Das Opernglas – November, 2013, Issue Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr. 9 – 01/2019 – deutsch – english – français Wir möchten die Ortsverbände höflich bitten, zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten und Veranstaltungsankündigungen diese Links zu benutzen Link zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten für die RWVI Webseiten: http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-news/ Link zur Übermittlung von Veranstaltungshinweisen für die RWVI Webseiten. http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-event/ Danke für ihre Mithilfe. Liebe Wagnergemeinde weltweit, In den letzten zwei Jahren galt es für die Wagnergemeinde viele wichtige Geburtstage zu feiern. Nicht nur gab es Gedenktage von Birgit Nilsson und Astrid Varnay, sondern auch diejenigen einiger Mitglieder der Wagner Familie: Im Jahre 2017 Wieland Wagner (100 Jahre), im Jahre 2018 Cosima Wagner (180 Jahre), Siegfried Wagner (150 Jahre) sowie Friedelind Wagner (100 Jahre). Solche Jubiläen geben Anlass zu Rückblick und Neubetrachtungen über die Bedeutung und den Einfluss der Jubilierten für die Bayreuther Festspiele. Feierveranstaltungen zu ihren Ehren fanden unter anderem auch zweimal in Berlin statt. Im Jahre 2017 und 2018 wurde jeweils ein RWVI-Symposium durchgeführt, liebevoll organisiert vom Richard Wagner Verband Berlin-Brandenburg. Im 2019 besteht erneut Anlass zum Feiern, diesmal 100 Jahre Wolfgang Wagner. In seinem Buch „Weisst du wie es ward“ berichtet Josef Lienhart, der Ehrenpräsident des RWVI, wie Wieland Wagner schon nach der Wiedergründung des RWV (deutscher Bundesverband) im Jahr 1945 die Meinung vertrat, „dies könne letztlich nur international möglich sein“. Es hat aber bis 1991 gedauert bis der Richard Wagner Verband International (RWVI) gegründet wurde. Der RWVI hatte in den ersten Jahrzehnten mit Wolfgang Wagner als Festspielleiter zu tun. Die Internationalisierung war sehr in dessem Sinne. -

Silberne Lieder

Das Klassik & Jazz Magazin 2/2014 Pumeza Matshikiza : Township und Opernbühne Carl Philipp Emanuel zum 300. : Der schwarze Bach Klaus Florian Vogt : Keine Schluchzer ! Artemis Quartett & Cuarteto Casals : Streichquartett- Frühling CHRISTIANE KARG Silberne Lieder Immer samstags aktuell www.rondomagazin.de © Yossi Zwecker © Yossi Juni 2014 La Traviata auf Masada. Kommen Sie nach Israel und lassen Sie sich von einem einmaligen Opern-Erlebnis der Extraklasse verzaubern. Vom 12. bis 17. Juni 2014 verwandelt sich das beeindruckende Felsplateau Masada wieder in eine spektakuläre Opernbühne unter freiem Himmel. Genießen Sie die unvergessliche Au ührung von Verdis La Traviata am Fuße dieser atemberaubenden Naturkulisse und erleben Sie hautnah, welche Wunder Israel für Sie bereithält. Besuch Israel Besuch Israel Erleben Sie die faszinierende Vielfalt Israels. www.goisrael.de Faszinierend bunt. 2 © Yossi Zwecker © Yossi Themen Café Imperial: Stammgast im Wiener Pasticcio: Musiker-Wohnzimmer 35 Meldungen und Meinungen Lust auf Klassik? aus der Musikwelt 4 Da Capo: Gezischtes Doppel www.reservix.de Leserreise: der RONDO-Opernkritik 36 Menuhin-Festival Gstaad 5 6 Christiane Karg: Silberne Lieder 6 Christiane Karg: CDs, Bücher & Silberne Lieder Julia Fischer: Sammlerboxen Ein spanischer Strauß 8 RONDO-CD: Abonnenten Fauré Quartett: kriegen was auf die Ohren 38 Kammer-Orchester 10 Klassik-CDs Carl Philipp Emanuel: mit der „CD des Monats“ Der schwarze Bach 12 39 Artemis Quartett & Vokal total: Konzerte am Neuerscheinungen für Stimm- 8 Cuarteto Casals: -

