Eliahu INBAL Conductor Laureate 桂冠指揮者 エリアフ・インバル

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubinstein Festival

ES THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL TWO RECITALS: JERUSALEM ■ TEL AVIV TWO SPECIAL CONCERTS: TEL AVIV CONDUCTOR: ELIAHU iNBAL September 1968 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ne Israel Philharmonic Orchestra again a galley slave,” Rubinstein answered : returned each year since then to triumph as the pleasure and profound honour to "Excuse me, Madame,a galley slave is ant successes. welcome the illustrious Pianist, ARTUR condemned to work he detests, but I am RUBINSTEIN, whose artistry has brought in love with mine; madly in love. It isn’t Rubinstein married the beautiful Aniela enjoyment and spiritual fulfillment to many work, it is passion and always pleasurable. Mlynarski, daughter of conductor Emil thousands of music lovers in our country, I give an average of a hundred concerts Mlynarski under whose baton he had to yet another RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL. The a year. One particular year, I toted up one played in Warsaw when he was 14. Four great virtuoso, whose outstanding inter hundred and sixty-two on four continents. children were born to the Rubinsteins, pretation is so highly revered, has retained That, I am sure, is what keeps me young.” two boys and two girls. the spontaneity of youthfulness despite the Artur Rubinstein was born in Warsaw, the In 1954 Rubinstein acquired his home in passing of time. youngest of seven children. His remark Paris, near the house in which Debussy able musical gifts revealed themselves spent the last 13 years of his life, by the Artur Rubinstein could now be enjoying Bois de Boulogne. It is there that he now the ease and comforts of ‘‘The Elder very early and at the age of eight, after receiving serious encouragement from lives in between the tours that take him Statesman”, with curtailed commitments all round the world. -

Martinu° Classics Cello Concertos Cello Concertino

martinu° Classics cello concertos cello concertino raphael wallfisch cello czech philharmonic orchestra jirˇí beˇlohlávek CHAN 10547 X Bohuslav Martinů in Paris, 1925 Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Concerto No. 1, H 196 (1930; revised 1939 and 1955)* 26:08 for Cello and Orchestra 1 I Allegro moderato 8:46 2 II Andante moderato 10:20 3 III Allegro – Andantino – Tempo I 7:00 Concerto No. 2, H 304 (1944 – 45)† 36:07 © P.B. Martinů/Lebrecht© P.B. Music & Arts Photo Library for Cello and Orchestra 4 I Moderato 13:05 5 II Andante poco moderato 14:10 6 III Allegro 8:44 7 Concertino, H 143 (1924)† 13:54 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur for Cello, Wind Instruments, Piano and Percussion Allegro TT 76:27 Raphael Wallfisch cello Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Bohumil Kotmel* • Josef Kroft† leaders Jiří Bělohlávek 3 Miloš Šafránek, in a letter that year: ‘My of great beauty and sense of peace. Either Martinů: head wasn’t in order when I re-scored it side lies a boldly angular opening movement, Cello Concertos/Concertino (originally) under too trying circumstances’ and a frenetically energetic finale with a (war clouds were gathering over Europe). He contrasting lyrical central Andantino. Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra had become reasonably well established in set about producing a third version of his Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific writer of Paris and grown far more confident about his Cello Concerto No. 1, removing both tuba and Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra concertos and concertante works. Among own creative abilities; he was also receiving piano from the orchestra but still keeping its In 1941 Martinů left Paris for New York, just these are four for solo cello, and four in which much moral support from many French otherwise larger format: ahead of the Nazi occupation. -

