Preliminary Environmental Assessment (EA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchet Endemic Summer Steelhead HGMP to NOAA Fisheries in 2010 for a Section 10(A)(1)(A) Permit

WDFW Touchet River Endemic Stock Summer Steelhead - Touchet River Release HATCHERY AND GENETIC MANAGEMENT PLAN (HGMP) Hatchery Program: Mid-Columbia Summer Steelhead –Touchet River Stock: Lyons Ferry Hatchery Complex Species or Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead Hatchery Stock: Agency/Operator: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Watershed and Region: Touchet River / Walla Walla River / Mid- Columbia Basin, Washington State Date Submitted: April 20, 2002; November 29, 2010 Date Last Updated: November 6, 2015 WDFW - Touchet River Endemic Stock HGMP 1 Executive Summary ESA Permit Status: In 2010 the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) submitted a Hatchery Genetic Management Plan (HGMP) for the Lyons Ferry Hatchery (LFH) Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead 50,000 release of yearling smolts into the Touchet River program. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) are now re-submitting an HGMP for this yearling program to update the description of the current program. Both the Touchet River Endemic Summer Steelhead (O. Mykiss), Mid-Columbia ESU summer steelhead population, listed as threatened under the ESA as part of the Mid-Columbia River ESU (March 25, 1999; FR 64 No. 57: 14517-14528) and Wallowa Stock summer steelhead (O. Mykiss), (not ESA-listed) are currently produced at WDFW’s LFH and released into the Touchet River. This document covers only the Tucannon Endemic Steelhead program. The proposed hatchery program may slowly phase out the Wallowa stock from the Touchet River in the future. This will depend on the performance of the Touchet River endemic steelhead stock, and decisions reached with the co-managers for full implementation. -

Gold and Fish Pamphlet: Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining

WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE Gold and Fish Rules for Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining May 2021 WDFW | 2020 GOLD and FISH - 2nd Edition Table of Contents Mineral Prospecting and Placer Mining Rules 1 Agencies with an Interest in Mineral Prospecting 1 Definitions of Terms 8 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwater Without Timing Restrictions 12 Mineral Prospecting in Freshwaters With Timing Restrictions 14 Mineral Prospecting on Ocean Beaches 16 Authorized Work Times 17 Penalties 42 List of Figures Figure 1. High-banker 9 Figure 2. Mini high-banker 9 Figure 3. Mini rocker box (top view and bottom view) 9 Figure 4. Pan 10 Figure 5. Power sluice/suction dredge combination 10 Figure 6. Cross section of a typical redd 10 Fig u re 7. Rocker box (top view and bottom view) 10 Figure 8. Sluice 11 Figure 9. Spiral wheel 11 Figure 10. Suction dredge . 11 Figure 11. Cross section of a typical body of water, showing areas where excavation is not permitted under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 12. Permitted and prohibited excavation sites in a typical body of water under rules for mineral prospecting without timing restrictions Dashed lines indicate areas where excavation is not permitted 12 Figure 13. Limits on excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate on stream banks 14 Figure 14. Excavating, collecting, and removing aggregate within the wetted perimeter is not permitted 1 4 Figure 15. Cross section of a typical body of water showing unstable slopes, stable areas, and permissible or prohibited excavation sites under rules for mineral prospecting with timing restrictions Dashed lines indicates areas where excavation is not permitted 15 Figure 16. -

