DECODING AMERICAN CULTURES in the Global Context R IA S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

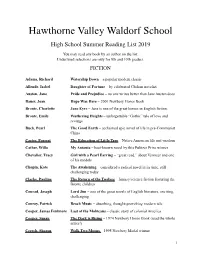

Summer Reading List.Pages

Hawthorne Valley Waldorf School High School Summer Reading List 2019 You may read any book by an author on the list. Underlined selections are only for 9th and 10th graders. FICTION Adams, Richard Watership Down – a popular modern classic Allende, Isabel Daughter of Fortune – by celebrated Chilean novelist Austen, Jane Pride and Prejudice – no one writes better than Jane Austen does Bauer, Joan Hope Was Here – 2001 Newbery Honor Book Bronte, Charlotte Jane Eyre – Jane is one of the great heroes in English fiction. Bronte, Emily Wuthering Heights – unforgettable “Gothic” tale of love and revenge Buck, Pearl The Good Earth – acclaimed epic novel of life in pre-Communist China Carter, Forrest The Education of Little Tree – Native American life and wisdom Cather, Willa My Antonia – best-known novel by this Pulitzer Prize winner Chevalier, Tracy Girl with a Pearl Earring – “great read,” about Vermeer and one of his models Chopin, Kate The Awakening – considered a radical novel in its time, still challenging today Clarke, Pauline The Return of the Twelves – fantasy/science fiction featuring the Bronte children Conrad, Joseph Lord Jim – one of the great novels of English literature, exciting, challenging Conroy, Patrick Beach Music – absorbing, thought-provoking modern tale Cooper, James Fenimore Last of the Mohicans – classic story of colonial America Cooper, Susan The Dark is Rising – 1974 Newbery Honor Book (read the whole series!) Creech, Sharon Walk Two Moons – 1995 Newbery Medal winner !1 Cushman, Karen Catherine, Called Birdy – 1995 Newbery -

11Th Grade Recommended Readings

11th Grade Recommended Readings A Bell for Adano - John Hersey Sister Carrie - Theodore Dreiser A Lesson Before Dying - Ernest J. Gaines Slaughterhouse Five - Kurt Vonnegut A Raisin in the Sun - Lorraine Hansberry Sophie's Choice - William Styron A Yellow Raft in Blue Water - Michael Dorris Stranger in a Strange Land - Robert Heinlein An American Tragedy - Theodore Dreiser Streetcar Named Desire - Tennessee Williams And the Earth Did Not Devour Him - Tomas Rivera Studs Lonigan - James Farrell Babbitt - Sinclair Lewis The Andromeda Strain - Michael Crichton Black Boy - Richard Wright The Assistant - Bernard Malamud Catch 22 - Joseph Heller The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plath Daisy Miller - Henry James The Bridge of San Luis Rey - Thornton Wilder Death of a Salesman - Arthur Miller The Crucible - Arthur Miller East of Eden - John Steinbeck The Grapes of Wrath - John Steinbeck Ethan Frome - Edith Wharton The Great Gatsby - F. Scott Fitzgerald Fallen Angels - William Dean Myers The Great Santini - Pat Conroy Family - J. California Cooper The Invisible Man - Ralph Ellison First Confession - Montserrat Fontes The Jungle - Upton Sinclair For Whom the Bell Tolls - Ernest Hemingway The Kitchen God's Wife - Amy Tan Friendly Persuasion - Jessamyn West The Last Picture Show - Larry McMurtry Hotel New Hampshire - John Irving The Magician of Lublin - Isaac Singer Hunger of Memory - Richard Rodriguez The Maltese Falcon - Dashiell Hammett In Cold Blood - Truman Capote The Massacre at Fall Creek - Jessamyn West J.B. - Archibald McLeish The Mysterious Stranger -

Honors American Literature Summer Reading List 2021-2022

Honors American Literature Reading List 2020-2021 Required Readings: James, Henry Washington Square Glaspell, Susan Trifles Suggested Readings: Cooper, James Fenimore Last of the Mohicans Hawthorne, Nathaniel The Scarlet Letter James, Henry Portrait of a Lady Faulkner, William Light in August The Sound and the Fury Hemingway, Ernest For Whom the Bell Tolls A Farewell to Arms Lewis, Sinclair Babbitt Main Street Cather, Willa My Antonia John Steinbeck The Grapes of Wrath McCullers, Carson A Member of the Wedding The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter Wharton, Edith Ethan Frome Arnow, Hariette The Dollmaker Melville, Herman Moby Dick London, Jack White Fang Richter, Conrad The Trees The Fields The Town Herbert, Frank Dune Warren, Robert Penn All the King’s Men Kantor, McKinley Andersonville Agee, James A Death in the Family Fitzgerald, F. Scott Tender Is the Night Tan, Amy The Joy Luck Club Hersey, John A Bell for Adano Michener, James Hawaii Lee, Harper To Kill a Mockingbird The essay and the test for the two required readings are the assignments for the first day of school. There are no acceptable excuses for late work. Manage your time and do not wait until the last minute. I do not want to hear that your printer would not work or that your printer ran out of ink or that you do not have a computer and, therefore, had to wait for your best friend to finish his/her report before you could type yours. The essay and any succeeding reports during the year are to be typed in Times New Roman 12. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R. -

