Chapter 10 Umatilla-Walla Walla Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Creek WSC Assessment.Pdf

Gilliam County Hay Creek/Scott Canyon Watershed Assessment • i Hay Creek / Scott Canyon Watershed Assessment Prepared by the Gilliam County Natural Resources Department for the Hay Creek/Scott Canyon Working Group Principal Author: Sue Greer, Contract Watershed Assessment Staff with assistance from: Susie Anderson, Watershed Coordinator, Gilliam-East John Day Watershed Council George Meyers, SWCD Watershed Technical Specialist June, 2003 Gilliam County Hay Creek/Scott Canyon Watershed Assessment • ii Hay Creek & Scott Canyon Watershed Gilliam County, Oregon Scott Canyon Highway 19 N Highway 206 Hay Creek Watershed Scott Canyon Watershed Stream Flow County Roads State Highways Condon Gilliam County Hay Creek/Scott Canyon Watershed Assessment • iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION Goals and Objectives of Hay Creek / Scott Canyon Working Group. 1 Agencies & Jurisdictions. 2 Legislation and Management Plans . 4 CHAPTER 2 – WATERSHED OVERVIEW Watershed Description. 5 Ecoregions . 6 Land Ownership . 7 Land Use . 7 Noxious & Invasive Weeds . 8 Fish & Wildlife . 9 Population . 9 Climate & Precipitation . 9 Vegetation Zones . 11 Soils . 12 CHAPTER 3 – HISTORICAL CONDITIONS Historical Timeline. 16 Introduction . 17 Geology. 17 Climate . 18 Vegetation. 18 Native American Use. 19 Presence of Fish & Wildlife. 20 Natural Disturbance Patterns . 20 Settlement . 21 Livestock & Farming . 22 Roads & Rails. 23 City Water Supply. 23 CHAPTER 4 – CHANNEL HABITAT TYPES & CHANNEL MORPHOLOGY Introduction . 25 Methods . 25 Potential of Restoration basis CHTs. 26 CHT Description & Analysis . 27 Fish Barriers. 29 CHAPTER 5 – HYDROLOGY & WATER USE Introduction . 31 History . 31 Peak Stream Flows . 32 Water Rights . 32 Ground Water. 33 Road Density . 34 Gilliam County Hay Creek/Scott Canyon Watershed Assessment • iv CHAPTER 6 – SEDIMENT SOURCES Introduction . -

Gilliam County Emergency Management

Gilliam County Multi-Jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Prepared for: Gilliam County, Arlington, Condon, and Lonerock © 2013, University of Oregon’s Community Service Center Photos: Oregon State Archives Gilliam County Multi-jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Report for: Gilliam County City of Arlington City of Condon City of Lonerock 221 South Oregon Street Condon, Oregon 97823 Prepared by: University of Oregon’s Community Service Center: Resource Assistance to Rural Environments & Oregon Partnership for Disaster Resilience 1209 University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon 97403-1209 January 2013 (This page intentionally left blank) Special Thanks & Acknowledgements GilliAm County developed this NaturAl HazArds MitigAtion PlAn through A regionAl pArtnership funded by the Federal Emergency MAnAgement Agency’s Pre-DisAster MitigAtion Competitive GrAnt ProgrAm. FEMA AwArded the Mid-ColumbiA Gorge Region grAnt to support the update of naturAl hazArd mitigAtion plAns for eight counties in the region. The region’s plAnning process utilized A four-phased plAnning process, plAn templAtes And plAn development support provided by Resource AssistAnce for RurAl Environments (RARE) and the Oregon PArtnership for DisAster Resilience (OPDR) At the University of Oregon’s Community Service Center. This project would not have been possible without technicAl And financiAl support provided by the Mid-ColumbiA Council of Governments. Regional partners include: • Mid-ColumbiA Council of Governments • Oregon MilitAry DepArtment – Office of Emergency -

Operation and Maintenance of the Umatilla Project and Umatilla Basin Project, Umatilla County

