JOS-075-1-2018-007 Child Prodigy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Alberto Zedda

Le pubblicazioni del Rossini Opera Festival sono realizzate con il contributo di Amici del Friends of the Note al programma Rossini Opera Festival Rossini Opera Festival della XL Edizione Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica XL edizione 11~23 agosto 2019 L’edizione 2019 è dedicata a Montserrat Caballé e a Bruno Cagli MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI Regione Marche Enti fondatori Il Rossini Opera Festival si avvale della collaborazione scientifica della Fondazione Rossini Il Festival 2019 si attua con il contributo di Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Comune di Pesaro Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino Comune di Pesaro Regione Marche in collaborazione con Intesa Sanpaolo Fondazione Gruppo Credito Valtellinese Fondazione Scavolini con l’apporto di Abanet Internet Provider Bartorelli-Rivenditore autorizzato Rolex Eden Viaggi Grand Hotel Vittoria - Savoy Hotel - Alexander Museum Palace Hotel Harnold’s Hotel Excelsior Ratti Boutique Subito in auto Teamsystem Websolute partecipano AMAT-Associazione marchigiana attività teatrali AMI-Azienda per la mobilità integrata e trasporti ASPES Spa Azienda Ospedaliera San Salvatore Centro IAT-Informazione e accoglienza turistica Conservatorio di musica G. Rossini Si ringrazia UBI Banca per il contributo erogato tramite Art Bonus United Nations Designated Educational, Scientific and UNESCO Creative City Cultural Organization in 2017 Il Festival è membro di Italiafestival e di Opera Europa Sovrintendente Ernesto Palacio Direttore generale Olivier Descotes Presidente Relazioni -

Document (Pdf)

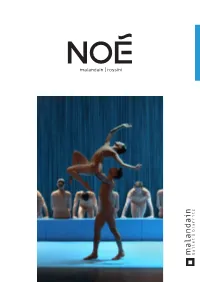

Creation / Basque Eurocity Teatro Victoria Eugenia - Donostia / San Sebastián NOAH Choreography Thierry Malandain Music Gioacchino Rossini - Messa di Gloria Set and costumes Jorge Gallardo Lighting design Francis Mannaert Dressmaker Véronique Murat Set production Frédéric Vadé Coproducers Chaillot - Théâtre National de la Danse(Paris), Opéra de Saint-Etienne, Donostia Kultura - Teatro Victoria Eugenia de Donostia / San Sebastián - Ballet T, CCN Malandain Ballet Biarritz. Partners Opéra de Reims, Théâtre de Gascogne - le Pôle, Theater Bonn (Allemagne), Forum am Schlosspark – Ludwigsburg (Allemagne) CREATION / BASQUE EUROCITY Teatro Victoria Eugenia de Donostia / San Sebastián, january 14th and 15th 2017 CREATION / FRENCH PREMIERE Chaillot - Théâtre National de la Danse (Paris) beetween May 10th and 24th 2017 Ballet for 22 dancers Lenght 70 minutes © Olivier Houeix Mickaël Conte et Irma Hoffren © Olivier Houeix NOAH CREATION 2017 Inspired by the parable of Noah’s Ark, Thierry Malandain’s new ballet once again addresses themes that he holds dear, such as Mankind and its future, destiny, fate, and the environment. From this story, which incidentally is rarely used in dance, he retains the symbolism rather than the religious message. Just as in the Biarritz choreographer’s previous work, Noah is punctuated with discreet references. For example, water, alternately destructive and life-sustaining, which is represented here as the element that gives new life to Mankind. Similarly, it represents the sacrament that we’re supposed to walk away from feeling different, if not changed. Mankind which boarded the Ark for forty days will emerge transformed. In essence, every artist dreams that the audience leaves a performance slightly changed. Malandain presents a more abstract Noah, who is not only a Christian reference to a new Adam, but also a figure common to various civilizations that lived through a flood and were saved by a protective, providential man. -

