Table of Contents Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura Final EIA Report Prepared for: Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited Prepared by: SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. June, 2016 EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari FINAL REPORT EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura M/s Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited For on and behalf of SENES Consultants India Ltd Approved by Mr. Mangesh Dakhore Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date 28.12.2015 Approved by Mr. Sunil Gupta Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date February 2016 The EIA report preparation have been undertaken in compliance with the ToR issued by MoEF vide letter no. J-11011/248/2013-IA II (I) dated 28th January, 2014. Information and content provided in the report is factually correct for the purpose and objective for such study undertaken. SENES/M-ESM-20241/June, 2016 i JOGPL EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari INFORMATION ABOUT EIA CONSULTANTS Brief Company Profile This Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report has been prepared by SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. SENES India, registered with the Companies Act of 1956 (Ranked No. 1 in 1956), has been operating in the county for more than 11 years and holds expertise in conducting Environmental Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments, Environment Health and Safety Compliance Audits, Designing and Planning of Solid Waste Management Facilities and Carbon Advisory Services. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

International Journal of Life Science and Pharma Research Indigenous

ijlpr 2021; doi 10.22376/ijpbs/lpr.2021.11.3.L17-22 International Journal of Life science and Pharma Research Botany for Medicinal science Research Article Indigenous Medicinal Plants of Tripura used by the Folklore Practitioners for the Treatment of Bone Fractures Gunamoni Das1*, Anjan Kumar Sarma2, NitulJyoti Das3, Prasenjit Bhagawati4And R. K. Sharma5 1,2,3,4Assam down town University, Panikhaiti, Guwahati-781068, Assam, India 5Government Ayurvedic College & Hospital, Jalukbari, Guwahati- 781014, Assam, India Abstract: Traditional medicine is the oldest form of medicine and modern medicine has its roots in it. The experienced folklore practitioners are very scientific in their approach and understand well the mind and body relationship. This has enabled them to treat their patients in an integrated and holistic manner. Indian system of medicine has identified around medicinal plants, of which 500 species are used in preparation of drug formulations. KiratDesh an ancient name of Tripura was well known as a land of hills and dates in the past and was very rich in flora and fauna diversity. Almost all the plants contain some chemical compounds that are beneficial to mankind and many of them are used for medicinal values. In Tripura, about 266 species have been found to have medicinal properties. Folklore practitioners of Tripura were studied for the use of indigenous medicinal plants in the treatment of bone fractures. They use a combination of herbal, physical and natural process for treatment. They know that natural resources that have nurtured the human race the secret of healing. Knowledge of Traditional medicine is like a family heirloom and is transferred by means of inheritance. -

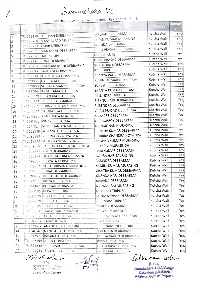

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

2021081046.Pdf

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

Udaipur Centre

List of provisionally eligible candidates for Tripura Civil Service Grade-II and Tripura Police Service Grade-II. Group-A Gazetted , vide Advt-02/2019 dated 6.3.19 for Udaipur Centre. Physically Sl No Candidate's Name Father's Name Category Challenged 1 SUJAN CHAKRABORTY RAMESWAR CHAKRABORTY UR No 2 KAUSHIK MAJUMDER KIRAN MAJUMDER UR No 3 ASHIM MAJUMDER ASHUTOSH MAJUMDER UR No 4 RUPAK DEY DILIP DEY UR No 5 ARUNA RANI DEBBARMA CHAMPA MANIK DEBBARMA ST No 6 INDRA KUMARI JAMATIA MAHESH CHANDRA JAMATIA ST No 7 SANTANU SEN GAURANGA SEN UR No 8 KISHORE JAMATIA BIPAD SADHAN JAMATIA ST No 9 DEBABRATA NATH DULAL CHANDRA NATH OBC No 10 RITA SAHA MANINDRA KUMAR SAHA UR No 11 SAGARIKA ROY DULAL ROY UR No 12 TAPASH PAUL LT DULAL CH PAUL UR No 13 HIMADRI CHAKRABORTY SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY UR No 14 RAHUL DATTA SUDHIR DATTA OBC No 15 ABHI JAMATIA TARANI KANTA JAMATIA ST No 16 PARTHA PRATIM BHATTACHARJEE RANJAN BHATTACHARJEE UR No 17 SUJIT DATTA ASHUTOSH DATTA UR No 18 SATYAJIT MAJUMDER JIBAN CHANDRA MAJUMDER SC No 19 ALAKESH DEBNATH HARADHAN DEBNATH UR No 20 SUMAN MITRA DULAL CHANDRA MITRA SC No 21 MANISH DEBNATH MANORANJAN DEBNATH OBC No 22 DEBABRATA MAJUMDER DULAL MAJUMDER UR No 23 ADESH MIA SARKAR LT NIRAJ MIA SARKAR UR No 24 AJOY BHADURI LT. RATNESWAR BHADURI UR No 25 JHARNA BEGAM AZIZULLA KAZI UR No 26 BIKRAM MITRA RABINDRA MITRA UR No 27 NIVEDITA MAJUMDER PRADIP MAJUMDER UR No 28 PRITAM KUMAR DAS BIJAN BIHARI DAS SC No 29 RUPAK SARKAR SHIBAPRASAD SARKAR UR No 30 BABLU KISHORE SEN SWAPAN PRASAD SEN UR No 31 RAHUL BHOWMIK SUKESH CHANDRA BHOWMIK OBC No -

