Gardiner Lake Shore Corridor Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Particular Concentration Between Beaconsfield Avenue and The

HISTORY AND EVOLUTION Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), the facility a particular concentration between Beaconsfield Avenue continues to influence the character of the area through and the Queen Street West Subway. These have coincided the interaction of its patients, residents, and those who with regenerative residential projects at the former York 1773 York (the old name for Toronto) comes into existence with the efforts of John Graves Simcoe visit the community. This confluence of social backgrounds, Knitting Mills and Paterson Chocolate Factory, located at Aeneas Shaw builds a log cabin just north of the future Lot Street, just to the west of present-day Trinity 1799 as well as the affordability of the area, has led to an influx 933 and 955 Queen Street West respectively, which have Bellwoods Park, and names his residence “Oakhill” of the creative-class and, as a result, the emergence of been extensively renovated and turned into condominiums. 1800 Asa Danforth oversees construction of Lot Street, which would later be renamed Queen Street its designation as an “Art and Design District.” Following familiar patterns of gentrification, the neighbourhood has Gentrification along West Queen West, which began in the 1802 James Givens purchases Lot 23 on the north side of Queen Street and west of Crawford Street evolved into a destination for fashion, entertainment, and 1980s, has been undertaken by enterprising artists and Construction of a Block House fortification on the north side of Queen Street close to the intersection with 1814 the arts (Whitzman 2009: 186-192; Slater 2004: 312-313). the creative class and managed through municipal policies Bellwoods Avenue designed to promote economic and social revitalization Construction of Gore Vale, the first brick house built in the study area, adjacent to the present Trinity- Housing patterns changed starkly in Parkdale during the (Slater 2004: 304). -

Park Lawn Lake Shore Transportation Master Plan (TMP)

Park Lawn Lake Shore Transportation Master Plan (TMP) This document includes all information that was planned to be presented at the Public Open House originally scheduled to take place on March 24, 2020, that was postponed due to COVID-19. Public Information Update June 2020 Park Lawn / Lake Shore TMP Background & Study Area The Park Lawn Lake Shore Transportation Master Plan (TMP) is the first step in a multi-year process to The Park Lawn Lake Shore TMP Study Area within evaluate options to improve the area's transportation network. Following the TMP launch in 2016, the which potential improvements are being considered is TMP was put on hold until a final decision was reached on the land use of the Christie's Site. bound by: Ellis Avenue to the east, Legion Road to the west, The Queensway to the north, Lake Ontario to the south. The Christie's Planning Study was launched in October 2019 with a goal of creating a comprehensive planning framework for the area. The study will result in a Secondary Plan and Zoning By-law for the site. The traffic analysis for this study spans a broader area, and includes: •Gardiner Expressway, from Kipling Avenue on/off Ramps to Jameson Avenue on/off Ramps •Lake Shore Boulevard, from Legion Road to Meeting Objectives Jameson Avenue •The Queensway, from Royal York Road to Jameson Avenue The Christie’s Planning Study Area sits on the former Mr. Christie factory site, and is bound by the Gardiner Expressway to the north; Lake Shore Boulevard West to the east and southeast; and Park Lawn Road to the west and southwest. -

