Portrait of Population, Tripura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura Final EIA Report Prepared for: Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited Prepared by: SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. June, 2016 EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari FINAL REPORT EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura M/s Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited For on and behalf of SENES Consultants India Ltd Approved by Mr. Mangesh Dakhore Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date 28.12.2015 Approved by Mr. Sunil Gupta Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date February 2016 The EIA report preparation have been undertaken in compliance with the ToR issued by MoEF vide letter no. J-11011/248/2013-IA II (I) dated 28th January, 2014. Information and content provided in the report is factually correct for the purpose and objective for such study undertaken. SENES/M-ESM-20241/June, 2016 i JOGPL EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari INFORMATION ABOUT EIA CONSULTANTS Brief Company Profile This Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report has been prepared by SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. SENES India, registered with the Companies Act of 1956 (Ranked No. 1 in 1956), has been operating in the county for more than 11 years and holds expertise in conducting Environmental Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments, Environment Health and Safety Compliance Audits, Designing and Planning of Solid Waste Management Facilities and Carbon Advisory Services. -

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

Bru-Reang-Final Report 23:5

Devising Pathways for Appropriate Repatriation of Children of Bru-Reang Community Ms. Stuti Kacker (IAS) Chairperson National Commission for Protection of Child Rights The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) emphasizes the principle of universality and inviolability of child rights and recognises the tone of urgency in all the child related policies of the country. It believes that it is only in building a larger atmosphere in favour of protection of children’s rights, that children who are targeted become visible and gain confidence to access their entitlements. Displaced from their native state of Mizoram, Bru community has been staying in the make-shift camps located in North Tripura district since 1997 and they have faced immense hardship over these past two decades. Hence, it becomes imperative for the National Commission of Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) to ensure that the legal and constitutional rights of children of this community are protected. For the same purpose, NCPCR collaborated with QCI to conduct a study to understand the living conditions in the camps of these children and devise a pathway for the repatriation and rehabilitation of Bru-Reang tribe to Mizoram. I would like to thank Quality Council of India for carrying out the study effectively and comprehensively. At the same time, I would like to express my gratitude to Hon’ble Governor of Mizoram Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Nirbhay Sharma, Mr. Mahesh Singla, IPS, Advisor (North-East), Ministry of Home Affairs, Ms. Saumya Gupta, IAS, Director of Education, Delhi Government (Ex. District Magistrate, North Tripura), State Government of Tripura and District Authorities of North Tripura for their support and valuable inputs during the process and making it a success. -

Table of Contents Chapter 1

Table of Contents Chapter 1 ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Origin and Migration ........................................................................................ 2 1.2. Geographical and Demographic distribution ................................................... 3 1.3. Linguistic affiliation........................................................................................... 4 1.4. Dialectal variations ........................................................................................... 7 1.5. Cultural Background and Literary ..................................................................... 8 1.5.1. Literary background .................................................................................... 17 1.6. Data and Methodology ................................................................................... 18 Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................................... 19 Review of Literature .................................................................................................. 19 Chapter 3 ....................................................................................................................... 21 3. Phonemic inventory ............................................................................................. -

Revision Worksheet A. One Sentence Question: 1. Write the Name of Two Ethnic Groups of Hilly Areas. 2. Write the Name of Two

Subject: Bangladesh & Global Studies Day--8 Class: Five Samia Laboni rd 3 Term Syllabus: Date: 14-10-2020, Wednesday Revision Worksheet Chapter- 11: Ethnic Groups in Bangladesh Topic-1: The Garo A. One sentence Question: 1. Write the name of two ethnic groups of hilly areas. 2. Write the name of two ethnic groups in Bangladsh who have martiarchal society. 3. How many years ago did the Garo migrate to Bangladesh? 4. What language do the Garos speak? 5. What is the name of the traditional religion of the Garos? 6. What is the traditional dress of the Garo women? 7. What is ‘Nokmandi’ 8. What is the name of the sun god of the Garo? B. Creative Question: 1. Write 2 names of ethnic groups. What is the name of Garos native language? Write three sentences about their abode. 2. What is the traditional festival of the Garo? Why do they celebrate it? Write 4 sentences about their festivals. (2018) 3. How many years ago did the Garo start living in the country? Which language do they speak in? Write 3 sentences about their housing. (2015) Prepared by: Samia Laboni Class: Five Subject: BGS, Chapter-11 Topic-1,2,3,4,5-- Day-8, Revision Work sheet 4. What is the name of the traditional religion of the Garos? What is the name of their language? Write 3 sentences about their social system. (2015) Answer Sheet-1 A. One Sentence Question Answer: 1) Two ethnic groups of hilly areas are: the Garo and the Khasi. 2) Two ethnic groups in Bangladsh who have martiarchal society are: the Garo and the Khasi. -