Das Magazin Der Nordwestdeutschen Philharmonie

INFORMATIONEN.SPIELORTE.TERMINE MAI.JUNI.JULI.AUGUST 2019 S.1 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Musikfreunde, bevor die Musikerinnen und Musiker der NWD Anfang Juli in die wohlverdiente Sommerpause starten, haben die Menschen in Ostwestfalen- Lippe noch etliche Male Gelegenheit, das Orchester in Konzerten zu erleben. Auf eine schon beachtliche Tradition können wir mit der »Klassik zu Pfingsten« zurückblicken: Seit 2002 gibt es das Pfingstfestival der NWD. Vor 17 Jahren zunächst als »Begegnung mit Beethoven« begonnen, hat es sich längst zu einer festen und nachgefragten Größe im frühsommerlichen Kulturleben unserer Region entwickelt. Ich will an dieser Stelle noch nicht zu viel verraten, doch anlässlich des 250. Geburtstages Ludwig van Beethovens wird Ihnen die NWD im nächsten Jahr wieder musikalische Begegnungen mit diesem bedeutenden Komponisten ermöglichen. Mit der »Alpensinfonie« von Richard Strauss wagt sich das Orchester nach Pfingsten an das wohl gigantischste sinfonische Werk der Musikgeschichte. Dass es gelingt, für dieses bedeutende und selten zu hörende Werk über 100 Musiker auf die Bühne zu bringen, ist einer Kooperation mit dem Ural Youth Symphony Orchestra aus dem russischen Jekaterinburg zu verdanken. Mit einem weiteren Mammutvorhaben beginnt auch die neue Konzertsaison. Zweimal wird die NWD Richard Wagners Opern-Tetralogie »Der Ring des Nibelungen« als Gemeinschaftsproduktion mit dem Richard Wagner Verband Minden und dem Stadttheater Minden aufführen. Freuen Sie sich schon jetzt mit mir auf den glanzvollen Abschluss eines auf fünf Jahre angelegten Projektes, das höchsten künstlerischen Ansprüchen gerecht wird. Ihr Andreas Kuntze/Intendant Andreas Kuntze intermezzo DAS MAGAZIN DER NORDWESTDEUTSCHEN PHILHARMONIE TIEF VERWURZELT IN DER ARMENISCHEN VOLKSMUSIK WERKE VON ARAM KHACHATURIAN ERKLINGEN BEI DER »KLASSIK ZU PFINGSTEN« Aram Khachaturian (1903–1978) Zu seinem mitreißenden Rhythmus tanzte die junge Dessen Sinfonie Nr. -

Festival Verdi

INTERNO ALETTA TESTO GUTTUSO Personalità e genio ritratti con pochi segni di matita. Decisi. Sicuri. Delineano il volto inconfondibile, lo sguardo penetrante, l’espressione severa. Il ritratto di Giuseppe Verdi realizzato da Renato Guttuso negli anni ‘60, donato al Teatro Regio di Parma dall’Archivio storico Bocchi, in ricordo di Mario Bocchi, diviene, nell’anno del Bicentenario, icona originale, esclusiva, del Festival Verdi. FONDAZIONE Presidente Sindaco di Parma Federico Pizzarotti Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Giuseppe Albenzio Laura Maria Ferraris Silvio Grimaldeschi Marco Alberto Valenti Amministratore esecutivo Carlo Fontana Direttore artistico Paolo Arcà Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Andrea Frattini Alessandro Picinini Comitato promotore delle celebrazioni verdiane Presidente Paolo Peluffo Comitato di consulenza musicologica per il Festival Verdi Marcello Conati Gerardo Guccini Emilio Sala Il Festival Verdi è realizzato grazie al contributo di Major partner Partner eventi speciali Partner Main partner Sponsor Sponsor tecnici Tour operator partner Partner celebrazioni Il Teatro Regio di Parma ringrazia inoltre gli imprenditori che hanno voluto personalmente sostenere il Festival Verdi 2013 Teatro Regio di Parma 30 settembre 2013 FILARMONICA DELLA SCALA Direttore RICCARDO CHAILLY Musiche Giuseppe Verdi 1, 4, 6, 8, 11 ottobre 2013 SIMON BOCCANEGRA Musica Giuseppe Verdi 10 ottobre 2013 FILARMONICA ARTURO TOSCANINI CORO DEL TEATRO REGIO DI PARMA Direttore YURI TEMIRKANOV Musiche Giuseppe -