Portrait of Population, Tripura

CENS US OF INDIA 1971 TRIPURA a portrait of pop u I a t ion A. K. BHATTACHARYYA 0/ the Tripura Civil Service Director of Census 'Operations TRIPURA Crafty mEn condemn studies and principles thereof Simple men admire them; and wise men use them. FRANCIS BACON ( i ) CONTENTS FOREWORD PREFACE ix CHAPTER I INTRODUcrORY Meaning of Cemu;-Historical perspective-Utility of Census-Historical background and Gazetteer of the State Planning of Census-Housing Census-Census-ta1<ing Organisa- tion and Machinery 1-105 II HOW MANY ARE WE? HOW ARE WE DISTRIBUTED AND BY HOW MUCH ARE OUR NUMBERS GROWING f Demography, the science of population-Population growth and its components-Sex and age composition-Sex ratio Distribution of age in Census data--Life Table from Census age data-A few refined measures of fertility-Decadal growth rates for Indian States-Size of India's population in contrast to some other countries-Size and distribution of population of Tripura in comparison with other States-Density of popula tion-Residential Houses and Size of household--Asian popula tion-findings of ECAFE Study-Growth rate of population in Tripura-Role of Migration in the Growth of population in Tripura 16-56 UI VILLAGE DWELLERS AND TOWN DWELLERS Growth story of village and town-Relationship among the dwellers of Tripura--Cultivable area available in Tripura Criteria for distinguishing Urban and Rural in different countries and in India-Distinction between vill.lge community and city community-Distribution of villages in Tripura-Level of urbanisation in Tripura-Concept of Standard Urban Area (SUA)-Urban Agglomeration. -

College of Post Graduate Studies in Agricultural Sciences, Barapani, Meghalaya

COLLEGE OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES IN AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES, BARAPANI, MEGHALAYA M.Sc Theses NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT (NRM) S. Title of the thesis Name of Major Year of Outcome (2-3 lines) No the subject completio . student n 1. Rice Discipline: Agronomy Classification/category: Agrotechniques 1 Evaluation of rice cultivars Mr. K. Agronom 2013 The hybrid cultivar Arize 6444 gave under various planting Lenin y significantly higher yield over the geometry in mid altitude Singh recommended inbred Shahsarang1 and lowland condition of local cultivar Mynri at all the planting Meghalaya geometries. For getting maximum net return, Arize 6444 should be transplanted at 20 cm x 20 cm planting geometry. 2 Agronomic evaluation of L.Platini Agronom 2018 Under delayed transplanting, rice cultivar rice cultivars under delay Singh y CAU R3 gave significantly high yield and transplanting in the mid economic return on all three transplanting hills of Meghalaya dates CAU R1 could be used as an alternative only upto 5th August transplanting 2. Maize 3 Performance of quality Mr. Agrono 2012 Utilizing the inter space in between the protein maize under Samborlan my maize rows for green manuring with cowpea integrated nutrient g K. helped in improving yield and soil fertility. management practices Waniang Application of 75% RDF in presence of 5 t FYM ha-1 found to increase yield and economics of quality protein maize under mid hill altitudes of Meghalaya. 4 Effect of sources and levels Ms. K. Agrono 2013 Significantly superior cob yield and net of nitrogen on performance Surjarani my return was obtained with nitrogen of sweet corn (Zea mays application of 120 kg ha -1. -

