A Sikh Migrant in Shanghai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) Majha House, Amritsar August 30

IndiaFoundationfortheArts(IFA)incollaborationwithMajhaHouse,Amritsarpresents August30and31,2019 ConferenceHall,GuruNanakBhawan,GuruNanakDevUniversity MakkaSinghColony,Amritsar,Punjab143005 August30,2019 10:00AM-10:15AM:Inauguration 10:15AM-11:45AM:OutofThinAir (ShabaniHassanwalia&SamreenFarooqui|Hindi/EnglishwithEnglishsubtitles|50min) ShabaniHassanwaliawillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening 11:45AM-12:00PM:TeaBreak 12:00PM-01:15PM:LehKharyok (TashiMorup,LadakhArtsandMediaOrganisation|Ladakhi/EnglishwithEnglishsubtitles|59min) 01:15PM-02:15PM:Lunch 02:15PM-03:30PM:CityofPhotos (NishthaJain|Englishwithsubtitles|60min) 03:30PM-04:45PM:KitteMilVeMahi (AjayBharadwaj|PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|72min) 04:45PM-05:00PM:TeaBreak 05:00PM-06:30PM:Gali (SamreenFarooqui&ShabaniHassanwalia|Hindi/PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|52min) ShabaniHassanwaliawillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening August31,2019 10:15AM-11:45AM:KumarTalkies (PankajRishiKumar|HindiwithEnglishsubtitles|76min) 11:45AM-12:00PM:TeaBreak 12:00PM-01:30PM:TheNineMonths (MerajurRahmanBaruah|AssamesewithEnglishsubtitles|77min) 01:30PM-02:15PM:Lunch 02:15PM-03:30PM:I,Dance (SonyaFatahandRajivRao|English/Hindi/Urdu|60min) 03:30PM-05:00PM:Pala (GurvinderSingh|PunjabiwithEnglishsubtitles|83min) IFAFILMFESTIVAL 05:00PM-05:15PM:TeaBreak 05:15PM-06:30PM:TheCommonTask (PallaviPaul|English/HindiwithEnglishsubtitles|52min) PallaviPaulwillbepresentforaQ&Aafterthescreening 06:30PM-07:00PM:ClosingRemarks AllthefilmsbeingscreenedhavebeensupportedbyIFA www.indiaifa.org /IndiaIFA GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab)

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2018 34 ISSN 2250-3153 Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab) Kamaljit Kaur DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 Abstract: This study deals with the spatial analysis of growth of urban population. Malwa region has been taken as a case study. During 1991-2001, the urban growth has been shown in Malwa region of Punjab. The large number of new towns has emerged in this region during 1991-2001 periods. Urban growth of Malwa region as well as distribution of urban centres is closely related to accessibility and modality factors. The large urban centres are located along major arteries. International border with an unfriendly neighbour hinders urban growth. It indicates that secondary activities have positive correlation with urban growth. More than 90% of urban population of Malwa region lives in large and medium towns of Punjab. More than 50% lives in large towns. Malwa region is agriculturally very prosperous area. So Mandi towns are well distributed throughout the region. Keywords: Growth, Urban, Population, Development. I. INTRODUCTION The distribution of urban population and its growth reflect the economic structure of population as well as economic growth of the region. The urban centers have different socio economic value systems, degree of socio-economic awakening than the rural areas. Although Urbanisation is an inescapable process and is related to the economic growth of the region but regional imbalances in urbanization creates problems for Planners so urban growth need to be channelized in planned manner and desired direction. -