UNITED STA1ES OEPARlMENTOF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE West Coast Region 1201 NE Lloyd Boulevard , Su~e 1100 Portland, Oregon 97232-1274 July 2, 2019 Refer to NMFS No: WCR-2018-10032 Dawn Wiedmeier Area Manager Columbia-Cascades Area Office U.S. Bureau of Reclamation 1917 Marsh Road Yakima, Washington 98901 Re: Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion and Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act Essential Fish Habitat Consultation on Operation and Maintenance of the Umatilla Project and Umatilla Basin Project, Umatilla County. Oregon, HUC 17070103 (Umatilla), HUC 17070101 (Columbia-Lake Wallula). Enclosed is a biological opinion (opinion) prepared by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) pursuant to section 7(a)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) on the effects of operating the Umatilla Project and the Umatilla Basin Project in Umatilla County, Oregon. NMFS concludes in this opinion that the operation of the Umatilla and Umatilla Basin Projects is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the following ESA-listed species: Middle Columbia River steelhead Upper Columbia River steelhead Snake River Basin steelhead Snake River sockeye salmon Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon NMFS also concludes that the proposed action is not likely to destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat. As required by section 7 of the ESA, NMFS included reasonable and prudent measures with nondiscretionary terms and conditions that NMFS believes are necessary to avoid or minimize the effect of incidental take caused by this action. -

The Missoula Flood

THE MISSOULA FLOOD Dry Falls in Grand Coulee, Washington, was the largest waterfall in the world during the Missoula Flood. Height of falls is 385 ft [117 m]. Flood waters were actually about 260 ft deep [80 m] above the top of the falls, so a more appropriate name might be Dry Cataract. KEENAN LEE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES GOLDEN COLORADO 80401 2009 The Missoula Flood 2 CONTENTS Page OVERVIEW 2 THE GLACIAL DAM 3 LAKE MISSOULA 5 THE DAM FAILURE 6 THE MISSOULA FLOOD ABOVE THE ICE DAM 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Eddy Narrows 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Perma Narrows 7 Catastrophic Flood Features at Camas Prairie 9 THE MISSOULA FLOOD BELOW THE ICE DAM 13 Rathdrum Prairie and Spokane 13 Cheny – Palouse Scablands 14 Grand Coulee 15 Wallula Gap and Columbia River Gorge 15 Portland to the Pacific Ocean 16 MULTIPLE MISSOULA FLOODS 17 AGE OF MISSOULA FLOODS 18 SOME REFERENCES 19 OVERVIEW About 15 000 years ago in latest Pleistocene time, glaciers from the Cordilleran ice sheet in Canada advanced southward and dammed two rivers, the Columbia River and one of its major tributaries, the Clark Fork River [Fig. 1]. One lobe of the ice sheet dammed the Columbia River, creating Lake Columbia and diverting the Columbia River into the Grand Coulee. Another lobe of the ice sheet advanced southward down the Purcell Trench to the present Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho and dammed the Clark Fork River. This created an enormous Lake Missoula, with a volume of water greater than that of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined [530 mi3 or 2200 km3]. -

Touchet Endemic Summer Steelhead HGMP to NOAA Fisheries in 2010 for a Section 10(A)(1)(A) Permit

WDFW Touchet River Endemic Stock Summer Steelhead - Touchet River Release HATCHERY AND GENETIC MANAGEMENT PLAN (HGMP) Hatchery Program: Mid-Columbia Summer Steelhead –Touchet River Stock: Lyons Ferry Hatchery Complex Species or Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead Hatchery Stock: Agency/Operator: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Watershed and Region: Touchet River / Walla Walla River / Mid- Columbia Basin, Washington State Date Submitted: April 20, 2002; November 29, 2010 Date Last Updated: November 6, 2015 WDFW - Touchet River Endemic Stock HGMP 1 Executive Summary ESA Permit Status: In 2010 the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) submitted a Hatchery Genetic Management Plan (HGMP) for the Lyons Ferry Hatchery (LFH) Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead 50,000 release of yearling smolts into the Touchet River program. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) are now re-submitting an HGMP for this yearling program to update the description of the current program. Both the Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead (O. Mykiss), Mid-Columbia ESU summer steelhead population, listed as threatened under the ESA as part of the Mid-Columbia River ESU (March 25, 1999; FR 64 No. 57: 14517-14528) and Wallowa Stock summer steelhead (O. Mykiss), (not ESA-listed) are currently produced at WDFW’s LFH and released into the Touchet River. This document covers only the Tucannon Endemic Steelhead program. The proposed hatchery program may slowly phase out the Wallowa stock from the Touchet River in the future. This will depend on the performance of the Touchet River endemic steelhead stock, and decisions reached with the co-managers for full implementation. -