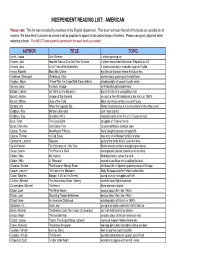

Independent Reading List: American

INDEPENDENT READING LIST: AMERICAN Please note: This list was compiled by members of the English department. That does not mean that all of the books are suitable for all readers. We have tried to provide as varied a list as possible to appeal to the widest range of readers. Please use good judgment when selecting a book. You MUST have parental permission for each book you select. AUTHOR TITLE TOPIC Alcott, Louisa Little Women 4 sisters growing up Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Got Their Accents 4 sisters move from Dominican Republic to U.S. Alvarez, Julia In the Time of the Butterflies 4 sisters involved in revolution against Trujillo Anaya, Rudolfo Bless Me, Ultima boy tries to discover where his future lies Anderson, Sherwood Winesburg, Ohio stories about growing up in small town Angelou, Maya I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (others) autobiography of woman's early years Asimov, Isaac Fantastic Voyage sci-fi trip through bloodstream Baldwin, James Go Tell It on the Mountain day in the life of a young Black man Barrett, Andrea Voyage of the Narwhal sailing trip from Philadelphia to the Arctic in 1850's Barrett, William Lilies of the Field Black man helps white nuns roof house Borland, Hal When the Legends Die Native American boy & his encounters w/ the white world Bradbury, Ray Martian Chronicles sci-fi short stories Bradbury, Ray Dandelion Wine magical events in the life of a 12-year-old boy Buck, Pearl The Good Earth struggles of Chinese family Burns, Olive Ann Cold Sassy Tree 12-year-old boy in Georgia town Capote, Truman Breakfast -

Summer Reading 2016

Summer Reading 2016 Students Entering Grades Six through Eight The Upper School Summer Reading Assignment is attached below. Each grade is given five optional novels, from which two must be chosen. In addition to the two required books, we are also asking each student to read an additional three books from either his/her grade list, the Additional Reading List below, or other books that may interest him or her and are of equal literary merit. Your local libraries are sure to have other books in genres you may also enjoy. Required Reading for Upper School Choose at least TWO books from the five options. th Entering 6 Grade: Hatchet, Gary Paulsen The Golden Compass, Philip Pullman The Alchemist, Paulo Coelho White Fang, Jack London The Book Thief, Markus Zusak th Entering 7 Grade: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, C.S. Lewis A Separate Peace, John Knowles The Three Musketeers, Alexandre Dumas th Entering 8 Grade: Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson The Hound of the Baskervilles, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle 1984, George Orwell Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen Recommended List of Additional Reading for Grades Six through Eight Across Five Aprils, Irene Hunt Artemis Fowl, Eoin Colfer Becoming Naomi Leon, Pam Munoz Ryan Broken Bridge, Lynne Reid Banks Chasing Vermeer, Blue Balliett Crispin: The Cross of Lead, AVI Far North, Will Hobbs Flipped, Wendelin Van Draanen Habibi, Naomi Shihab Nye Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, J.K. Rowling I Am the Cheese, Robert Cormier House of the Scorpion, Nancy Farmer Let the Circle Be Unbroken, Mildred Taylor The Moorchild, Eloise McGraw New Found Land: Lewis and Clark’s Voyage of Discovery, Allan Wolf Pictures of Hollis Woods, Patricia Reilly Giff The Road from Coorain, Jill Ker Conway The Thief Lord, Cornelia Caroline Funke A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Betty Smith Walk Two Moons, Sharon Creech Watership Down, Richard Adams Silent to the Bone, E.L. -

Sociological Novels Reviewed in Sociology and Social Research, 1925-1958 Michael R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2006 Sociological Novels Reviewed in Sociology and Social Research, 1925-1958 Michael R. Hill University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Sociological Novels Reviewed in Sociology and Social Research, 1925-1958" (2006). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 355. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/355 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R. 2006. “Sociological Novels Reviewed in Sociology and Social Research, 1925-1958.” Sociological Origins 5 (Fall): 54-59. Sociological Novels Reviewed in Sociology and Social Research, 1925-1958 1 Michael R. Hill HE BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORD reveals the novel as a distinctive and frequently used format for sociological inquiry and exposition.2 From 1925 to 1958, the pages of Sociology and Social Research identified and reviewed 140 examples of sociological T 3 novels. A bibliography of these novels is provided here, annotated with citations for the reviews in Sociology and Social Research. This “library” of sociological novels is a useful resource for research on American culture, student projects, and (not unimportantly) recreational reading that combines business with pleasure. Under the editorship of Emory S. Bogardus, Sociology and Social Research routinely opened its pages to reviews of alternative forms of sociological expression. -