Count of LLID and Sum of Miles Per State, RU, and Core Area for Current Presence

Count of LLID and Sum of Miles Per State, RU, and Core Area For Current Presence STATE wa RecoveryUnit CORE_AREA NAME SumOfMILES Chilliwack River 0.424000 Columbia River 194.728000 Depot Creek 0.728000 Kettle River 0.001000 Palouse River 6.209000 Silesia Creek 0.374000 Skagit River 0.258000 Snake River 58.637000 Sumas River 1.449000 Yakima River 0.845000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = (10 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 263.653000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 10 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 263.653000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 10 Saturday, January 01, 2005 Page 1 of 46 STATE wa RecoveryUnit Clark Fork River Basin CORE_AREA Priest Lake NAME SumOfMILES Bench Creek 2.114000 Cache Creek 2.898000 Gold Creek 3.269000 Jackson Creek 3.140000 Kalispell Creek 15.541000 Muskegon Creek 1.838000 North Fork Granite Creek 6.642000 Sema Creek 4.365000 South Fork Granite Creek 12.461000 Tillicum Creek 0.742000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = Priest Lake (10 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 53.010000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 10 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 53.010000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 10 RecoveryUnit Clearwater River Basin CORE_AREA Lower and Middle Fork Clearwater River NAME SumOfMILES Bess Creek 1.770000 Snake River 0.077000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' = Lower and Middle Fork Clearwater River (2 detail records) SumMilesPerCoreArea 1.847000 CountLLIDPerCoreArea 2 SumMilesPerRUAndCoreArea 1.847000 CountLLIDPerRUAndCoreArea 2 Saturday, January 01, 2005 Page 2 of 46 STATE wa RecoveryUnit Columbia River CORE_AREA NAME SumOfMILES Columbia River 98.250000 Summary for 'CORE_AREA' -

Umatilla National Forest

Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report Umatilla National Forest FOREST SUPERVISOR OFFICE 2517 SW Hailey Avenue Pendleton, Oregon 97801 (541) 278-3716 Jeff D. Blackwood, Forest Supervisor ---------- HEPPNER RANGER DISTRICT P.O. Box 7 Heppner, Oregon 97836 (541) 676-9187 Andrei Rykoff, District Ranger NORTH FORK JOHN DAY RANGER DISTRICT P.O. Box 158 Ukiah, Oregon 97880 (541) 427-3231 Craig Smith-Dixon, District Ranger POMEROY RANGER DISTRICT 71 West Main Pomeroy, Washington 99347 (509) 843-1891 Monte Fujishin, District Ranger WALLA WALLA RANGER DISTRICT 1415 West Rose Street Walla Walla, Washington 99362 (509) 522-6290 Mary Gibson, District Ranger U-1 Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report U-2 Umatilla - 2001 Monitoring Report SECTION U Table of Contents Page MONITORING ITEMS NOT REPORTED THIS YEAR.....................................................................U- 4 FOREST PLAN AMENDMENTS FOR FY2001................................................................................U- 4 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS ..................................................................................U- 5 FOREST PLAN MONITORING ITEMS Item 3 Water Quantity .........................................................................................................U-10 Item 4 Water Quality............................................................................................................U-12 Item 5 Stream Temperature ................................................................................................U-15 Item 6 Stream Sedimentation..............................................................................................U-20 -

Walla Walla, Mill Creek, and Coppei Geomorphic Assessment

Walla Walla River, Mill Creek, United States Department of and Coppei Creek Agriculture Forest Geomorphic Assessment Service May 2010 Walla Walla County Conservation District and U.S. Forest Service, TEAMS Enterprise Unit Prepared by: Thomas Brian Bair, Project Fisheries Biologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Michael McNamara, Hydrologist/Geologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Anthony Olegario, Fisheries/Engineer, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Chad Hermandorfer, Hydrologist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Katherine Carsey, Botanist, Forest Service TEAMS Enterprise Unit Compiled: April, 2010; Revised: May 2010 Acknowledgements: Thanks to all the helpful staff at the Walla Walla County Conservation District including Rick Jones, Mike Denny, Jonathon Thompson, Audrey Ahman, and others. Thanks also to landowners Ron Johnson and other landowners for allowing us access to their property and cooperating with our study. Thanks lastly to all the U.S. Forest Service TEAMS members who contributed to this document. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. -

Catch Record Cards & Codes

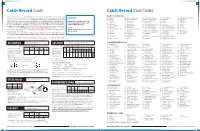

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Identification of Most Probable Stressors to Aquatic Life in the Touchet River, Washington

