Increasing Temperature Increases Disorder, Because the Entropy Dominates the Free Energy at High Temperatures, Whereas Enthalpy Dominates at Low Temperatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

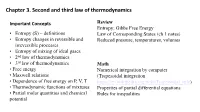

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Thermodynamics

ME346A Introduction to Statistical Mechanics { Wei Cai { Stanford University { Win 2011 Handout 6. Thermodynamics January 26, 2011 Contents 1 Laws of thermodynamics 2 1.1 The zeroth law . .3 1.2 The first law . .4 1.3 The second law . .5 1.3.1 Efficiency of Carnot engine . .5 1.3.2 Alternative statements of the second law . .7 1.4 The third law . .8 2 Mathematics of thermodynamics 9 2.1 Equation of state . .9 2.2 Gibbs-Duhem relation . 11 2.2.1 Homogeneous function . 11 2.2.2 Virial theorem / Euler theorem . 12 2.3 Maxwell relations . 13 2.4 Legendre transform . 15 2.5 Thermodynamic potentials . 16 3 Worked examples 21 3.1 Thermodynamic potentials and Maxwell's relation . 21 3.2 Properties of ideal gas . 24 3.3 Gas expansion . 28 4 Irreversible processes 32 4.1 Entropy and irreversibility . 32 4.2 Variational statement of second law . 32 1 In the 1st lecture, we will discuss the concepts of thermodynamics, namely its 4 laws. The most important concepts are the second law and the notion of Entropy. (reading assignment: Reif x 3.10, 3.11) In the 2nd lecture, We will discuss the mathematics of thermodynamics, i.e. the machinery to make quantitative predictions. We will deal with partial derivatives and Legendre transforms. (reading assignment: Reif x 4.1-4.7, 5.1-5.12) 1 Laws of thermodynamics Thermodynamics is a branch of science connected with the nature of heat and its conver- sion to mechanical, electrical and chemical energy. (The Webster pocket dictionary defines, Thermodynamics: physics of heat.) Historically, it grew out of efforts to construct more efficient heat engines | devices for ex- tracting useful work from expanding hot gases (http://www.answers.com/thermodynamics). -

Muddiest Point – Entropy and Reversible I Am Confused About Entropy and How It Is Different in a Reversible Versus Irreversible Case

1 Muddiest Point { Entropy and Reversible I am confused about entropy and how it is different in a reversible versus irreversible case. Note: Some of the discussion below follows from the previous muddiest points comment on the general idea of a reversible and an irreversible process. You may wish to have a look at that comment before reading this one. Let's talk about entropy first, and then we will consider how \reversible" gets involved. Generally we divide the universe into two parts, a system (what we are studying) and the surrounding (everything else). In the end the total change in the entropy will be the sum of the change in both, dStotal = dSsystem + dSsurrounding: This total change of entropy has only two possibilities: Either there is no spontaneous change (equilibrium) and dStotal = 0, or there is a spontaneous change because we are not at equilibrium, and dStotal > 0. Of course the entropy change of each piece, system or surroundings, can be positive or negative. However, the second law says the sum must be zero or positive. Let's start by thinking about the entropy change in the system and then we will add the entropy change in the surroundings. Entropy change in the system: When you consider the change in entropy for a process you should first consider whether or not you are looking at an isolated system. Start with an isolated system. An isolated system is not able to exchange energy with anything else (the surroundings) via heat or work. Think of surrounding the system with a perfect, rigid insulating blanket. -

Standard Thermodynamic Values

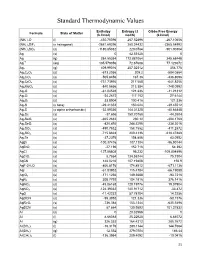

Standard Thermodynamic Values Enthalpy Entropy (J Gibbs Free Energy Formula State of Matter (kJ/mol) mol/K) (kJ/mol) (NH4)2O (l) -430.70096 267.52496 -267.10656 (NH4)2SiF6 (s hexagonal) -2681.69296 280.24432 -2365.54992 (NH4)2SO4 (s) -1180.85032 220.0784 -901.90304 Ag (s) 0 42.55128 0 Ag (g) 284.55384 172.887064 245.68448 Ag+1 (aq) 105.579056 72.67608 77.123672 Ag2 (g) 409.99016 257.02312 358.778 Ag2C2O4 (s) -673.2056 209.2 -584.0864 Ag2CO3 (s) -505.8456 167.36 -436.8096 Ag2CrO4 (s) -731.73976 217.568 -641.8256 Ag2MoO4 (s) -840.5656 213.384 -748.0992 Ag2O (s) -31.04528 121.336 -11.21312 Ag2O2 (s) -24.2672 117.152 27.6144 Ag2O3 (s) 33.8904 100.416 121.336 Ag2S (s beta) -29.41352 150.624 -39.45512 Ag2S (s alpha orthorhombic) -32.59336 144.01328 -40.66848 Ag2Se (s) -37.656 150.70768 -44.3504 Ag2SeO3 (s) -365.2632 230.12 -304.1768 Ag2SeO4 (s) -420.492 248.5296 -334.3016 Ag2SO3 (s) -490.7832 158.1552 -411.2872 Ag2SO4 (s) -715.8824 200.4136 -618.47888 Ag2Te (s) -37.2376 154.808 43.0952 AgBr (s) -100.37416 107.1104 -96.90144 AgBrO3 (s) -27.196 152.716 54.392 AgCl (s) -127.06808 96.232 -109.804896 AgClO2 (s) 8.7864 134.55744 75.7304 AgCN (s) 146.0216 107.19408 156.9 AgF•2H2O (s) -800.8176 174.8912 -671.1136 AgI (s) -61.83952 115.4784 -66.19088 AgIO3 (s) -171.1256 149.3688 -93.7216 AgN3 (s) 308.7792 104.1816 376.1416 AgNO2 (s) -45.06168 128.19776 19.07904 AgNO3 (s) -124.39032 140.91712 -33.472 AgO (s) -11.42232 57.78104 14.2256 AgOCN (s) -95.3952 121.336 -58.1576 AgReO4 (s) -736.384 153.1344 -635.5496 AgSCN (s) 87.864 130.9592 101.37832 Al (s) -

