Building Bonn: Democracy and the Architecture of Humility by Philipp Nielsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal City and Centre of International Cooperation

Bonn Federal City and Centre of International Cooperation Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor of Bonn 2 Content Bonn – a New Profile 4 Bonn – City of the German Constitution 12 The Federal City of Bonn – Germany’s Second Political Centre 14 International Bonn – Working Towards sustainable Development Worldwide 18 Experience Democracy 28 Bonn – Livable City and Cultural Centre 36 1 Foreword to show you that Bonn’s 320,000 inhabitants may make it a comparatively small town, but it is far from being small-town. On the contrary, Bonn is the city of tomor- “Freude.Joy.Joie.Bonn” – row, where the United Nations, as well as science and Bonn’s logo says everything business, explore the issues that will affect humankind in about the city and is based on the future. Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Bonn’s logo, “Freude.Joy.Joie.Bonn.”, incidentally also Joy”, made immortal by our stands for the cheerful Rhenish way of life, our joie de vi- most famous son, Ludwig van vre or Lebensfreude as we call it. Come and experience it Beethoven, in the final choral yourself: Sit in our cafés and beer gardens, go jogging or movement of his 9th Symphony. “All men shall be brot- cycling along the Rhine, run through the forests, stroll hers” stands for freedom and peaceful coexistence in the down the shopping streets and alleys. View the UN and world, values that are also associated with Bonn. The city Post Towers, Godesburg Castle and the scenic Siebenge- is the cradle of the most successful democracy on Ger- birge, the gateway to the romantic Rhine. -

Deutschland 83 Is Determined to Stake out His Very Own Territory

October 3, 1990 – October 3, 2015. A German Silver Wedding A global local newspaper in cooperation with 2015 Share the spirit, join the Ode, you’re invited to sing along! Joy, bright spark of divinity, Daughter of Elysium, fire-inspired we tread, thy Heavenly, thy sanctuary. Thy magic power re-unites all that custom has divided, all men become brothers under the sway of thy gentle wings. 25 years ago, world history was rewritten. Germany was unified again, after four decades of separation. October 3 – A day to celebrate! How is Germany doing today and where does it want to go? 2 2015 EDITORIAL Good neighbors We aim to be and to become a nation of good neighbors both at home and abroad. WE ARE So spoke Willy Brandt in his first declaration as German Chancellor on Oct. 28, 1969. And 46 years later – in October 2015 – we can establish that Germany has indeed become a nation of good neighbors. In recent weeks espe- cially, we have demonstrated this by welcoming so many people seeking GRATEFUL protection from violence and suffer- ing. Willy Brandt’s approach formed the basis of a policy of peace and détente, which by 1989 dissolved Joy at the Fall of the Wall and German Reunification was the confrontation between East and West and enabled Chancellor greatest in Berlin. The two parts of the city have grown Helmut Kohl to bring about the reuni- fication of Germany in 1990. together as one | By Michael Müller And now we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of our unity regained. -

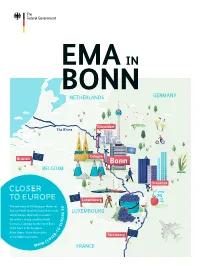

Closer to Europe — Tremendous Opportunities Close By: Germany Is Applying Interview – a Conversation with Bfarm Executive Director Prof

CLOSER TO EUROPE The new home of the European Medicines U E Agency (EMA) should be located centrally . E within Europe. Optimally accessible. P Set within a strong neigh bourhood. O R Germany is applying for the city of Bonn, U E at the heart of the European - O T Rhine Region, to be the location - R E of the EMA’s new home. S LO .C › WWW FOREWORD e — Federal Min öh iste Gr r o nn f H a e rm al e th CLOSER H TO EUROPE The German application is for a very European location: he EU 27 will encounter policy challenges Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The Institute Bonn. A city in the heart of Europe. Extremely close due to Brexit, in healthcare as in other ar- for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care located in T eas. A new site for the European Medicines nearby Cologne is Europe’s leading institution for ev- to Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. Agency (EMA) must be found. Within the idence-based drug evaluation. The Paul Ehrlich Insti- Situated within the tri-state nexus of North Rhine- EU, the organisation has become the primary centre for tute, which has 800 staff members and is located a mere drug safety – and therefore patient safety. hour and a half away from Bonn, contributes specific, Westphalia, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. This is internationally acclaimed expertise on approvals and where the idea of a European Rhine Region has come to The EMA depends on close cooperation with nation- batch testing of biomedical pharmaceuticals and in re- life. -