2021081046.Pdf

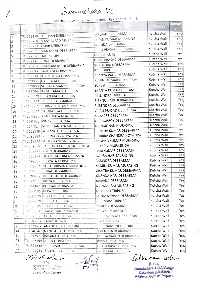

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

Udaipur Centre

List of provisionally eligible candidates for Tripura Civil Service Grade-II and Tripura Police Service Grade-II. Group-A Gazetted , vide Advt-02/2019 dated 6.3.19 for Udaipur Centre. Physically Sl No Candidate's Name Father's Name Category Challenged 1 SUJAN CHAKRABORTY RAMESWAR CHAKRABORTY UR No 2 KAUSHIK MAJUMDER KIRAN MAJUMDER UR No 3 ASHIM MAJUMDER ASHUTOSH MAJUMDER UR No 4 RUPAK DEY DILIP DEY UR No 5 ARUNA RANI DEBBARMA CHAMPA MANIK DEBBARMA ST No 6 INDRA KUMARI JAMATIA MAHESH CHANDRA JAMATIA ST No 7 SANTANU SEN GAURANGA SEN UR No 8 KISHORE JAMATIA BIPAD SADHAN JAMATIA ST No 9 DEBABRATA NATH DULAL CHANDRA NATH OBC No 10 RITA SAHA MANINDRA KUMAR SAHA UR No 11 SAGARIKA ROY DULAL ROY UR No 12 TAPASH PAUL LT DULAL CH PAUL UR No 13 HIMADRI CHAKRABORTY SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY UR No 14 RAHUL DATTA SUDHIR DATTA OBC No 15 ABHI JAMATIA TARANI KANTA JAMATIA ST No 16 PARTHA PRATIM BHATTACHARJEE RANJAN BHATTACHARJEE UR No 17 SUJIT DATTA ASHUTOSH DATTA UR No 18 SATYAJIT MAJUMDER JIBAN CHANDRA MAJUMDER SC No 19 ALAKESH DEBNATH HARADHAN DEBNATH UR No 20 SUMAN MITRA DULAL CHANDRA MITRA SC No 21 MANISH DEBNATH MANORANJAN DEBNATH OBC No 22 DEBABRATA MAJUMDER DULAL MAJUMDER UR No 23 ADESH MIA SARKAR LT NIRAJ MIA SARKAR UR No 24 AJOY BHADURI LT. RATNESWAR BHADURI UR No 25 JHARNA BEGAM AZIZULLA KAZI UR No 26 BIKRAM MITRA RABINDRA MITRA UR No 27 NIVEDITA MAJUMDER PRADIP MAJUMDER UR No 28 PRITAM KUMAR DAS BIJAN BIHARI DAS SC No 29 RUPAK SARKAR SHIBAPRASAD SARKAR UR No 30 BABLU KISHORE SEN SWAPAN PRASAD SEN UR No 31 RAHUL BHOWMIK SUKESH CHANDRA BHOWMIK OBC No -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India's North-East

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India’s North-East: The Case for Re-distributive Justice N.K.Das• Abstract: This paper examines how various brands of identity politics since the colonial days have served to create the basis of exclusion of groups, resulting in various forms of rifts, often envisaged in binary terms: majority-minority; sons of the soil’-immigrants; local-outsiders; tribal-non-tribal; hills-plains; inter-tribal; and intra-tribal. Given the strategic and sensitive border areas, low level of development, immense cultural diversity, and participatory democratic processes, social exclusion has resulted in perceptions of marginalization, deprivation, and identity losses, all adding to the strong basis of brands of separatist movements in the garb of regionalism, sub-nationalism, and ethnic politics, most often verging on extremism and secession. It is argued that local people’s anxiety for preservation of culture and language, often appearing as ‘narcissist self-awareness’, and their demand of autonomy, cannot be seen unilaterally as dysfunctional for a healthy civil society. Their aspirations should be seen rather as prerequisites for distributive justice, which no nation state can neglect. Colonial Impact and genesis of early ethnic consciousness: Northeast India is a politically vital and strategically vulnerable region of India. Surrounded by five countries, it is connected with the rest of India through a narrow, thirty-kilometre corridor. North-East India, then called Assam, is divided into Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. Diversities in terms of Mongoloid ethnic origins, linguistic variation and religious pluralism characterise the region. This ethnic-linguistic-ecological historical heritage characterizes the pervasiveness of the ethnic populations and Tibeto-Burman languages in northeast. -

