Te Awarua-O-Porirua Whaitua Committee, See Te Awarua-O-Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme, Available from the Greater Wellington Website

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 Environment Management Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 J. R. Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington GW/EMI-G-10/164 PO Box 11646 December 2010 T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council and as such does not constitute Council’s policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Council does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Council endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Council requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. The report may be cited as: Milne, J. 2010. Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10. -

Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council November 2013 Cover Photo: Onepoto Arm, Porirua Harbour, January 2013. Te Onepoto Bay showing the constructed causeway restricting tidal flows. Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council by Leigh Stevens and Barry Robertson Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7001, Ph 021 417 936 0275 417 935, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii All photos by Wriggle except where noted otherwise. Contents Porirua Harbour - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 5 3. Results and Discussion . 10 Intertidal Substrate Mapping . 10 Changes in Intertidal Estuary Soft Mud 2008-2013. 13 Intertidal Macroalgal Cover. 14 Changes in Intertidal Macroalgal Cover 2008 - 2013 . 16 Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Changes in Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Saltmarsh Mapping . 21 Changes in Saltmarsh Cover 2008-2013 . 24 Terrestrial Margin Cover . 25 4. Summary and Conclusions . 27 5. Monitoring ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 6. Management . 28 7. Acknowledgements . 29 8. References . 29 Appendix 1. Broad Scale Habitat Classification Definitions. 32 List of Figures Figure 1. Likely extent of historical estuary and saltmarsh habitat in relation to Porirua Harbour today. 2 Figure 2. Porirua Harbour showing fine scale sites and sediment plates estab. in 2007/8, 2012, and 2013. 4 Figure 3. Visual rating scale for percentage cover estimates of macroalgae (top) and seagrass (bottom). 5 Figure 4. Map of Intertidal Substrate Types - Porirua Harbour, Jan. 2013. 11 Figure 5. Change in the percentage of mud and sand substrate in Porirua Harbour, 2008-2013. 13 Figure 6. -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

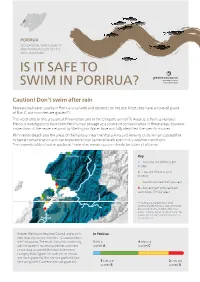

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site. -

Te Awarua-O- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme

Te Awarua-o- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee, April 2019 Front cover: Image of Porirua Harbour looking south Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua process is the collaborative discussion on the future of our streams and rivers, the water that connects us, the land and our communities, and how we manage and protect our natural resources. Stu Farrant Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Foreword from Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Like most areas of New Zealand, the communities within the Te Awarua-o-Porirua catchment have been defined by their intimate relationship with water. Early Māori established kāinga (villages) to utilise transformation of the catchment has been a steady the abundant mahinga kai (food harvested from decline in the quality of fresh and coastal waters and the streams, estuary and land) and other resources, the health of ecosystems. Contaminants are flushed travel routes and to seek protection from invaders. from urban and rural land and aging infrastructure Early European development rapidly spread struggles to serve the demands of a growing along the catchment’s streams and relied on the population, with overflows of wastewater a common reclamation of tidal margins for rail and road links occurrence during large rainfall events. These water and the development of what later became Porirua’s quality issues, coupled with extensive infilling and town centre and Elsdon. As the population grew, reclamation, have resulted in the severance of infrastructure was developed to drain stormwater and communities from the once abundant waterways and wastewater and protect the growing communities food and other resources they provided. -

Porirua – Our Place, Our Future, Our Challenge Let's Kōrero

COPYRIGHT © You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to Porirua City Council. Published March 2021. Porirua City Council 16 Cobham Court PO Box 50218 Porirua 5240 This document is available on our website poriruacity.govt.nz Porirua – our place, our future, our challenge Let’s kōrero Consultation Document for the proposed Long-term Plan 2021-51 Message from Ngāti Toa Rangatira E te iwi e noho nei i te riu o Porirua, tēnā koutou katoa The development of the city's Long-term Plan 2021-2051 will bring changes to our city that we will be proud of. Between now and 2051 we will see Porirua transform into a vibrant and exciting place to be for residents and people who choose to work here. We are blessed with hills, waterways, Te Mana o Kupe bushwalks and two magnificent harbours, Porirua and Pāuatahanui, as well as rich histories all anchored by Te Matahourua, the anchor left here by Kupe. As a challenge to all of us – we must look after our environment and look after each other, especially our tamariki and rangatahi. Nou te rourou, naku te rourou ka ora ai te Iwi With your contribution, and my contribution the people will thrive Taku Parai Chairman, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira 2 Consultation Document for the proposed LTP 2021-51 Contents Mai i tō Koutou Koromatua 4 From your Mayor Executive summary 8 Rates 10 The challenges for our city 11 Your views 16 Investment in the 3 waters – drinking water, wastewater 17 & stormwater 1. -

