Villagers on the Move: Re-Thinking Fallahin Rootedness in Late-Ottoman Palestine Above

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Theme and the Function of the Verb in Palestinian Arabic Narrative Discourse

THEME AND THE FUNCTION OF THE VERB IN PALESTINIAN ARABIC NARRATIVE DISCOURSE BY ILHAM NAYEF ABU-GHAZALEH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1983 , To my sister SHADYIA, who refused to continue her studies at Cairo University after the final occupation of Palestine in 1967 - She said, before she was killed at the age of -nineteen "WHAT IS THE USE OF A UNIVERSITY DEGREE FOR A PALESTINIAN WHEN HE HAS NO WALL TO HANG IT ON?" . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thankfulness to the head of my committee, Dr. Chauncey Chu, is limitless. I am greatly indebted to him for his tireless devotion and generosity in giving of his valuable time to crystallize this work. His kind and patient encourage- ment has been an important factor in my academic growth. My gratitude also goes to the rest of the members of my committee. Dr. Alice Faber's comments, guidance and sup- port sharpened my perception in this analysis. Dr. Bill Sullivan enriched my analysis by helping me see other sides to it. Dr. Robert de Beaugrande always enabled me to put things into perspective through his discussions, concern and encouragement. My discussions with Dr. Rene LeMarchand were of great importance to me. My greatest thanks and love go to my home university, Birzeit, for providing me with this opportunity for growth and enrichment. The difficulties they were enduring while I was far from them constituted a heavy part of my personal suffering To all my friends in Gainesville, in the United States, and at home, go my unlimited love and gratitude. -

F-Dyd Programme

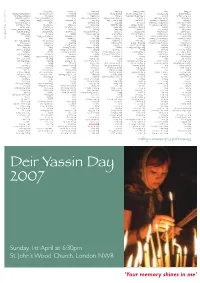

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

Rehabilitation of Waqf Foundation in Jerusalem During the Third and Fourth Decade of the Seventeenth Century (1620-1640)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 10; August 2014 Rehabilitation of Waqf Foundation in Jerusalem during the Third and Fourth Decade of the Seventeenth Century (1620-1640) Dr. Ibrahim Rabayeh Al-Quds open University Tulkarm Dr. Mohammad Khateeb An-Najah National University Nablus Abstract At the time were Judaization of Jerusalem targets all what express the history of this city materially or morally, it was necessary to disclose some historical facts on few Jerusalemite institutions and Foundations which reflects its civilized Arab roots, including but not limited to, the Waqf Foundation which has preserved life continuity in the city through long periods of time. Accordingly, this research aims at studying the real condition of Waqf (Religious endowment) in Jerusalem, at the first mid of the seventh century, being an expressive model of this foundation and its role during this Period. Upon perusing the archive resources, represented in the Ottoman Registers at the Sharia court of Jerusalem, it was obvious that they are abounding in information which describe the status which the Waqf Foundations have reached and therefore its impact on Jerusalem in general. In addition the research aims at revealing the significance of this Foundation at the time were Israel tries to control all its properties and to hinder its efforts to undermine it to become nonfunctioning, which make it easier to submit it to be under the Israeli control. Providing that undermining this Foundation means harming a large segment of Jerusalemites, particularly the poor and orphans, as well as the education process for which a considerable Waqf( endowment) was dedicated. -

Financing Racism and Apartheid

Financing Racism and Apartheid Jewish National Fund’s Violation of International and Domestic Law PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY August 2005 Synopsis The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is a multi-national corporation with offices in about dozen countries world-wide. It receives millions of dollars from wealthy and ordinary Jews around the world and other donors, most of which are tax-exempt contributions. JNF aim is to acquire and develop lands exclusively for the benefit of Jews residing in Israel. The fact is that JNF, in its operations in Israel, had expropriated illegally most of the land of 372 Palestinian villages which had been ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces in 1948. The owners of this land are over half the UN- registered Palestinian refugees. JNF had actively participated in the physical destruction of many villages, in evacuating these villages of their inhabitants and in military operations to conquer these villages. Today JNF controls over 2500 sq.km of Palestinian land which it leases to Jews only. It also planted 100 parks on Palestinian land. In addition, JNF has a long record of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as reported by the UN. JNF also extends its operations by proxy or directly to the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the West Bank and Gaza. All this is in clear violation of international law and particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids confiscation of property and settling the Occupiers’ citizens in occupied territories. Ethnic cleansing, expropriation of property and destruction of houses are war crimes. As well, use of tax-exempt donations in these activities violates the domestic law in many countries, where JNF is domiciled. -

