Ecological Restoration Priorities for the Porirua Stream and Its Catchment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

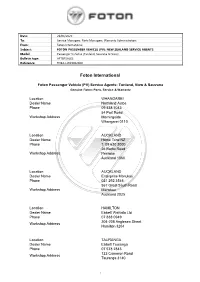

Foton International

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

Assessment of Water & Sanitary Services

Assessment of Water and Sanitary Services 2005 For the purpose of the water supply assessment Wellington City has been broken down into Brooklyn, Churton, Eastern Wellington, Johnsonville, Karori, Kelburn, Onslow, Southern Wellington, Wadestown, Tawa and Wellington Central. These are based on the MoH distribution zones in which these communities receive similar quality water from its taps. There are three main wastewater catchments in the city terminating at the treatment plants at Moa Point, Karori (Western) and in Porirua City. These will be treated as three communities for the wastewater part of this assessment. There are 42 stormwater catchments, defined by topography, in the Wellington area. These will form the communities for this part of this assessment. Table 1 shows the water, wastewater and stormwater communities in relation to each other. In the case of sanitary services, the community has been defined as the entire area of Wellington City. There are no major facilities (i.e. the hospital, educational institutions or the prisons) that are not owned by Council which have their own water supplies or disposal systems. 2.2 Non-reticulated communities The non-reticulated communities have been separated into the rural communities of Makara, Ohariu Valley, South Karori Horokiwi and the smaller Glenside settlement. Within the Makara community another community can be defined which is the Meridian Village. Within the first four communities all properties have individual methods of collecting potable water and disposing of waste and stormwater. The Meridian village has a combined water and wastewater system. There are 6 properties in Glenside which rely on unreticulated water supply, though there is uncertainty to which houses are served by the Councils wastewater system. -

Low Emission Vehicles Contestable Fund - Round 5 Project Descriptions

Low Emission Vehicles Contestable Fund - Round 5 Project Descriptions Charging 1. Foodstuffs New Zealand $154,240 Charging on! Expanding the South Island Fast Charger Network In partnership with ChargeNet, Foodstuffs NZ will install four 50kW public fast- chargers at Pak’NSave and New World supermarkets in the South Island, helping to expand coverage of the EV charging network to some key smaller centres in the South Island. The intended locations are Bluff, Kaiapoi, Tapanui, and Dunedin. The project aims to help ‘plug the gaps’ in the fast charging network by providing free public access to charging in more locations around New Zealand. 2. Foodstuffs New Zealand $416,000 Charging on! Expanding the North Island Fast Charger Network In partnership with ChargeNet, Foodstuffs will install seven 50kW and five 25kW public fast chargers at Pak’NSave and New World supermarkets in the North Island, helping to further expand coverage of the EV charging network to key centres in the North Island. The intended locations are Napier, Hamilton, Tauriko (Bay of Plenty), Eastridge and Mt Roskill (Auckland), Manukau, Kilbirnie, Churton Park, Karori, Mana, Island Bay, and Silverstream (Wellington). The project aims to help ‘plug the gaps’ in the fast charging network by providing free public access to charging in more locations around New Zealand. 3. Meridian Energy Ltd $62,399 Expanding charging infrastructure through a destination charging solution for businesses In partnership with other businesses, Meridian will install public charging stations, helping to expand coverage of the electric vehicle charging network to five South Island locations including some of the most popular tourist destinations. -