Punjab: a Background

2. Punjab: A Background This chapter provides an account of Punjab’s Punjab witnessed important political changes over history. Important social and political changes are the last millennium. Its rulers from the 11th to the traced and the highs and lows of Punjab’s past 14th century were Turks. They were followed by are charted. To start with, the chapter surveys the Afghans in the 15th and 16th centuries, and by Punjab’s history up to the time India achieved the Mughals till the mid-18th century. The Sikhs Independence. Then there is a focus on the Green ruled over Punjab for over eighty years before the Revolution, which dramatically transformed advent of British rule in 1849. The policies of the Punjab’s economy, followed by a look at the Turko-Afghan, Mughal, Sikh and British rulers; and, tumultuous period of Naxalite-inspired militancy in the state. Subsequently, there is an account of the period of militancy in the state in the 1980s until its collapse in the early 1990s. These specific events and periods have been selected because they have left an indelible mark on the life of the people. Additionally, Punjab, like all other states of the country, is a land of three or four distinct regions. Often many of the state’s characteristics possess regional dimensions and many issues are strongly regional. Thus, the chapter ends with a comment on the regions of Punjab. History of Punjab The term ‘Punjab’ emerged during the Mughal period when the province of Lahore was enlarged to cover the whole of the Bist Jalandhar Doab and the upper portions of the remaining four doabs or interfluves. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

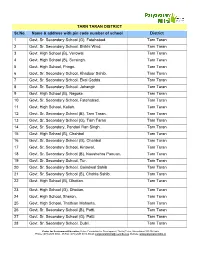

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

1. Introduction “Bhand-Marasi”

1. INTRODUCTION “BHAND-MARASI” A Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre Bhand-Marasi is a Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre. My project is based on Punjabi folk-forms. I am unable to work on all the existing folk-forms of Punjab because of limited budget & time span. By taking in concern the current situation of the Punjabi folk theatre, I together with my whole group, strongly feel that we should put some effort in preventing this particular folk-form from being extinct. Bhand-Marasi had been one of the chief folk-form of celebration in Punjabi culture. Nowadays, people don’t have much time to plan longer celebrations at homes since the concept of marriage palaces & banquet halls has arrived & is in vogue these days to celebrate any occasion in the family. Earlier, these Bhand-Marasis used to reach people’s home after they would get the wind of any auspicious tiding & perform in their courtyard; singing holy song, dancing, mimic, becoming characters of the host family & making or enacting funny stories about these family members & to wind up they would pray for the family’s well-being. But in the present era, their job of entertaining the people has been seized by the local orchestra people. Thus, the successors of these Bhand- Marasis are forced to look for other jobs for their living. 2. OBJECTIVE At present, we feel the need of “Data- Creation” of this Folk Theatre-Form of Punjab. Three regions of Punjab Majha, Malwa & Doaba differ in dialect, accent & in the folk-culture as well & this leads to the visible difference in the folk-forms of these regions. -

Militancy and Media: a Case Study of Indian Punjab

Militancy and Media: A case study of Indian Punjab Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab for the award of Master of Philosophy in Centre for South and Central Asian Studies By Dinesh Bassi Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. V.J Varghese Administrative Supervisor: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 2012 June DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. V. J. Varghese, Assistant Professor, Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, and administrative supervision of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Dean, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Dinesh Bassi) Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: 5th June, 2012 ii CERTIFICATE We certify that Dinesh Bassi has prepared his dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB for the award of M.Phil. Degree under our supervision. He has carried out this work at the Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. V. J. Varghese) Assistant Professor Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Dean Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

Changing Caste Relations and Emerging Contestations in Punjab

CHANGING CASTE RELATIONS AND EMERGING CONTESTATIONS IN PUNJAB PARAMJIT S. JUDGE When scholars and political leaders characterised Indian society as unity in diversity, there were simultaneous efforts in imagining India as a civilisational unity also. The consequences of this ‘imagination’ are before us in the form of the emergence of religious nationalism that ultimately culminated into the partition of the country. Why have I started my discussion with the issue of religious nationalism and partition? The reason is simple. Once we assume that a society like India could be characterised in terms of one caste hierarchical system, we are essentially constructing the discourse of dominant Hindu civilisational unity. Unlike class and gender hierarchies which are exist on economic and sexual bases respectively, all castes cannot be aggregated and arranged in hierarchy along one axis. Any attempt at doing so would amount to the construction of India as essentially the Hindu India. Added to this issue is the second dimension of hierarchy, which could be seen by separating Varna from caste. Srinivas (1977) points out that Varna is fixed, whereas caste is dynamic. Numerous castes comprise each Varna, the exception to which is the Brahmin caste whose caste differences remain within the caste and are unknown to others. We hardly know how to distinguish among different castes of Brahmins, because there is complete absence of knowledge about various castes among them. On the other hand, there is detailed information available about all the scheduled castes and backward classes. In other words, knowledge about castes and their place in the stratification system is pre- determined by the enumerating agency. -