18 June 2008 VALUATION of PALESTINIAN REFUGEE LOSSES

VALUATION OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEE LOSSES A Study Based on the National Wealth of Palestine in 1948 Thierry J. Sene chal 18 June 2008 Page 2 of 260 Contact information: Thierry J. Senechal [email protected] Tel. +33 6 24 28 51 11 This report is established by request of the Negotiations Support Unit (NSU), Negotiations Affairs Department of the PLO/Palestinian Authority. The views expressed in this report are those of the Advisor and in no way reflect the official opinion of the commissioning unit. This report has been prepared for the use of the NSU in connection with its estimation of Palestinian Refugees’ losses arising out of the 1948 war and should not be used by other parties or for other purposes. The views expressed in the following review are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the NSU. The author would like to express his gratitude to Philippe de Mijolla for his continuous support on this project. Privileged and Confidential Thierry Senechal, 18 June 2008 Page 3 of 260 STRATEGIC SUMMARY of this study) can make an informed OBJECTIVES assessment of the level of judgment (if any) that has been used in deriving values. In addition, a full audit trail is integral to study. This report forms the third phase of a project which provides a quantification of In Section 1 of the report, we introduced the aggregate value of losses incurred by the scope of reference of our work and key Palestinian Arab refugees as a result of their findings from our initial review of past forced displacement from what is now estimates. -

Supplement Bo. 2 Cf)E Palestine <Sa?Ette Bo. Nm of Istj $®Ml>, 1945

Supplement Bo. 2 ta Cf)e Palestine <sa?ette Bo. nm of istj $®ml>, 1945. PALESTINE ORDER IN COUNCIL, 1922. PROCLAMATION BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER UNDER ARTICLE 11. IN EXERCISE of the powers vested in me by Article 11 of the Palestine Order in Council, 1922, I, SIR HAROLD ALFRED MACMICHAEL, G.C.M.G., D.S.O., High Commissioner for ־—:Palestine, with the approval of the Secretary of State, do hereby proclaim as follows 1. This Proclamation may be cited as the Administrative Divisions Citation. (Amendment) Proclamation, 1943, and shall be read as one with the Administrative Divisions Proclamation, 1939, hereinafter referred to Gaz: 30.12.39, as the principal Proclamation. p. 1529. 2. The Schedule to the principal Proclamation shall be revoked, and Eevocation and the Schedule hereto shall be substituted therefor: — replacement of Schedule to principal pro clamation. 3. This Proclamation shall be deemed to have come into force on the Commencement. 1st January, 1943. THE SCHEDULE. A. GALILEE DISTRICT. 1. Acre SubDistrict. Abu Sin&n Jatt Nahf Acre Judeida Nahr, En 'Amqa Jûlis Nahariya 'Arraba Kâbûl Rama, Er f Bassa, El and Ma'sub Kafr I nân Ruweis, Er Beit Jann and 'Ein el Asad Kafr Sumei' Sâjûr Bi'na, El Kafr Yâsîf Sakhnîn Birwa, El Khirbat Jiddîn Sha'ab Buqei'a, El Khirbat Samah (Eilon) Suhmâtâ Damun, Ed Kisrâ Sumeirîya, Es Deir el Asad Kuweikât Tamra Deir Hanna Majd el Kurûm Tarbîkhâ (includes En Fassuta and Deir el Qasi Makr, El Nabî Rûbîn and Surûh) and El Mansura Manshîya Tarshîha and Kâbrî Ghabisiya, El and Sheikh Mazra'a, El and Shave Umm el Faraj Dawud (includes Sheikh Zion and 'Ein Sara and Yânûh Dannun) Ga'aton Yirkâ Hanita Mî'âr Zîb, Ez (includes Mana Iqrit Mi'ilyâ wât) — 215 — 216 THE PALESTINE GAZETTE NO. -

Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine (1648-1650) Also Known As Çelebi

Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine (1648-1650) Also known as Çelebi. Translator from Turkish: Stephan Hanna Stephan. The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. Published for the government of Palestine by G. Cumberledge, Oxford University Press, London Part 1. Vol 4 (1935) 103–108. Annotation by L. A. Mayer. Part 2. Vol 4 (1935) 154–164. Annotation by L. A. Mayer. Part 3. Vol 5 (1936) 69–73. Annotation by L. A. Mayer.. Part 4. Vol 6 (1937) 84–97. Annotation by L. A. Mayer. Part 5. Vol 8 (1939) 137–156. Part 6. Vol 9 (1942) 81–104. The year is uncertain for the last two parts. Vol 9 was published over several years. Part 6 ends with "to be continued" but there was apparently no Part 7. EVLIYA TSHELEBI'S TRAVELS IN PALES TINE VLIYA MEHMED ZILLI B. DERVISH (A.D. I6I Iji2-I679), better known Eas Evliya Tshelebi, travelled for 'over thirty years through seventeen countries'. Of the ten volumes of his travels, called Seyahat-name',eight have been published so far, and the first two translated. He visited Palestine twice, the first time in I059 A.H. (towards the end of A.D. I649), and again in I07I A. H. (A.D. I67o-I ), when he continued his way to Mecca in order to perform his pilgrimage. He was a pious Moslem, anxious to recite his prayers at every site with which holy memories were connected, on the whole firmly believing in whatever his guides told him. It is the fact that he visited so many of these sites which makes his account particularly' valuable to the archaeologist who seeks information about the monuments of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and to the folk-lorist who collects legends and local interpretations of Qur'anic stories. -

Meet Handala

Welcome. Meet Handala Handala is the most famous of Palestinian political cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s characters. Depicted as a ten- year old boy, he first appeared in 1969. In 1973, he turned his back to the viewer and clasped his hands behind his back. The artist explained that the ten-year old Handala represented his age when he was forced to leave Palestine and would not grow up until he could return to his homeland; his turned back and clasped hands symbolised the character’s rejection of “outside solutions.” He wears ragged clothes and is barefoot, symbolising his allegiance to the poor. Handala remains an iconic symbol of Palestinian identity and defiance. Let him share his story with you. This series of educational panels is offered as an introduction to a deeper understanding of both the history and present realities of the Palestinian struggle for justice. We believe that the facts have been largely presented in a biased and misleading way in the mainstream media, leaving many people with an incomplete and often incorrect understanding of the situation. Please take a few minutes to stroll through our exhibit. Please open your hearts and minds to a larger picture of the conflict. Zionism: the root of the Israeli - Palestinian conflict. Zionism, in its political manifestation, is committed to the belief that it is a good idea to establish, in the country of Palestine, a sovereign Jewish state that attempts to guarantee, both in law and practice, a demographic majority of ethnic Jews in the territories under its control. Political Zionism claims to offer the only solution to the supposedly intractable problem of anti-Semitism: The segregation of Jews outside the body of non-Jewish society. -

![The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9550/the-birth-of-the-palestinian-refugee-problem-revisited-2nd-edition-6959550.webp)

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]

THE BIRTH OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM REVISITED Benny Morris’ The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, was first published in 1988. Its startling reve- lations about how and why 700,000 Palestinians left their homes and became refugees during the Arab–Israeli war in 1948 undermined the conflicting Zionist and Arab interpreta- tions; the former suggesting that the Palestinians had left voluntarily, and the latter that this was a planned expulsion. The book subsequently became a classic in the field of Middle East history. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited represents a thoroughly revised edition of the earlier work, compiled on the basis of newly opened Israeli military archives and intelligence documentation. While the focus of the book remains the 1948 war and the analysis of the Palestinian exodus, the new material con- tains more information about what actually happened in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, and how events there eventually led to the collapse of Palestinian urban society. It also sheds light on the battles, expulsions and atrocities that resulted in the disintegration of the rural communities. The story is a harrowing one. The refugees now number some four million and their existence remains one of the major obstacles to peace in the Middle East. Benny Morris is Professor of History in the Middle East Studies Department, Ben-Gurion University.He is an outspo- ken commentator on the Arab–Israeli conflict, and is one of Israel’s premier revisionist historians. His publications include Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist–Arab Conflict, 1881–2001 (2001), and Israel’s Border Wars, 1949–56 (1997).