Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish with a Mission by Geoff Pryor

Parish with a Mission By Geoff Pryor Foreword - The Parish Today The train escaping Wellington darts first into one tunnel and then into another long, dark tunnel. Leaving behind the bustle of the city, it bursts into a verdant valley and slithers alongside a steep banked but quiet stream all the way to Porirua. It hurtles through the Tawa and Porirua parishes before pulling into Paremata to empty its passengers on the southern outskirts of the Plimmerton parish. The train crosses the bridge at Paremata with Pauatahanui in the background. There is no sign that the train has arrived anywhere particularly significant. There is no outstanding example of engineering feat or architecture, no harbour for ocean going ships or airport. No university campus holds its youth in place. No football stadium echoes to the roar of the crowd. The whaling days have gone and the totara is all felled. Perhaps once Plimmerton was envisaged as the port for the Wellington region, and at one time there was a proposal to build a coal fired generator on the point of the headland. Nothing came of these ideas. All that passed us by and what we are left with is largely what nature intended. Beaches, rocky outcrops, cliffs, rolling hills and wooded valleys, magnificent sunsets and misted coastline. Inland, just beyond Pauatahanui, the little church of St. Joseph, like a broody white hen nestles on its hill top. Just north of Plimmerton, St. Theresa's church hides behind its hedge from the urgency of the main road north. The present day parish stretches in an L shape starting at Pukerua Bay through to Pauatahanui. -

Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council November 2013 Cover Photo: Onepoto Arm, Porirua Harbour, January 2013. Te Onepoto Bay showing the constructed causeway restricting tidal flows. Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council by Leigh Stevens and Barry Robertson Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7001, Ph 021 417 936 0275 417 935, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii All photos by Wriggle except where noted otherwise. Contents Porirua Harbour - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 5 3. Results and Discussion . 10 Intertidal Substrate Mapping . 10 Changes in Intertidal Estuary Soft Mud 2008-2013. 13 Intertidal Macroalgal Cover. 14 Changes in Intertidal Macroalgal Cover 2008 - 2013 . 16 Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Changes in Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Saltmarsh Mapping . 21 Changes in Saltmarsh Cover 2008-2013 . 24 Terrestrial Margin Cover . 25 4. Summary and Conclusions . 27 5. Monitoring ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 6. Management . 28 7. Acknowledgements . 29 8. References . 29 Appendix 1. Broad Scale Habitat Classification Definitions. 32 List of Figures Figure 1. Likely extent of historical estuary and saltmarsh habitat in relation to Porirua Harbour today. 2 Figure 2. Porirua Harbour showing fine scale sites and sediment plates estab. in 2007/8, 2012, and 2013. 4 Figure 3. Visual rating scale for percentage cover estimates of macroalgae (top) and seagrass (bottom). 5 Figure 4. Map of Intertidal Substrate Types - Porirua Harbour, Jan. 2013. 11 Figure 5. Change in the percentage of mud and sand substrate in Porirua Harbour, 2008-2013. 13 Figure 6. -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

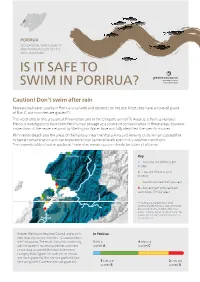

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site. -

Porirua City Walking and Cycling Tracks Brochure

Porirua Pathfinder Looking for a flat pathway that is near a cafe? TRACK 5 and Walking A path suitable for a dog and a wheelchair? A challenging or easy cycle track? When using our pathways remember to > Protect plants & wildlife Cycling Tracks Use our Porirua Pathfinder to find your ideal path. > Remove rubbish > Keep to the track in Porirua City TRACK 38 Go to “www.poriruapathfinder.co.nz” > Consider other people > Clean up after your dog Explore CODE OF CONDUCT FOR SHARED PATHWAYS Shared paths are used by cyclists, walkers, joggers and pushchairs. To help everyone enjoy themselves please Porirua City follow the Code of Conduct for shared pathways. With its beautiful coastline, bush clad hills and parks, Porirua City offers a wealth of wonderful walks and 1. Keep Left: As far as practical, except when passing an- other user going your direction (pass on the right). Go cycle tracks. Whether you’re a fitness enthusiast who in single file when other users are present. Step off the loves a challenge or someone who simply enjoys a path when stopping. stroll, there’s a walking track that’s right for you. 2. Consider Others: Control your speed, slow down and use caution when approaching or overtaking other us- Rock hop along the Porirua coast and see the fabulous ers. Look behind when changing positions. Cyclists use Marlborough Sounds at sunset. Spot the rare wildfowl in hand signals. Don’t assume others can see or hear you. our bird sanctuary, or see how the whitebait are running. Follow the footsteps of the famous Te Rauparaha and his 3. -

