Preventing Suicide a Resource for Establishing a Crisis Line WHO/MSD/MER/18.4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Suicide Prevention and Postvention Toolkit for Texas Communities

Coming Together to Care Together Coming gethe To r t g o n i C a m r o e C A Suicide Prevention and Postvention Toolkit for Texas Communities Texas Suicide Prevention Council Texas Youth Suicide Prevention Project Virtual Hope Box App (coming soon) The Virtual Hope Box app will provide an electronic version of the Hope Box concept: a place to store important images, notes, memories, and resources to promote mental wellness. The app will be free for teens and young adults, and available for both Android and iPhone users. For up-to-date information on the Virtual Hope Box, please see: http://www.TexasSuicidePrevention.org or http://www.mhatexas.org. ASK & Prevent Suicide App (now available) ASK & Prevent Suicide is a suicide prevention smartphone app for Android and iPhone users. suicide, crisis line contact information, and other resources. To download this app, search “suicide preventionThis free app ASK” is filled in iTunes with oruseful Google information Play. about warning signs, guidance on how to ask about True Stories of Hope and Help (videos online now) A series of short videos featuring youth and young adults from Texas sharing their stories of hope and help. These are true stories of high school and college age students who have either reached out for help or referred a friend for help. These videos can be found at: http://www. TexasSuicidePrevention.org or on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/user/mhatexas). FREE At-Risk Online Training for Public Schools and Colleges (now available) Watch for the middle school training scheduled for release in the fall of 2012. -

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan Written by DeQuincy A. Lezine, PhD and Noah J. Whitaker, MBA For those who struggle, those who have been lost, those left behind, may you find hope… Fresno Cares 2018 Introduction 4 Background and Rationale 5 How Suicide Impacts Fresno County 5 The Fresno County Suicide Prevention Collaborative 7 History 8 Capacity-Building 9 Suicide Prevention in Schools (AB 2246) 10 Workgroups 10 Data 11 Communication 11 Learning & Education 12 Health Care 13 Schools 14 Justice & First Responders 15 Understanding Suicide 16 Overview: the Suicidal crisis within life context 17 The Suicidal Crisis: Timeline of suicidal crisis and prevention 22 Levels of Influence: The Social-Ecological Model 23 Identifying and Characterizing Risk 24 Understanding How Risk Escalates Into Suicidal Thinking 26 Warning Signs: Recognizing when someone may be suicidal 27 Understanding How Suicidal Thinking Turns into Behavior 28 Understanding How a Suicide Attempt Becomes a Suicide 28 Understanding How Suicide Affects Personal Connections 29 Stopping the Crisis Path 30 Comprehensive Suicide Prevention in Fresno County 31 Health and Wellness Promotion 34 Prevention (Universal strategies) 34 Early Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Clinical Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Crisis Intervention and Postvention (Indicated strategies) 36 Where We are Now: Needs and Assets in Fresno County 37 Suicidal Thoughts and Feelings 37 Suicide Attempts 40 1 Suicide 41 Understanding -

Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention

2018 Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention A STUDY OF YOUTH SUICIDE IN FOUR COLORADO COUNTIES Presented to Attorney General Cynthia H. Coffman Colorado Office of the Attorney General By Health Management Associates 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary..............................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................11 Scope of the Problem........................................................................................................................................................11 Key Stakeholder Interviews...........................................................................................................................................13 Community Focus Groups.............................................................................................................................................. 17 School Policies & Procedures........................................................................................................................................27 Traditional Media & Suicide.......................................................................................................................................... -