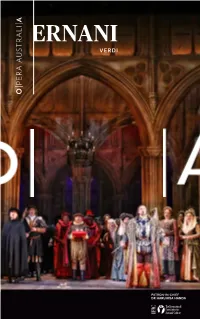

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

Premieren Der Oper Frankfurt Ab September 1945 Bis Heute

Premieren der Oper Frankfurt ab September 1945 bis heute Musikalische Leitung der Titel (Title) Komponist (Composer) Premiere (Conductor) Regie (Director) Premierendatum (Date) Spielzeit (Season) 1945/1946 Tosca Giacomo Puccini Ljubomir Romansky Walter Jokisch 29. September 1945 Das Land des Lächelns Franz Lehár Ljubomir Romansky Paul Kötter 3. Oktober 1945 Le nozze di Figaro W.A. Mozart Dr. Karl Schubert Dominik Hartmann 21. Oktober 1945 Wiener Blut Johann Strauß Horst-Dietrich Schoch Walter Jokisch 11. November 1945 Fidelio Ludwig van Beethoven Bruno Vondenhoff Walter Jokisch 9. Dezember 1945 Margarethe Charles Gounod Ljubomir Romansky Walter Jokisch 10. Januar 1946 Otto und Theophano Georg Friedrich Händel Bruno Vondenhoff Walter Jokisch 22. Februar 1946 Die Fledermaus Johann Strauß Ljubomir Romansky Paul Kötter 24. März 1946 Zar und Zimmermann Albert Lortzing Ljubomir Romansky Heinrich Altmann 12. Mai 1946 Jenufa Leoš Janáček Bruno Vondenhoff Heinrich Altmann 19. Juni 1946 Spielzeit 1946/1947 Ein Maskenball Giuseppe Verdi Bruno Vondenhoff Hans Strohbach 29. September 1946 Così fan tutte W.A. Mozart Bruno Vondenhoff Hans Strohbach 10. November 1946 Gräfin Mariza Emmerich Kálmán Georg Uhlig Heinrich Altmann 15. Dezember 1946 Hoffmanns Erzählungen Jacques Offenbach Werner Bitter Karl Puhlmann 2. Februar 1947 Die Geschichte vom Soldaten Igor Strawinsky Werner Bitter Walter Jokisch 30. April 1947 Mathis der Maler Paul Hindemith Bruno Vondenhoff Hans Strohbach 8. Mai 1947 Cavalleria rusticana / Pietro Mascagni / Werner Bitter Heinrich Altmann 1. Juni 1947 Der Bajazzo Ruggero Leoncavallo Spielzeit 1947/1948 Ariadne auf Naxos Richard Strauss Bruno Vondenhoff Hans Strohbach 12. September 1947 La Bohème Giacomo Puccini Werner Bitter Hanns Friederici 2. November 1947 Die Entführung aus dem W.A. -

Opera Australia 2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Cover image: Simon Lobelson as Gregor in Metamorphosis, which played at the Opera Australia Scenery Workshop in Enriching Australia’s Surry Hills and the Malthouse cultural life with Theatre in Melbourne. exceptional opera. One of Opera Australia’s new Vision productions, it was written by Australian Brian Howard, performed by an all Australian cast To present opera that excites and produced by an all Australian audiences and sustains and creative team. Photo: develops the art form. Prudence Upton Mission TABLE OF CONTENTS At a glance 3 Artistic Sydney Screens on stage 32 Director’s Report 12 Conservatorium Productions: of Music 2018 awards 34 performances and Regional Tour 13 Internships 23 attendances 4 China tour 36 Regional Student Professional and Artists 38 Season star ratings 5 Scholarships 16 Talent Development 24 Orchestra 39 Revenue and expenditure 6 Schools Tour 18 Evita 26 Philanthropy 40 Australia’s biggest Auslan Handa Opera arts employer 7 shadow-interpreting 20 on Sydney Harbour – Opera Australia Community reach 8 Community events 21 La Bohème 28 Capital Fund 43 Chairman’s Report 10 NSW Regional New works Staff 46 Conservatoriums in development 30 Partners 48 Chief Executive Project 22 Officer’s Report 11 opera.org.au 2 At a glance 77% Self-generated revenue $61mBox office 1351 jobs provided 543,500 58,000 attendees student attendees 7 637 productions new to Australia performances opera.org.au 3 Productions Productions Performances Attendance A Night at the Opera, Sydney 1 2,182 Performances and total attendances Aida, Sydney 19 26,266 By the Light of the Moon, Victorian Schools tour 85 17,706 Carmen, Sydney 13 18,536 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Melbourne 4 6,175 Don Quichotte, Melbourne 4 5,269 Don Quichotte, Sydney 6 7,889 Great Opera Hits 2018 27 23,664 La Bohème, Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour 26 48,267 La Bohème, Melbourne 7 11,228 La Bohème, New Year 1 1,458 The chorus of Bizet’s Carmen, directed by John Bell. -

