Historical Snapshot of Porirua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foton International

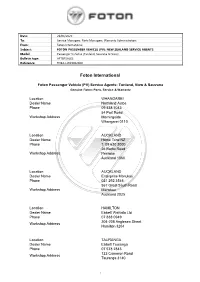

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

Parish with a Mission by Geoff Pryor

Parish with a Mission By Geoff Pryor Foreword - The Parish Today The train escaping Wellington darts first into one tunnel and then into another long, dark tunnel. Leaving behind the bustle of the city, it bursts into a verdant valley and slithers alongside a steep banked but quiet stream all the way to Porirua. It hurtles through the Tawa and Porirua parishes before pulling into Paremata to empty its passengers on the southern outskirts of the Plimmerton parish. The train crosses the bridge at Paremata with Pauatahanui in the background. There is no sign that the train has arrived anywhere particularly significant. There is no outstanding example of engineering feat or architecture, no harbour for ocean going ships or airport. No university campus holds its youth in place. No football stadium echoes to the roar of the crowd. The whaling days have gone and the totara is all felled. Perhaps once Plimmerton was envisaged as the port for the Wellington region, and at one time there was a proposal to build a coal fired generator on the point of the headland. Nothing came of these ideas. All that passed us by and what we are left with is largely what nature intended. Beaches, rocky outcrops, cliffs, rolling hills and wooded valleys, magnificent sunsets and misted coastline. Inland, just beyond Pauatahanui, the little church of St. Joseph, like a broody white hen nestles on its hill top. Just north of Plimmerton, St. Theresa's church hides behind its hedge from the urgency of the main road north. The present day parish stretches in an L shape starting at Pukerua Bay through to Pauatahanui. -

2021 Plimmerton School (2960) Charter Approved

School Charter, Strategic & Annual Implementation Plan 2021 - 2023 March 2021 1 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Contents Introductory Section Description of the school 3 Major historical developments 4 Motto and mission 5 Vision 6 Values 7 Cultural diversity and Maori dimension 8 National Education and Learning Priorities 9 Strategic Plan Section Strategic Plan 2021-23 10 Annual Plan Section Refer to separate Annual plan spreadsheet APPROVED: March 2021 Page 2 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Description of the School Plimmerton School is a year 1 to 8 decile 10 school with a roll close to 500 students at the year end. The school includes 14% Maori students, 4% Pasific Peoples, 7% Asian, 73% NZ European, and 3% of other ethnic groups. Nestled in the coastal town of Plimmerton, north of Porirua city, we enjoy a unique combination of village community lifestyle, and the advantages of close proximity to city life. We are set 300m from the sea on a large site. Facilities include 23 classrooms, a field, a large hall/auditorium, a heated covered swimming pool, a technology centre, and a new library completed in 2020. Local iwi The original settlement of Hongoeka, today an active Ngati Toa marae with a wharenui, provides cultural richness and opportunity to the Plimmerton community. We share a close association with local iwi and Hongoeka, with a representative co-opted to the Board of Trustees. The school fosters participation and success of Maori students through Maori educational initiatives consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi such as the instruction in tikanga Maori and Te Reo Maori. -

Paremata School Newsletter Thursday 2Nd February 2012017777 Week 111

PAREMATA SCHOOL NEWSLETTER THURSDAY 2ND FEBRUARY 2012017777 WEEK 111 IMPORTANT DATES Monday 6th February SCHOOL CLOSED – Waitangi Day Wednesday 8 th February SCHOOL WILL CLOSE AT 12.30PM DUE TO STAFF FUNERAL Term Dates Term 1 - Thursday 2 nd February – Thursday 13 th April Term 2 – Monday 1st May – Friday 7th July Term 3 – Monday 24 th July – Friday 29th September Term 4 – Monday 16th October – Tuesday 19 th December (to be confirmed) Kia ora tatou Welcome back to school for 2017. We all hope you have had a lovely break and great to see all the children looking well rested and in most cases taller! As usual we have a very busy schedule and we look forward to a great term ahead. A very warm welcome to all our new families and to our new teacher Jenny Goodwin who joins us in Ruma Ruru for 2017. We hope you all settle in well and enjoy your time here. Sad News Unfortunately we start the year off with very sad news. Rod Tennant who has worked at Paremata and Russell School part time for many years and had only recently retired passed away suddenly yesterday afternoon. Rod was a highly valued and loved member of our school staff and also the husband of Trish Tennant our lovely Special Education Coordinator. We are all devastated with Rod's passing and send our love and prayers to Trish and the Tennant family. We have an area set up for Rod in the school office where you are welcome to leave cards and messages. -

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington This report has been prepared for Wellington City Council and is not intended for general publication or circulation. It is not to be reproduced without written agreement. We accept no responsibility to any party, unless specifically agreed by us in writing. We reserve the right, but will be under no obligation, to revise or amend our report in light of any additional information, which was in existence when the report was prepared, but which was not brought to our attention. Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Background 1. Background KPQ is strategically located in Ngauranga Gorge, on State Highway 1 within Wellington City. The quarry is a hard rock quarry extracting greywacke. The KPQ site also hosts: An asphalt plant owned and operated by Downer, and A concrete plant owned and operated by Allied Concrete in which Holcim has a 50% holding. There are long term supply agreements in place with these businesses which provide both long term stability and sales, with the advantage of having exposure to both roading and construction based sales. This provides balance if there are short term fluctuations in either market. There is reasonable ability to adjust production between either market. There are limited sources of aggregate material in the region. The greywacke rock resource reserves along the Wellington Fault have for many decades been the prime source of the hard rock quarried for use in the wider Wellington and Hutt Valley areas. Ngauranga Gorge has been quarried for over 100 years. 1920 Quarry activity in Ngauranga Gorge:Track & Stream (Alexander Turnbull Library) Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Regional Rock Resources and Alternatives 2. -