Donizetti Operas and Revisions

GAETANO DONIZETTI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Il Pigmalione (1816), libretto adapted from A. S. Sografi First performed: Believed not to have been performed until October 13, 1960 at Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. • L'ira d'Achille (1817), scenes from a libretto, possibly by Romani, originally done for an opera by Nicolini. First performed: Possibly at Bologna where he was studying. First modern performance in Bergamo, 1998. • Enrico di Borgogna (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: November 14, 1818 at Teatro San Luca, Venice. • Una follia (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: December 15, 1818 at Teatro San Luca,Venice. • Le nozze in villa (1819), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: During Carnival 1820-21 at Teatro Vecchio, Mantua. • Il falegname di Livonia (also known as Pietro, il grande, tsar delle Russie) (1819), libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini First performed: December 26, 1819 at the Teatro San Samuele, Venice. • Zoraida di Granata (1822), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: January 28, 1822 at the Teatro Argentina, Rome. • La zingara (1822), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: May 12, 1822 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. • La lettera anonima (1822), libretto by Giulio Genoino First performed: June 29, 1822 at the Teatro del Fondo, Naples. • Chiara e Serafina (also known as I pirati) (1822), libretto by Felice Romani First performed: October 26, 1822 at La Scala, Milan. • Alfredo il grande (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: July 2, 1823 at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples. • Il fortunate inganno (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: September 3, 1823 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. -

La Favorite Opéra De Gaetano Donizetti

La Favorite opéra de Gaetano Donizetti NOUVELLE PRODUCTION 7, 9, 12, 14, 19 février 2013 19h30 17 février 2013 17h Paolo Arrivabeni direction Valérie Nègre mise en scène Andrea Blum scénographie Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Alejandro Leroux lumières Sophie Tellier choréraphie Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Alice Coote, Celso Albelo, Ludovic Tézier, Service de presse Carlo Colombara, Loïc Félix, Judith Gauthier tél. 01 49 52 50 70 [email protected] Orchestre National de France Chœur de Radio France theatrechampselysees.fr Chœur du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Radio France La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la Réservations programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. 01 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr 5 Depuis quelques saisons, le bel canto La Favorite et tout particulièrement Donizetti ont naturellement trouvé leur place au Gaetano Donizetti Théâtre puisque pas moins de quatre des opéras du compositeur originaire Opéra en quatre actes (1840, version française) de Bergame ont été récemment Livret d’Alphonse Royer et Gustave Vaëz, d’après Les Amours malheureuses présentés : la trilogie qu’il a consacré ou Le Comte de Comminges de François-Thomas-Marie de Baculard d’Arnaud aux Reines de la cour Tudor (Maria Stuarda, Roberto Devereux et Anna Bolena) donnée en version de direction musicale Paolo Arrivabeni concert et, la saison dernière, Don Valérie Nègre mise en scène Pasquale dans une mise en scène de Andrea Blum scénographie Denis Podalydès. Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Compositeur prolifique, héritier de Rossini et précurseur de Verdi, Alejandro Le Roux lumières Donizetti appartient à cette lignée de chorégraphie Sophie Tellier musiciens italiens qui triomphèrent dans leur pays avant de conquérir Paris. -

Anna Bolena Opera by Gaetano Donizetti

ANNA BOLENA OPERA BY GAETANO DONIZETTI Presentation by George Kurti Plohn Anna Bolena, an opera in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, is recounting the tragedy of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of England's King Henry VIII. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style, meaning beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, prevalent during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was born in 1797 and died in 1848, at only 51 years of age, of syphilis for which he was institutionalized at the end of his life. Over the course of is short career, Donizetti was able to compose 70 operas. Anna Bolena is the second of four operas by Donizetti dealing with the Tudor period in English history, followed by Maria Stuarda (named for Mary, Queen of Scots), and Roberto Devereux (named for a putative lover of Queen Elizabeth I of England). The leading female characters of these three operas are often referred to as "the Three Donizetti Queens." Anna Bolena premiered in 1830 in Milan, to overwhelming success so much so that from then on, Donizetti's teacher addressed his former pupil as Maestro. The opera got a new impetus later at La Scala in 1957, thanks to a spectacular performance by 1 Maria Callas in the title role. Since then, it has been heard frequently, attracting such superstar sopranos as Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Montserrat Caballe. Anna Bolena is based on the historical episode of the fall from favor and death of England’s Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII. -