Language Wing

LANGUAGE WING UNDER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT TRIPURA TRIBAL AREAS AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL KHUMULWNG, TRIPURA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PROMOTION OF KOKBOROK AND OTHER TRIBAL LANGUAGES IN TTAADC The Language Wing under Education Department in TTAADC was started in 1994 by placing a Linguistic Officer. A humble start for development of Kokborok had taken place from that particular day. Later, activities has been extended to other tribal languages. All the activities of the Language Wing are decided by the KOKBOROK LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE (KLDC) chaired by the Hon’ble Executive Member for Education Department in TTAADC. There are 12(twelve) members in the Committee excluding Chairman and Member- Secretary. The members of the Committee are noted Kokborok Writers, Poets, Novelist and Social Workers. The present members of the KLDC ar:; Sl. No. Name of the Members and full address 01. Mg. Radha Charan Debbarma, Chairman Hon’ble Executive Member, Education, TTAADC 02. Mg. Rabindra Kishore Debbarma, Member Pragati Bidya Bhavan, Agartala 03. Mg. Shyamlal Debbarma, Member MDC, TTAADC, Khumulwng 04. Mg. Bodhrai Debbarma, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 05. Mg. Chandra Kanta Murasingh, Member Ujan Abhoynagar, Agartala 06. Mg. Upendra Rupini, Member Brigudas Kami, Champaknagar, West Tripura 07. Mg. Laxmidhan Murasing, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 08. Mg. Narendra Debbarma, Member SCERT, Agartala 09. Mg. Chitta Ranjan Jamatia, Member Ex. HM, Killa, Udaipur, South Tripura 10. Mg. Gitya Kumar Reang, Member Kailashashar, North Tripura 11. Mg. Rebati Tripura, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 12. Mg. Ajit Debbarma, Member ICAT Department, Agartala 13. Mg. Sachin Koloi, Member Kendraicharra SB School, Takarjala 14. Mr. Binoy Debbarma, Member-Secretary Senior Linguistic Officer, Education Department There is another committee separately constituted for the development of Chakma Language namely CHAKMA LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE with the following members: Sl No Name of the members and full address 01. -

Udaipur Centre)

LIST OF PROVISIONAL ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES APPLIED AGAINST ADVT. NO.03/2020 DATED 04-03-2020 FOR THE POST OF TCS, GRADE-II AND TPS, GRADE-II (UDAIPUR CENTRE) Sl. No. Application ID / Number Name Father's Name Category 1 1900000008018700000016 MRINMOY SARMA LT KHOKAN CHANDRA SARMA UR 2 1900000008018700000026 OLIVER UCHOI JORI CHANDRA UCHOI ST 3 1900000008018700000029 SHYAMA PRASAD SINGHA NITAI CHANDRA SINGHA UR 4 1900000008018700000035 BISWAJIT TRIPURA KIRAN TRIPURA ST 5 1900000008018700000037 RAJU DEB LATE KAJAL DEB UR 6 1900000008018700000039 BANA RATNA CHAKMA MITRA KANTI CHAKMA ST 7 1900000008018700000049 SUBHANKAR BHATTACHARJEE SUKANTA BHATTACHARJEE UR SWARNENDU 8 1900000008018700000056 SABARNI BHATTACHARJEE UR BHATTACHARJEE 9 1900000008018700000062 DIPRAJ SAHA MANTOSH SAHA UR 10 1900000008018700000069 CHITRAGUPTA MURASING BIPADHARAN MURASING ST 11 1900000008018700000071 PARTHA SHIL PRADIP SHIL UR 12 1900000008018700000115 SUMAN DEBBARMA PUSHRAI DEBBARMA ST 13 1900000008018700000119 SUKANTA MURASING RATAN BASI MURASING ST 14 1900000008018700000140 RITU DEBBARMA BISWAHARI DEBBARMA ST 15 1900000008018700000152 ELAN SANGMA AKAN SANGMA ST 16 1900000008018700000174 RUPA JAMATIA BISANNA HARI JAMATIA ST 17 1900000008018700000184 DHARMENDRA TRIPURA LANKAMANI TRIPURA ST 18 1900000008018700000186 UJJWALA MOG CHELAFRU MOG ST 19 1900000008018700000194 FARUK KAZI ABUL MIAH KAZI UR 20 1900000008018700000198 HIRANI JAMATIA SUJUGYA JAMATIA ST 21 1900000008018700000212 MINATI TRIPURA HARI MOHAN TRIPURA ST 22 1900000008018700000240 SATHAIONG MOG UGYAJAI MOG ST 23 1900000008018700000254 SATISH CHANDRA TRIPURA BANI KANTA TRIPURA ST 24 1900000008018700000265 MINISON MARAK JABUSH MARAK ST 25 1900000008018700000270 Mannish jamatia PABITRA MOHAN JAMATIA ST Page 1 of 45 LIST OF PROVISIONAL ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES APPLIED AGAINST ADVT. NO.03/2020 DATED 04-03-2020 FOR THE POST OF TCS, GRADE-II AND TPS, GRADE-II (UDAIPUR CENTRE) Sl. -