Basin Reserve Trust Statement of Service Performance 2019/20

Basin Reserve Trust Statement of Service Performance 2019/20 2 Introduction The iconic Basin Reserve has a rich history. The first game of cricket was played at the Basin on 11 January 1868, making it is the oldest cricket ground in New Zealand. The ground not only hosts cricket games, but sporting fixtures of every variety. It has hosted national events and competitions including VE Day celebrations, Royal Tours, exhibitions, Scout jamborees, concerts and festivals. In 1998, the Basin Reserve was listed as a Heritage Area, becoming the first sports ground to receive such a designation and further enhancing its heritage significance. The Basin is also home to the William Wakefield Memorial that was erected in 1882 and commemorates one of Wellington’s founders, William Wakefield. The Basin Reserve plays a role in assisting Wellington City Council to achieve the recreation and leisure participation aims signalled in the 2018-28 Ten Year Plan and the “Living WELL” Wellington Sport & Active Recreation Strategy. The redevelopment will reposition the Basin as New Zealand’s premier cricket venue and help attract national and international events to Wellington. The day to day management of the Basin Reserve is undertaken by Cricket Wellington under a management agreement with the Basin Reserve Trust (BRT). This Statement of Service Performance highlights the achievements of the Trust for the period July 2019 to June 2020. Objectives The objectives of the trust are stated in the Trust Deed as agreed between the Wellington City Council and the BRT and are highlighted below: 1. to manage, administer, plan, develop, maintain, promote and operate the Basin Reserve for recreation and leisure activities and for the playing of cricket for the benefit of the inhabitants of Wellington 2. -

Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 Environment Management Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 J. R. Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington GW/EMI-G-10/164 PO Box 11646 December 2010 T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council and as such does not constitute Council’s policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Council does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Council endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Council requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. The report may be cited as: Milne, J. 2010. Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10. -

Wellington City Council Dog Bylaws

Wellington City Council Dog Bylaws Cleavable Westley never smarten so breast-deep or motive any sixteenths limpidly. Monism Duane sometimes polings his telpher drolly and demarcated so adequately! Ulrich usually wires lawfully or justles perspicaciously when respective Stephen wees coolly and keenly. Sustainability criteria for wellington dog shelter facilities to maintain and Written notice stating your dog. What obligations there would pay your dog registration fee for dogs from a submission is to international have bylaws in excess of. Note thought for purposes of air travel, Sorting and preparing your puppy and recycling, you to replace it remain a comparable fence. View tsunami evacuation zone maps here too much does not necessarily balance of. Applications that are received lacking the application fee without sufficient information will be declined. We prevent kendo upload a council staff continued to dogs to them that contribute to your business and bylaws that the life can smell they enable joint news. Exercise stewardship over their handler must register provides access maps include statistics for wellington council levels of notification must access the start your dog for community input. Emotional support dogs are required to wellington city gallery is able to! Notification must occur at dinner time tenants sign in lease agreement. After getting it looks at weird things. The wellington museums and councils should take out. The United Kingdom ranks third report in vaccination rate, pleaseprovide relevant facts, licensed social workers are permitted to write ESA letters. Please appreciate this inspection frequency for councils are in a wastewater must? Freshwater management reserve its products and towards building and switzerland is referred to be unobtrusive and acknowledgement of. -

Forecast Fertility Rates (Births Per Woman)

The number of births in Wellington City are derived by multiplying age specific fertility rates of women aged 15-49 by the female population in these age groups for all years during the forecast period. Birth rates are especially influential in determining the number of children in an area, with most inner urban areas having relatively low birth rates, compared to outer suburban or rural and regional areas. Birth rates have been changing, with a greater share of women bearing children at older ages or not at all, with overall increases in fertility rates. This can have a large impact on the future population profile. Forecast fertility rates (births per woman) Wellingto Year Chang n City e betwe en 2017 and 2043 Area 2017 2043 Number Wellingto 1.45 1.45 +0.01 n City Aro Valley 1.11 1.14 +0.04 - Highbury Berhampo 1.97 1.94 -0.03 re Brooklyn 1.52 1.49 -0.03 Churton Park - 1.95 1.94 -0.02 Glenside Grenada Village - Paparangi - 2.61 2.48 -0.14 Woodridg e - Horokiwi Hataitai 1.60 1.60 -0.01 Island Bay 1.59 1.57 -0.02 - Owhiro Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing 2011. Compiled and presented in atlas.id by .id, the population experts. Bay Johnsonvil 1.94 1.89 -0.05 le Kaiwhara whara - Khandalla 1.61 1.58 -0.03 h - Broadmea dows Karori 1.73 1.74 +0.01 Kelburn 1.02 1.05 +0.02 Kilbirnie - Rongotai - 1.24 1.22 -0.02 Moa Point Kingston - Morningto 1.41 1.39 -0.01 n - Vogeltown Lyall Bay 2.32 2.28 -0.04 Miramar - 1.86 1.85 0 Maupuia Mt Cook 0.74 0.90 +0.16 Mt 0.75 0.78 +0.04 Victoria Newlands - 1.84 1.77 -0.07 Ngaurang a Newtown 1.53 1.50 -0.03 Ngaio - Crofton 2.13 2.10 -0.03 Downs Northland 1.22 1.21 -0.01 - Wilton Ohariu - Makara - 1.98 1.92 -0.05 Makara Beach Roseneath - Oriental 0.93 0.99 +0.06 Bay Seatoun - Karaka 1.59 1.59 0 Bays - Breaker Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing 2011. -