Differences of Domain-Specific Physical Activity Levels

International Journal of Current Research and Review Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31782/IJCRR.2021.13602 Differences of Domain-specific Physical Activity Levels among the Adults of Majha Region of Indian IJCRR Punjab: A Cross-sectional Study Section: Healthcare ISI Impact Factor (2019-20): 1.628 1 2 3 4 IC Value (2019): 90.81 Harmandeep Singh , Sukhdev Singh , Amandeep Singh , Tarsem Singh , SJIF (2020) = 7.893 Vikesh Kumar5 1 2 Copyright@IJCRR Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Education, Apeejay College of Fine Arts, Jalandhar, India; Professor & Head, Department of Physical Education (T), Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, India; 3Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Education (T), Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, India; 4Associate Professor, Department of Physical Education, Lyallpur Khalsa College, Jalandhar, India; 5Director, Physical Education, Government Degree College Jindrah, Jammu & Kashmir, India. ABSTRACT Background: Regular participation in physical activity is essential to attain health benefits. Previous studies have stressed to consider domains of physical activity while assessing the physical activity levels across the different sections of the populations. Objective: To assess the differences in physical activity levels between males and females of the Majha region of Indian Punjab. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted including the four districts of the Majha region of Indian Punjab. A total of 1130 participants including 628 females and 502 males were interviewed using the WHO-recommended Global Physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). Physical activity was assessed in three domains viz. work, transport and recreational. Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare the non-parametric data of physical activity levels. -

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Dr Jagraj Singh A publication of Sikh University USA Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 1 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A comparative study of Sikhism and Hinduism Contents Page Acknowledgements 4 Foreword Introduction 5 Chapter 1 What is Sikhism? 9 What is Hinduism? 29 Who are Sikhs? 30 Who are Hindus? 33 Who is a Sikh? 34 Who is a Hindu? 35 Chapter 2 God in Sikhism. 48 God in Hinduism. 49 Chapter 3 Theory of creation of universe---Cosmology according to Sikhism. 58 Theory of creation according to Hinduism 62 Chapter 4 Scriptures of Sikhism 64 Scriptures of Hinduism 66 Chapter 5 Sikh place of worship and worship in Sikhism 73 Hindu place of worship and worship in Hinduism 75 Sign of invocation used in Hinduism Sign of invocation used in Sikhism Chapter 6 Hindu Ritualism (Karm Kanda) and Sikh view 76 Chapter 7 Important places of Hindu pilgrimage in India 94 Chapter 8 Hindu Festivals 95 Sikh Festivals Chapter 9 Philosophy of Hinduism---Khat Darsan 98 Philosophy of Sikhism-----Gur Darshan / Gurmat 99 Chapter 10 Panjabi language 103 Chapter 11 The devisive caste system of Hinduism and its rejection by Sikhism 111 Chapter 12 Religion and Character in Sikhism------Ethics of Sikhism 115 Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 2 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Sexual morality in Sikhism Sexual morality in Hinduism Religion and ethics of Hinduism Status of woman in Hinduism Chapter13 Various concepts of Hinduism and the Sikh view 127 Chapter 14 Rejection of authority of scriptures of Hinduism by Sikhism 133 Chapter 15 Sacraments of Hinduism and Sikh view 135 Chapter 16 Yoga (Yogic Philosophy of Hinduism and its rejection in Sikhism 142 Chapter 17 Hindu mythology and Sikh view 145 Chapter 18 Un-Sikh and anti-Sikh practices and their rejection 147 Chapter 19 Sikhism versus other religious aystems 149 Glossary of common terms used in Sikhism 154 Bibliography 160 Copyright Dr.