Black Fashion Designers Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

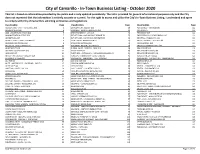

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Techniques of Fashion Earrings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TECHNIQUES OF FASHION EARRINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Deon Delange | 72 pages | 01 Sep 1995 | Eagles View Publishing | 9780943604442 | English | Liberty, Utah, United States Techniques of Fashion Earrings PDF Book These stunning geometric earrings are perfect for a night out on the town or a shopping trip with the girls. And even if you don't go straight over your pencil lines, just kind of go with the flow; let your body feel it as you go. Trends influence what all of us wear to some extent, which is fine. Brendan How to draw human body for fashion design? Do share with us your creations! Two completely different looks, one set of clothe. Spice up some simple silver hoops with this awesome video tutorial for how to make bead earrings. You'll end up losing yourself. My advice? Make a note of the combinations you like if that helps to trigger your memory later. Stringing beads on multiple wires. The days of only wearing one tone of metal is over. When it comes to DIY jewelry, beaded earrings are some of the prettiest patterns out there. As an illustration, one pair of earring contains three hanging flowers: gentle pink, pale purple, and deep purple. Your email address will not be published. Tutorial Features: This beaded Christmas tree pattern will teach you how to make peyote stitch earrings and a peyote stitch necklace. All these bangle styles may be worn in one or each arms relying in your outfit, model and occasion. Eco-friendly jewellery. Try some dangling pearl earrings with a summer print for a fun and flirty look. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Washington, Dc

WASHINGTON, DC BENEFITING CHILDREN'S NATIONAL MEDICAL CENTER Presented by October 1–30, 2016 Washington, DC DCDesignHouse.com EXCLUSIVE DESIGN | SOLID TEAK CONSTRUCTION | LASTING QUALITY Experience the Quality First Hand VISIT OUR SHOWROOM IN GAITHERSBURG, MARYLAND ™ 301.926.9195 www.CountryCasualTeak.com Creating spaces you will love… traditional, modern or somewhere in between.sm Visit ahouckdesigns.com and discover a style that speaks to you. Be inspired today. Andrea Houck, Associate ASID, IFDA | Specializing in Residential Interior Design ahouckdesigns.com | Arlington, Virginia | 703.237.2111 lifestyle boutique Beltway Bethesda-Chevy Chase Landscape Design|Build Center 7405 River Road Bethesda, MD 5258 River Road Bethesda, MD 7405 River Road Bethesda, MD 301.469.7690 301.656.3311 301.762.6301 americanplant.net Congratulations Closets By Design. Recognized as HOME & DESIGN 2016 Designers Choice Award Favorite Custom Closet Company Bob Narod, Photography, LLC Photography, Bob Narod, Custom Closets, Garage Cabinets, Home Offices and more... 703-330-8382 301-880-0866 www.closetsbydesign.com Licensed and Insured 2009 © All Rights Reserved. Closets by Design, Inc. W ASHIN GTON , DC D E S IGN HOUSE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 36/Area 1 Page 47/Area 12 FRONT GARDEN & LOFT PORCH Melanie Hansen, D. Blake Dunlevy Steve Corbeille & Gina Palmer & Pooja Bhagia Mittra D & A Dunlevy Yardstick Interiors Landscapers, Inc. Page 48/Area 13 Page 37/Area 2 VINTAGE CABANA/ ENTRY HALL, HALL, ROOF DECK BACK STAIR HALL Quintece Hill-Mattauszek Eve Fay Studio Q Designs Farrow & Ball Page 49/Area 14 Page 38/Area 3 CHIC RETREAT 31 18 DINING ROOM Barbara Brown Jonathan Senner Barbara Brown Interiors Atelier Jonathan Senner Page 50/Area 15 32 14 Page 39/Area 4 CHIC RETREAT – CHINA PANTRY DRESSING ROOM & Nadia N. -

JEWELLERY TREND REPORT 3 2 NDCJEWELLERY TREND REPORT 2021 Natural Diamonds Are Everlasting

