Porirua's Physical Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish with a Mission by Geoff Pryor

Parish with a Mission By Geoff Pryor Foreword - The Parish Today The train escaping Wellington darts first into one tunnel and then into another long, dark tunnel. Leaving behind the bustle of the city, it bursts into a verdant valley and slithers alongside a steep banked but quiet stream all the way to Porirua. It hurtles through the Tawa and Porirua parishes before pulling into Paremata to empty its passengers on the southern outskirts of the Plimmerton parish. The train crosses the bridge at Paremata with Pauatahanui in the background. There is no sign that the train has arrived anywhere particularly significant. There is no outstanding example of engineering feat or architecture, no harbour for ocean going ships or airport. No university campus holds its youth in place. No football stadium echoes to the roar of the crowd. The whaling days have gone and the totara is all felled. Perhaps once Plimmerton was envisaged as the port for the Wellington region, and at one time there was a proposal to build a coal fired generator on the point of the headland. Nothing came of these ideas. All that passed us by and what we are left with is largely what nature intended. Beaches, rocky outcrops, cliffs, rolling hills and wooded valleys, magnificent sunsets and misted coastline. Inland, just beyond Pauatahanui, the little church of St. Joseph, like a broody white hen nestles on its hill top. Just north of Plimmerton, St. Theresa's church hides behind its hedge from the urgency of the main road north. The present day parish stretches in an L shape starting at Pukerua Bay through to Pauatahanui. -

2021 Plimmerton School (2960) Charter Approved

School Charter, Strategic & Annual Implementation Plan 2021 - 2023 March 2021 1 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Contents Introductory Section Description of the school 3 Major historical developments 4 Motto and mission 5 Vision 6 Values 7 Cultural diversity and Maori dimension 8 National Education and Learning Priorities 9 Strategic Plan Section Strategic Plan 2021-23 10 Annual Plan Section Refer to separate Annual plan spreadsheet APPROVED: March 2021 Page 2 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Description of the School Plimmerton School is a year 1 to 8 decile 10 school with a roll close to 500 students at the year end. The school includes 14% Maori students, 4% Pasific Peoples, 7% Asian, 73% NZ European, and 3% of other ethnic groups. Nestled in the coastal town of Plimmerton, north of Porirua city, we enjoy a unique combination of village community lifestyle, and the advantages of close proximity to city life. We are set 300m from the sea on a large site. Facilities include 23 classrooms, a field, a large hall/auditorium, a heated covered swimming pool, a technology centre, and a new library completed in 2020. Local iwi The original settlement of Hongoeka, today an active Ngati Toa marae with a wharenui, provides cultural richness and opportunity to the Plimmerton community. We share a close association with local iwi and Hongoeka, with a representative co-opted to the Board of Trustees. The school fosters participation and success of Maori students through Maori educational initiatives consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi such as the instruction in tikanga Maori and Te Reo Maori. -

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington This report has been prepared for Wellington City Council and is not intended for general publication or circulation. It is not to be reproduced without written agreement. We accept no responsibility to any party, unless specifically agreed by us in writing. We reserve the right, but will be under no obligation, to revise or amend our report in light of any additional information, which was in existence when the report was prepared, but which was not brought to our attention. Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Background 1. Background KPQ is strategically located in Ngauranga Gorge, on State Highway 1 within Wellington City. The quarry is a hard rock quarry extracting greywacke. The KPQ site also hosts: An asphalt plant owned and operated by Downer, and A concrete plant owned and operated by Allied Concrete in which Holcim has a 50% holding. There are long term supply agreements in place with these businesses which provide both long term stability and sales, with the advantage of having exposure to both roading and construction based sales. This provides balance if there are short term fluctuations in either market. There is reasonable ability to adjust production between either market. There are limited sources of aggregate material in the region. The greywacke rock resource reserves along the Wellington Fault have for many decades been the prime source of the hard rock quarried for use in the wider Wellington and Hutt Valley areas. Ngauranga Gorge has been quarried for over 100 years. 1920 Quarry activity in Ngauranga Gorge:Track & Stream (Alexander Turnbull Library) Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Regional Rock Resources and Alternatives 2. -

Annual Coastal Monitoring Report for the Wellington Region, 2009/10

Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 Environment Management Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10 J. R. Milne Environmental Monitoring and Investigations Department For more information, contact Greater Wellington: Wellington GW/EMI-G-10/164 PO Box 11646 December 2010 T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Monitoring and Investigations staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council and as such does not constitute Council’s policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, Council does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as Council endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. Council requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. Any use of the data and information enclosed in this report, for example, by inclusion in a subsequent report or media release, should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source. The report may be cited as: Milne, J. 2010. Annual coastal monitoring report for the Wellington region, 2009/10. -

PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1

PLIMMERTON FARM – PLAN CHANGE PROPOSAL Supporting Documentation View from Submitters Property Karla and Trevor Beamsley 24 Motuhara Road Plimmerton PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION The village of Plimmerton is a northern suburb of Porirua, and is surrounded to the North and East by farmland. It represents the edge of existing residential dwellings. Generally existing homes are stand-alone dwellings on lots greater than 500m² in size. Most residents within Plimmerton and Camborne either commute into Wellington city or work from home. The demand for housing in this area is from professional couples or families looking for 3 – 4 bedroom family homes on a section with space for kids to run around in, not medium or high density three-storey buildings and apartments, this is reflected in the TPG report to PCC (Dec 2019). Medium density style townhouses, or apartments would be totally out of character of the surrounding residential areas, and would present a stark contrast to the remaining rural areas which bound the site. The Plimmerton Farm site is not located close to areas of high employment, nor is it close to local amenities like the main shopping areas of Porirua. The site is also not located within an area currently supported by existing infrastructure. Much of the infrastructure in the area is aging, and requires repair or upgrade to support existing demands. Therefore, the idea that Plimmerton Farm would provide homes in a location close to employment, amenities and infrastructure1 is simply incorrect in terms of a 10-year time frame. Areas where this would be true include the currently developing areas of Aotea, Whitby, Kenepuru, and Porirua East. -

GROUNDUP CAFÉ SUBMISSION - ADDENDUM by Pauatahanui Residents Association

GROUNDUP CAFÉ SUBMISSION - ADDENDUM by Pauatahanui Residents Association This paper is prepared for the Pauatahanui Residents Association’s oral Submission to the Hearing on the GroundUp Cafe’s retrospective application for Resource Consent to legalise building extensions and additional Cafe seating capacity from 35 to 65. This updates our original submission of February 2014 , and includes responses to subsequent information received from the applicant and Porirua City Council and since our original submission was made some issues have changed. TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT GroundUp Café (the Café ) Rural Trading Post (the Trading Post ) Pauatahanui General Store (the Store ) Porirua City Council ( PCC ) Pauatahanui Residents Association ( PRA ) BACKGROUND • The PRA is: o A voluntary organization started as an Incorporated society in 1975. o A registered charity 1 since June 2008 o Its objectives include 3a) to maintain or improve the community and its environment for all residents while preserving its rural character and scenery. • There are approximately 300 households in the Pauatahanui area. The Association currently has 57 paid up member households. It has 177 people registered on its mailing list for monthly newsletters or notices. Newsletters are also circulated to other groups who distribute them more widely to their members. Notices and newsletters are also posted on PRA’s website 2. PRA’s original submission has been available on this website since February 2014. 1 Registered Charity Number CC42516 2 www.pauatahanui.org.nz Pauatahanui Residents Association (PRA) Version: 17/11/2014 - Page 1 Application on GroundUp Café Submission (Addendum) – Lot 1 DP7316 at 15 Paekakariki Hill Road, Pauatahanui • In addition, PRA uses the Rural Delivery to periodically share information or invite comment on important issues sent out as a community notice to all 300 households. -

Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council November 2013 Cover Photo: Onepoto Arm, Porirua Harbour, January 2013. Te Onepoto Bay showing the constructed causeway restricting tidal flows. Porirua Harbour Broad Scale Habitat Mapping 2012/13 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council by Leigh Stevens and Barry Robertson Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7001, Ph 021 417 936 0275 417 935, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii All photos by Wriggle except where noted otherwise. Contents Porirua Harbour - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 5 3. Results and Discussion . 10 Intertidal Substrate Mapping . 10 Changes in Intertidal Estuary Soft Mud 2008-2013. 13 Intertidal Macroalgal Cover. 14 Changes in Intertidal Macroalgal Cover 2008 - 2013 . 16 Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Changes in Intertidal Seagrass Cover . 17 Saltmarsh Mapping . 21 Changes in Saltmarsh Cover 2008-2013 . 24 Terrestrial Margin Cover . 25 4. Summary and Conclusions . 27 5. Monitoring ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 6. Management . 28 7. Acknowledgements . 29 8. References . 29 Appendix 1. Broad Scale Habitat Classification Definitions. 32 List of Figures Figure 1. Likely extent of historical estuary and saltmarsh habitat in relation to Porirua Harbour today. 2 Figure 2. Porirua Harbour showing fine scale sites and sediment plates estab. in 2007/8, 2012, and 2013. 4 Figure 3. Visual rating scale for percentage cover estimates of macroalgae (top) and seagrass (bottom). 5 Figure 4. Map of Intertidal Substrate Types - Porirua Harbour, Jan. 2013. 11 Figure 5. Change in the percentage of mud and sand substrate in Porirua Harbour, 2008-2013. 13 Figure 6. -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

12 Schedules Schedules 12 Schedules

12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules contents Schedule Page number Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies A1-A3 279 Schedule B: Ngā Taonga Nui a Kiwa B 281 Schedule C: Sites with significant mana whenua values C1-C5 294 Schedule D: Statutory Acknowledgements D1-D2 304 Schedule E: Sites with significant historic heritage values E1-E5 333 Schedule F: Ecosystems and habitats with significant indigenous biodiversity values F1-F5 352 Schedule G: Principles to be applied when proposing and considering mitigation and G 407 offsetting in relation to biodiversity Schedule H: Contact recreation and Māori customary use H1-H2 410 Schedule I: Important trout fishery rivers and spawning waters I 413 Schedule J: Significant geological features in the coastal marine area J 415 Schedule K: Significant surf breaks K 418 Schedule L: Air quality L1-L2 420 Schedule M: Community drinking water supply abstraction points M1-M2 428 Schedule N: Stormwater management strategy N 431 Schedule O: Plantation forestry harvest plan O 433 Schedule P: Classifying and managing groundwater and surface water connectivity P 434 Schedule Q: Reasonable and efficient use criteria Q 436 Schedule R: Guideline for stepdown allocations R 438 Schedule S: Guideline for measuring and reporting of water takes S 439 Schedule T: Pumping test T 440 Schedule U:Trigger levels for river and stream mouth cutting U 442 PROPOSED NATURAL RESOURCES PLAN FOR THE WELLINGTON REGION (31.07.2015) 278 Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies Schedule A1: Rivers with outstanding indigenous ecosystem -

Paremata Village Plan 2012

Paremata Village Plan 2012 1 Introduction It’s my very great pleasure to introduce this first edition of the Paremata Village Plan, covering the suburbs of Paremata (which now includes Mana) and Papakowhai. Our plan has been developed in accordance with the Porirua City Council (PCC) Village Planning Programme, an award-winning Council initiative to improve and develop Porirua’s suburban communities through work programmes developed in partnership with the people of those communities. For further information on the Village Planning Programme please go to the PCC Website www.pcc.govt.nz and search under Community, Village Planning. I would like to thank on your behalf the PCC Villages Programme manager Ian Barlow and his team for all the work they have done to get this plan off the ground. My thanks in particular to Jenny Lester, who has been our liaison person and has taken on most of the development work including running surveys of residents to build a picture of what we want our ‘village’ to look like in future. A huge thank you to the 300+ residents who participated in the concept, development, content and comments used in this plan. Here is our template for that vision, now it’s up to us all to contribute to making that vision a reality. Terry Knight President Paremata Residents Association Vision Statement Paremata – where community and environment are in harmony, protecting the best of what we have and embracing the best of what’s new. About Paremata The area covered by the Paremata Residents Association takes in several suburbs; Paremata, Papakowhai, Mana and a section of Camborne. -

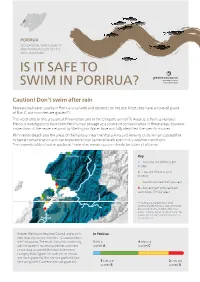

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site. -

Paremata Residents Association Presentation to TGP Board of Inquiry – 6 March 2012

Paremata Residents Association Presentation to TGP Board of Inquiry – 6 March 2012 1. My name is Russell Morrison and I am the Vice-President of the Paremata Residents Association which covers an area of about 2,100 households encompassing Papakowhai, Paremata, Golden Gate, Mana and part of Camborne. I have lived in residences right next to the Pauatahanui Inlet and used the harbour in many different ways since the age of two when my family moved to Browns Bay in January 1950. 2. Our Association strongly supports the TGP and has been prepared to go to the Environment Court on three occasions in the past to ensure, directly or indirectly, that TGP stayed on the books. We are asking, however, that the Board consider imposing conditions in a number of areas. Adverse Impacts on the Harbour 3. Our submission mentions our concerns about the harbour but does not go into much detail, opting instead simply to endorse the recommendations of the Pauatahanui Inlet Community Trust (PICT) entirely. I would like to elaborate on our views here. - Sedimentation 4. Quite a number of our members have lived next to the Porirua Harbour for many years. We recall the controversy when the initial Whitby subdivision was pouring sediment out onto the beach opposite what is now Postgate Drive. Many still mention the promises about retaining tidal flows when the highway was extended and the lagoons created between Porirua and Paremata. We remember the learned debates which took place when the National Roads Board proposed putting a 6 lane motorway on a causeway along the Dolly Varden beach and up through Camborne.