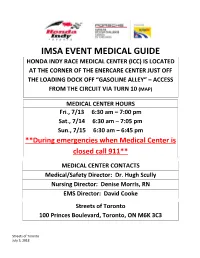

Imsa Event Medical Guide

IMSA EVENT MEDICAL GUIDE HONDA INDY RACE MEDICAL CENTER (ICC) IS LOCATED AT THE CORNER OF THE ENERCARE CENTER JUST OFF THE LOADING DOCK OFF “GASOLINE ALLEY” – ACCESS FROM THE CIRCUIT VIA TURN 10 (MAP) MEDICAL CENTER HOURS Fri., 7/13 6:30 am – 7:00 pm Sat., 7/14 6:30 am – 7:05 pm Sun., 7/15 6:30 am – 6:45 pm **During emergencies when Medical Center is closed call 911** MEDICAL CENTER CONTACTS Medical/Safety Director: Dr. Hugh Scully Nursing Director: Denise Morris, RN EMS Director: David Cooke Streets of Toronto 100 Princes Boulevard, Toronto, ON M6K 3C3 Streets of Toronto July 3, 2018 Hospitals / Directions St. Michael’s Hospital 4.7 km/ 2.9 mi – 19 min 30 Bond Street Toronto, Ontario M5B 1W8 Main: 416-864-6060 ED: 416-864-5094 o Head east on Princes' Blvd toward Canada Blvd o Turn right onto Strachan Ave o Use the left 2 lanes to turn left at the 1st cross street onto Lake Shore Blvd W o Continue straight to stay on Lake Shore Blvd W o Use the middle lane to stay on Lake Shore Blvd W o Continue onto Harbour St o Keep left to stay on Harbour St o Slight left onto Yonge St o Parts of this road may be closed at certain times or days o Turn right onto Shuter St Turn right onto Bond St (Destination will be on the right) o Ross Tilley Burn Center 16.2 km/ 10.1 mi – 28 min at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center 2075 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5 Main: 416-480-6100 Burn Center: 416-480-6814 o Head east on Princes' Blvd toward Canada Blvd o Turn right onto Strachan Ave o Use the left 2 lanes to turn left at the 1st cross street onto Lake Shore Blvd W o Continue straight to stay on Lake Shore Blvd W o Use the right lane to take the Gardiner Expressway E ramp o Merge onto Gardiner Expy E o Use the left 2 lanes to take the Don Valley Parkway exit o Continue onto Don Valley Pkwy N o Take the Bayview Avenue exit toward Bloor Street o Keep right at the fork, follow signs for Bayview Ave N and merge onto Bayview Ave o Turn right onto Wellness Way o Turn right onto Hospital Road (Destination will be on the right) Hospitals / Directions St. -

Demanding the Right to the City and the Right to Housing (R2C/R2H): Best Practices for Supporting Community Organizing

Demanding the Right to the City and the Right to Housing (R2C/R2H): Best Practices for Supporting Community Organizing Martine August & Cole Webber December 2019 Parkdale Community Legal Services ii About This Report The goal of this report was to examine how to promote the Right to the City (R2C) and the Right to Housing (R2H) through strategic legal and organizing activities that mobilize against displacement. This report fulfills the goal to prepare a co-authored research paper and tools for evaluating community organizing. It focuses on relationships between agencies (including legal clinics) and organizers in three cities. Martine August is an Assistant Professor in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo Cole Webber is a Community Legal Worker at Parkdale Community Legal Services Support for the report was provided by Maytree. 2019 | Toronto, Ontario: Parkdale Community Legal Services iii Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................... IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. VI INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 THE RIGHT TO THE CITY AND THE RIGHT TO HOUSING (R2C/R2H) ....................................... 3 The Right to the City................................................................................................................. -

GET TORONTO MOVING Transportation Plan

2 ‘GET TORONTO MOVING’ TRANSPORTATION PLAN SUMMARY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Who we are 4 Policy 4 Rapid Transit Subways 5 Findings of the 1985 ‘Network 2011’ TTC Study 6 Transit Projects Around The World 6 ‘SmartTrack’ 7 GO Trains 7 Roads 10 Elevated Gardiner Expressway 12 Bicycle Trails 14 Funding 16 Toronto Transportation History Timeline 17 BIBLIOGRAPHY ‘Network 2011’ TTC Report 1985 Boro Lukovic – tunnelling expert Globe and Mail newspaper GO Transit Canadian Automobile Association Canada Pension Plan Investment Board Ontario Teachers Pension Fund Investment Board City of Toronto Metrolinx 3 WHO WE ARE The task force who have contributed to this plan consist of: James Alcock – Urban transportation planner Bruce Bryer – Retired TTC employee Kurt Christensen – political advisor and former Scarborough City Councillor Bill Robertson – Civil Engineer Kevin Walters – Civil Engineer POLICY There are two ways needed to end traffic gridlock: High-capacity rapid transit and improved traffic flow. The overall guiding policy of this plan is: the "Get Toronto Moving' Transportation Plan oversees policies and projects with the goal of improving the efficiency of all modes of transportation which are the choices of the people of Toronto, including automobiles, public transit, cycling and walking within available corridors. The City has no place to ‘encourage’ or entice people to switch to different forms of transportation from what they regularly use. That is the free choice of the people. The City and the Province are only responsible for providing the facilities for the transportation choices of the people. Neighbourhoods and residential and commercial communities must be left intact to flourish. -

