Te Awarua-O- Porirua Whaitua Implementation Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foton International

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

Prospectus.2021

2021 PROSPECTUS Contents Explanation 1 Tuia Overview 2 Rangatahi Selection 3 Selection Process 4 Mayoral/Mentor and Rangatahi Expectations 6 Community Contribution 7 Examples 8 Rangatahi Stories 9 Bronson’s story 9 Maui’s story 11 Puawai’s story 12 Tuia Timeframes 14 Key Contacts 15 Participating Mayors 2011-2020 16 Explanation Tōia mai ngā tāonga a ngā mātua tīpuna. Tuia i runga, tuia i raro, tuia i roto, tuia i waho, tuia te here tāngata. Ka rongo te pō, ka rongo te ao. Tuia ngā rangatahi puta noa i te motu kia pupū ake te mana Māori. Ko te kotahitanga te waka e kawe nei te oranga mō ngā whānau, mō ngā hapū, mō ngā iwi. Poipoia te rangatahi, ka puta, ka ora. The name ‘Tuia’ is derived from a tauparapara (Māori proverbial saying) that is hundreds of years old. This saying recognises and explains the potential that lies within meaningful connections to: the past, present and future; to self; and to people, place and environment. The word ‘Tuia’ means to weave and when people are woven together well, their collective contribution has a greater positive impact on community. We as a rangatahi (youth) leadership programme look to embody this by connecting young Māori from across Aotearoa/New Zealand - connecting passions, aspirations and dreams of rangatahi to serve our communities well. 1 Tuia Overview Tuia is an intentional, long-term, intergenerational approach to develop and enhance the way in which rangatahi Māori contribute to communities throughout New Zealand. We look to build a network for rangatahi to help support them in their contribution to their communities. -

Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 Environment Management Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 J. R. Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington GW/EMI-G-10/164 PO Box 11646 December 2010 T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council and as such does not constitute Council’s policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Council does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Council endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Council requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. The report may be cited as: Milne, J. 2010. Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10. -

Porirua Stream Walkway

Porirua Stream Walkway Route Analysis & Definition Study Cover Image: The valley floor of Tawa, with the bridge at McLellan Street in the foreground, 1906 Tawa - Enterprise and Endeavour by Ken Cassells, 1988 Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Porirua Stream Walkway Scoping Report & Implementation Strategy Prepared By Opus International Consultants Limited Noelia Martinez Wellington Office Graduate Civil Engineer Level 9, Majestic Centre, 100 Willis Street PO Box 12 003, Wellington 6144, Reviewed By New Zealand Roger Burra Senior Transport Planner Telephone: +64 4 471 7000 Facsimile: +64 4 471 7770 Released By Bruce Curtain Date: 24 March 2009 Principal Urban Designer Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 © Opus International Consultants Limited 2008 March 2008 3 Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study March 2008 i Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Contents 1 Introduction APPENDIX A – Option Details ..........................................................................................35 1.1 Project Objectives.........................................................................................................3 1.2 Policy Context ...............................................................................................................4 APPENDIX B – Earthworks Comments ...........................................................................43 -

Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council November 2013 Cover Photo: Onepoto Arm, Porirua Harbour, January 2013. Te Onepoto Bay showing the constructed causeway restricting tidal flows. Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council by Leigh Stevens and Barry Robertson Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7001, Ph 021 417 936 0275 417 935, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii All photos by Wriggle except where noted otherwise. Contents Porirua Harbour - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 5 3. Results and Discussion . 10 Intertidal Substrate Mapping . 10 Changes in Intertidal Estuary Soft Mud 2008-2013. 13 Intertidal Macroalgal Cover. 14 Changes in Intertidal Macroalgal Cover 2008 - 2013 . 16 Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Changes in Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Saltmarsh Mapping . 21 Changes in Saltmarsh Cover 2008-2013 . 24 Terrestrial Margin Cover . 25 4. Summary and Conclusions . 27 5. Monitoring ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 6. Management . 28 7. Acknowledgements . 29 8. References . 29 Appendix 1. Broad Scale Habitat Classification Definitions. 32 List of Figures Figure 1. Likely extent of historical estuary and saltmarsh habitat in relation to Porirua Harbour today. 2 Figure 2. Porirua Harbour showing fine scale sites and sediment plates estab. in 2007/8, 2012, and 2013. 4 Figure 3. Visual rating scale for percentage cover estimates of macroalgae (top) and seagrass (bottom). 5 Figure 4. Map of Intertidal Substrate Types - Porirua Harbour, Jan. 2013. 11 Figure 5. Change in the percentage of mud and sand substrate in Porirua Harbour, 2008-2013. 13 Figure 6. -