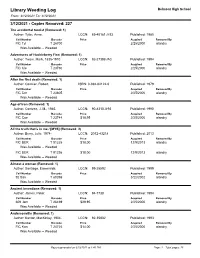

Library Weeding Log Belmont High School From: 3/12/2021 To: 3/12/2021

Library Weeding Log Belmont High School From: 3/12/2021 To: 3/12/2021 3/12/2021 - Copies Removed: 227 The accidental tourist (Removed: 1) Author: Tyler, Anne. LCCN: 85-40161 //r93 Published: 1985 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC Tyl T 26700 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Removed: 1) Author: Twain, Mark, 1835-1910. LCCN: 92-27398 /AC Published: 1994 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC Cle T 23730 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded After the first death (Removed: 1) Author: Cormier, Robert. ISBN: 0-394-84122-0 Published: 1979 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC Cor T 23805 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Age of Iron (Removed: 1) Author: Coetzee, J. M., 1940- LCCN: 90-8310 //r93 Published: 1990 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC Coe T 23744 $18.95 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded All the truth that's in me / [MYS] (Removed: 2) Author: Berry, Julie, 1974- LCCN: 2012-43218 Published: 2013 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC BER T 91225 $18.00 12/9/2013 alandry Was Available -- Weeded FIC BER T 91226 $18.00 12/9/2013 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Almost a woman (Removed: 1) Author: Santiago, Esmeralda. LCCN: 99-25592 Published: 1999 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 92 San T 60398 3/22/2002 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Ancient inventions (Removed: 1) Author: James, Peter. LCCN: 94-7738 Published: 1994 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 609 Jam T 26439 $29.95 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Andersonville (Removed: 1) Author: Kantor, MacKinlay, 1904- LCCN: 92-35802 Published: 1993 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC Kan T 24725 $14.00 2/25/2000 alandry Was Available -- Weeded Report generated on 3/23/2021 at 1:40 PM Page: 1 Total pages: 26 Library Weeding Log Belmont High School From: 3/12/2021 To: 3/12/2021 3/12/2021 - Copies Removed: 227 Animal, vegetable, miracle : a year of food life (Removed: 3) Author: Kingsolver, Barbara. -

Reading List: Carson City High School

Reading List: Carson City High School Author Title Description Notes Samplings of American Literature *Agee, James A Death in the Story of loss and heartbreak felt when a young father dies. Family Anaya, Bless Me Ultima Anya espresses his Mexican-American heritage by Rudolpho combining traditional folklore, Spanish storytelling and ancient Mexican mythology. This novel, for which Anaya won a literary award for the best in Chicano novels, concerns a young boy growing up in New Mexico in the late 1940’s. *Baldwin, James Go Tell It On the Semi-autobiographical novel about a 14-year-old black Mountain youth's religious conversion. *Bellamy, Looking Written in 1887 about a young man who travels in time to a Edward Backward: 2000- utopian year 2000, where economic security and a healthy 1887 moral environment have reduced crime. *Bellow, Saul Seize the Day A son grapples with his love and hate for an unworthy father. *Bradbury, Ray Fahrenheit 451 Reading is a crime, and firemen burn books in this futuristic society. Buck, Pearl The Good Earth Nobel-prize winner Buck’s novel focuses upon the rise of Wang Lung, a Chinese peasant, from poverty to the life of a Rick landowner. O-lan, his patient wife, aids his success. Burns, Olive Cold Sassy Tree Set in a turn-of-the-century Georgia town, Cold Sassy Tree Ann details the coming of age of Will Tweedy as he adjusts to his grandfather’s hasty marriage to a much younger woman. Cather, Willa My Antonia Cather’s novel portrays the life of Bohemian immigrant and American setters in the Nebraska frontier. -

A Social Studies Class by Selecting Television Shows, Novels: Films, and Plays Which Broaden the Students' Environment Beyond Their Personal Experience

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 679 TE 000 898 By- Butman, Alexander M. A Novel Approach to Social Studies. Pub Date Jan 67 Note- 4p. Journal Cit- The Teachers Guide to Media & Methods; v3 n5 p30-1,48 Jan 1967 EDRS Price MF-SO.25 NC-S0.30 Descriptors-*American History, *Mass Media, *Novels, Secondary Education, *Social Studies Teachers can help students to understand, retain, and relate to what is taught in a Social Studies class by selecting television shows, novels: films, and plays which broaden the students' environment beyond their personal experience. Several events in American History can be made more stimulating by the use of novels to present vivid pictures of happenings. For example, "Last of the Mohicans" and "Northwest Passage" can help students to experience scenes of exploration and early settlement; and "Gone With the Wind" and "The Red Badge of Courage" present accounts of the Civil War. (A selected list of novels for use in Social Studies classes, and criteria for the selection and use of fiction are provided.) (SW) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE Of EDUCkTION POSITION OR POLICY. THE TEACHERS me GUIDE TO &methods An Expansion of SCHOOLPAPERBACK JOURNAL January, 1967 Vol. 3, No. 5 ADVISORY BOARD Max Bogart Asst. Dir., Div. of Curriculum & Instruc. EDITORIALS State Dept. of Educ., Trenton, N. J. IN THE MIDDLE 5 Charlotte Brooks Frank McLaughlin Supervising Dir.