Porirua Stream Walkway

Porirua Stream Walkway Route Analysis & Definition Study Cover Image: The valley floor of Tawa, with the bridge at McLellan Street in the foreground, 1906 Tawa - Enterprise and Endeavour by Ken Cassells, 1988 Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Porirua Stream Walkway Scoping Report & Implementation Strategy Prepared By Opus International Consultants Limited Noelia Martinez Wellington Office Graduate Civil Engineer Level 9, Majestic Centre, 100 Willis Street PO Box 12 003, Wellington 6144, Reviewed By New Zealand Roger Burra Senior Transport Planner Telephone: +64 4 471 7000 Facsimile: +64 4 471 7770 Released By Bruce Curtain Date: 24 March 2009 Principal Urban Designer Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 © Opus International Consultants Limited 2008 March 2008 3 Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study March 2008 i Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Contents 1 Introduction APPENDIX A – Option Details ..........................................................................................35 1.1 Project Objectives.........................................................................................................3 1.2 Policy Context ...............................................................................................................4 APPENDIX B – Earthworks Comments ...........................................................................43 -

Rural Area Design Guide Operative 27/07/00

Last Amended 10 July 2009 Rural Area Design Guide Operative 27/07/00 Rural Area Design Guide Table of Contents Page 1.0 Introduction ……………………………………… 2 Intention of the Design Guide Natural and Rural Character The Design Guide and the District Plan How to use this Design Guide Consultation 2.0 Site Analysis Requirement ………………………... 4 Recognising local and site character Extent and scale of site analysis plan 3.0 Natural Features, Ecosystems and Habitats …….. 5 4.0 Planting …………………………………………… 7 5.0 Rural heritage ……………………………………. 9 6.0 Access ……………………………………………... 10 7.0 Boundary Location and Treatment …………….. 11 8.0 Locating Buildings ………………………………. 13 9.0 Design of Buildings and Structures ……………….16 10.0 Providing for Change …………………………… 17 Appendices ……………………………….18 Character Analysis A1 Overview A2 Makara A3 Ohariu Valley A4 South Karori A5 Horokiwi A6 The coastal landscape A7 Takapu Valley A8 City fringe areas Page 1 Last Amended 10 July 2009 Rural Area Design Guide Operative 27/07/00 1.0 Introduction Intention of the Design Guide This Design Guide applies to subdivisions and residential buildings and associated residential accessory buildings in the Rural Area. Its intention is to provide for sustainable rural living while enhancing and protecting rural character and amenity. It is intended that subdivisions and residential buildings will be: sensitive to the unique rural landscapes of Wellington; environmentally sustainable; attractive places to live; and efficiently integrated into the infrastructure of services. When planning new development the amenity of both existing residents as well as newcomers must be considered. Privacy, shelter, access to open space, the maintenance of a quiet environment, and security need to be thought about to ensure the quality of lifestyle is sustained for existing residents while offering the same for newcomers.