Bruckner Journal V3 3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubinstein Festival

ES THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL TWO RECITALS: JERUSALEM ■ TEL AVIV TWO SPECIAL CONCERTS: TEL AVIV CONDUCTOR: ELIAHU iNBAL September 1968 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ne Israel Philharmonic Orchestra again a galley slave,” Rubinstein answered : returned each year since then to triumph as the pleasure and profound honour to "Excuse me, Madame,a galley slave is ant successes. welcome the illustrious Pianist, ARTUR condemned to work he detests, but I am RUBINSTEIN, whose artistry has brought in love with mine; madly in love. It isn’t Rubinstein married the beautiful Aniela enjoyment and spiritual fulfillment to many work, it is passion and always pleasurable. Mlynarski, daughter of conductor Emil thousands of music lovers in our country, I give an average of a hundred concerts Mlynarski under whose baton he had to yet another RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL. The a year. One particular year, I toted up one played in Warsaw when he was 14. Four great virtuoso, whose outstanding inter hundred and sixty-two on four continents. children were born to the Rubinsteins, pretation is so highly revered, has retained That, I am sure, is what keeps me young.” two boys and two girls. the spontaneity of youthfulness despite the Artur Rubinstein was born in Warsaw, the In 1954 Rubinstein acquired his home in passing of time. youngest of seven children. His remark Paris, near the house in which Debussy able musical gifts revealed themselves spent the last 13 years of his life, by the Artur Rubinstein could now be enjoying Bois de Boulogne. It is there that he now the ease and comforts of ‘‘The Elder very early and at the age of eight, after receiving serious encouragement from lives in between the tours that take him Statesman”, with curtailed commitments all round the world. -

Martinu° Classics Cello Concertos Cello Concertino

martinu° Classics cello concertos cello concertino raphael wallfisch cello czech philharmonic orchestra jirˇí beˇlohlávek CHAN 10547 X Bohuslav Martinů in Paris, 1925 Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Concerto No. 1, H 196 (1930; revised 1939 and 1955)* 26:08 for Cello and Orchestra 1 I Allegro moderato 8:46 2 II Andante moderato 10:20 3 III Allegro – Andantino – Tempo I 7:00 Concerto No. 2, H 304 (1944 – 45)† 36:07 © P.B. Martinů/Lebrecht© P.B. Music & Arts Photo Library for Cello and Orchestra 4 I Moderato 13:05 5 II Andante poco moderato 14:10 6 III Allegro 8:44 7 Concertino, H 143 (1924)† 13:54 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur for Cello, Wind Instruments, Piano and Percussion Allegro TT 76:27 Raphael Wallfisch cello Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Bohumil Kotmel* • Josef Kroft† leaders Jiří Bělohlávek 3 Miloš Šafránek, in a letter that year: ‘My of great beauty and sense of peace. Either Martinů: head wasn’t in order when I re-scored it side lies a boldly angular opening movement, Cello Concertos/Concertino (originally) under too trying circumstances’ and a frenetically energetic finale with a (war clouds were gathering over Europe). He contrasting lyrical central Andantino. Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra had become reasonably well established in set about producing a third version of his Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific writer of Paris and grown far more confident about his Cello Concerto No. 1, removing both tuba and Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra concertos and concertante works. Among own creative abilities; he was also receiving piano from the orchestra but still keeping its In 1941 Martinů left Paris for New York, just these are four for solo cello, and four in which much moral support from many French otherwise larger format: ahead of the Nazi occupation. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1974, Tanglewood