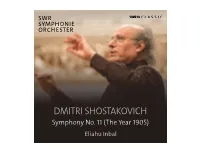

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No

SWR SYMPHONIE ORCHESTER DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 11 (The Year 1905) Eliahu Inbal Mit Kamerablick (1906–1975) DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Mit dem Tod Stalins 1953 begann in der Sowjet- Die jüngere russische Geschichte war schon Sinfonie Nr. 11 g-Moll op. 103 (Das Jahr 1905) union eine neue Periode, die vorsichtige vorher oft ein Thema in Schostakowitschs Symphony No.11 in G Minor Op.103 (The Year 1905) Hoffnung auf eine Verbesserung des innen- sinfonischem Schaffen – man denke an seine politischen Klimas weckte. Für den jahrelang 7. Sinfonie, die „Leningrader“ (1942). In dieser 1 I Der Platz vor dem Palast. Adagio 13:32 drangsalierten und gedemütigten Komponis- Zeit des Aufbruchs war ihm eine Erinnerung an The Palace Square. Adagio ten Dmitri Schostakowitsch bedeutete sie die Wurzeln der Sowjetunion ein besonderes jedenfalls eine Erleichterung seiner Arbeit. Anliegen. In den ersten Jahren des 20. Jahr- 2 II Der neunte Januar. Allegro 18:09 Gemaßregelte frühere Werke durften wieder hunderts hatte sich die schon vorher missliche The 9th of January. Allegro gespielt werden, für neue gab es günstigere Lage der Arbeiter in Russland dramatisch ver- 3 III Ewiges Gedenken. Adagio 11:08 Startbedingungen. Das setzte bei ihm neue schlechtert, die Unterdrückung durch Landbe- In memoriam. Adagio schöpferische Energien frei. Die noch im sel- sitzer und Fabrikanten nahm immer brutalere 4 IV Sturmläuten. Allegro non troppo 15:26 ben Jahr fertig gestellte 10. Sinfonie wurde zur Formen an. Tocsin. Allegro non troppo Abrechnung mit dem Diktator, die zwar Dis- kussionen auslöste, aber überwiegend auf Zu- Am 22. Januar 1905 kam es zu einem General- stimmung stieß. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2005-2006 SEASON JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE filg ft . Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and' this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the -'^S^S- from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. LONGYEAB. a / C7isner Jrfill BROOKLINE www.longyearestates.com G*-' * ituunti : -•«*-- CORT-LAND I Hammond PROPERTIES INC. hH •2}••;•-'.h*. r.v^.t.irtv, *P"> K '£- •--' ^ • ^ The path to recovery...W ^McLean Hospital *5j ^Tlje nation's top psychiatric hospital. U.S. News & World Report^ M^H|^? *** v \ >/-*x ">r i K *i 1^. N' '1 ' yri ^ pStttil:: The Pavilion at McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment > j* ? ^Unsurpassed discretion and service Belmont, Massachusetts 617/855-3535 www.mclean.harvarcl.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERS™ of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital H E ALTHC i and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump I bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. -

„Es Gibt, Von Beethoven Angefangen, Keine Moder- Ne Musik, Die Nicht Ihr Inneres Programm Hat

Abonnement C, 6. Konzert Freitag 07.06.2019 · 20.00 Uhr Sonnabend 08.06.2019 · 20.00 Uhr Sonntag 09.06.2019 · 16.00 Uhr Großer Saal KONZERTHAUSORCHESTER BERLIN ELIAHU INBAL Dirigent FRANCESCO PIEMONTESI Klavier „Es gibt, von Beethoven angefangen, keine moder- ne Musik, die nicht ihr inneres Programm hat ... Man muss eben Ohren und ein Herz mitbringen …“ GUSTAV MAHLER AN MAX KALBECK, NOVEMBER 1900 PROGRAMM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) Konzert für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 2 B-Dur op. 19 ALLEGRO CON BRIO ADAGIO RONDO. MOLTO ALLEGRO PAUSE Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) Sinfonie Nr. 1 D-Dur LANGSAM. SCHLEPPEND KRÄFTIG BEWEGT, DOCH NICHT ZU SCHNELL FEIERLICH UND GEMESSEN, OHNE ZU SCHLEPPEN STÜRMISCH BEWEGT PREMIUMPARTNER Mobiltelefon ausgeschaltet? Vielen Dank! Cell phone turned off? Thank you! Wir machen darauf aufmerksam, dass Ton- und / oder Bildaufnahmen unserer Auf- führungen durch jede Art elektronischer Geräte strikt untersagt sind. Zuwiderhand- lungen sind nach dem Urheberrechtsgesetz strafbar. Beethoven: B-Dur-Klavierkonzert ENTSTEHUNG 1787/90 (1. Version), weitere Versionen 1793, 1794/95, 1798 und 1801 · URAUF- FÜHRUNG wahrscheinlich 29.3.1795 (3. Version; Ludwig van Beethoven, Leitung und Solist) BESETZUNG Solo-Klavier, Flöte, 2 Oboen, 2 Fagotte, 2 Hörner, Streicher · DAUER ca. 30 Minu- ten Beethovens zweites Klavierkonzert ist eigentlich sein erstes, denn sei- ne verwickelte Entstehung reicht bis in die späten 1780er Jahre zu- rück. Es gab mindestens vier ver- schiedene Werk-Versionen – auch mit einem Schlusssatz, der später wieder ausgeschieden wurde. Die endgültige Version stammt aus dem Jahr 1801, als das Werk zu- sammen mit dem – nunmehr – ersten Konzert in C-Dur im Druck der Stimmen erschien. -

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (Not Commercially Available As Recordings) Compiled by John F