TREND REPORT ew l y 2021 STATEMENT J CUFFS SHOULDER DUSTERS GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY GEOMETRIC DESIGNS PRESENTED BY THE NEW HEIRLOOM CONTENTS 2 THE STYLE COLLECTIVE 4 INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 8 STATEMENT CUFFS IN AN UNPREDICTABLE YEAR, we all learnt to 12 LARGER THAN LIFE fi nd our peace. We seek happiness in the little By Anaita Shroff Adajania things, embark upon meaningful journeys, and hold hope for a sense of stability. This 16 SHOULDER DUSTERS is also why we gravitate towards natural diamonds–strong and enduring, they give us 20 THE STONE AGE reason to celebrate, and allow us to express our love and affection. Mostly, though, they By Sarah Royce-Greensill offer inspiration. 22 GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY Our fi rst-ever Trend Report showcases natural diamonds like you have never seen 26 HIS & HERS before. Yet, they continue to retain their inherent value and appeal, one that ensures By Bibhu Mohapatra they stay relevant for future generations. We put together a Style Collective and had 28 GEOMETRIC DESIGNS numerous conversations—with nuance and perspective, these freewheeling discussions with eight tastemakers made way for the defi nitive jewellery 32 SHAPESHIFTER trends for 2021. That they range from statement cuffs to geometric designs By Katerina Perez only illustrates the versatility of their central stone, the diamond. Natural diamonds have always been at the forefront of fashion, symbolic of 36 THE NEW HEIRLOOM timelessness and emotion. Whether worn as an accessory or an ally, diamonds not only impress but express how we feel and who we are. This report is a 41 THE PRIDE OF BARODA product of love and labour, and I hope it inspires you to wear your personality, By HH Maharani Radhikaraje and most importantly, have fun with jewellery. -

Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture

Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture By Xiaoyu Elena Wang A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wendy L. Brown, Chair Professor Shannon C. Stimson Professor Ramona Naddaff Professor Julia Q. Bryan-Wilson Spring 2015 Abstract Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture by Xiaoyu Elena Wang Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Wendy L. Brown, Chair Every January and June, the most exclusive and influential sector of the global apparel industry stages a series of runway shows in the high fashion, or, couture capitals of New York, Milan, London and Paris. This dissertation explores the production of material goods and cultural ideals in contemporary couture, drawing on scholarly and anecdotal accounts of the business of couture clothes as well as the business of couture models to understand the disquieting success of marketing luxury goods through bodies that appear to signify both extreme wealth and extreme privation. This dissertation argues that the contemporary couture industry idealizes a mode of violence that is unique in couture’s history. The industry’s shift of emphasis toward the mass market in the late 20th-century entailed divestments in the integrity of garment production and modeling employment. Contemporary couture clothes and models are promoted as high-value objects, belying however a material impoverishment that can be read from the models’ physiques and miens. 1 Table of Contents I. The enigma of couture…………………………………………………………………………..1 1. -

HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT of FASHION Phyllis G

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF FASHION Phyllis G. Tortora DOI: 10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10020a Abstract Although the nouns dress and fashion are often used interchangeably, scholars usually define them much more precisely. Based on the definition developed by researchers Joanne Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach Higgins, dress should encompass anything individuals do to modify, add to, enclose, or supplement the body. In some respects dress refers to material things or ways of treating material things, whereas fashion is a social phenomenon. This study, until the late twentieth century, has been undertaken in countries identified as “the West.” As early as the sixteenth century, publishers printed books depicting dress in different parts of the world. Books on historic European and folk dress appeared in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the twentieth century the disciplines of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and some branches of art history began examining dress from their perspectives. The earliest writings about fashion consumption propose the “ trickle-down” theory, taken to explain why fashions change and how markets are created. Fashions, in this view, begin with an elite class adopting styles that are emulated by the less affluent. Western styles from the early Middle Ages seem to support this. Exceptions include Marie Antoinette’s romanticized shepherdess costumes. But any review of popular late-twentieth-century styles also find examples of the “bubbling up” process, such as inner-city African American youth styles. Today, despite the globalization of fashion, Western and non-Western fashion designers incorporate elements of the dress of other cultures into their work. An essential first step in undertaking to trace the history and development of fashion is the clarification and differentiation of terms. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

Fashion Designers' Decision-Making Process

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Fashion designers' decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process Ja-Young Hwang Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Hwang, Ja-Young, "Fashion designers' decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13638. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13638 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fashion designers’ decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process by Ja -Young Hwang A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Apparel, Merchandising, and Design Program of Study Committee: Mary Lynn Damhorst, Co-Major Professor Eulanda Sanders, Co-Major Professor Sara B. Marcketti Cindy Gould Barbara Caldwell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 Copyright © Ja Young Hwang, 2013. All rights -