EPA/600/R-08/145 | January 2010 | www.epa.gov/ncea Identification of Most Probable Stressors to Aquatic Life in the Touchet River, Washington National Center for Environmental Assessment Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC 20460 EPA/600/R-08/145 January 2010 Identification of Most Probable Stressors to Aquatic Life in the Touchet River, Washington National Center for Environmental Assessment Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Cincinnati, OH 45268 NOTICE The Washington State Department of Ecology and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through its Office of Research and Development jointly prepared this report. It has been subjected to the Agency’s peer and administrative review and has been approved for publication as an EPA document. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ABSTRACT The Washington State Department of Ecology (WSDE) currently practices “single-entry” total maximum daily load (TMDL) studies. A single-entry TMDL addresses multiple water quality impairments concurrently, which can reduce sampling costs, organize sampling group efforts, and provide an objective framework for basing management decisions in the regulatory process. The Touchet River, a subwatershed of the Walla Walla River in eastern Washington State, was listed for fecal coliform bacteria, temperature, and pH water quality impairments and slated for a single-entry TMDL. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA)’s Stressor Identification procedures were used to identify and prioritize factors causing biological impairment and to develop effective restoration plans for this river. Six sites were sampled along the Touchet River over a two-year period; parameters measured included WSDE benthic macroinvertebrate assemblage metrics and physical habitat measures; chemical analysis of pesticides and other pollutants; and in-situ temperature and pH measurements. -

Louis Tellier to the Pacific Northwest Earlier Than 1834 by Chalk

Louis Tellier To The Pacific Northwest earlier than 1834 By Chalk Courchane Louis Tellier was born in Trois Rivieres, Quebec, Canada about 1806/1809. Louis Tellier who appears briefly in the St. Paul register was a Hudson's Bay Company employee who seems to have settled for a time on French Prairie” in 1834 as a millwright. Joseph LaRocque, built the first Frenchtown cabin in 1823. The Louis Tellier family, across the field from the LaRocques, arrived in 1834 from Montana. Louis went to work for Marcus Whitman as a millwright in 1836. Tellier was likely stationed at Flathead Post before coming to Frenchtown. http://www.frenchtownpartners.zoomshare.com/ He is said to have helped Whitman construct his second grist mill, the first having been burned by the Indians, and to act as the mission miller thereafter." But by 1855 was living at Frenchtown, near Walla Walla, with a native wife (Angeline Pend d'Oreille) and six children. His claim lay a short distance to the west of the old Whitman Mission, next to that of Michel Pelisser, their families intermarried; later records are carried in the Walla Walla register, which included Frenchtown as a mission." From "Catholic Church Records in the Pacific Northwest" by Munnick and Warner, p-A91 and Catholic Church Records of the Pacific Northwest- Missions of St. Ann and St. Rose of the Cayuse 1847-1888, Walla Walla and Frenchtown 1859-1872 and Frenchtown 1872-1888." by Harriet D. Munnick, Binford & Mort Pub., Portland, Oregon, 1989, Annotations" From Oregon Territory Census 1850 taken by Assistant Marshall W.H. -