Answer Key: Suicide Prevention

Personal Health Series Suicide Quiz Answer Key 1. List four factors that can increase a teen’s risk of suicide: Any four of the following: a psychological disorder, especially depression, bipolar disorder, and alcohol and/or drug use; feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness; previous suicide attempt; family history of depression or suicide; emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; lack of a support network, poor relationships with parents or peers, and feelings of social isolation; dealing with bisexuality or homosexuality in an unsupportive family or community or hostile school environment; perfectionism. 2. True or false: If a person talks about suicide, it means he or she is just looking for attention and won’t go through with it. 3. True or false: The danger of suicide has passed when a person begins to cheer up. 4. List four warning signs that someone is thinking about suicide: Any four of the following: talking about suicide or death in general; hinting he/she might not be around anymore; talking about feeling hopeless or feeling guilty; pulling away from friends or family; writing songs, poems, or letters about death, separation, or loss; giving away treasured possessions; losing the desire to do favorite things or activities; having trouble concentrating or thinking clearly; changing eating or sleeping habits; engaging in risky or self-destructive behaviors; losing interest in school and/or extra-curricular activities. 5. True or false: Once a person is suicidal, he or she is suicidal forever. 6. True or false: Most teens who attempt suicide really intend to die. 7. True or false: If a friend tells you she’s considering suicide and swears you to secrecy, you have to keep your promise. -

Healthcare Inspection

Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General Healthcare Inspection Service Delivery and Follow-up After a Patient’s Suicide Attempt Minneapolis VA Health Care System Minneapolis, Minnesota Report No. 12-01760-230 July 19, 2012 VA Office of Inspector General Washington, DC 20420 To Report Suspected Wrongdoing in VA Programs and Operations: Telephone: 1-800-488-8244 E-Mail: [email protected] (Hotline Information: http://www.va.gov/oig/hotline/default.asp) Service Delivery and Follow-up After a Patient’s Suicide Attempt, Minneapolis VA HCS, Minneapolis, MN Executive Summary The VA Office of Inspector General Office of Healthcare Inspections conducted a review at the request of Congressman Tim Walz regarding alleged improper medication management and discharge planning practices at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (the facility) in Minneapolis, MN. We did not substantiate the complainant’s allegations that a change in medication contributed to her husband’s death by suicide, that managers improperly tried to “commit” him to a Veterans Home, or that staff told her she was not her husband’s power of attorney (POA). Medical record documentation reflects that the patient’s medication had not been changed. His chronic depression was attributed to his medical and mental health conditions and to his substantial psychosocial stressors. Further, the medical record does not support the allegations related to the Veterans Home or POA. We found, however, that the Suicide Prevention Coordinator did not participate in the evaluation and ongoing monitoring of the patient, and the treatment team did not complete a suicide risk assessment at the time of the patient’s discharge in February. -

Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative

PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Preventing suicide: a global imperative. 1.Suicide, Attempted. 2.Suicide - prevention and control. 3.Suicidal Ideation. 4.National Health Programs. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 156477 9 (NLM classification: HV 6545) © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility The designations employed and the presentation of the material in for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning arising from its use. -

TFG 2018 Global Report

Twitter Public Policy #TwitterForGood 2018 Global Report Welcome, Twitter’s second #TwitterForGood Annual Report reflects the growing and compelling impact that Twitter and our global network of community partners had in 2018. Our corporate philanthropy mission is to reflect and augment the positive power of our platform. We perform our philanthropic work through active civic engagement, employee volunteerism, charitable contributions, and in-kind donations, such as through our #DataForGood and #AdsForGood programs. In these ways, Twitter seeks to foster greater understanding, equality, and opportunity in the communities where we operate. Employee Charity Matching Program This past year, we broke new ground by implementing our Employee Charity Matching Program. This program avails Twitter employees of the opportunity to support our #TwitterForGood work by matching donations they make to our charity partners around the world. After it was launched in August 2018, Twitter employees donated US$195K to 189 charities around the world. We look forward to expanding this new program in 2019 by garnering greater employee participation and including additional eligible charities. @NeighborNest This year, our signature philanthropic initiative – our community tech lab called the @NeighborNest – was recognized by the Mutual of America Foundation. The Foundation awarded Twitter and Compass Family Services, one of our local community partners, with the 2018 Community Partnership Award. This is one of the top philanthropic awards in the U.S., recognizing community impact by an NGO/private sector partnership. Since opening in 2015, we’ve conducted over 4,000 hours of programming and welcomed over 15,000 visits from the community. This was made possible in partnership with over 10 key nonprofit partners, nearly 900 unique visits from Twitter volunteers, and over 1,400 hours of volunteer service. -

