t loyal I nd i an s ects ; thou gh its nu m er s ar e om ar a e few et b c p tiv ly , yit played nosmall share in u pholding the traditions of tli e Br iti sh E mpir e in nol es s than s ix theatres f w r 0 a . N otru e picture wou ld b e complet e with ou t s ome account of the envir onment that has ed t m the h r er h s help o ould Sik ch a act .