Roberto Devereux

GAETANO DONIZETTI roberto devereux conductor Opera in three acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano, production Sir David McVicar after François Ancelot’s tragedy Elisabeth d’Angleterre set designer Sir David McVicar Saturday, April 16, 2016 costume designer 1:00–3:50 PM Moritz Junge lighting designer New Production Paule Constable choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Roberto Devereux was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund The presentation of Donizetti’s three Tudor queen operas this season is made possible through a generous grant from Daisy Soros, general manager in memory of Paul Soros and Beverly Sills Peter Gelb music director James Levine Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera principal conductor Fabio Luisi and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées 2015–16 SEASON The seventh Metropolitan Opera performance of GAETANO DONIZETTI’S This performance roberto is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– devereux Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, conductor America’s luxury Maurizio Benini homebuilder®, with generous long-term in order of vocal appearance support from sar ah (sar a), duchess of not tingham The Annenberg Elīna Garanča Foundation, The Neubauer Family queen eliz abeth (elisabet ta) Foundation, the Sondra Radvanovsky* Vincent A. Stabile Endowment for lord cecil Broadcast Media, Brian Downen and contributions from listeners a page worldwide. Yohan Yi There is no sir walter (gualtiero) r aleigh Toll Brothers– Christopher Job Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall robert (roberto) devereux, e arl of esse x today. Matthew Polenzani This performance is duke of not tingham also being broadcast Mariusz Kwiecien* live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on a servant of not tingham SiriusXM channel 74. -

POLIUTO Salvadore Cammarano Adolphe Nourrit Gaetano Donizetti

POLIUTO Tragedia lirica. testi di Salvadore Cammarano Adolphe Nourrit musiche di Gaetano Donizetti Prima esecuzione: 30 novembre 1848, Napoli. www.librettidopera.it 1 / 32 Informazioni Poliuto Cara lettrice, caro lettore, il sito internet www.librettidopera.it è dedicato ai libretti d©opera in lingua italiana. Non c©è un intento filologico, troppo complesso per essere trattato con le mie risorse: vi è invece un intento divulgativo, la volontà di far conoscere i vari aspetti di una parte della nostra cultura. Motivazioni per scrivere note di ringraziamento non mancano. Contributi e suggerimenti sono giunti da ogni dove, vien da dire «dagli Appennini alle Ande». Tutto questo aiuto mi ha dato e mi sta dando entusiasmo per continuare a migliorare e ampliare gli orizzonti di quest©impresa. Ringrazio quindi: chi mi ha dato consigli su grafica e impostazione del sito, chi ha svolto le operazioni di aggiornamento sul portale, tutti coloro che mettono a disposizione testi e materiali che riguardano la lirica, chi ha donato tempo, chi mi ha prestato hardware, chi mette a disposizione software di qualità a prezzi più che contenuti. Infine ringrazio la mia famiglia, per il tempo rubatole e dedicato a questa attività. I titoli vengono scelti in base a una serie di criteri: disponibilità del materiale, data della prima rappresentazione, autori di testi e musiche, importanza del testo nella storia della lirica, difficoltà di reperimento. A questo punto viene ampliata la varietà del materiale, e la sua affidabilità, tramite acquisti, ricerche in biblioteca, su internet, donazione di materiali da parte di appassionati. Il materiale raccolto viene analizzato e messo a confronto: viene eseguita una trascrizione in formato elettronico. -