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (not commercially available as recordings) Compiled by John F. Berky – June 3, 2020 (Updated May 20, 2021) 1910 /11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Wiener Konzertverein Orchester 1] 25.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 1] 24.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Graz) 2] 02.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 20.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 29.04.11 - Martin Spoerr (Bamberg) 3] 25.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 26.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 08.01.11 - Gustav Gutheil 3] 26.01.11- Ferdinand Loewe (Zagreb) 3] 17.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Budapest) 4] 07.01.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 12.02.11 - Martin Spoerr 4] 18.02.11 - Hans Maria Wellner 4] 26.02.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 02.03.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 23.04.11 - Franz Schalk 5] 05.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 21.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 03.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 17.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 02.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 23.02.11 - Oskar Nedbal 8] 12.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 9] 24.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 1910/11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Munich Philharmonic 1] 17.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 2] 14.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 21.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1890) 4] 09.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1889) 5] 30.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 13.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 27.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 06.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Psalm 150 -Charles Cahier) 9] 10.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Te Deum) 1919/20 – Arthur Nikisch – Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra 1] 09.10.19 - Artur Nikisch (1. -

Rudolfinum a Jeho Genius Loci

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Management v kultuře Magisterská diplomová práce Rudolfinum a jeho genius loci Bc. Veronika Hladká Vedoucí práce: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Brno 2010 1 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem pracovala samostatně a pouţila jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. 2 Poděkování: Děkuji svému vedoucímu práce Ing. Františkovi Svobodovi, Ph.D. za cenné rady a podnětné připomínky a za ochotu při spolupráci. 3 Obsah: Předmluva ………………………………………………………………………………... 6 Úvod ……………………………………………………………………………………... 7 Historie místa ……………………………………………………………………………. 9 1. Dům umělců Rudolfinum …………………………………………………………… 11 1.1. Vznik a historie budovy Rudolfinum…………………………………………. 12 1.2. Architektura Rudolfina včetně interiéru ………………………………………14 1.2.1. Úpravy a rekonstrukce ………………………………………………. 19 1.3. Sochařská výzdoba exteriéru …………………………………………………. 21 2. Rudolfinum jako kulturní stánek a jeho nejvýznamnější kulturní instituce…………. 25 2.1. Umělecké instituce v galerijních prostorách do roku 1929 …….…….…….. 26 2.1.1. Obrazárna Společnosti vlasteneckých přátel umění v Čechách …...... 26 2.1.2. Krasoumné jednota pro Čechy……………………………………… 31 2.2. Česká filharmonie …………………………………………………………… 34 2.2.1. Zrod České filharmonie a její činnost do roku 1945………………… 34 2.2.2. Od Praţského jara k Sametové revoluci…………………………….. 41 3. Renesance původní myšlenky dualismu ……………………………………………. 45 3.1. Galerie Rudolfinum …………………………………………………………. 46 3.2. Česká filharmonie v 90. letech 20. století aţ do současnosti ……………….. 50 4. Původní poslání dualismu -