Porirua City / [email protected] / P

SEPTEMBER 2018 PORIRUA CITY WWW.INTEREST.CO.NZ / [email protected] / P. 09 3609670 PORIRUA CITY HOME LOAN AFFORDABILITY REPORT September 2018 Home loan affordability is a measure of the proportion of take-home pay that is needed to make the mortgage payment for a typical household. If that is less than 40%, then a mortgage is considered ‘affordable’. The following are typical assessments for households at three stages of home ownership. FIRST HOME BUYERS 25-29 YOUNG FAMILY 30-34 OLDER FAMILY 35-39 First home buyers earn a medi- Young family buyers earn medi- Older family buyers earn medi- an income for their age group, an incomes in their age bracket, an incomes in their age brack- and buy a first quartile house and buy a median house in et, and buy a median house in in their area. Both parties work their area. One partner works their area. Both partners work full-time. half-time. full-time. Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay Take Home Septem- 33.1% Take Home Septem- 30.9% Take Home Septem- 21.0% Pay ber 18 Pay ber 18 Pay $1,588.95 ber 18 Septem- 28.5% $1,398.29 Septem- 33.5% $1,943.93 per Week per Week per Week Septem- 20.1% ber 17 ber 17 ber 17 Septem- 24.0% Septem- 28.5% Septem- 17.1% ber 16 ber 16 ber 16 This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple where both are aged 25–29 and are working full time, to buy a with a young family to move up the property ladder and buy their who are both aged 35-39 and working full time, to move up the home at the lower quartile price in Porirua City. -

1 Decision of the Otorohanga District Licensing Committee

OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE Application 018-0013 IN THE MATTER of the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act 2012 AND of an application by IN THE MATTER J & J Clark Limited trading as Kawhia General Store for the renewal of an off-licence pursuant to section 127 of the Act OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE Chairperson: Mrs S Grayson Members: Cr R Johnson, Mr R Murphy HEARING at the Te Awamutu Fire Station Hall on 7 July 2017 APPEARANCES Mrs J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited - Applicant Mr R Davies, counsel for J & J Clark Limited Miss N Petersen, Medical Officer of Health Mr K Tutty, Licensing Inspector Sergeant J Kernohan, Police HEARING at the Waipa District Council Chambers on 6 April 2018 APPEARANCES Mrs J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited – Applicant Mr J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited - Applicant Mr R Davies, counsel for J & J Clark Limited Mrs N Zeier, Medical Officer of Health Mrs M Fernandez, Licensing Inspector DECISION OF THE OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE 1. The off-licence 018/OFF/006/15 in respect of the premises situated at 29 Jervois Street, Kawhia and known as Kawhia General Store is renewed for a further period of 3 years. The licence may issue upon payment of the annual fee. 1 2. The present conditions of the licence are replaced as follows (a) Alcohol may be sold or delivered on Monday to Sunday, from 8.00am to 8.00pm. (b) No alcohol may be sold on the premises on Good Friday, Easter Sunday, Christmas Day, or before 1.00pm on Anzac Day. -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

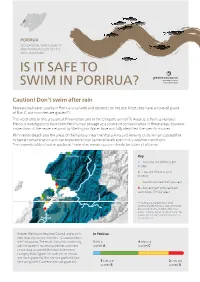

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site.