Training Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan Written by DeQuincy A. Lezine, PhD and Noah J. Whitaker, MBA For those who struggle, those who have been lost, those left behind, may you find hope… Fresno Cares 2018 Introduction 4 Background and Rationale 5 How Suicide Impacts Fresno County 5 The Fresno County Suicide Prevention Collaborative 7 History 8 Capacity-Building 9 Suicide Prevention in Schools (AB 2246) 10 Workgroups 10 Data 11 Communication 11 Learning & Education 12 Health Care 13 Schools 14 Justice & First Responders 15 Understanding Suicide 16 Overview: the Suicidal crisis within life context 17 The Suicidal Crisis: Timeline of suicidal crisis and prevention 22 Levels of Influence: The Social-Ecological Model 23 Identifying and Characterizing Risk 24 Understanding How Risk Escalates Into Suicidal Thinking 26 Warning Signs: Recognizing when someone may be suicidal 27 Understanding How Suicidal Thinking Turns into Behavior 28 Understanding How a Suicide Attempt Becomes a Suicide 28 Understanding How Suicide Affects Personal Connections 29 Stopping the Crisis Path 30 Comprehensive Suicide Prevention in Fresno County 31 Health and Wellness Promotion 34 Prevention (Universal strategies) 34 Early Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Clinical Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Crisis Intervention and Postvention (Indicated strategies) 36 Where We are Now: Needs and Assets in Fresno County 37 Suicidal Thoughts and Feelings 37 Suicide Attempts 40 1 Suicide 41 Understanding -

Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention

2018 Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention A STUDY OF YOUTH SUICIDE IN FOUR COLORADO COUNTIES Presented to Attorney General Cynthia H. Coffman Colorado Office of the Attorney General By Health Management Associates 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary..............................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................11 Scope of the Problem........................................................................................................................................................11 Key Stakeholder Interviews...........................................................................................................................................13 Community Focus Groups.............................................................................................................................................. 17 School Policies & Procedures........................................................................................................................................27 Traditional Media & Suicide.......................................................................................................................................... -

Answer Key: Suicide Prevention

Personal Health Series Suicide Quiz Answer Key 1. List four factors that can increase a teen’s risk of suicide: Any four of the following: a psychological disorder, especially depression, bipolar disorder, and alcohol and/or drug use; feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness; previous suicide attempt; family history of depression or suicide; emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; lack of a support network, poor relationships with parents or peers, and feelings of social isolation; dealing with bisexuality or homosexuality in an unsupportive family or community or hostile school environment; perfectionism. 2. True or false: If a person talks about suicide, it means he or she is just looking for attention and won’t go through with it. 3. True or false: The danger of suicide has passed when a person begins to cheer up. 4. List four warning signs that someone is thinking about suicide: Any four of the following: talking about suicide or death in general; hinting he/she might not be around anymore; talking about feeling hopeless or feeling guilty; pulling away from friends or family; writing songs, poems, or letters about death, separation, or loss; giving away treasured possessions; losing the desire to do favorite things or activities; having trouble concentrating or thinking clearly; changing eating or sleeping habits; engaging in risky or self-destructive behaviors; losing interest in school and/or extra-curricular activities. 5. True or false: Once a person is suicidal, he or she is suicidal forever. 6. True or false: Most teens who attempt suicide really intend to die. 7. True or false: If a friend tells you she’s considering suicide and swears you to secrecy, you have to keep your promise. -

National Guidelines: Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide

Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force April 2015 Blank page Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Table of Contents Front Matter Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... i Task Force Co-Leads, Members .................................................................................................................. ii Reviewers .................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... iii National Guidelines Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Terminology: “Postvention” and “Loss Survivor” ....................................................................................... 4 Development and Purpose of the Guidelines ............................................................................................. 6 Audience of the Guidelines ........................................................................................................................ -