Distribution of Geological Materials in Lower Hutt and Porirua, New Zealand a Component of a Ground Shaking Hazard Assessment

332 DISTRIBUTION OF GEOLOGICAL MATERIALS IN LOWER HUTT AND PORIRUA, NEW ZEALAND A COMPONENT OF A GROUND SHAKING HAZARD ASSESSMENT G. D. Dellow1 , S. A. L. Read 1 , J. G. Begg1 , R. J. Van Dissen1 , N. D. Perrin1 ABSTRACT Geological materials in the Lower Hutt, Eastbourne, Wainuiomata, and Porirua urban areas are mapped and described as part of a multi-disciplinary assessment of seismic ground shaking hazards. Emphasis is mainly on the flat-lying parts of these areas which are underlain by variable Quaternary-age sediments that overlie Permian-Mesowic age 'greywacke' bedrock. Within the Quaternary-age sediments, the two material types recognised on strength characteristics are: 1) Soft sediments, typically composed of normally consolidated, fine-grained materials (sand, silt and clay), with typical standard penetration values (SPT) of <20 blows/300 mm; and 2) Loose to compact coarser-grained materials (sand, gravel), with SPT values of > 20 blows/ 300 mm. The total thickness and nature of Quaternary-age sediments in the study areas is described, with particular emphasis on the thickness and geotechnical properties of near-surface sediments. Such sediments are considered likely to have a significant influence on the an1plification and attenuation of ground shaking intensity during earthquakes. In the Lower Hutt valley, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of -16 kni. Such soft sediments underlie much of Petone and the Lower Hutt urban and city centres, and have a maximum known thickness of 27 m near the western end of the Petone foreshore. In the Wainuiomata area, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of - 3 krn2, and attain a maximum thickness of 32 m. -

Te Awarua-O- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme

Te Awarua-o- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee, April 2019 Front cover: Image of Porirua Harbour looking south Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua process is the collaborative discussion on the future of our streams and rivers, the water that connects us, the land and our communities, and how we manage and protect our natural resources. Stu Farrant Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Foreword from Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Like most areas of New Zealand, the communities within the Te Awarua-o-Porirua catchment have been defined by their intimate relationship with water. Early Māori established kāinga (villages) to utilise transformation of the catchment has been a steady the abundant mahinga kai (food harvested from decline in the quality of fresh and coastal waters and the streams, estuary and land) and other resources, the health of ecosystems. Contaminants are flushed travel routes and to seek protection from invaders. from urban and rural land and aging infrastructure Early European development rapidly spread struggles to serve the demands of a growing along the catchment’s streams and relied on the population, with overflows of wastewater a common reclamation of tidal margins for rail and road links occurrence during large rainfall events. These water and the development of what later became Porirua’s quality issues, coupled with extensive infilling and town centre and Elsdon. As the population grew, reclamation, have resulted in the severance of infrastructure was developed to drain stormwater and communities from the once abundant waterways and wastewater and protect the growing communities food and other resources they provided. -

Porirua City Council & Wellington City Council

Attachment 2 THE PORIRUAHARBOURAND ITS CATCHMENT: LITERATURE REVIEW - Appendix 2 AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Reportfor Porirua City Council & Wellington City Council Paul Blaschke Josephine Woods Frances Forsyth Blaschke and Rutherford Environmental Consultants February 2010 LSBN 978-I-877548-26-0 (print) IsBN 978-I-877548-27-7 (online) . Literature review of Porirua Harbour and catchment Appendix 2: Annotated Bibliography Literature Review - Appendix 2 Annotated bibliography of research on Porirua Harbour and catchment Table of contents Introduction. ................................. 2 Key references covering a range of topics ..................................................... Geology, geography and soils ........................ Terrestrial biodiversity and catchment land use ............................................... 9 Stream geomorphology and hydrology, including flood assessment ........................... I I Annual water quality survey reports .......................... Stream ecology, water and sediment pollution ............................................................. 19 Beach erosion and coastal change. .................................. Estuarine biota ....................... .......... 23 BSIuarine water quality ....... ................ 28 Harbour sediment contamination. ....... 33 Estuary hydrodynamics and sedimentation .................................................................. 38 Planning, roading, development and environmental assessment of effects. ... 40 Environmental management and restoration plans. -

Connect Water Porirua Network Improvement Programme

Wellington Water Consultancy Panel Connect Water Porirua Network Improvement Programme Wastewater Overflow Reduction Master Plan Strategy November 2019 Wellington Water Consultancy Panel Porirua Network Improvement Programme Wastewater Overflow Reduction Master Plan Strategy November 2019 Document Control/QA Reference: 6511521/1902 Current Status: Final Version Date Prepared By Reviewed By Approved By A 1/11/2019 Abby Jensen Malcolm Franklin Malcolm Franklin B 25/11/2019 Abby Jensen Malcolm Franklin Malcolm Franklin Issuing Office CH2M Beca Ltd Telephone: +64 4 473 7551 L6, Aorangi House Facsimile: 0800 578 967 85 Molesworth Street, Thorndon, Wellington 6011 PO Box 3942, Wellington 6140 New Zealand This report has been prepared by Connect Water, on behalf of Opus International Consultants Ltd, and on the specific instructions of Wellington Water. It is solely for the use of Wellington Water, for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Any use or reliance by any person contrary to the above, to which Connect Water has not given its prior written consent, is at that person’s own risk. Where applicable, in producing this deliverable CH2M Beca does so solely as Subconsultant to Opus International Consultants Ltd and does not assume or accept any liability to Wellington Water. Connect Water (Opus & CH2M Beca) c/- CH2M Beca Ltd Porirua Network Improvement Programme November 2019 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

Mooring Areas Porirua Harbour - Channel

Planning Map 3A Mooring Areas Porirua Harbour - Channel N Titahi Bay 2. Northwest Reservoir Mooring Area Boundaries Legend The extent of the mooring area is defined Mooring area by shading and bounded by the following sight lines: Map grids (NZMG) Onepoto Mooring Area 6009 000 N Western Boundary Papakowhai 0 250 500 1. A bearing of 164 degrees from Onepoto Park Titahi Bay Boating Club Metres (Grid reference: 650 087) extending to 250 metres offshore 1. Titahi Bay Boating Club Eastern Boundary 2. A bearing of 164 degrees from the Northwest Reservoir Onepoto Mooring Area (Grid reference: 654 095) extending 250 metres offshore Grid references from NZMS 260 R26 & Pt R25 Paraparaumu Seaward Boundary 3. 250 m Offshore NZMS 260 R27 Wellington 3. A line 250 metres offshore parallel to the shoreline Base Map: Porirua Harbour New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Chart - Miscellaneous Series No.49 6008 000 N Locality Map 6007 000 N 65 E 66 E 67 E 26 000 26 000 26 000 Planning Map 3B Mooring Areas Porirua Harbour - Inlet Mooring Area Boundaries N The extent of the mooring area is defined by 60 000 N shading and bounded by the following sight lines: Entrance Channel North Side Mooring Area Southern Boundary 1. A point 35 metres from the North Abutment of Legend the Rail Bridge (Grid reference: 669 098) 2. Middle Beacon on the western shore 3. Outer Starboard Marker ana Mooring area (Grid reference: 664 099) Map grids (NZMG) Channel Boundary 3. Along a 168 degree bearing from the Outer Star- board Channel Marker (Grid reference: 665 107) 4. -

Hydrodynamic Inundation Modelling and Delineation of Tsunami Evacuation Zones for Porirua and Kapiti Coast

Hydrodynamic Inundation Modelling and Delineation of Tsunami Evacuation Zones for Porirua and Kapiti Coast C. Mueller W.L. Power X. Wang B. Lukovic GNS Science Consultancy Report 2017/200 August 2017 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of, or reliance on any contents of this Report by any person other than the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council and shall not be liable to any person other than the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: October 2017 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Mueller C, Power WL, Wang X, Lukovic, B. 2017. Hydrodynamic inundation modelling and delineation of tsunami evacuation zones for Porirua and Kapiti Coast. Lower Hutt (NZ): GNS Science. 37 p. (GNS Science consultancy report; 2017/200). Project Number 410W1460-00 Confidential 2017 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................III 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 1.1