02 Whole.Pdf (2.654Mb)

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the pennission of the Author. 'UNREALISED PLANS. THE NEW ZEALAND COMPANY IN THE MANAWATU, 1841 - 1844.' A Research Exercise presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements f6r the Diploma in Social Sciences in History at Massey University MARK KRIVAN 1988 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have helped me in the course of researching and writing this essay. The staff of the following: Alexander Turnbull Library. National Archives. Massey University Library. Palmerston North Public Library, especially Mr Robert Ensing. Wellington District Office, Department of Lands and Survey, Wellington, especially Mr Salt et al. Mrs Robertson of the Geography Department Map Library, Massey University. all cheerfully helped in locating sources and Maps, many going out of their way to do so. Mr I.R. Matheson, P.N.C.C. Archivist, suggested readings and shared his views on Maori land tenure in the Manawatu. He also discussed the New Zealand Company in the Manawatu and the location of the proposed towns. He may not agree with all that is written here but his views are appreciated. Thanks to Dr. Barrie MacDonald, Acting Head of Department, for seeing it through the system. Thanks to Maria Green, who typed the final draft with professional skill. My greatest debt is to Dr. J.M.R. Owens, who supervised this essay with good humoured patience. He provided invaluable help with sources and thoughtful suggestions which led to improvements. -

WAIRAU RIVER ACCESS POINTS ᵴ = Swimming Spot ۩ = Toilet Ᵽ = Picnic Area ۩ Wairau Bar 1 Vehicle Access to the Northern Side of the Wairau River Mouth

NELSON / MARLBOROUGH REGION MARLBOROUGH / NELSON such as a Humpy, Irresistible or Royal Wulf. If the trout are are trout the If Wulf. Royal or Irresistible Humpy, a as such NEW ZEALAND NEW first choice. If the fish are rising try a size 12 to 16 dry fly fly dry 16 to 12 size a try rising are fish the If choice. first with a red and gold veltic or articulated trout being a good good a being trout articulated or veltic gold and red a with productive method. The trout will take any type of spinner spinner of type any take will trout The method. productive TM before the wind gets up. Spinning is a popular and and popular a is Spinning up. gets wind the before wind conditions. The best fishing is often in the morning morning the in often is fishing best The conditions. wind Supported by: Supported All fishing methods work well but can be depend upon upon depend be can but well work methods fishing All size and the occasional larger fish up to 3kg. to up fish larger occasional the and size Telephone (03) 544 6382 www.fishandgame.org.nz 6382 544 (03) Telephone fishery with good numbers of brown trout around the 1kg 1kg the around trout brown of numbers good with fishery P O Box 2173, Stoke, Nelson. Stoke, 2173, Box O P 66 Champion Rd, Richmond, Rd, Champion 66 available at the south eastern end of the pond. It is a reliable reliable a is It pond. the of end eastern south the at available the shoreline. -

PERKINS FARM ESCARPMENT REVEGETATION Nga Uruora

PERKINS FARM ESCARPMENT REVEGETATION Nga Uruora Concept Plan December, 2013 Perkins Farm Escarpment Revegetation: Nga Uruora Concept Plan Prepared by the Nga Uruora Committee PO Box 1 Paekakariki December 2013 Nga Uruora is a not-for-profit voluntary organisation on the Kapiti Coast of New Zealand with the aim of creating a continuous ribbon of bird-safe native forest running from Porirua through to Waikanae. The vision is to bring Kapiti Island’s dawn chorus back to the coast. www.kapitibush.org.nz December 2013 2 Perkins Farm Escarpment Revegetation: Nga Uruora Concept Plan Contents Our vision .................................................................................................................. 5 Summary ................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 7 Our approach ............................................................................................................ 8 How we prepared this report ................................................................................... 9 Our revegetation ideas ........................................................................................... 11 Waikakariki and Hairpin Gullies ............................................................................ 11 The current situation 11 Waikakariki Gully 12 Hairpin Gully 13 Retiring Waikakariki and Hairpin Gullies – the vegetation -

Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 Environment Management Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 J. R. Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington GW/EMI-G-10/164 PO Box 11646 December 2010 T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council and as such does not constitute Council’s policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Council does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Council endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Council requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. The report may be cited as: Milne, J. 2010. Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10. -

Intertidal Shellfish Survey in Te Awarua-O-Porirua Harbour (Onepoto Arm), November 2017

Intertidal shellfish survey in Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour (Onepoto Arm), November 2017 Prepared for GWRC June 2018 Prepared by : Warrick Lyon For any information regarding this report please contact: Warrick Lyon Research Technician Fisheries +64-4-386 0873 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie Wellington 6241 Phone +64 4 386 0300 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: 2018207WN Report date: June 2018 NIWA Project: WRC18302 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Dr Malcolm Francis Formatting checked by: Pauline Allen Approved for release by: Dr Rosemary Hurst © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 4 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................