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

Is it safe to swim in Porirua? Greater Wellington Regional Council and local councils monitor some of the Wellington region’s most popular beaches and rivers to determine their suitability for recreational activities such as swimming. We monitor eleven coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring are compared to national guidelines and used to calculate an overall grade for each site. Results from the 2014/15 summer season Recreational water quality in Porirua is quite variable with most sites having an overall grade of ‘C’. The best sites are at Karehana and Onehunga bays. These sites have an overall grade of ‘B’ and the Karehana Bay site met the guideline for safe swimming on all occasions. The worst sites were at the southern ends of Plimmerton Beach and Titahi Bay, and Te Awarua o Porirua Harbour at the Rowing Club. These sites recorded high bacterial counts on one occasion during the 2014/15 summer and have an overall grade of ‘D’. Very low risk of illness 0% Low risk 18% (2 sites) B Moderate risk 55% C (6 sites) Caution 27% (3 sites) D Unsuitable for swimming 0% In the Porirua area, 2 sites (18%) are graded ‘B’, 6 sites (55%) are graded ‘C’ and 3 sites (27%) are graded ‘D’. WAIT TWO DAYS AFTER RAIN before you swim again… Water quality at Porirua beaches is at its worst after heavy rain. Rain flushes contaminants from urban and rural land into water and we advise people not to swim for two days after heavy rain – even if a site generally has good water quality. -

Te Awarua-O- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme

Te Awarua-o- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee, April 2019 Front cover: Image of Porirua Harbour looking south Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua process is the collaborative discussion on the future of our streams and rivers, the water that connects us, the land and our communities, and how we manage and protect our natural resources. Stu Farrant Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Foreword from Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Like most areas of New Zealand, the communities within the Te Awarua-o-Porirua catchment have been defined by their intimate relationship with water. Early Māori established kāinga (villages) to utilise transformation of the catchment has been a steady the abundant mahinga kai (food harvested from decline in the quality of fresh and coastal waters and the streams, estuary and land) and other resources, the health of ecosystems. Contaminants are flushed travel routes and to seek protection from invaders. from urban and rural land and aging infrastructure Early European development rapidly spread struggles to serve the demands of a growing along the catchment’s streams and relied on the population, with overflows of wastewater a common reclamation of tidal margins for rail and road links occurrence during large rainfall events. These water and the development of what later became Porirua’s quality issues, coupled with extensive infilling and town centre and Elsdon. As the population grew, reclamation, have resulted in the severance of infrastructure was developed to drain stormwater and communities from the once abundant waterways and wastewater and protect the growing communities food and other resources they provided. -

Porirua – Our Place, Our Future, Our Challenge Let's Kōrero

COPYRIGHT © You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to Porirua City Council. Published March 2021. Porirua City Council 16 Cobham Court PO Box 50218 Porirua 5240 This document is available on our website poriruacity.govt.nz Porirua – our place, our future, our challenge Let’s kōrero Consultation Document for the proposed Long-term Plan 2021-51 Message from Ngāti Toa Rangatira E te iwi e noho nei i te riu o Porirua, tēnā koutou katoa The development of the city's Long-term Plan 2021-2051 will bring changes to our city that we will be proud of. Between now and 2051 we will see Porirua transform into a vibrant and exciting place to be for residents and people who choose to work here. We are blessed with hills, waterways, Te Mana o Kupe bushwalks and two magnificent harbours, Porirua and Pāuatahanui, as well as rich histories all anchored by Te Matahourua, the anchor left here by Kupe. As a challenge to all of us – we must look after our environment and look after each other, especially our tamariki and rangatahi. Nou te rourou, naku te rourou ka ora ai te Iwi With your contribution, and my contribution the people will thrive Taku Parai Chairman, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira 2 Consultation Document for the proposed LTP 2021-51 Contents Mai i tō Koutou Koromatua 4 From your Mayor Executive summary 8 Rates 10 The challenges for our city 11 Your views 16 Investment in the 3 waters – drinking water, wastewater 17 & stormwater 1. -

Your Guide to Summer 2019-20 Rangituhi Summit Photo: Jay French Walk and Walk Bike Bike Porirua Dogs Allowed