DRAFT Mckay Creek National Wildlife Refuge Turkey, Dove, Deer, and Elk Hunt Plan

DRAFT McKay Creek National Wildlife Refuge Turkey, Dove, Deer, and Elk Hunt Plan June 2019 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service McKay Creek National Wildlife Refuge Mid-Columbia River NWR Complex 64 Maple Street Burbank, WA 99323 Submitted By: Project Leader ______________________________________________ ____________ Signature Date Concurrence: Refuge Supervisor ______________________________________________ ____________ Signature Date Approved: Regional Chief, National Wildlife Refuge System ______________________________________________ ____________ Signature Date Table of Contents I. Introduction……………………………...…………………………………………4 II. Statement of Objectives…………………..………………………………………..6 III. Description of Hunting Program……………………………………………….....7 A. Areas to be Opened to Hunting…………………………………...7 B. Species to be Taken, Hunting Periods, Hunting Access………….9 C. Hunter Permit Requirements (if applicable)……………………..10 D. Consultation and Coordination with the State…………………...10 E. Law Enforcement………………………………………………...11 F. Funding and Staffing Requirements …………………………….11 IV. Conduct of the Hunt Program….…………………………………………………11 A. Hunter Permit Application, Selection, and/or Registration Procedures (if applicable).………………………………………...11 B. Refuge-Specific Regulations ……………………………………..12 C. Relevant State Regulations ……………………………………….13 D. Other Rules and Regulations for Hunters…………………………14 V. Public Engagement A. Outreach Plan for Announcing and Publicizing the Hunt………...15 B. Anticipated Public Reaction to the Hunting Program ……………15 C. How the Public Will -

This File Was Created by Scanning the Printed Publication

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Editors SHARON E. CLARKE is a geographer and GIS analyst, Department of Forest Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; and SANDRA A. BRYCE is a biogeographer, Dynamac Corporation, Environmental Protection Agency, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Western Ecology Division, Corvallis, OR 97333. This document is a product of cooperative research between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; the Forest Science De- partment, Oregon State University; and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Cover Artwork Cover artwork was designed and produced by John Ivie. Abstract Clarke, Sharon E.; Bryce, Sandra A., eds. 1997. Hierarchical subdivisions of the Columbia Plateau and Blue Mountains ecoregions, Oregon and Washington. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-395. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 114 p. This document presents two spatial scales of a hierarchical, ecoregional framework and provides a connection to both larger and smaller scale ecological classifications. The two spatial scales are subregions (1:250,000) and landscape-level ecoregions (1:100,000), or Level IV and Level V ecoregions. Level IV ecoregions were developed by the Environmental Protection Agency because the resolution of national-scale ecoregions provided insufficient detail to meet the needs of state agencies for estab- lishing biocriteria, reference sites, and attainability goals for water-quality regulation. For this project, two ecoregions—the Columbia Plateau and the Blue Mountains— were subdivided into more detailed Level IV ecoregions. -

Gold and Fish Pamphlet: Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining

WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE Gold and Fish Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining May 2021 WDFW | 2020 GOLD and FISH - 2nd Edition Table of Contents Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining Rules 1 Agencies with an Interest in Mineral Prospecting 1 Definitions of Terms 8 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwater Without Timing Restrictions 12 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwaters With Timing Restrictions 14 Mineral Prospecting on Ocean Beaches 16 Authorized Work Times 17 Penalties 42 List of Figures Figure 1. High-banker 9 Figure 2. Mini high-banker 9 Figure 3. Mini rocker box (top view and bottom view) 9 Figure 4. Pan 10 Figure 5. Power sluice/suction dredge combination 10 Figure 6. Cross section of a typical redd 10 Fig u re 7. Rocker box (top view and bottom view) 10 Figure 8. Sluice 11 Figure 9. Spiral wheel 11 Figure 10. Suction dredge . 11 Figure 11. Cross section of a typical body of water, showing areas where excavation is not permitted under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 12. Permitted and prohibited excavation sites in a typical body of water under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 13. Limits on excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate on stream banks 14 Figure 14. Excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate within the wetted perimeter is not permitted 1 4 Figure 15. Cross section of a typical body of water showing unstable slopes, stable areas, and permissible or prohibited excavation sites under rules for mineral prospecting with timing restrictions Dashed lines indicates areas where excavation is not permitted 15 Figure 16. -