EVENT NOTICE Sporting Life 10K Road Closures Sunday, May 14, 2017

EVENT NOTICE Sporting Life 10k Road Closures Sunday, May 14, 2017 On May 14th, we invite you to cheer on over 23,000 participants that are out to make a difference in the lives of children affected by childhood cancer in this year’s Sporting Life 10k, as they run and walk down Yonge St. fundraising over $2.2 million for Camp Oochigeas. This is one of Canada’s premier running events with the largest net proceeds going to charity. RUN START TIME - 7:30am Road Closures: Fort York Blvd* will be closed from Bathurst Street to Lakeshore Blvd from 4:30am until 12:30pm. • Local access will be available to Fort York Blvd area condominiums. Yonge Street will be closed from Lawrence Avenue to Eglinton Avenue from 4:30am until 10:30am. Road closures will be in effect from 7:15am – approximately 11:30am. The streets will re-open as soon as the last participant passes through each section and the Toronto Police Department deems it safe to re-open the roads. 1. Yonge Street between Eglinton Avenue and Richmond Street 2. Richmond Street between Yonge Street and Peter Street 3. Peter Street/Blue Jays Way between Richmond Street and Front Street Castlefield)Ave) 4. Westbound Front Street between Blue Jays Way and Bathurst Street (Eastbound traffic will be permitted from Spadina Avenue) Eglinton(Ave( 1k 5. Bathurst Street between Front Street and Lakeshore Boulevard 6. Fleet Street from Strachan Avenue to Fort York Boulevard 2k Yonge(St( 3k Vehicles will be allowed to cross at major intersections when deemed safe by police officers on duty. -

Activeto Next Steps for 2021: Supplementary Report

REPORT FOR ACTION ActiveTO Next Steps for 2021: Supplementary Report Date: April 6, 2021 To: City Council From: General Manager, Transportation Services Wards: Ward(s) affected or All SUMMARY Throughout 2020, the City of Toronto's Transportation Services Division introduced a variety of COVID-19 response programs in consultation with the Medical Officer of Health to accommodate the need for residents to be outside of their homes while physical distancing. These programs, including ActiveTO, transformed Toronto's streets to support the city during the first summer of the pandemic. ActiveTO was composed of three main programs; Major Road Closures, Quiet Streets and Cycling Network Expansion. This set of programs enabled the largest expansion of cycling infrastructure in the City's history and supported thousands of safe cycling and walking trips to essential services and recreation for mental and physical health. On March 23, 2021, Infrastructure and Environment Committee (IEC) endorsed the recommendations of IE 20.12 ActiveTO - Lessons Learned from 2020 and Next Steps for 2021, and requested that (1) the General Manager, Transportation Services report directly to the April 7 and 8, 2021 City Council meeting on the following: a. opportunities to accommodate Lake Shore Boulevard West ActiveTO partial or full closures on select weekends or consider alternate ActiveTO installations, similar to Bayview Avenue; b. opportunities for additional ActiveTO locations, including on the Exhibition Place grounds; and c. opportunities to accelerate traffic-calming in local neighbourhoods through the refocused efforts mentioned in the report, and creating enhanced Quiet Streets, based on lessons learned in 2020, as well as opportunities for a Quiet Neighbourhoods approach where appropriate. -

Housing Services Act, 2011 - O

HOUSING SERVICES ACT, 2011 - O. Reg. 368/11 http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/source/regs/english/2011/elaws_src_r... ONTARIO REGULATION 368/11 made under the HOUSING SERVICES ACT, 2011 Made: June 22, 2011 Filed: August 10, 2011 Published on e-Laws: August 12, 2011 Printed in The Ontario Gazette: August 27, 2011 DESIGNATED HOUSING PROJECTS — SECTION 68 OF THE ACT Designated housing projects 1. (1) For the purposes of subsection 68 (1) of the Act, a housing project set out in an item of a Schedule is designated for the transferred housing program referred to in that item. (2) For the purposes of subsection (1), the housing program referred to in an item is the housing program described in Schedule 1 to Ontario Regulation 367/11 (General) made under the Act for the program category number set out in the item. Commencement 2. This Regulation comes into force on the later of the day section 184 of Schedule 1 (Housing Services Act, 2011) to the Strong Communities through Affordable Housing Act, 2011 comes into force and the day this Regulation is filed. SCHEDULE 1 CITY OF BRANTFORD Item Program Housing Project 1. 1 (a) 17 Marie Ave. / 46-52 (Even) Pontiac Street / 43, 45 Tecumseh Street, Brantford — Riverside Gardens 2. 1 (a) 676 Grey St., Brantford — Grey Street 3. 1 (a) 5 Fordview Court, Brantford — Gilkison Street 4. 1 (a) 359 Darling St., Brantford — Darling Street 5. 1 (a) 332 North Park St. / 50 Hayhurst Rd. / 56, 68 Memorial Dr., Brantford — Memorial Drive 6. 1 (a) 40-50 (Even) Willow St., Paris — Willow Street 7. -

Jameson Avenue

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Amendments to Parking and Stopping Regulations – Jameson Avenue Date: August 25, 2009 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Transportation Services Toronto and East York Wards: Parkdale-High Park, Ward 14 Report Ts09144te.top.doc Number: SUMMARY This staff report is about a matter for which Community Council has delegated authority from City Council to make a final decision. Transportation Services is requesting authority to rescind the “No Parking” (morning) and “No Stopping” (afternoon) rush hour restrictions on the east side of Jameson Avenue, between Queen Street West and Springhurst Avenue. This will increase parking opportunities for local residents and visitors during the daytime, and resolve existing contradictory regulations in the traffic by-law. RECOMMENDATIONS Transportation Services recommends that Toronto and East York Community Council: 1. Rescind the “No Parking, from 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m., except Saturday, Sunday, and Public Holidays” regulation on east side of Jameson Avenue for the entire length. 2. Rescind the “No Parking, from 7:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., Monday to Friday” regulation on the east side of Jameson Avenue, between a point 36 metres south of King Street West and a point 91 metres further south. 3. Rescind the “No Parking Anytime” regulation on the east side of Jameson Avenue, between Queen Street West and a point 36.6 metres south. Parking Amendments-Jameson Avenue 1 4. Rescind the “No Stopping, from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., except Saturday, Sunday, and Public Holidays” regulation on the east side of Jameson Avenue for the entire length. -

Staff Report

STAFF REPORT January 3, 2003 To: Toronto East York Community Council From: Joe Halstead, Commissioner Economic Development, Culture and Tourism Subject: Central Waterfront (Port Lands Industrial Area) – Inclusion on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties Toronto-Danforth - Ward 30 Purpose: This report recommends the inclusion on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties of five properties in the Port Lands Industrial Area of the Central Waterfront. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: There are no financial implications resulting from the adoption of this report. Recommendations: (1) City Council include on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties the following five properties located in the Port Lands Industrial Area of the Central Waterfront: (i) Cherry Beach Life Saving Station and Change Room (ii) 275 Cherry Street (Dominion Bank Building) (iii) 309 Cherry Street (William McGill and Company Building) (iv) 39 Commissioners Street (Fire Hall No. 30) (v) 400 Commissioners Street (City of Toronto Incinerator); and (2) the appropriate City Officials be authorized and directed to take the necessary action to give effect thereto. Background: The Toronto Preservation Board at its meeting held on November 26, 2002 endorsed the recommendations as noted above. At the request of the property owners, the Toronto - 2 - Preservation Board deferred consideration of 13 additional properties in the Central Waterfront area for inclusion on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties. Culture Division staff plan to meet with the owners of the 13 properties prior to reporting back to the Toronto Preservation Board. In June 2002, City Planning, Urban Development Services requested that Culture Division staff take part in a planning study currently underway within the boundaries of the Central Waterfront area. -

Pedestrian Safety Review – Spadina Avenue

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Pedestrian Safety Review – Spadina Avenue Date: October 13, 2015 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Transportation Services, Toronto and East York District Wards: Trinity-Spadina, Ward 20 Reference Ts2015203te.top.doc Number: SUMMARY As the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) operates a transit service on Spadina Avenue, City Council approval of this report is required. At the June 16, 2015 meeting of the Toronto and East York Community Council, Transportation Services was directed to undertake a pedestrian safety review on Spadina Avenue, between Lake Shore Boulevard West and the Metrolinx rail corridor, and advise on the feasibility of installing a pedestrian crossing on the south side of the Bremner Boulevard/Fort York Boulevard intersection, as well as any other safety measures. Transportation Services does not support the installation of a pedestrian crossing on the south side of the Spadina Avenue and Bremner Boulevard/Fort York Boulevard intersection, based on the negative impacts on the intersection capacity that will result. The City of Toronto's policy requires that pedestrian crossings not be permitted where they will conflict with dual turn lanes at an intersection. RECOMMENDATIONS Transportation Services, Toronto and East York District recommends that: 1. City Council deny the introduction of a pedestrian crossing on the south side of Spadina Avenue at the intersection with Bremner Boulevard/Fort York Boulevard. Pedestrian Safety Review – Spadina Ave. 1 Financial Impact There are no financial implications to the report. DECISION HISTORY On June 16, 2015, Toronto and East York Community Council requested Transportation Services staff undertake a traffic study on Spadina Avenue, between Lake Shore Boulevard West and the Metrolinx rail corridor (Item TE7.120). -

Exhibition Place

EXHIBITION PLACE TFC TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Immediate and Intermediate Recommendations MAY 2019 FINAL 100 Commerce Valley Drive West T: +1 905 882-1100 Thornhill, ON F: +1 905 882-0055 Canada L3T 0A1 wsp.com TFC TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT PLAN IMMEDIATE AND INTERMEDIATE RECOMMENDATIONS EXHIBITION PLACE FINAL PROJECT NO.: 191-03512 DATE: MAY 2019 WSP 100 COMMERCE VALLEY DRIVE WEST THORNHILL, ON CANADA L3T 0A1 T: +1 905 882-1100 F: +1 905 882-0055 WSP.COM May 21, 2019 Exhibition Place Enercare Centre / Beanfield Centre 100 Princes' Blvd. Suite 1 Exhibition Place Toronto, ON M6K 3C3 Attention: Mr. Tony Porter, Director, Parking & Security Services Subject: TFC Transportation Management Plan, Immediate and Intermediate Recommendations, Exhibition Place Dear Mr. Porter WSP Canada Inc. is pleased to submit the TFC Transportation Management Plan to address immediate and intermediate recommendations for Exhibition Place. The potential immediate solutions are those that could be completed by Exhibition Place without the involvement of other stakeholders and can be completed within 12 months. The intermediate solutions are those that would require Exhibition Place to work with one or more external stakeholder(s) and would typically take beyond 12 months to complete. The traffic management recommendations for immediate and intermediate implementation include: A. Potential Immediate Solutions within Exhibition Place: • Modification and adjustments to key traffic signals on the Exhibition grounds using Paid Duty Officers; • Remove pavement grooves