Die Kanzlerwohnung – Ein Blick Hinter Die Kulissen Als Bundestag Und

Die Kanzlerwohnung – Ein Blick hinter die Kulissen Als Bundestag und Bundesregierung noch in Bonn beheimatet waren, wusste so gut wie jeder, wo der amtierende Bundeskanzler wohnt: Im Kanzlerbungalow, den Bundeskanzler Ludwig Erhard 1964 im Park des damaligen Bundeskanzleramts, des Palais Schaumburg, errichten ließ. Sein Vorgänger im Amt, Konrad Adenauer, blieb Zeit seiner Kanzlerschaft in seinem Haus im nahegelegenen Rhöndorf wohnen. Seit dem Umzug unseres Parlaments und eines Großteils der Regierungsbehörden nach Berlin sind mittlerweile gut 15 Jahre vergangen und die ehemalige Dienstwohnung unserer Regierungschefs steht nun interessierten Besuchern am Wochenende zur Besichtigung offen. Und in Berlin, gibt es dort auch eine Kanzlerwohnung? Kurz und knapp, es gibt keine offizielle Unterkunft für den deutschen Bundeskanzler in Berlin. Anfangs war zwar geplant, im Garten des heutigen Bundeskanzleramts auch einen Bungalow im Stil des Bonner Dienstsitzes zu errichten, es fehlte jedoch das nötige Geld, um ihn zu bauen. Seitdem wird die Freifläche vor allem als Hubschrauberlandeplatz für den jeweiligen Bundeskanzler genutzt. Alt-Bundeskanzler Gerhard Schröder entschied sich dazu, während der Arbeitswochen in Berlin in einem extra für ihn als Wohnung eingerichteten Teil des achten Stocks des Kanzleramts zu übernachten. Es war wirklich keine luxuriöse Unterkunft, die dem damaligen Bundeskanzler zur Verfügung stand. Mit insgesamt gerade einmal 28 Quadratmetern, einem Schlafzimmer – in das mit Müh und Not ein Bett hineinpasste –, einem zum Kleiderschrank umfunktionierten Badezimmer und mit an einer Seite der Wohnung spitz zulaufenden Wänden war die Behausung alles andere als komfortabel. Auch die Lage von Küche und Badezimmer trug nicht zur Steigerung des Wohlfühlfaktors bei. Um sie zu erreichen, musste man zuerst zwei große Konferenzräume durchqueren, die die „Wohnung“ in der Mitte teilten. -

Resume Moses July 2020

A. Dirk Moses Department of History University of North Carolina 554A Hamilton Hall 102 Emerson Dr., CB #3195 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3195 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dirkmoses.com ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Frank Porter Graham Distinguished Professor of Global Human Rights History, University of North Carolina, July 2020 Lecturer (later Professor of Modern History), University of Sydney, 2000-2010, 2016-2020 Professor of Global and Colonial History, European University Institute, Florence, 2011–2015. Research Fellow, Department of History, University of Freiburg, 1999–2000. EDUCATION Ph.D. Modern European History, University of California, Berkeley, USA, 1994–2000. M.A. Modern European History, University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, 1992–1994. M.Phil. Early Modern European History, University of St. Andrews, Scotland, 1988–1989. B.A. History, Government, and Law, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 1985–1987. FELLOWSHIPS, PRIZES, VISITING PROFESSORSHIPS Ina Levine Invitational Senior Scholar, Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, Washington, DC, 2019-2020. Declined. Senior Fellow, Lichtenberg Kolleg, University of Göttingen, October 2019 – February 2020. University of Sydney-WZB Berlin Social Science Center Exchange Program, September-October 2019. Visiting Professorship, Department of History, University of Pennsylvania, January-June 2019. Visiting Fellow, Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen/Institute for Human Sciences, Vienna, November 2017-February 2018. Declined. Visiting Professor, Haifa Center for German and European Studies, University of Haifa, May 2013. Membership, Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, January–April 2011. Declined. Australian Scholar Fellowship, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC, October-December 2010. Visiting Senior Fellow, Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies, August-September 2010. Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Human Rights, Columbia University, September- November 2009. -

“Antisemitism Is a Barometer of Democracy”

“ANTISEMITISM IS A BAROMETER OF DEMOCRACY”: CONFRONTING THE NAZI PAST IN THE WEST GERMAN ‘SWASTIKA EPIDEMIC’, 1959-1960 by Alan Jones Bachelor of Arts, University of New Brunswick, 2017 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Lisa Todd, PhD, History Examining Board: Gary Waite, PhD, History, Chair Sean Kennedy, PhD, History Jason Bell, PhD, Philosophy This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2019 ©Alan Jones, 2019 Abstract The vandalism of a synagogue in Cologne, West Germany on Christmas Day 1959 by two men in their mid-twenties sparked a wave of Antisemitic and Nazi vandalism across West Germany and the Western world. The “swastika epidemic,” as it came to be known, ignited serious debates surrounding public memory of the Second World War in Germany, and the extent to which West Germany had dealt with its Nazi past. The swastika epidemic became a powerful example of what critics at the time argued was the failure of West Germany to properly confront its Nazi past through the reconstruction policies of Konrad Adenauer. This thesis examines the reactions of West Germany’s government, led by Konrad Adenauer, to the swastika epidemic and its place in the shifting narratives of memory in the postwar era. Adenauer’s reactions to the epidemic were steeped in the status quo memory narratives of the preceding decade which would be increasingly challenged throughout the 1960s. ii Acknowledgements There are several organizations without whose help I would not have been able to finish this thesis. -

"Ein Mächtiger Pfeiler Im Bau Der Bundesrepublik". Das Gesetz Über

REINHARD SCHIFFERS „EIN MÄCHTIGER PFEILER IM BAU DER BUNDESREPUBLIK" Das Gesetz über das Bundesverfassungsgericht vom 12. März 1951* I. Bestimmungen über das Bundesverfassungsgericht im Grundgesetz 1. Vorschläge für eine Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit in den Jahren 1946 bis 1948. Die im internationalen Vergleich ungewöhnliche Aufgabenfülle des Bundesverfas sungsgerichts (im folgenden BVerfG) und sein hohes Ansehen bei der Bevölkerung lassen leicht vergessen, daß dieses Gericht sozusagen ein verspätetes Verfassungsor gan ist. Es steht zwar gleichberechtigt neben den anderen obersten Bundesorganen, also neben Bundestag, Bundesrat, Bundespräsident und Bundesregierung1, ist aber anders als diese Organe nicht mit der Gründung der Bundesrepublik ins Leben getre ten, sondern erst zwei Jahre später, am 28. September 19512. Zunächst mußten Parla ment und Regierung die gesetzliche Grundlage für die Errichtung des Gerichtes schaffen: das Gesetz über das Bundesverfassungsgericht vom 12.März 19513 (BVerfGG), dessen Entstehung4 die bald erscheinende Edition dokumentieren soll. Erst mit diesem Gesetz wurde das Institutionengefüge der Bundesrepublik vervoll ständigt. Der Hinweis, daß mit diesem Gesetz der Staatsaufbau der Bundesrepublik * Der vorliegende Beitrag wird in erweiterter Form die Einleitung zu der Edition „Grundlegung der Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit. Das Gesetz über das Bundesverfassungsgericht vom 12. März 1951" bil den, die von der Kommission für Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien in Bonn veröffentlicht wird: Quellen zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien, 4. Reihe „Deutschland seit 1945", Bd. 2, hrsg. von Karl Dietrich Bracher, Rudolf Morsey und Hans- Peter Schwarz, Düsseldorf 1984. - Wenn in den Fußnoten dieses Beitrags zitiert wird: „Dok. Nr." (mit der jeweiligen Ziffer), so handelt es sich um Verweise auf Dokumente, die in der erwähnten Edi tion abgedruckt werden. -