Language Wing

LANGUAGE WING UNDER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT TRIPURA TRIBAL AREAS AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL KHUMULWNG, TRIPURA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PROMOTION OF KOKBOROK AND OTHER TRIBAL LANGUAGES IN TTAADC The Language Wing under Education Department in TTAADC was started in 1994 by placing a Linguistic Officer. A humble start for development of Kokborok had taken place from that particular day. Later, activities has been extended to other tribal languages. All the activities of the Language Wing are decided by the KOKBOROK LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE (KLDC) chaired by the Hon’ble Executive Member for Education Department in TTAADC. There are 12(twelve) members in the Committee excluding Chairman and Member- Secretary. The members of the Committee are noted Kokborok Writers, Poets, Novelist and Social Workers. The present members of the KLDC ar:; Sl. No. Name of the Members and full address 01. Mg. Radha Charan Debbarma, Chairman Hon’ble Executive Member, Education, TTAADC 02. Mg. Rabindra Kishore Debbarma, Member Pragati Bidya Bhavan, Agartala 03. Mg. Shyamlal Debbarma, Member MDC, TTAADC, Khumulwng 04. Mg. Bodhrai Debbarma, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 05. Mg. Chandra Kanta Murasingh, Member Ujan Abhoynagar, Agartala 06. Mg. Upendra Rupini, Member Brigudas Kami, Champaknagar, West Tripura 07. Mg. Laxmidhan Murasing, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 08. Mg. Narendra Debbarma, Member SCERT, Agartala 09. Mg. Chitta Ranjan Jamatia, Member Ex. HM, Killa, Udaipur, South Tripura 10. Mg. Gitya Kumar Reang, Member Kailashashar, North Tripura 11. Mg. Rebati Tripura, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 12. Mg. Ajit Debbarma, Member ICAT Department, Agartala 13. Mg. Sachin Koloi, Member Kendraicharra SB School, Takarjala 14. Mr. Binoy Debbarma, Member-Secretary Senior Linguistic Officer, Education Department There is another committee separately constituted for the development of Chakma Language namely CHAKMA LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE with the following members: Sl No Name of the members and full address 01. -

Udaipur Centre)

LIST OF PROVISIONAL ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES APPLIED AGAINST ADVT. NO.03/2020 DATED 04-03-2020 FOR THE POST OF TCS, GRADE-II AND TPS, GRADE-II (UDAIPUR CENTRE) Sl. No. Application ID / Number Name Father's Name Category 1 1900000008018700000016 MRINMOY SARMA LT KHOKAN CHANDRA SARMA UR 2 1900000008018700000026 OLIVER UCHOI JORI CHANDRA UCHOI ST 3 1900000008018700000029 SHYAMA PRASAD SINGHA NITAI CHANDRA SINGHA UR 4 1900000008018700000035 BISWAJIT TRIPURA KIRAN TRIPURA ST 5 1900000008018700000037 RAJU DEB LATE KAJAL DEB UR 6 1900000008018700000039 BANA RATNA CHAKMA MITRA KANTI CHAKMA ST 7 1900000008018700000049 SUBHANKAR BHATTACHARJEE SUKANTA BHATTACHARJEE UR SWARNENDU 8 1900000008018700000056 SABARNI BHATTACHARJEE UR BHATTACHARJEE 9 1900000008018700000062 DIPRAJ SAHA MANTOSH SAHA UR 10 1900000008018700000069 CHITRAGUPTA MURASING BIPADHARAN MURASING ST 11 1900000008018700000071 PARTHA SHIL PRADIP SHIL UR 12 1900000008018700000115 SUMAN DEBBARMA PUSHRAI DEBBARMA ST 13 1900000008018700000119 SUKANTA MURASING RATAN BASI MURASING ST 14 1900000008018700000140 RITU DEBBARMA BISWAHARI DEBBARMA ST 15 1900000008018700000152 ELAN SANGMA AKAN SANGMA ST 16 1900000008018700000174 RUPA JAMATIA BISANNA HARI JAMATIA ST 17 1900000008018700000184 DHARMENDRA TRIPURA LANKAMANI TRIPURA ST 18 1900000008018700000186 UJJWALA MOG CHELAFRU MOG ST 19 1900000008018700000194 FARUK KAZI ABUL MIAH KAZI UR 20 1900000008018700000198 HIRANI JAMATIA SUJUGYA JAMATIA ST 21 1900000008018700000212 MINATI TRIPURA HARI MOHAN TRIPURA ST 22 1900000008018700000240 SATHAIONG MOG UGYAJAI MOG ST 23 1900000008018700000254 SATISH CHANDRA TRIPURA BANI KANTA TRIPURA ST 24 1900000008018700000265 MINISON MARAK JABUSH MARAK ST 25 1900000008018700000270 Mannish jamatia PABITRA MOHAN JAMATIA ST Page 1 of 45 LIST OF PROVISIONAL ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES APPLIED AGAINST ADVT. NO.03/2020 DATED 04-03-2020 FOR THE POST OF TCS, GRADE-II AND TPS, GRADE-II (UDAIPUR CENTRE) Sl.