Gaetano Donizetti

Gaetano Donizetti ORC 3 in association with Box cover : ‘ Eleonore, Queen of Portugal’ by Joos van Cleve, 1530 (akg-images/Erich Lessing) Booklet cover : The duel, a scene from Gioja’s ballet Gabriella di Vergy , La Scala, Milan, 1826 Opposite : Gaetano Donizetti CD faces: Elizabeth Vestris as Gabrielle de Vergy in Pierre de Belloy’s tragedy, Paris, 1818 –1– Gaetano Donizetti GABRIELLA DI VERGY Tragedia lirica in three acts Gabriella.............................................................................Ludmilla Andrew Fayel, Count of Vergy.......................................................Christian du Plessis Raoul de Coucy......................................................................Maurice Arthur Filippo II, King of France......................................................John Tomlinson Almeide, Fayel’s sister...................................................................Joan Davies Armando, a gentleman of the household...................................John Winfield Knights, nobles, ladies, servants, soldiers Geoffrey Mitchell Choir APPENDIX Scenes from Gabriella di Vergy (1826) Gabriella..............................................................................Eiddwen Harrhy Raoul de Coucy............................................................................Della Jones Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Conductor: Alun Francis –2– Managing director: Stephen Revell Producer: Patric Schmid Assistant conductor: David Parry Consultant musicologist: Robert Roberts Article and synopsis: Don White English libretto: -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

Wagnerkalender – Sluitingsdatum Van Deze Kalender 1 December 2017

Wagnerkalender – sluitingsdatum van deze kalender 1 december 2017 Amsterdam Tristan und Isolde, 18, 22, 25, 30 januari, 4, 7, 10 en 14 februari 2018 Pierre Audi regie, Christof Hetzer decor, Marc Albrecht dirigent, Stephen Gould (Tristan), Ricarda Merbeth (Isolde), Günther Groisböck (Marke), Ian Paterson (Kurwenal), Michelle Breedt (Brangäne), Roger Smeets (Ein Steuermann), Marc Lachner (Ein Hirt/Ein Junger Seemann) Tannhäuser light, 26 mei, Muziekgebouw aan het IJ Pocketversie van Tannhäuser, samengesteld door Carel Alphenaar. Michael Gieler dirigent, zangers: Laetitia Gerards, Gustavo Peña, Aylin Sezer, Michael Wilmering, orkest: leden van het Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest. Der Ring ohne Worte (arr. Lorin Maazel), Concertgebouw 13 juni 2018 UVA-orkest J.Pzn. Sweelinck Fragmenten uit de Ring, 20, 21 en 22 juni 2018, Concertgebouw Concertant, Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest o.l.v. Daniele Gatti, met medewerking van Eva-Maria Westbroek. Antwerpen Parsifal, 18, 21, 24, 27, 29 maart, 1 en 4 april 2018 Tatjana Gürbaca regie, Henrik Ahr decor, Cornelius Meister dirigent, Erin Caves (Parsifal), Tanja Ariane Baumgartner (Kundry), Stefan Kocan (Gurnemanz), Christoph Pohl (Amfortas), Károly Szemerédy (Klingsor), Markus Suihkonen (Titurel) Baden Baden - Festspielhaus Parsifal, 24 en 30 maart, 2 april 2018 Dieter Dorn regie, Magdalena Gut decor, Simon Rattle dirigent, Stephen Gould (Parsifal), Franz-Josef Selig (Gurnemanz), Ruxandra Donose (Kundry), Evgeny Nikitin (Klingsor), Gerald Finley (Amfortas) Der fliegende Holländer, 18 mei 2018 (concertant) -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2010 T 05 Stand: 19. Mai 2010 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin) 2010 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT05_2010-1 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence.