ABSTRACT YOU MY HONEYBEE, I'm YOUR FUNKY BUTT by Jeremy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

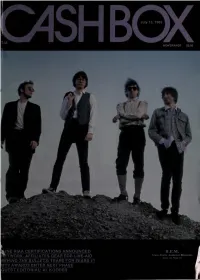

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited by Nicholas Dovellos A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor (Deceased): Martin Schönfeld, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Alex Levine, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Govindan Parayil, Ph.D. Michael Morris, Ph.D. George Philippides, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 7, 2020 Key Words: Climate Ethics, Actionability, Psychoanalysis, Econo-Philosophy, Productive Orientation, Biophilia, Necrophilia, Pathology, Narcissism, Alienation, Interiority Copyright © 2020 Nicholas Dovellos Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Part I: The Current Climate Conversation: Work and Analysis of Contemporary Ethicists ........ 13 Chapter 1: Preliminaries ............................................................................................................ 16 Section I: Cape Town and Totalizing Systems ............................................................... 17 Section II: A Lack in Step Two: Actionability ............................................................... 25 Section III: Gardiner’s Analysis .................................................................................... -

Romantic Comedy-A Critical and Creative Enactment 15Oct19

Romantic comedy: a critical and creative enactment by Toni Leigh Jordan B.Sc., Dip. A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University June, 2019 Table of Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgements iii Dedication iv Exegesis 1 Introduction 2 The Denier 15 Trysts and Turbulence 41 You’ve Got Influences 73 Conclusion 109 Works cited 112 Creative Artefact 123 Addition 124 Fall Girl 177 Our Tiny, Useless Hearts 259 Abstract For this thesis, I have written an exegetic complement to my published novels using innovative methodologies involving parody and fictocriticism to creatively engage with three iconic writers in order to explore issues of genre participation. Despite their different forms and eras, my subjects—the French playwright Molière (1622-1673), the English novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817), and the American screenwriter Nora Ephron (1941-2012)—arguably participate in the romantic comedy genre, and my analysis of their work seeks to reveal both genre mechanics and the nature of sociocultural evaluation. I suggest that Molière did indeed participate in the romantic comedy genre, and it is both gender politics and the high cultural prestige of his work (and the low cultural prestige of romantic comedy) that prevents this classification. I also suggest that popular interpretations of Austen’s work are driven by romanticised analysis (inseparable from popular culture), rather than the values implicit in the work, and that Ephron’s clever and conscious use of postmodern techniques is frequently overlooked. Further, my exegesis shows how parody provides a productive methodology for critically exploring genre, and an appropriate one, given that genre involves repetition—or parody—of conventions and their relationship to form. -

AMIABLE from Safari Club International Conservaticr Fund, 5151 E

ft DOCUMENT Usual Ill 176 905 RC pll 291 AUTHOR Huck, AlbeitP.; 'Decker, Eugene TITLE EnvirdnaentalRespect: A New/Approach to Cutdoor Education. INSTITUTION Safari Club International Conservation fund, Tmosoi, sPos AGENCY Colorado State Univ., Ft. Collins. Dept. of Educat.A.ou.; Colorado State Univ., Et. Collins. Dept. of Fishery and Wildlife Biology. PUB DATE Jan 76 NOTE 174p. AMIABLE FROM Safari Club International Conservaticr Fund, 5151 E. Broadway, Suite 1680, Tncson, Arizona 45711 (S3.50) IDRS PRICE MI01 Plui POstage. PC Not Available from EDES. DESCRIPTORS Activitiesi Animal Behavior; Camping; *Conduct: *Curriculum Development; Curriculum Entichment; Curriculum Planning; Educational Objectives; Educational Philosophy; Educational Resources; *Environaental Education; *Ethical Instruction; Ethics; Experiential Learning;.Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Lesson Plans; *Outdoor Education; *Program Develoiment IDENTIFIERS Fishing; Bunting ABSTRACT most cutdcor education programs do not include the teaching of correct outdoor behavior. The purpose of this manual is to assist educators and concerned lay persons in establishing an outdoor education program with an instructional strategy that will manipulate,students into tecosing responsible, ethical, respectful outdoor citizens. Both lay persons and educators can use the detailed manual explanations,.directions, and hints to guide them through the entire process of designing an Environmental Respect curriculum package, fros°program inception throu9h approval and implementation to valuation and modification. Five sample Curriculus Lesson Ideas (Investigating Wildlife, Investigating Hunting, Investigating Fishing, Investigating Hiking and Camping, and Survival) attempt to bring out the unique qualities of this outdoor education philosophy which mpkasizes developing environmental respect by utilizing the outdoor sports. Respectful behavior is the essence of the units which begin with an introduction and a topic outline. -

1 This Isn't Paradise, This Is Hell: Discourse, Performance and Identity in the Hawai'i Metal Scene a Dissertation Submitte

1 THIS ISN’T PARADISE, THIS IS HELL: DISCOURSE, PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE HAWAI‘I METAL SCENE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2012 By Benjamin Hedge Olson Dissertation Committee: Kathleen Sands, Chairperson David E. Stannard Vernadette Gonzalez Roderick Labrador Helen J. Baroni Keywords: metal, popular music, popular culture, religion, subculture, Hawai‘i 2 Abstract The island of Oahu is home to probably the most ethnically diverse metal scene in the United States. Contemporary Hawai`i prides itself on being a “model of multiculturalism” free of the racism and ethnic strife that is endemic to the continent; however, beneath this superficial openness and tolerance exist deeply felt class, ethnic, and racial tensions. The metal scene in Hawai`i experiences these conflicting impulses towards inclusion and exclusion as profoundly as any other aspect of contemporary Hawaiian culture, but there is a persistent hope within the metal scene that subcultural identity can triumph over such tensions. Complicating this process is the presence of white military personnel, primarily born and raised on the continental United States, whose cultural attitudes, performances of masculinity, and conception of metal culture differ greatly from that of local metalheads. The misunderstandings, hostilities, bids for subcultural capital, and attempted bridge-building that take place between metalheads in Hawai‘i constitute a subculturally specific attempt to address anxieties concerning the presence of the military, the history of race and racism in Hawai`i, and the complicated, often conflicting desires for both openness and exclusivity that exist within local culture. -

Worship Service-As It Was Recently in Fax: 847-742-1407 My Congregation

A nd the Word became flesh and lived among us ... full ef grace and truth. -JOHN 1:14 OuR PRAYER__ FOR YOU THIS CHRISTMAS ... is that in hearing Jesus' story anew you embrace "the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge;' ... that you tell the story to others at home and afar a living witness for Christ in the world, ... that in times of terror and fear you keep alive the vision of peace of the Prince of Peace, ... and that the Word engage and embolden you as an instrument of grace and truth. Church of the Brethren GENERAL BOARD DECEMBER 2001 VOL.150 NO.11 WWW.BRETHREN.ORG Editor: Fletcher Farrar Publisher: Wendy McFadden News: Walt Wiltschek Advertising: Russ Matteson Subscriptions: Verneda Cole Design: Cedar House Group ONTHECOVER 1 O Enduring peace This month's cover is a watercolor As Brethren seek ways of faithfulness in the wake of Sept. 11 attacks by Don Stocksdale of Union City, and retaliation, they move from reaction to action. Brethren Witness Ind. For more than 50 years, he was director David Radcliff outlines ways to pursue God's justice and an active part of the Pleasant Valley peace. Included are inspiring stories of peaceful actions some churches have taken. congregation, in rural western Ohio. He is well-known regionally for his paintings of Midwest landscapes. 18 Christmas in Baghdad This Mideast landscape, however, Mel Lehman, who plans to lead a Church of the Brethren delega was not too much of a stretch for tion to Iraq this month, tells of the suffering he saw on an earlier him. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