Crisis, Emergency, and Information Services Updated: 1/6/2020

Crisis, Emergency, and Information Services Updated: 1/6/2020 Emergency Crisis Response Call or Text 911 *Ask for CIT (crisis intervention trained) officer to help persons with mental disorders and/or addictions access medical treatment rather than place them in the criminal justice system due to illness related behaviors. Champaign County Crisis Line…………………………………………………………….……………….…. (217)-359-4141 24-hour suicide prevention and crisis hotline for the Champaign County, Illinois area. SASS (Screening, Assessment, and Support Services) ………………………………….......….…1-800-345-9049 A crisis mental health service program for children and adolescents, who are experiencing a psychiatric emergency. 2-1-1 United Way……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 211 24-free phone line to help the public find needed services in the community. Website: www.unitedwayillinois.org/211/211.php and www.navigateresources.net/path/ American Red Cross………………………………………………………………………………………………………… (217)-351-5861 Location: 404 Ginger Bend Drive, Champaign. Services for those affected by natural disasters and single family fires. Website: www.redcrossillinois.org Child Abuse Hotline (DCFS)………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1-800-252-2873 24-hour hotline to report suspected child abuse/neglect. Crisis Nursery………………………………………………………………………………………………… (217)-337-2730 (crisis line) Location: 1309 W. Hill St., Urbana. Free 24-hour emergency child care for families with children, up to age 5. Staff speak Spanish. Website: www.crisisnursery.net DCFS – Illinois Department of Children and Family Services…………………………..…………….. (217)-278-5400 Location: 508 S. Race Street, Urbana Housing assistance, parent education, and family support. Disaster Distress Line…………………………………………………………………….………… 1-800-985-5990 or Text 66746 Spanish: 1-800-985-5990, press 2 Provides 24/7, 365-day-a-year crisis counseling and support to people experiencing emotional distress related to natural or human-caused disasters. -

National Guidelines: Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide

Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force April 2015 Blank page Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Table of Contents Front Matter Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... i Task Force Co-Leads, Members .................................................................................................................. ii Reviewers .................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... iii National Guidelines Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Terminology: “Postvention” and “Loss Survivor” ....................................................................................... 4 Development and Purpose of the Guidelines ............................................................................................. 6 Audience of the Guidelines ........................................................................................................................ -

Comments to FCC Secretary On

March 23, 2021 Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communication Commission 45 L Street NE Washington, DC 20554 Re: Ex Parte Docket No. 18-336; Docket No. 20-291; Docket No. 09-14 Dear Ms. Dortch, The undersigned organizations, all of whom support the development and implementation of the 988 national mental health and suicide crisis response system, are deeply appreciative of the Commission’s role in creating 988 and your current efforts to address fee diversion. The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, unanimously passed by both chambers of Congress and signed into law last year, designates the collection and use of 911-like fees to support 988 call centers, crisis outreach, and stabilization—the continuum of crisis care needed to appropriately respond to callers in distress. 988 service fees, like 911 service fees, will provide a stable, continued source of funding for the hundreds of under-resourced local crisis call centers that will answer 988 calls in communities across the country. An effective 988 crisis response system has never been more necessary. Before the outset of COVID-19, nearly 1 in 5 people lived with a mental health condition and over 10 million people experienced thoughts of suicide. Recent reporting from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that mental health and suicidal ideation have worsened during the pandemic; approximately twice as many respondents reported serious thoughts of suicide and 40% of U.S. adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use. Present-day stressors can be particularly challenging for at-risk communities, with nearly 1 in 4 young people reporting suicidal thoughts. -