Il Turco in Italia

Rossini, G.: Adelaide di Borgogna 8.660401-02 http://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=8.660401-02 Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) Adelaide di Borgona Dramma per musica in due atti Libretto di Giovanni Schmidt Prima rappresentazione: Roma, Teatro Argentina, 27 dicembre 1817 New edition after the manuscripts by Florian Bauer for ROSSINI IN WILDBAD, Edition penso-pr Ottone: .......................................................................... Margarita Gritskova Adelaide: ................................................................. Ekaterina Sadovnikova Berengario: ............................................................ Baurzhan Anderzhanov Adelberto: ............................................................................ Gheorghe Vlad Eurice: .................................................................................. Miriam Zubieta Iroldo: ............................................................................. Yasushi Watanabe Ernesto:...................................................................... Cornelius Lewenberg La scena è parte nell’antica fortezza di Canosso presso il lago di Garda, e parte nel campo di Ottone. L’azione è nell’anno 947. CD 1 Berengario Pur cadeste in mio potere, suol nemico, infide mura; [1] Sinfonia lieto giorno, omai sicura la corona al crin mi sta. Atto primo Iroldo Interno della fortezza di Canosso, (Infelice! In tal cimento ingombra da macchine di guerra. più speranza, oh dio! non hai; »di salvarti invan tentai,« Scena prima né salvarti Otton potrà.) Il popolo -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Gli Esiliati in Siberia, Exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson

Gli esiliati in Siberia, exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson How many times did Donizetti write or rewrite Otto mesi in due ore. No one has ever been quite sure: at least five times, perhaps seven - it depends how the changes he made are viewed. Between 1827 and 1845 he set and reset the music of this strange but true tale of heroism - of the eighteen-year-old daughter who struggled through snow and ice for eight months to plead with the Tsar for the release of her father from exile in Siberia, making endless changes - giving it a handful of titles, six different poets supplying new verses (including the maestro himself), with- and-without spoken dialogue, with-and-without Neapolitan dialect, with-and-without any predictable casting (the prima donna could be a soprano, mezzo-soprano or contralto at will), and with-and-without any very enduring resolution at the end so that this extraordinary work has an even-more-fantastic choice of synopses than usual. It was this score that stayed with him throughout his years of international fame even when Lucia di Lammermoor and Don Pasquale were taking the world by storm. It is perfectly possible in fact that the music of his final revision of Otto mesi in due ore was the very last to which he turned his stumbling hand before mental collapse put an end to his hectic career. How did it come by its peculiar title? In 1806 Sophie Cottin published a memoir in London and Paris of a real-life Russian heroine which she called 'Elisabeth, ou Les Exilés de Sibérie'. -

|What to Expect from L'elisir D'amore

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM L’ELISIR D’AMORE AN ANCIENT LEGEND, A POTION OF QUESTIONABLE ORIGIN, AND THE WORK: a single tear: sometimes that’s all you need to live happily ever after. When L’ELISIR D’AMORE Gaetano Donizetti and Felice Romani—among the most famous Italian An opera in two acts, sung in Italian composers and librettists of their day, respectively—joined forces in 1832 Music by Gaetano Donizetti to adapt a French comic opera for the Italian stage, the result was nothing Libretto by Felice Romani short of magical. An effervescent mixture of tender young love, unforget- Based on the opera Le Philtre table characters, and some of the most delightful music ever written, L’Eli s ir (The Potion) by Eugène Scribe and d’Amore (The Elixir of Love) quickly became the most popular opera in Italy. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber Donizetti’s comic masterpiece arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in 1904, First performed May 12, 1832, at the and many of the world’s most famous musicians have since brought the opera Teatro alla Cannobiana, Milan, Italy to life on the Met’s stage. Today, Bartlett Sher’s vibrant production conjures the rustic Italian countryside within the opulence of the opera house, while PRODUCTION Catherine Zuber’s colorful costumes add a dash of zesty wit. Toss in a feisty Domingo Hindoyan, Conductor female lead, an earnest and lovesick young man, a military braggart, and an Bartlett Sher, Production ebullient charlatan, and the result is a delectable concoction of plot twists, Michael Yeargan, Set Designer sparkling humor, and exhilarating music that will make you laugh, cheer, Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer and maybe even fall in love.