Temperature Analysis

Appendix A Stream Temperature Analysis Vegetation, Hydrology and Morphology Walla Walla Subbasin August 2005 This Assessment was prepared in partnership between the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the Walla Walla Basin Watershed Council Authors: Don Butcher, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Bob Bower, Walla Walla Basin Watershed Council Principal Contributors/Consultation: Brian Wolcott, Walla Walla Basin Watershed Council Brian Kasper, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Other Contributors: Washington Department of Ecology Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Umatilla National Forest, Supervisors and District Offices Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Water Resources Department US Army Corps of Engineers USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service For more information contact: Don Butcher, Basin Coordinator/Analyst Oregon Department of Environmental Quality 700 SE Emigrant, Suite 330 Pendleton, Oregon 97801 [email protected] DEQ Submittal to US EPA Page 1 Walla Walla Subbasin Temperature TMDL River Temperature Analysis Vegetation, Hydrology and Morphology Walla Walla River Subbasin Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................... 4 1.1 Scale & Location 4 1.2 Interstate Coordination 5 1.3 Overview: Analysis and Stream Heating Processes 5 1.4 Stream Assessment for Oregon Temperature Standard 11 1.4.1 Summary of Stream Temperature TMDL Approach 11 1.4.2 Limitations of Stream Temperature TMDL Approach 12 1.5 Basin Description 14 1.5.1 Topography and Map View 14 1.5.2 Climate 17 1.5.3 River Flow 17 1.5.4 Population and Local Government 17 1.5.5 Point sources 17 1.5.6 Land Use & Irrigation 18 1.5.7 Vegetation 18 CHAPTER 2. -

Chapter 10 Umatilla-Walla Walla Rivers

Chapter: 10 States: Oregon and Washington Recovery Unit Name: Umatilla -Walla Walla Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to recover and/or protect the species. Recovery plans are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and, in this case, with the assistance of recovery unit teams, State and Tribal agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or indicate the approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Chapter 11, Umatilla- Walla Walla Recovery Unit, Oregon and Washington. 153 p. In: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) Draft Recovery Plan. Portland, Oregon. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Umatilla-Walla Walla recovery unit team includes technical experts from Oregon and Washington. A bull trout technical working group made up of area biologists was organized in the early 1990's to survey and monitor bull trout populations in the Umatilla and upper Walla Walla Basins. -

South Fork Walla Walla Landowner Access Environmental Assessment Ea # Or-035-06-03

SOUTH FORK WALLA WALLA LANDOWNER ACCESS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA # OR-035-06-03 1 of 54 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ..........................................4 Proposed Action..........................................................................................................5 Location ......................................................................................................................5 Environmental Analysis and Decision Process...........................................................6 Public and Government Input Summary and Issue Development..............................7 Management Direction and Conformance with Existing Plans..................................8 CHAPTER 2 – PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES ................................10 Design Features and Mitigations Common to all Alternatives.................................10 No Action Alternative...............................................................................................11 Alternative 1. Preferred Alternative: Longer Window of Property Owner Access with Full-sized Vehicles ...........................................................................................12 Alternative 1. A. Preferred Alternative: Modify the Existing Route to Avoid Chinook Redds (modify some wet crossings) ..........................................................12 Alternative 1. B. Allow Existing Routes by Deterring Spawning on Crossings with Suitable Chinook spawning Gravels.........................................................................14 -

Tucannon and Touchet River Endemic Broodstock Development Hatchery

Tucannon and Touchet River Endemic Broodstock Development Hatchery Program Review 2000‐2012 Joseph D. Bumgarner Mark L. Schuck Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Snake River Lab 401 South Cottonwood Dayton, WA 99328 This program is a cooperative effort of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Nez Perce Tribe and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The program is funded by the Bonneville Power Administration and administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service under the Lower Snake River Compensation Plan. INTRODUCTION and BACKGROUND This paper provides background information, program development history and an assessment of program performance for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (WDFW) Tucannon and Touchet rivers endemic stock summer steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) hatchery program. The coverage period is from program initiation in 2000 to the present (spring of 2012). A precipitous decline in numbers of Snake River steelhead and other anadromous fish between 1962 and the mid 1970s alarmed management agencies such as the WDFW. The rapid decline in steelhead and a commensurate loss of recreational opportunity for Washington’s residents spurred Washington to partner with other State and Federal management agencies, where they negotiated with federal agencies such as the Corps of Engineers (COE) to mitigate for adult fish losses to anadromous populations and lost resident fishing opportunity caused by construction and operation of the four lower Snake River power dams. The Lyons Ferry and Wallowa stock steelhead programs were initiated early on to achieve mitigation goals and have been described in other LSRCP summary documents. Snake River and Mid‐Columbia summer steelhead populations were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1997.