Certified Centers Addresses

Name of Center City State Zip Website 180 Turning Lives Around, 2nd Floor Haziet NJ 7735 www.180nj.org 2-1-1 Big Bend, Inc. Tallahassee FL 32302 www.211bigbend.org 211 Brevard Cocoa FL 32923-0417 www.211brevard.org 211 Broward Oakland Park FL 33334 www.211-broward.org 211 Palm Beach/Treasure Coast Lantana FL 33462 www.211palmbeach.org 2-1-1 Tampa Bay Cares Largo FL 33779 www.211tampabay.org Access Helpline Washington DC 20002 www.dbh.dc.gov/service/access-helpline ACTS/Helpline Manassas VA 22026 www.actspwc.org/acts-programs/helpline/ ADAPT Community Solutions Dallas TX 75207 www.adaptusa.com Alachua County Crisis Center Gainesville FL 32641 www.alachuacounty.us/crisis Austin Travis County Integral Care Austin TX 78764 www.atcic.org Avail Solutions Inc Corpus Christi, TX 78411 www.availsolutions.com Baltimore Crisis Response, Inc. Baltimore MD 21239 www.bcresponse.org Behavioral Health Response St. Louis MO 63141 www.bhrstl.org Boys Town National Hotline Omaha NE 68010 www.boystown.org Canadian Mental Health Association: Edmonton Region Edmonton AB Canada T5J 1G4 www.edmonton.cmha.ca Canandaigua Veterans Affairs Medical Center, National Veterans' Suicide Hotline Canandaigua NY 14424 www.canandaigua.va.gov Careline Crisis Intervention Fairbanks AK 99701 www.carelinealaska.com Casa Pacifica,Centers for Children & Families Camarillo CA 9012 www.casapacifica.org Cascade Centers, Inc Portland OR 97223 www.cascadecenters.com Center for Elderly Suicide Prevention & Grief Related Service(Institute of Aging) San Francisco CA 94118 http://www.programsforelderly.com/health-center-for-elderly-suicide-prevention.php -

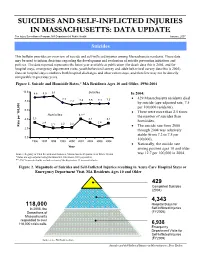

Suicides and Self-Inflicted Injuries in Massachusetts: Data Update

SSUUIICCIIDDEESS AANNDD SSEELLFF--IINNFFLLIICCTTEEDD IINNJJUURRIIEESS IINN MMAASSSSAACCHHUUSSEETTTTSS:: DDAATTAA UUPPDDAATTEE The Injury Surveillance Program, MA Department of Public Health January, 2007 Suicides This bulletin provides an overview of suicide and self-inflicted injuries among Massachusetts residents. These data may be used to inform decisions regarding the development and evaluation of suicide prevention initiatives and policies. The data reported represents the latest year available at publication (for death data this is 2004, and for hospital stays, emergency department visits, youth behavioral survey and adult behavioral survey data this is 2005). Data on hospital stays combines both hospital discharges and observation stays, and therefore may not be directly comparable to previous years. Figure 1. Suicide and Homicide Rates,* MA Residents Ages 10 and Older, 1996-2004 10.0 8.8 8.9 9.1 Suicides In 2004: 7.7 • 429 Massachusetts residents died 8.0 7.2 7.4 7.5 7.4 7.5 by suicide (age-adjusted rate, 7.5 per 100,000 residents). 6.0 • There were more than 2.5 times Homicides 4.1** the number of suicides than 4.0 3.3 3.2 3.1 2.4 2.4 homicides. 2.1 2.2 2.2 100,000 per Rate • The suicide rate from 2000 2.0 through 2004 was relatively stable (from 7.2 to 7.5 per 0.0 100,000). 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 • Nationally, the suicide rate Year among persons ages 10 and older Source: Registry of Vital Records and Statistics, Massachusetts Department of Public Health was 12.7 per 100,000 in 2004.