Beethoven 1 Violin Concerto Symphonyno.8 Brahms String Sextet N O

BEETHOVEN 1 VIOLIN CONCERTO SYMPHONYNO.8 BRAHMS STRING SEXTET N O. l Augustin Dumay violin & conductor Ludwig van Beethoven 1770–1827 Violin Concerto in D op.61 * Violinkonzert D-dur / Concerto pour violon en ré majeur 1 I Allegro ma non troppo 24.54 2 II Larghetto 9.29 3 III Rondo : Allegro 10.08 Symphony no. 8 in F op.93 ** Sinfonie Nr. 8 F-dur / Symphonie n° 8 en fa majeur 4 I Allegro vivace e con brio 8.47 5 II Allegretto scherzando 3.52 6 III Tempo di minuetto 4.37 7 IV Allegro vivace 7.18 Augustin Dumay, violin & conductor * Sinfonia Varsovia ** Kansai Philharmonic Orchestra 1833–1897 Johannes Brahms 3 String Sextet no. 1 in B flat op.18 Streichsextett Nr. 1 B-dur / Sextuor à cordes n° 1 en si bémol majeur 8 I Allegro ma non troppo 15.01 9 II Andante ma moderato 9.17 10 III Scherzo : Allegro molto 2.47 11 IV Rondo : Poco allegretto e grazioso 10.03 Augustin Dumay, violin / Violine / violon Svetlin Roussev, violin / Violine / violon Miguel da Silva, viola / Bratsche / alto Marie Chilemme, viola / Bratsche / alto Henri Demarquette, cello / Cello / violoncelle Aurélien Pascal, cello / Cello / violoncelle Introduction This album presents three aspects of Augustin Dumay’s musical career : as soloist, 4 conductor and chamber musician. Augustin Dumay made his conducting debut at the age of 29, under the aegis of Herbert von Karajan, who had said to him ‘You can’t have as comprehensive an understanding of music as you do without conducting one day !’ Over the last ten years, Dumay has been increasingly in demand as a conductor, alongside his career as a violinist. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 25 June 2017 7pm Barbican Hall London’s Symphony Orchestra MAHLER SYMPHONY NO 3 Robert Trevino conductor Anna Larsson alto Tiffin Boys’ Choir Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey chorus director Please note that there will be no interval Concert finishes approx 8.50pm 2 Welcome 25 June 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at the NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR Barbican. We are joined by Robert Trevino, making EARLY-CAREER COMPOSERS his debut with the Orchestra. One of the most dynamic young American conductors to emerge Applications have re-opened for our flagship composer in recent years, Robert Trevino has a particularly programme – LSO Soundhub – which provides a strong reputation for Mahler. We are very grateful flexible environment for four composers annually to him for stepping in to replace Daniel Harding, to develop their work with access to vital resources, who is unable to conduct owing to a wrist injury. state-of-the-art equipment and professional support. We are very grateful to Susie Thomson for generously Tonight’s programme is focused on Mahler’s supporting LSO Soundhub from September 2017. expansive Third Symphony, for which we are delighted to welcome soloist Anna Larsson, The LSO is also launching a new programme, LSO the Tiffin Boys’ Choir, the London Symphony Jerwood Composer+, with the generous support of Chorus and our Choral Director Simon Halsey. the Jerwood Charitable Foundation. The programme will support two composers in programming and I hope you enjoy the concert and that you will delivering chamber-scale concerts at LSO St Luke’s, be able to join us again soon. -

Bruckner Journal V3 3.Pdf

Bruckner ~ Journal Issued three times a year and sold by subscription Editorial and advertising: telephone 0115 928 8300 2 Rivergreen Close, Beeston, GB-Nottingham NG9 3ES Subscriptions and mailing: telephone 01384 566 383 4 Lulworth Close, Halesowen, West Midlands B63 2UJ VOLUME THREE, NUMBER THREE, NOVEMBER 1999 Editor: Peter Palmer Managing Editor: Raymond Cox Associate Editor: Crawford Howie In This Issue WORDS AND MUSIC page Concerts 2 Care is taken to ensure that this publication is Matthias Bamert 6 as informative as possible. One of our Scandinavian subscribers was so kind as to say Compact Discs 7 that he read every word. But we are under no Viewpoint 14 illusions that our words are more than a substitute for great music. Rather, what has Book: Celibidache 16 pleased the journal's producers most is the Scores 17 growing network of contacts it has helped to bring about between Bruckner lovers many miles Reflections apart. What's more, music is a performing art, by Raymond Cox 19 and interpretative questions offer rich food for Bruckner's Songs thought and discussion. Surely it is upon by Angela Pachovsky 22 thoughtful, informed debate that the future appreciation of Bruckner depends. Bruckner Letters II by Crawford Howie 26 Some recent events in the publishing world have given more power to our elbow. The Anton Feedback 34 Bruckner Complete Edition (Gesamtausgabe) is now Calendar 36 entering its final stages. Although we operate independently of the International Bruckner Society, we take the view that this Edition is Contributors: the next of immense importance. That does not, however, deadline is 15 January. -

Masterclass Programme 2020

1 Class of 2019 ABOUT Hellensmusic is a music festival that takes place every May in and around Hellens Manor, Herefordshire. Its aims are threefold: to create opportunities for world-class musicians to collaborate outside the concert circuit and explore new ideas; to provide a platform for talented music students from all over the UK and beyond to learn from leading experts; and to bring great music to this corner of England, inspiring local audiences. Hellensmusic Masterclass Programme consists of six days of intense learning, with individual masterclasses, chamber music classes and music improvisation sessions taught by the Festival’s resident artists. The course culminates in two final concerts where students will have the opportunity to perform some of the pieces they worked on during the week and play alongside their tutors in chamber music ensembles. Our aim is to create a rich and inspiring musical week that can fast-track meaningful learning. We create a welcoming environment where everyone is warmly encouraged to explore, be curious and enjoy music to the fullest. Beyond the masterclasses, students have the chance to engage with their tutors at meals and breaks and can see them in action at rehearsals and performances. This provides a unique opportunity for informal learning, which sets Hellensmusic apart from other short courses. “An invaluable experience. I feel I gained so much knowledge from the tutors and learnt so much in such a short time. It has been a wonderful, encouraging environment in which to learn” THE TEAM We are proud to have a team of resident artists who are not only acclaimed performers but also committed and passionate teachers.