Tripura Board of Joint Entrance Examination - 2014

TRIPURA BOARD OF JOINT ENTRANCE EXAMINATION - 2014 Objection List Sl. No. Form No. Enroll. No. Name of Candidate Category Quota Ground of Objection Center 1 0003 Dipika Mahishya Das Copy of SC certificate of candidate SC 0195 D/o- Birendra Mahishya Das Dharmanagar 2 0016 Aparna Debnath Copy of PRTC of candidate/Father/Mother UR 0228 D/o- Manindra Debnath Dharmanagar 3 0038 Bishal Dhar Copy of PRTC of candidate/Father/Mother UR 0331 S/o- Kirit Bhushan Dhar Dharmanagar 4 0061 Dibakar Dutta Copy of PRTC of Father/Mother UR 0003 S/o- Puspendu Bikash Dutta Dharmanagar 5 0064 Asit Nag Choudhury i. Selection of Group, ii. Column No.12 is filled UR 0172 S/o- Amarendra Nag Choudhury up properly. Dharmanagar 6 0123 Pritam Singh Official designation of father UR DL-072 S/o- Rana Pratab Singh Dharmanagar 7 0130 Biplab Chakrabarty Signature of Candidate on Photograph UR 0270 S/o- Bibhu Ranjan Chakrabarty Dharmanagar 8 0131 Debal Debnath Signature of Candidate on Photograph UR 0036 S/o-Late Dwijendra Debnath Dharmanagar 9 0132 Ranjani Chakma Signature of Father/Mother ST 0151 S/o- Kankan Chakma Dharmanagar 10 0133 Pritam Debnath Signature of Candidate UR 0135 S/o- Pramod Kumar Nath Dharmanagar 11 0134 Nabajit Das Copy of H.S. Appearing certificate SC 0265 S/o- Nirmal Kumar Das Dharmanagar 12 0135 Mridul Nath Signature of Candidate on Photograph UR 0074 S/o- Manimoy Nath Dharmanagar 13 0136 Papia Chakma Copy of H.S. Appearing certificate/H.S. ST 0039 D/o- Debapriya Chakma Marksheet Dharmanagar 14 0137 Pritam Ghosh Selection of Group UR 0060 S/o- Satya Gopal Ghosh Dharmanagar 15 0138 Sourob Das Signature of Candidate on Photograph SC 0266 S/o- Manindra Das Dharmanagar 16 0139 Arpita Ghosh Copy of PRTC of candidate/Father/Mother UR 0139 D/o- Ratan Lal Ghosh Dharmanagar 17 0140 Suraj Nath Selection of Group UR 0329 S/o- Dilip Kumar Nath Dharmanagar 18 0146 Fhani Bushan Chakma Signature of Father/Mother ST 0330 S/o- Sukhamangal Chakma Dharmanagar 19 0147 Arnav Debnath Selection of Group UR 0191 S/o- Ajit Debnath Dharmanagar 20 0153 Sukanta Sahajee Copy of H.S. -

3.2 Tripuri, Reang and Jamatia Tribes 3.3 Chakma, Halam and Noatia Tribes 3.4 Other Tribes 3.5 Let Us Sum up 3.6 Further Readings and References

UNIT 3 TRIBES OF TRIPURA Structure 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Tripuri, Reang and Jamatia Tribes 3.3 Chakma, Halam and Noatia Tribes 3.4 Other Tribes 3.5 Let Us Sum Up 3.6 Further Readings and References 3.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit, we shall learn about the tribal communities of Tripura. After introducing the tribal scenario in the State, we shall discuss the geographical location, socio-economic life, beliefs and customs of the major tribes of the State. The unit will also discuss in brief other minor tribes found in the State. By the end of this unit, you should be able to know: Briefly the tribal scenario in the State; The geographical distribution of the tribes in the State; The socio-economic life of the tribes in the State; and The beliefs and customs among the tribes in the State. 3.1 INTRODUCTION Tripura is a small hilly State situated in the north-eastern part of India. During the British rule, the whole geographical area of Tripura was known as Hill Tipperah. It covers an area of 10, 491 sq. km. and is situated between 22º 5’ and 24º 32’ north latitudes and 91º 10’ and 920 21’east longitudes. A land-locked State, Tripura shares international border of 832 kms long with Bangladesh’s district of Comilla on the west, Sylhet district on the north, Noakhalli and Chittagong Hill Tracts on the south and Chittagong Hill Tracts on the east. With mainland India, Tripura is bounded by the Cachar district of Assam on the north-east and the Mizo hills of Mizoram on the east.