Discover Porirua Your guide to summer 2019-20 Rangituhi Summit Photo: Jay French Walk and Walk Bike bike Porirua Dogs allowed Celebrate the long, sunny days of summer with Ara Harakeke Titahi Bay Beach and a wide range of outdoor adventures in our 9.1km, 2 hr 30 min (one way) Southern Clifftop own big, beautiful backyard. We have lots of This track takes you through Mana, 2.8km, 1 hr (return) biking and hiking options to help you explore Plimmerton, and Pukerua Bay and If you’re after a mesmerising coastal includes four beaches, a wetland, view, this is the trail for you. Start Porirua’s great outdoors – from tamariki-friendly a steam train operation and historic at the south end of Titahi Bay strolls to challenging tracks for even the most World War II sites. The flat and Beach and then join the Southern easy track makes it particularly Clifftop Walk to enjoy views to seasoned and fearless mountain biker. popular for biking with tamariki. Mana Island and beyond. Te Ara Utiwai, Escarpment Track Te Ara Piko Whitireia Park Rangituhi 10km, 3-5 hr (one way) 3.2km, 50 min (one way) 6.5km, 1 hr 50 min (one way) 6.1km, 1 hr 45 min (one way) Stretching from Pukerua Bay to Take in the serene coastal wetland There are few tracks in New Zealand There are a range of tracks on Paekākāriki, this track will give atmosphere and the gorgeous inlet that can match the dramatic views the beautiful hills to the west of you bragging rights that you’ve views when you take the popular that Whitireia Park offers. -

Distribution of Geological Materials in Lower Hutt and Porirua, New Zealand a Component of a Ground Shaking Hazard Assessment

332 DISTRIBUTION OF GEOLOGICAL MATERIALS IN LOWER HUTT AND PORIRUA, NEW ZEALAND A COMPONENT OF A GROUND SHAKING HAZARD ASSESSMENT G. D. Dellow1 , S. A. L. Read 1 , J. G. Begg1 , R. J. Van Dissen1 , N. D. Perrin1 ABSTRACT Geological materials in the Lower Hutt, Eastbourne, Wainuiomata, and Porirua urban areas are mapped and described as part of a multi-disciplinary assessment of seismic ground shaking hazards. Emphasis is mainly on the flat-lying parts of these areas which are underlain by variable Quaternary-age sediments that overlie Permian-Mesowic age 'greywacke' bedrock. Within the Quaternary-age sediments, the two material types recognised on strength characteristics are: 1) Soft sediments, typically composed of normally consolidated, fine-grained materials (sand, silt and clay), with typical standard penetration values (SPT) of <20 blows/300 mm; and 2) Loose to compact coarser-grained materials (sand, gravel), with SPT values of > 20 blows/ 300 mm. The total thickness and nature of Quaternary-age sediments in the study areas is described, with particular emphasis on the thickness and geotechnical properties of near-surface sediments. Such sediments are considered likely to have a significant influence on the an1plification and attenuation of ground shaking intensity during earthquakes. In the Lower Hutt valley, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of -16 kni. Such soft sediments underlie much of Petone and the Lower Hutt urban and city centres, and have a maximum known thickness of 27 m near the western end of the Petone foreshore. In the Wainuiomata area, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of - 3 krn2, and attain a maximum thickness of 32 m. -

Coastal Water Quality and Ecology in the Wellington Region State and Trends

Coastal water quality and ecology in the Wellington region State and trends Coastal water quality and ecology in the Wellington region State and trends MD Oliver JR Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington Masterton GW/EMI-T-12/144 PO Box 11646 PO Box 41 ISBN: 978-1-927217-14-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-927217-15-3 (online) T 04 384 5708 T 06 378 2484 F 04 385 6960 F 06 378 2146 June 2012 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council (Greater Wellington) and as such does not constitute Council policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Greater Wellington does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Greater Wellington endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Greater Wellington requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. -

Te Awarua-O- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme

Te Awarua-o- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee, April 2019 Front cover: Image of Porirua Harbour looking south Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua process is the collaborative discussion on the future of our streams and rivers, the water that connects us, the land and our communities, and how we manage and protect our natural resources. Stu Farrant Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Foreword from Te Awarua-o-Porirua Whaitua Committee Chair Like most areas of New Zealand, the communities within the Te Awarua-o-Porirua catchment have been defined by their intimate relationship with water. Early Māori established kāinga (villages) to utilise transformation of the catchment has been a steady the abundant mahinga kai (food harvested from decline in the quality of fresh and coastal waters and the streams, estuary and land) and other resources, the health of ecosystems. Contaminants are flushed travel routes and to seek protection from invaders. from urban and rural land and aging infrastructure Early European development rapidly spread struggles to serve the demands of a growing along the catchment’s streams and relied on the population, with overflows of wastewater a common reclamation of tidal margins for rail and road links occurrence during large rainfall events. These water and the development of what later became Porirua’s quality issues, coupled with extensive infilling and town centre and Elsdon. As the population grew, reclamation, have resulted in the severance of infrastructure was developed to drain stormwater and communities from the once abundant waterways and wastewater and protect the growing communities food and other resources they provided.