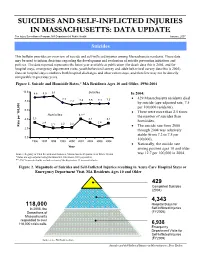

Suicides and Self-Inflicted Injuries in Massachusetts: Data Update

SSUUIICCIIDDEESS AANNDD SSEELLFF--IINNFFLLIICCTTEEDD IINNJJUURRIIEESS IINN MMAASSSSAACCHHUUSSEETTTTSS:: DDAATTAA UUPPDDAATTEE The Injury Surveillance Program, MA Department of Public Health January, 2007 Suicides This bulletin provides an overview of suicide and self-inflicted injuries among Massachusetts residents. These data may be used to inform decisions regarding the development and evaluation of suicide prevention initiatives and policies. The data reported represents the latest year available at publication (for death data this is 2004, and for hospital stays, emergency department visits, youth behavioral survey and adult behavioral survey data this is 2005). Data on hospital stays combines both hospital discharges and observation stays, and therefore may not be directly comparable to previous years. Figure 1. Suicide and Homicide Rates,* MA Residents Ages 10 and Older, 1996-2004 10.0 8.8 8.9 9.1 Suicides In 2004: 7.7 • 429 Massachusetts residents died 8.0 7.2 7.4 7.5 7.4 7.5 by suicide (age-adjusted rate, 7.5 per 100,000 residents). 6.0 • There were more than 2.5 times Homicides 4.1** the number of suicides than 4.0 3.3 3.2 3.1 2.4 2.4 homicides. 2.1 2.2 2.2 100,000 per Rate • The suicide rate from 2000 2.0 through 2004 was relatively stable (from 7.2 to 7.5 per 0.0 100,000). 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 • Nationally, the suicide rate Year among persons ages 10 and older Source: Registry of Vital Records and Statistics, Massachusetts Department of Public Health was 12.7 per 100,000 in 2004. -

Age Differences in Suicide Methods

Forensic Research & Criminology International Journal Research Article Open Access Age differences in suicide methods Abstract Volume 6 Issue 6 - 2018 Objective: There is not adequate research on suicide methods by age in Turkey. The purpose of the present study is to investigate whether there is any change in suicide methods Mustafa Demir by age over time and whether suicide methods significantly differ by age. State University of New York at Plattsburgh, USA Method: Secondary data about suicide from 2007 to 2015 were obtained from the Turkish Correspondence: Mustafa Demir, State University of New Statistical Institute. The number of suicide cases was 25,696. Direct standardization method York at Plattsburgh, USA, Tel +15185643305, was used to calculate suicide rates. Line charts were plotted to reveal the trends in suicide Email methods by age. Then, one-way anova (ANOVA) test was conducted to test whether suicide methods significantly differed by age. Received: June 05, 2017 | Published: December 11, 2018 Results: Among all ages, hanging was the most common suicide method, followed by firearm, jumping, intoxication, and cutting/burning among all age groups. Moreover, all of the other suicide methods increased except for cutting/burning among those aged 15- 24 years, except for firearm among those aged 25-44 years, except for hanging among those aged 45-64 years. Among those aged 65 and older, suicide by hanging decreased, however, suicide by other methods overall remained stable. The results also showed that with increasing age, suicide by hanging, jumping, and cutting increased, while suicide by firearm and intoxication decreased. In addition, the results of ANOVA test indicated that except for intoxication, all other suicide methods differed significantly by age groups. -