Artistic Directors SEIII OZAWA Berkshire Festival GUNTHER SCHILLER Berkshire Music Center LEONARD BERNSTEIN Adviser Ian ewood 1974 BERKSHIRE FESTIVAL ' » I. \ 3£ tA fi!tWtJ-3mA~%^-u my*9^V r 1 t '," ' r ' ' T nfii , rum'*' / -'^ ])Jiit»~ }fil<'fj>it >'W BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director 3 ***** M , * <• v * > •« 3H a place to think An established, planned community designed to preserve the ecostruc- ture of the original forest-dirt roads, hiking paths, lakes and ponds, clean air, 4 to 6 acres all by yourself, neigh- boring on a 15,000 acre forest. Strong protective covenants. Restricted to 180 lots. ' J RECENT RECORD RELEASES BY THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA conducted by SEIJI OZAWA BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique DG/2530 358 THE GREAT STRAVINSKY BALLETS album includes Petrushka and Suite from The firebird RCA VCS 7099 i ) conducted by EUGEN JOCHUM MOZART & SCHUBERT (October release) Symphony no. 41 in C K. 551 'Jupiter' Symphony no. 8 in B minor 'Unfinished' DG/2530 357 conducted by WILLIAM STEINBERG HINDEMITH Symphony 'Mathis der Maler' ) DG/2530 246 Concert music for strings and brass S conducted by MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS \ STRAVINSKY Le sacre du printemps Le roi d'etoiles DG/2530 252 conducted by CHARLES MUNCH THE WORLD'S FAVORITE CONCERTOS album includes Mendelssohn's Violin concerto with Jascha Heifetz RCA LSC 3304 THE WORLD'S FAVORITE CONCERTOS album includes Beethoven's Violin concerto with Jascha Heifetz RCA LSC 3317 conducted by ERICH LEINSDORF V THE WORLD'S FAVORITE CONCERTOS album includes Tchaikovsky's Piano concerto no. 1 with Artur Rubinstein RCA LSC 3305 conducted by ARTHUR FIEDLER THE WORLD'S FAVORITE SYMPHONIES album includes the 'New World' symphony of Dvorak RCA LSC 3315 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ON and DUCBZJD Variations on a Theme by Palaset. -

Download Booklet

Matthias Bamert HALLOWEEN CLASSICS COMPACT DISC ONE Sortilege and Spook Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (1839 – 1881) 1 A Night on the Bare Mountain 10:15 Arranged by Leopold Stokowski (1882 – 1977) BBC Philharmonic Matthias Bamert Recording venue: Studio 7, New Broadcasting House, Manchester Recording date: June 1995 Sound engineer: Don Hartridge (CHAN 9445 – track 1) 3 Paul Dukas (1865 – 1935) 2 L’Apprenti sorcier 11:32 Symphonic Scherzo after Goethe Ulster Orchestra Yan Pascal Tortelier Recording venue: Ulster Hall, Belfast Recording date: 1989 Sound engineer: Ralph Couzens (CHAN 8852 – track 3) Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971) 3 Introduction – 3:16 4 Le Jardin enchanté de Kastchei 2:24 Two movements from L’Oiseau de feu Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra Dmitri Kitajenko Recording venue: Danish Radio Concert Hall, Copenhagen, Denmark Recording date: January 1991 Sound engineer: Lars S. Christensen (CHAN 8967 – tracks 2 and 3) 4 Courtesy of Iceland Symphony Orchestra Yan Pascal Tortelier Marco Borggreve Vassily Sinaisky Camille Saint-Saëns (1835 – 1921) 5 Danse macabre, Op. 40 6:38 Poème symphonique Royal Scottish National Orchestra Neeme Järvi Recording venue: Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow Recording date: September 2011 Sound engineer: Ralph Couzens (CHSA 5104 – track 4) Anatol Konstantinovich Lyadov (1855 – 1914) 6 The Enchanted Lake, Op. 62 7:40 Fairy-tale Picture BBC Philharmonic Vassily Sinaisky Recording venue: Studio 7, New Broadcasting House, Manchester Recording date: April 2000 Sound engineer: Stephen Rinker (CHAN 9911 – track 4) 7 Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891 – 1953) 7 The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father 3:21 No. 1 from incidental music to Hamlet, Op. 77 Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valeri Polyansky Recording venue: Grand Hall, Moscow Conservatory, Russia Recording date: April 2002 Sound engineer: Igor Verprintsev (CHAN 10056 – track 3) Sir Malcolm Arnold (1921 – 2006) 8 Tam o’ Shanter, Op. -

Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg

BLÄSERPHILHARMONIE MOZARTEUM SALZBURG DANY BONVIN GALACTIC BRASS GIOVANNI GABRIELI ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER RICHARD STRAUSS ANTON BRUCKNER WERNER PIRCHNER CD 1 WILLIAM BYRD (1543–1623) (17) Station XIII: Jesus wird vom Kreuz GALAKTISCHE MUSIK gewesen ist. In demselben ausgehenden (1) The Earl of Oxford`s March (3'35) genommen (2‘02) 16. Jahrhundert lebte und wirkte im Italien (18) Station XIV: Jesus wird ins „Galactic Brass“ – der Titel dieses Pro der Renaissance Maestro Giovanni Gabrieli GIOVANNI GABRIELI (1557–1612) Grab gelegt (1‘16) gramms könnte dazu verleiten, an „Star im Markusdom zu Venedig. Auf den einander (2) Canzon Septimi Toni a 8 (3‘19) Orgel: Bettina Leitner Wars“, „The Planets“ und ähnliche Musik gegenüber liegenden Emporen des Doms (3) Sonata Nr. XIII aus der Sterne zu denken. Er meint jedoch experimentierte Gabrieli mit Ensembles, „Canzone e Sonate” (2‘58) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACh (1685–1750) Kom ponisten und Musik, die gleichsam ins die abwechselnd mit und gegeneinander (19) Passacaglia für Orgel cMoll, BWV 582 ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER (*1943) Universum der Zeitlosigkeit aufgestiegen musizierten. Damit war die Mehrchörigkeit in der Fassung für acht Posaunen sind, Stücke, die zum kulturellen Erbe des gefunden, die Orchestermusik des Barock Via Crucis – Übermalungen nach den XIV von Donald Hunsberger (6‘15) Stationen des Kreuzweges von Franz Liszt Planeten Erde gehören. eingeleitet und ganz nebenbei so etwas für Orgel, Pauken und zwölf Blechbläser, RICHARD STRAUSS (1864–1949) wie natürliches Stereo. Die Besetzung mit Uraufführung (20) Feierlicher Einzug der Ritter des William Byrd, der berühmteste Komponist verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten war flexibel JohanniterOrdens, AV 103 (6‘40) Englands in der Zeit William Shakespeares, und wurde den jeweiligen Räumen ange (4) Hymnus „Vexilla regis“ (1‘12) hat einen Marsch für jenen Earl of Oxford passt. -

“Pulling out All the Stops” Psalm 150 Central Christian Church David A

May 16, 2021 “Pulling Out All the Stops” Psalm 150 Central Christian Church David A. Shirey Psalm 150 pulls out all the stops. I’m going to have Elizabeth read it. But before she does, I want to note a few things about this last and grandest Psalm. For instance, it’s an eight exclamation mark Psalm. Eight exclamation marks in six verses! My seventh grade English teacher, Mrs. Booth, would have said something about the overuse of that punctuation mark. If everything is an exclamation mark, then all you’re doing is shouting, the grammatical equivalent of ALL CAPS in an email or text. Nonetheless, Psalm 150 has eight exclamation marks. And the word praise thirteen times. Mrs. Booth would have suggested using synonyms rather than the same word. Acclaim. Extol. Worship. Glorify. Laud. Honor. Adore. Revere. But nonetheless, the word is praise... thirteen times. And to accompany the word praise thirteen times with eight exclamation marks the Psalmist strikes up the band, includes every instrument in the ancient orchestra: Trumpet. Lute. Harp. Tambourine. Strings. Pipe. Clanging Cymbals. Loud clashing cymbals. If you’re going to pull out all the stops, then them pull them out. Every instrument. Fortissimo. And if every instrument playing praise followed by eight exclamation marks is not enough, the Psalmist adds, “Dance.” “Praise God with tambourine and dance.” When you’re in the presence of the Living God in the holy sanctuary you can’t just sit there, hands folded, blank stare, body settling into rigor mortis. The Psalmist shouts, “Shall we dance?” Well, have I set the stage? Whetted your appetite for what to listen for in Psalm 150? 8 exclamation marks. -