Count of LLID and Sum of Miles Per State, RU, and Core Area for Current Presence

Count of LLID and Sum of Miles Per State, RU, and Core Area For Current Presence STATE wa RecoveryUnit CORE_AREA NAME SumOfMILES Chilliwack River 0.424000 Columbia River 194.728000 Depot Creek 0.728000 Kettle River 0.001000 Palouse River 6.209000 Silesia Creek 0.374000 Skagit River 0.258000 Snake River 58.637000 Sumas River 1.449000 Yakima River 0.845000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = (10 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 263.653000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 10 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 263.653000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 10 Saturday, January 01, 2005 Page 1 of 46 STATE wa RecoveryUnit Clark Fork River Basin CORE_AREA Priest Lake NAME SumOfMILES Bench Creek 2.114000 Cache Creek 2.898000 Gold Creek 3.269000 Jackson Creek 3.140000 Kalispell Creek 15.541000 Muskegon Creek 1.838000 North Fork Granite Creek 6.642000 Sema Creek 4.365000 South Fork Granite Creek 12.461000 Tillicum Creek 0.742000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = Priest Lake (10 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 53.010000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 10 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 53.010000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 10 RecoveryUnit Clearwater River Basin CORE_AREA Lower and Middle Fork Clearwater River NAME SumOfMILES Bess Creek 1.770000 Snake River 0.077000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = Lower and Middle Fork Clearwater River (2 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 1.847000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 2 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 1.847000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 2 Saturday, January 01, 2005 Page 2 of 46 STATE wa RecoveryUnit Columbia River CORE_AREA NAME SumOfMILES Columbia River 98.250000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' -

Umatilla National Forest

Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report Umatilla National Forest FOREST SUPERVISOR OFFICE 2517 SW Hailey Avenue Pendleton, Oregon 97801 (541) 278-3716 Jeff D. Blackwood, Forest Supervisor ---------- HEPPNER RANGER DISTRICT P.O. Box 7 Heppner, Oregon 97836 (541) 676-9187 Andrei Rykoff, District Ranger NORTH FORK JOHN DAY RANGER DISTRICT P.O. Box 158 Ukiah, Oregon 97880 (541) 427-3231 Craig Smith-Dixon, District Ranger POMEROY RANGER DISTRICT 71 West Main Pomeroy, Washington 99347 (509) 843-1891 Monte Fujishin, District Ranger WALLA WALLA RANGER DISTRICT 1415 West Rose Street Walla Walla, Washington 99362 (509) 522-6290 Mary Gibson, District Ranger U-1 Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report U-2 Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report SECTION U Table of Contents Page MONITORING ITEMS NOT REPORTED THIS YEAR.....................................................................U- 4 FOREST PLAN AMENDMENTS FOR FY2001................................................................................U- 4 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS ..................................................................................U- 5 FOREST PLAN MONITORING ITEMS Item 3 Water Quantity .........................................................................................................U-10 Item 4 Water Quality............................................................................................................U-12 Item 5 Stream Temperature ................................................................................................U-15 Item 6 Stream Sedimentation..............................................................................................U-20 -

Walla Walla, Mill Creek, and Coppei Geomorphic Assessment

Walla Walla River, Mill Creek, United States Department of and Coppei Creek Agriculture Forest Geomorphic Assessment Service May 2010 Walla Walla County Conservation District and U.S. Forest Service, TEAMS Enterprise Unit Prepared by: Thomas Brian Bair, Project Fisheries Biologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Michael McNamara, Hydrologist/Geologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Anthony Olegario, Fisheries/Engineer, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Chad Hermandorfer, Hydrologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Katherine Carsey, Botanist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Compiled: April, 2010; Revised: May 2010 Acknowledgements: Thanks to all the helpful staff at the Walla Walla County Conservation District including Rick Jones, Mike Denny, Jonathon Thompson, Audrey Ahman, and others. Thanks also to landowners Ron Johnson and other landowners for allowing us access to their property and cooperating with our study. Thanks lastly to all the U.S. Forest Service TEAMS members who contributed to this document. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. -

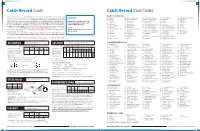

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.