Oregon Youth Suicide Prevention Guidelines

Photograph by Jason Dessel (1998) OORREEGGOONN YYOOUUTTHH SSUUIICCIIDDEE PPRREEVVEENNTTIIOONN YOUTH SUICIDE PREVENTION INTERVENTION & POSTVENTION GUIDELINES A Resource for School Personnel Developed by The Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program A Program of Governor Angus S. King, Jr. And the Maine Children’s Cabinet May 2002 Modified for Oregon by Jill Hollingsworth, MA Looking Glass Youth and Family Services November 2007 (2nd revision) YOUTH SUICIDE PREVENTION, INTERVENTION & POSTVENTION GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. RATIONALE FOR DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING SUICIDE PREVENTION 4 AND INTERVENTION PROTOCOLS III. COMPONENTS OF SCHOOL-BASED SUICIDE PREVENTION 6 A. READINESS SURVEY FOR ADMINISTRATORS 9 IV. COMPONENTS OF SCHOOL- BASED SUICIDE INTERVENTION 13 A. ESTABLISHING SUICIDE PROTOCOLS WITHIN THE SCHOOL CRISIS 14 RESPONSE PLAN B. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN THE RISK OF SUICIDE HAS BEEN RAISED 14 C. GUIDELINES FOR MEDIUM TO HIGH RISK SITUATIONS 16 D. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN A SUICIDE INVOLVES A PACT 17 E. RESPONDING TO A STUDENT SUICIDE ATTEMPT ON SCHOOL PREMISES 18 F. GUIDELINES FOR A STUDENT SUICIDE ATTEMPT OFF SCHOOL PREMISES 19 G. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN A STUDENT RETURNS TO SCHOOL FOLLOWING 20 H. ABSENCE FOR SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR V. COMPONENTS OF SUICIDE POSTVENTION PLANNING 22 A. KEY CONSIDERATIONS 23 B. RESPONDING TO A SUICIDE 25 Appendix A – RESPONSE, a Comprehensive Suicide Awareness Program 32 Appendix B – Basic Suicide Prevention and Intervention Information 36 Appendix C – Short Version of Suicide Intervention and -

Homicide-Followed-By-Suicide Incidents Involving Child Victims

Homicide-Followed-by-Suicide Incidents Involving Child Victims Joseph E. Logan, PhD, MHS; Sabrina Walsh, DrPH; Nimeshkumar Patel, MA; Jeffrey E. Hall, PhD, MSPH Objectives: To describe homicide-fol- were parents/caregivers. Eighty-one per- lowed-by-suicide incidents involving cent of incidents with paternal perpetra- child victims Methods: Using 2003-2009 tors and 59% with maternal perpetrators National Violent Death Reporting Sys- were preceded by parental discord. Fifty- tem data, we characterized 129 incidents two percent of incidents with maternal based on victim and perpetrator demo- perpetrators were associated with mater- graphic information, their relationships, nal psychiatric problems. Conclusions: the weapons/mechanisms involved, and Strategies that resolve parental conflicts the perpetrators’ health and stress-re- rationally and facilitate detection and lated circumstances. Results: These in- treatment of parental mental conditions cidents accounted for 188 child deaths; might help prevention efforts. 69% were under 11 years old, and 58% Key words: homicide-suicide, children were killed with a firearm. Approximately Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(4):531-542 76% of perpetrators were males, and 75% DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.37.4.11 omicide-followed-by-suicide (hereafter re- of homicide-suicide victims are children, stepchil- ferred to as “homicide-suicide”) incidents dren, or foster children of the perpetrator.1 This Hare defined as violent acts during which finding indicates that research is needed to iden- a person kills one or more individuals and then tify factors that might prevent this form of violence commits suicide.1-3 These incidents account for against children from occurring. -