Décima Temporada 2012 N° 54 - 32 Páginas - Miami, Fl

Décima Temporada 2012 N° 54 - 32 Páginas - Miami, Fl. Publicación Oficial Hispana de los 2 www.deportesyalgomas.com www.deportesyalgomas.com 3 Beisbol 15/18/23 -Somos los Marlins de Miami -“Con el corazón en la mano de rodillas” -Todo lo que debe saber del Estacionamiento del Marlins Park Golf 30 Bubba Ganó el Master Columna 13 OIDO A LA PELOTA Por: Isócrates Arenas Algo Más 20 -Semana Internacional de la Moda: Una sermana fashion, en una ciudad fashión. - Gonzálo Real un cantante de lujo Inaugurada Temporada de las Grandes Ligas 2012 y el nuevo estadio de los Marlins Editorial Boris Mizrahi Comienza una nueva etapa en el deporte que fuera la bujía de la alineación que Weston, Florida del sur de Florida con la inauguración del necesitaban Giancarlo Stanton, Hanley Tel: (954) 217 7762 - (786) 306 6655 Marlins Park precisamente en nuestra déci- Ramírez y compañía. ma temporada como la publicación oficial Se perdieron los dos primeros juegos y Editor en español de los Marlins. quizás lo único negativo de eso en una Boris Mizrahi Un proyecto, que tuvo muchos detractores, temporada tan larga es que en los récords Editor Asociado finalmente es una realidad para el bien de la quedará escrito que los Cardenales Emmanuel Muñoz comunidad a pesar de lo que mucha gente arruinaron el día inaugural del nuevo critique y eso pudimos observarlo desde estadio y que no podrán ganar 162 juegos Directores el día que se comenzó la construcción del en el 2012. Por otro lado, poca gente ha Richard Smith nuevo estadio. dicho que tuvimos que enfrentar al as de Ing. -

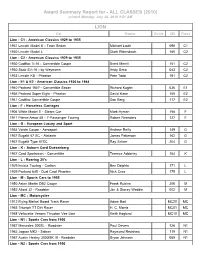

Award Summary Report for - ALL CLASSES (2010) Printed Monday, July 26, 2010 9:51 AM

Award Summary Report for - ALL CLASSES (2010) printed Monday, July 26, 2010 9:51 AM LION Car Owner Circle JID Class Lion - C1 : American Classics 1929 to 1935 1931 Lincoln Model K - Town Sedan Michael Lauth 090 C1 1930 Lincoln Model L Clark Rittersbach 185 C2 Lion - C2 : American Classics 1929 to 1935 1930 Cadillac V-16 - Convertible Coupe Brent Merrill 151 C2 1930 Stutz SV-16 - by Weymann Andy Simo 043 C2 1933 Lincoln KB - Phaeton Pete Todo 181 C2 Lion - E1 & E2 : American Classics 1936 to 1948 1940 Packard 1807 - Convertible Sedan Richard Kughn 036 E1 1936 Packard Super Eight - Phaeton David Kane 155 E2 1941 Cadillac Convertible Coupe Don Berg 117 E2 Lion - F : Horseless Carriages 1904 White Model E - Steam Car Mark Hyman 158 F 1911 Pierce-Arrow 48 - 7-Passenger Touring Robert Reenders 127 F Lion - G : European Luxury and Sport 1934 Voisin Coupe - Aerosport Andrew Reilly 149 G 1937 Bugatti 57 SC - Atalante James Patterson 162 G 1937 Bugatti Type 57SC Ray Scherr 204 G Lion - K : Auburn Cord Duesenberg 1937 Cord Sportsman - Convertible Terence Adderley 154 K Lion - L : Roaring 20's 1929 Invicta Touring - Carlton Ben Delphia 171 L 1929 Packard 645 - Dual Cowl Phaeton Nick Crea 175 L Lion - M : Sports Cars to 1955 1950 Aston Martin DB2 Coupe Frank Rubino 206 M 1952 Allard J2 - Roadster Jim & Stacey Weddle 002 M Lion - MC : Motorcycles 1912 Flying Merkel Board Track Racer Adam Bari MC20 MC 1963 Triumph TT Dirt Racer H. C. Morris MC01 MC 1968 Vellocette Venom Thruxton Vee Line Keith Hoglund MC10 MC Lion - N1 : Sports Cars from 1956 1957 Mercedes 300SL - Roadster Paul Devers 126 N1 1962 Jaguar MK2 - Saloon Raymond Redshaw 119 N1 1967 Austin Healey 3000MK III - Roadster Bryan Johnson 069 N1 Lion - N2 : Sports Cars from 1956 1958 Porsche Speedster Rick Riley 174 N2 1964 Ferrari Berlinetta Lusso - GT Raymond Boniface 120 N2 Lion - O : Celebrity Owned Cars 1942 Packard 180 - Convertible Victoria Richard Kughn 035 O Lion - P1 : American Popular through 1955 1934 Chrysler Airflow - 4-Door Sedan Bill Golling 123 P1 1941 Hudson Super Six - Woodie Wagon Lee N.