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - Mehr Als ›Der Wohlbekannte Sänger‹

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - mehr als ›der wohlbekannte Sänger‹ Gottfried Kraus (Minihof-Liebau) In seiner persönlich gehaltenen Erinnerung sucht der Musikpublizist Gottfried Kraus die komplexe Persönlichkeit und vielfältige Lebensleistung Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus in großen Zügen darzustellen. Von der ersten Erinnerung des 15jährigen Konzertbesuchers an ein Brahms-Requiem unter Furtwängler im Wiener Konzerthaus und an Fischer-Dieskaus erste Winterreise im Januar 1951 spannt sich der Bogen über Eindrücke in Konzert und Oper und die umfassende Beschäftigung mit Fischer-Dieskaus Schallplattenaufnahmen bis zu gemeinsamer Arbeit. Als Leiter der Musikabteilung des Österreichischen Rundfunks lud Kraus den Sänger und Dirigenten Fischer-Dieskau zu Aufgaben im Studio und bei den Salzburger Festspielen. Auch für Schallplattenaufnahmen ergaben sich spätere Kontakte. Aus vielfältiger Erfahrung und nicht zuletzt auch aus freundschaftlicher Nähe zeichnet Kraus ein Bild Fischer-Dieskaus, der mehr ist und auch mehr sein will als nur ‚der wohlbekannte Sänger‘ – ein Künstler von unglaublicher Breite, den umfassende Bildung, das Bewusstsein großer Tradition, lebenslange Neugierde, Offenheit und enormer Fleiß dazu befähigten, auch als Rezitator, Dirigent, Musikschriftsteller und Maler Ungewöhnliches zu leisten. In his personally touched memoires the music publisher Gottfried Kraus tries to present the complex personality of Fischer-Dieskau and the miscellaneous achievements in his life along general lines. Starting with the fist remembrance of the 15-year-old concert visitor of a Brahms-Requiem conducted by Furtwängler at the Wiener Konzerthaus and the first Winterreise of Fischer-Dieskau in January 1951 he encompasses impressions of concerts and operas as well as the comprehensive engagement with disc records of Fischer-Dieskau up to their common work. As the head of the music department of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation, Kraus invited the singer and conductor Fischer-Dieskau for recordings in the studio and to the Salzburg Festival. -

Metamorphosis a Pedagocial Phenomenology of Music, Ethics and Philosophy

METAMORPHOSIS A PEDAGOCIAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF MUSIC, ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY by Catalin Ursu Masters in Music Composition, Conducting and Music Education, Bucharest Conservatory of Music, Romania, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education © Catalin Ursu 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall, 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

NEUE ANTON BRUCKNER GESAMTAUSGABE NEW ANTON BRUCKNER COMPLETE EDITION Das Projekt the Project

12. Fahne 08.02.16 SYMPHONIE NR. 1 IN C-MOLL Linzer Fassung 1. SATZ Anton Bruckner Allegro Flöte 1. 2. b & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe 1. 2. b & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Einladung zur Subskription / Invitation to subscribe Klarinette 1. 2. in B & b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Fagott 1. 2. ? b b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ NEUE ANTON BRUCKNER GESAMTAUSGABE 1. Solo 1. 2. in F ‰. r j . r & c ∑ ∑ ∑ bœ œ ‰‰ j ‰ ∑ Horn . œ. œ. p 3. 4. in Es & c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ NEW ANTON BRUCKNER COMPLETE EDITION Trompete 1. 2. in C & c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alt, Tenor b B b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Posaune Die Anfangstakte der Symphonie Nr. 1 (Linzer Fassung) im Vergleich The first bars of Symphony No. 1 (Linz Version) – a comparison Bass ? (Detail): (detail): bbb c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Pauken in C u. G ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Internationale Bruckner-Gesellschaft – Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Allegro International Bruckner Society – Austrian National Library Violine 1 b & b b c Ó ‰. r ≈ œ œ ≈œ ≈ ≈ j ‰‰. r j ‰‰. r ≈œ œ œ œ œ œ ≈nœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ≈œ œ p Violine 2 b Patronanz: Wiener Philharmoniker & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ divisi Patronage: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Viola B bbb c œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ œ œ œ p . Violoncello ? b b b c œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ œ œ œ p . Kontrabass ? b c œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ b b . œ. -