CDU) SOZIALORDNUNG: Dr

g Z 8398 C 'nformationsdienst der Christlich Demokratischen Union Deutschlands Union in Deutschland Bonn, den 7. Oktober 1982 Für die Wir packen Auftakt-Aktion Bundeskanzler es an Helmut Kohl liegen jetzt sämtliche Materia- Als Helmut Kohl vor zehn Tagen zum Bundes- lien vor. Ausführliche Vorstel- lung mit Abbildungen und Be- kanzler gewählt wurde, sagte er: „Packen wir es stellformular im rosa Teil. gemeinsam an." Dieses Wort gilt. Die Re- Von dem am 1. Oktober 1982 gierung unter seiner Führung hat angepackt. aktuell herausgegebenen „Zur D'e Bürger im Land spüren dies, sie atmen Sache"-Flugblatt zur Wahl Hel- *uf, daß die Zeit der Führungslosigkeit, des mut Kohls wurden am Wo- Tr chenende bereits über 3 Mil- eibenlassens und der Resignation zu Ende lionen Exemplare verteilt. 9eht. Auch die Beziehungen zu unseren Freun- • den im Ausland hat Helmut Kohl mit seinen er- sten Reisen nach Paris und Brüssel gefestigt Das traurige Erbe und gestärkt. Dokumentation über die Hin- terlassenschaft der Regierung Der Bundeskanzler und alle, die ihm helfen, haben in Schmidt im grünen Teil den letzten Tagen mit einem gewaltigen Arbeitspen- sum ein Beispiel für uns alle dafür gegeben, was jetzt yon uns verlangt wird, um Schritt für Schritt das trau- • HELMUT KOHL r,9e Erbe, das die Schmidt-Regierung hinterlassen Wir müssen den Leistungswillen nat, zu überwinden. Die häßliche Hetzkampagne zahl- in unserem Volke wieder beleben Seite 3 reicher Sozialdemokraten gegen diesen Neuanfang 2ßigt ihre Ohnmacht und ihr schlechtes Gewissen; s'e sind schlechte Verlierer und schlechte Demokra- • BUNDESTAGS- ten, und sie werden dafür am 6. März die Quittung er- FRAKTION halten. -

The Origins of Chancellor Democracy and the Transformation of the German Democratic Paradigm

01-Mommsen 7/24/07 4:38 PM Page 7 The Origins of Chancellor Democracy and the Transformation of the German Democratic Paradigm Hans Mommsen History, Ruhr University Bochum The main focus of the articles presented in this special issue is the international dimension of post World War II German politics and the specific role filled by the first West German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer. Adenauer’s main goal was the integration of the emerg- ing West German state into the West European community, while the reunification of Germany was postponed. In his view, any restoration of the former German Reich depended upon the cre- ation of a stable democratic order in West Germany. Undoubtedly, Adenauer contributed in many respects to the unexpectedly rapid rise of West Germany towards a stable parliamentary democratic system—even if most of the credit must go to the Western Allies who had introduced democratic structures first on the state level, and later on paved the way to the establishment of the Federal Republic with the fusion of the Western zones and the installment of the Economic Council in 1948. Besides the “economic miracle,” a fundamental shift within the West German political culture occurred, which gradually overcame the mentalities and prejudices of the late Weimar years that had been reactivated during the immediate aftermath of the war. While the concept of a specific “German path” (Sonderweg) had been more or less eroded under the impact of the defeat of the Nazi regime, the inherited apprehensiveness toward Western political traditions, symptomatic of the constitutional concepts of the German bourgeois resistance against Hitler, began to be replaced by an increasingly German Politics and Society, Issue 82 Vol. -