POSTVENTION: a Guide for Response to Suicide on College Campuses

POSTVENTION: A Guide for Response to Suicide on College Campuses A Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA) Project 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS About the Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA) Envisioned and formed in September 2008 under the leadership of the American College Health Association (ACHA), the Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA) is a partnership of organizations dedicated to advancing college mental health. The Alliance affirms that the issue of college mental health is central to student success, and therefore, is the responsibility of higher education. The following individuals provided valuable input and oversight on the creation of this guide. The American College Counseling Association (ACCA) The American Psychological Association (APA)/ Kathryn P. (Tina) Alessandria, PhD, LPCMH, ACS Society of Counseling Psychology (SCP) Associate Professor, Department of Counselor Education, Traci E. Callandrillo, PhD West Chester University Assistant Director for Clinical Services, Counseling Center, American University Monica Osburn, PhD Director, Counseling Center, NC State University The American Psychiatric Association (APA) The American College Personnel Association (ACPA) Leigh White, MD Chief, Psychiatry Services, Michigan State University Melissa Bartsch, PhD Student Health Assistant Director/Director of Training, University of Tennessee-Knoxville Eric Klingensmith, PsyD The Association for University and College Counseling Assistant Director, Grand Valley State University Center Directors (AUCCCD) Counseling -

Werther's Syndrome: Copycat Self-Immolation in Israel with a Call

IMAJ • VOL 14 • JuLy 2012 FOCUS Werther’s Syndrome: Copycat Self-Immolation in Israel with a Call for Responsible Media Response Benjamin Greenberg MD1 and Rael D. Strous MD1,2 1Department of Psychiatry, Beer Yaakov Mental Health Center, Beer Yaakov, Israel 2Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel throughout the Arab world and became person... fighting to the end... a soldier self-immolation, suicide, copycat KEY WORDS: known as the “Arab Spring.” who fell in battle, in contrast to the weak behavior, Werther’s syndrome Bouazizi’s act received massive media ones, who deteriorate to poverty” [7]. IMAJ 2012; 14: 467-469 coverage worldwide. He was hailed by Media coverage of suicide acts has Arab commentators as a “hero” and been found to be significantly related a “martyr,” and his act was reported to an increase in the rates of copycat extensively in the western media as suicide. This phenomenon is known elf-immolation is the act of setting well. TIME magazine named Bouazizi as the “Werther effect” [8], alternately S oneself on fire, in the majority of “Person of the Year” for 2011, describing referred to as “Werther’s syndrome.” cases with the intention of committing him as a “martyr who brought the Arab The phenomenon was first elucidated by suicide, while expressing a social or world down to its knees” [4]. David Phillips in 1974 [9] and refers to political protest. The incidence varies Most recently in Israel, Moshe the trend noted throughout Europe in among different cultures, religions and Silman, a 57 year old social activist the 18th century and considered to be social-political climates. -

Preventing Suicide a Resource for Establishing a Crisis Line WHO/MSD/MER/18.4

Preventing suicide A resource for establishing a crisis line WHO/MSD/MER/18.4 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Preventing suicide: a resource for establishing a crisis line. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/MSD/MER/18.4). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. -

Factors Related in Suicide Attempts in Admitted Poisoned Patients

Factors Related in Suicide Attempts in Admitted Poisoned Patients Bita Dadpour1 (MD); Faezeh Madani Sani2 (Medical Student); Mahboubeh Rahimi Doab3 (MSc); Ashraf Gerami4 (BSc); Parisa Rajaei5 (MSc); Mahdi Talebi6* (MD) 1. Addiction Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 2. Medical Toxicology Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad ,Iran. 3. Cardiac Anesthesia Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 4. Addiction Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 5. Eye Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 6. Department of Family Medicine, Addiction Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article type: Introduction Suicide is considered as a public health problem. Original Article Approximately 0.9% of all deaths worldwide are due to suicide. This study was performed to identify risk factors of suicide attempts among patients who Article history: admitted in a medical toxicology centre during three months. Received: 22-Apr-2015 Materials and Methods: A cross sectional study was carried out; all Accepted: 13-May-2015 admitted patients in our medical toxicology centre due to suicidal attempt who completed consent form were included from December to March 2013. A Keywords: researcher designed questionnaire was prepared and its validity and reliability Risk factor was confirmed; it was fulfilled by a psychologist via clinical interview. Data Suicide were analyzed by SPSS software 11.5 and results were discussed. Poisoning Results: 198 participants included; of whom 67.2% were female and 94.9% were less than 45 year old.