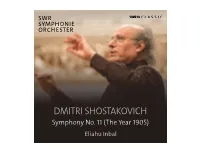

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No

SWR SYMPHONIE ORCHESTER DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 11 (The Year 1905) Eliahu Inbal Mit Kamerablick (1906–1975) DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Mit dem Tod Stalins 1953 begann in der Sowjet- Die jüngere russische Geschichte war schon Sinfonie Nr. 11 g-Moll op. 103 (Das Jahr 1905) union eine neue Periode, die vorsichtige vorher oft ein Thema in Schostakowitschs Symphony No.11 in G Minor Op.103 (The Year 1905) Hoffnung auf eine Verbesserung des innen- sinfonischem Schaffen – man denke an seine politischen Klimas weckte. Für den jahrelang 7. Sinfonie, die „Leningrader“ (1942). In dieser 1 I Der Platz vor dem Palast. Adagio 13:32 drangsalierten und gedemütigten Komponis- Zeit des Aufbruchs war ihm eine Erinnerung an The Palace Square. Adagio ten Dmitri Schostakowitsch bedeutete sie die Wurzeln der Sowjetunion ein besonderes jedenfalls eine Erleichterung seiner Arbeit. Anliegen. In den ersten Jahren des 20. Jahr- 2 II Der neunte Januar. Allegro 18:09 Gemaßregelte frühere Werke durften wieder hunderts hatte sich die schon vorher missliche The 9th of January. Allegro gespielt werden, für neue gab es günstigere Lage der Arbeiter in Russland dramatisch ver- 3 III Ewiges Gedenken. Adagio 11:08 Startbedingungen. Das setzte bei ihm neue schlechtert, die Unterdrückung durch Landbe- In memoriam. Adagio schöpferische Energien frei. Die noch im sel- sitzer und Fabrikanten nahm immer brutalere 4 IV Sturmläuten. Allegro non troppo 15:26 ben Jahr fertig gestellte 10. Sinfonie wurde zur Formen an. Tocsin. Allegro non troppo Abrechnung mit dem Diktator, die zwar Dis- kussionen auslöste, aber überwiegend auf Zu- Am 22. Januar 1905 kam es zu einem General- stimmung stieß. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F. -

Selected Male Part-Songs of Anton Bruckner by Justin Ryan Nelson

Songs in the Night: Selected Male Part-songs of Anton Bruckner by Justin Ryan Nelson, B.M., M.M. A Dissertation In Choral Conducting Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved John S. Hollins Chair of Committee Alan Zabriskie Angela Mariani Smith Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May 2019 Copyright 2019, Justin Ryan Nelson Texas Tech University, Justin R. Nelson, May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To begin, I would like to thank my doctoral dissertation committee: Dr. John Hollins, Dr. Alan Zabriskie, and Dr. Angela Mariani Smith, for their guidance and support in this project. Each has had a valuable impact upon my life, and for that, I am most grateful. I would also like to thank Professor Richard Bjella for his mentorship and for his uncanny ability to see potential in students who cannot often see it in themselves. In addition, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Alec Cattell, Assistant Professor of Practice, Humanities and Applied Linguistics at Texas Tech University, for his word-for-word translations of the German texts. I also wish to acknowledge the following instructors who have inspired me along my academic journey: Dr. Korre Foster, Dr. Carolyn Cruse, Dr. Eric Thorson, Mr. Harry Fritts, Ms. Jean Moore, Dr. Sue Swilley, Dr. Thomas Milligan, Dr. Sharon Mabry, Dr. Thomas Teague, Dr. Jeffrey Wood, and Dr. Ann Silverberg. Each instructor made an investment of time, energy, and expertise in my life and musical growth. Finally, I wish to acknowledge and thank my family and friends, especially my father and step-mother, George and Brenda Nelson, for their constant support during my graduate studies.