Building a Social Democratic Hall of Fame

Peter Merseburger. Willy Brandt 1913-1992: Visionär und Realist. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2002. 927 S. EUR 32.00, gebunden, ISBN 978-3-421-05328-2. Martin Rupps. Helmut Schmidt: Eine politische Biographie. Stuttgart: Hohenheim Verlag, 2002. 488 S. EUR 24.00, broschiert, ISBN 978-3-89850-073-9. Michael Schwelien. Helmut Schmidt: Ein Leben fÖ¼r den Frieden. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 2003. 368 pp. EUR 22.90, cloth, ISBN 978-3-455-09409-1. Hartmut Soell. Helmut Schmidt: Macht und Verantwortung. 1969 bis heute. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2008. 1082 S. EUR 39.90, broschiert, ISBN 978-3-421-05352-7. H-Net Reviews Bundeskanzler Willy Brandt Stiftung, ed.. Die Entspannung unzerstÖ¶rbar machen: Internationale Beziehungen und deutsche Frage, 1974-1982. Bonn: Dietz, 2003. 500 pp. EUR 27.60, cloth, ISBN 978-3-8012-0309-2. Reviewed by Ronald J. Granieri Published on H-German (October, 2005) In a democratic society, the passing of a politi‐ tivated. Not all of the scholars involved are active cal generation is always fascinating to watch, partisans, but there is an interesting congruence since it usually happens in multiple stages on between the cycles of politics and the politics of both a political and historical level. First, the old historical production. politicians leave the active political scene and are In Germany, the models for this process in‐ replaced by a new group of leaders. More often clude Helmut Kohl, who rebuilt the CDU after the than not, if the older politicians did great things, retirement of Konrad Adenauer and the failure of the successors, seeking in distance from their im‐ the immediate successors, and, more recently, mediate predecessors a surer way to their own Gerhard Schröder, who took a SPD rent by inter‐ path, run from the past. -

Bundestagsdebatte Vom 23. Januar 1958

Gesprächskreis Geschichte Heft 81 Otto Dann Eine Sternstunde des Bundestages Gustav Heinemanns Rede am 23. Januar 1958 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Historisches Forschungszentrum Herausgegeben von Michael Schneider Historisches Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Kostenloser Bezug beim Historischen Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Godesberger Allee 149, D-53175 Bonn Tel. 0228-883473 E-mail: [email protected] http://library.fes.de/history/pub-history.html © 2008 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn (-Bad Godesberg) Titelfoto: dpa/picture-alliance, Frankfurt/Main Foto: Der Spiegel, Hamburg Umschlag: Pellens Kommunikationsdesign GmbH, Bonn Druck: bub - Bonner Universitäts-Buchdruckerei, Bonn Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2008 ISBN 978-3-89892-931-8 ISSN 0941-6862 3 Inhalt Die Bundestags-Debatte vom 23. Januar 1958 ........................ .5 Gustav Heinemanns Rede ......................................................... 8 Resonanzen und Reaktionen ................................................... 13 Gustav Heinemann und Thomas Dehler ................................. 20 Der Weg in die SPD................................................................ 28 Gustav Heinemann in der SPD................................................ 33 Die Kampagne „Kampf dem Atomtod!“................................. 37 Deutschlandpläne .................................................................... 43 Ausblick: Godesberg............................................................... 48 Anhang ................................................................................... -

Security Versus Unity: Germany's Dilemma II

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT VORLD AFFAIRS DB- 8 Plockstrasse 8 Security versus Unity: Gie ssen, Germany Germany' s Dilemma II April l, 19G8 Mr. Walter S. Rogers Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue ew York 36, Eew York Dear Mr. Rogers: A few months before the -arch Bundestag debate on atomic weapons I Islted a local civil defense meeting. The group leader enthusiastically painted a hideous picture of atomic devastation; the audience remained dumb arid expressionless. Film and magazine reports on hydrogen bombs, fall-out, radiation effects they all seeme to fall on plugged ears in Germany. "at can one do?"'asked Kurt Odrig, who sells me vegetables. "Yhen it comes, we're all goers anyway." The Germans were not uique in that attitude. Along with this nuclear numbness there was the dazed resignation towards the question of reunification. Everybody was for it like the fiv cent clgar. Any West German politlclan who wanted to make the rade had to master the sacred roeunification phase: "Let us not forget our seventeen-million German brothe.,,_s over there..." Uttered ith solen reverence, it had an effect tho same as ,'poor starving rmenlans" ,once had paralysis. The Test Germans felt, rightly so, that there ,sn't much they could do about uifying their country. But since the arch debate their ,reaction to atoms and reunificatoa has changed from palsy to St. Vitus Dance. Germany's basic dilemma has not changed since 1949 security could not be had without sending reunifi- cation a begging; reunification could not be had without sacrificing security.