A Study of Postmodern Narrative in Akbar Radi's Khanomche and Mahtabi

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 4; September 2012 A Study of Postmodern Narrative in Akbar Radi's Khanomche and Mahtabi Hajar Abbasi Narinabad Address: 43, Jafari Nasab Alley, Hafte-Tir, Karaj, Iran Tel: 00989370931548 E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30-06- 2012 Accepted: 30-08- 2012 Published: 01-09- 2012 doi:10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.4p.245 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.4p.245 Abstract This project aims to explore representation of narratology based on some recent postmodern theories backed up by the ideas of some postmodern discourses including Roland Barthes, Jean-François Lyotard, Julia Kristeva and William James with an especial focus on Akbar Radi-the Persian Playwright- drama Khanomche and Mahtabi .The article begins by providing a terminological view of narrative in general and postmodern narrative in specific. As postmodern narrative elements are too general and the researcher could not cover them all, she has gone through the most eminent elements: intertextuality, stream of consciousness style, fragmentation and representation respectively which are delicately utilized in Khanomche and Mahtabi. The review then critically applies the theories on the mentioned drama. The article concludes by recommending a few directions for the further research. Keywords: Intertextuality, Stream of Consciousness, Fragmentation, Postmodern Reality 1. Introduction Narratologists have tried to define narrative in one way or another; one will define it without difficulty as "the representation of an event or sequence of events"(Genette, 1980, p. 127). In Genette's terminology it refers to the producing narrative action and by extension, the whole of the real or fictional situation in which that action takes place (Ibid. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

FUSSELSCHWARM Full Stock List

FUSSELSCHWARM Full Stock List (as of 01.07.2021 - English Titles only) Contents Page Furplanet 2 – 8 Rabbit Valley 9 – 11 Jarlidium Press 12 United Publications 13 Weasel Press 13 Goal Publications 14 Thurston Howl Pub 15 – 16 Northwest Press 16 – 17 Mixed Publishers 17 – 23 DVDs 23 Card & Board Games 23 Shirts & Puzzles & Plush 23 Non-furry queer titles are in cursive characters. NEW & back in stock tiles and price changes in red. Please order via email: [email protected] FUSSELSCHWARM – Queer Anthropomorphics Volker Wuttke Hansaring 156 24534 Neumuenster Germany General business terms (in German): https://www.fusselschwarm.net/agb Any questions? Contact us via Twitter (DMs are open): @Fusselschwarm via Telegram: @Fusselschwarm via Email: [email protected] Want to be informed about new titles? Follow us on Twitter (@Fusselschwarm) or Telegram (@FusselschwarmInfosEngl) Seite 1 FURPLANET Novels Blaireau, Andre Everybody loves Luther 19,95 € Brown, Fred Don´t go near ther the Sorceress 9,95 € Campbell, Ryan Koa Of The Drowned Kingdom 9,95 € Campbell, Ryan Smiley and the Hero 9,95 € Crowder, Austen The Painted Cat 19,95 € Cross, Malcom Dangerous Jade 9,95 € Darke, Pen Containdications 19,95 € Dragon Cobolt Bucking the System 11,95 € Fahl, D.J. Save the Day 19,95 € Frane, Kevin The Peculiar Quandary of Simon Canopus Artgle 9,95 € Frane, Kevin Summerhill 17,95 € FuzzWolf Trevors Tricks 19,95 € Gibson, Roz Griffin Ranger Vol.2 19,95 € Gold, Kyell Bridges 9,95 € Gold, Kyell Camouflage 19,95 € Gold, Kyell Dude, where´s my Fox? (1) -

The Grizzly, September 21, 1993

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus College Grizzly Newspaper Newspapers 9-21-1993 The Grizzly, September 21, 1993 Jen Diamond Ursinus College Melissa Chido Ursinus College Erika Compton Ursinus College Mark Leiser Ursinus College Craig Faucher Ursinus College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/grizzlynews Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Diamond, Jen; Chido, Melissa; Compton, Erika; Leiser, Mark; Faucher, Craig; Welsh, Jim; Davenport, Amy K.; Cordes, Matt; Epler, Tom; Gil, Victor; Richter, Richard P.; Kozlowski, Tyree; Rychling, Aaron; Rhile, Ian; Fenstermacher, Heidi; Reynolds, Halyna; Baccino, Nick; Rubin, Harley David; and Grunden, Jay, "The Grizzly, September 21, 1993" (1993). Ursinus College Grizzly Newspaper. 318. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/grizzlynews/318 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursinus College Grizzly Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jen Diamond, Melissa Chido, Erika Compton, Mark Leiser, Craig Faucher, Jim Welsh, Amy K. Davenport, Matt Cordes, Tom Epler, Victor Gil, Richard P. Richter, Tyree