Isothermal Process It Is the Process in Which Other Physical Quantities Might Change but the Temperature of the System Remains Or Is Forced to Remain Constant

Sajit Chandra Shakya Department of Physics Kathmandu Don Bosco College New Baneshwor, Kathmandu Isothermal process It is the process in which other physical quantities might change but the temperature of the system remains or is forced to remain constant. For example, the constant temperature of human body. Under constant temperature, the volume of a gas system is inversely proportional to the pressure applied, the phenomena being called Boyle's Law, written in symbols as 1 V ∝ P 1 Or, V = KB× where KB is a constant quantity. P Or, PV = KB …………….. (i) This means whatever be the values of volume and pressure, their product will be constant. So, P1V1 = KB, P2V2 = KB, P3V3 = KB, etc, Or, P1V1 = P2V2 = P3V3, etc. The requirements for an isothermal process are as follows: 1. The process should be carried very slowly so that there is an ample time for compensation of heat in case of any loss or addition. 2. The boundaries of the system should be highly conducting so that there is a path for heat to flow into or flow away from a closed space in case of any energy loss or oversupply. 3. The boundaries should be made very thin because the resistance of the substance for heat conduction will be less for thin boundaries. Since in an isothermal change, the temperature remains constant, the internal energy also does not change, i.e. dU = 0. So if dQ amount of heat is given to a system which undergoes isothermal change, the relation for the first law of thermodynamics would be dQ = dU + dW Or, dQ = 0 + PdV Or, dQ = PdV This means all the heat supplied will be utilized for performing external work and consequently its value will be very high compared to other processes. -

The First Law of Thermodynamics Continued Pre-Reading: §19.5 Where We Are

Lecture 7 The first law of thermodynamics continued Pre-reading: §19.5 Where we are The pressure p, volume V, and temperature T are related by an equation of state. For an ideal gas, pV = nRT = NkT For an ideal gas, the temperature T is is a direct measure of the average kinetic energy of its 3 3 molecules: KE = nRT = NkT tr 2 2 2 3kT 3RT and vrms = (v )av = = r m r M p Where we are We define the internal energy of a system: UKEPE=+∑∑ interaction Random chaotic between atoms motion & molecules For an ideal gas, f UNkT= 2 i.e. the internal energy depends only on its temperature Where we are By considering adding heat to a fixed volume of an ideal gas, we showed f f Q = Nk∆T = nR∆T 2 2 and so, from the definition of heat capacity Q = nC∆T f we have that C = R for any ideal gas. V 2 Change in internal energy: ∆U = nCV ∆T Heat capacity of an ideal gas Now consider adding heat to an ideal gas at constant pressure. By definition, Q = nCp∆T and W = p∆V = nR∆T So from ∆U = Q W − we get nCV ∆T = nCp∆T nR∆T − or Cp = CV + R It takes greater heat input to raise the temperature of a gas a given amount at constant pressure than constant volume YF §19.4 Ratio of heat capacities Look at the ratio of these heat capacities: we have f C = R V 2 and f + 2 C = C + R = R p V 2 so C p γ = > 1 CV 3 For a monatomic gas, CV = R 3 5 2 so Cp = R + R = R 2 2 C 5 R 5 and γ = p = 2 = =1.67 C 3 R 3 YF §19.4 V 2 Problem An ideal gas is enclosed in a cylinder which has a movable piston. -

Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics

Energy and Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics The internal energy (E) of a system consists of The energy change of a reaction the kinetic energy of all the particles (related to is measured at constant temperature) plus the potential energy of volume (in a bomb interaction between the particles and within the calorimeter). particles (eg bonding). We can only measure the change in energy of the system (units = J or Nm). More conveniently reactions are performed at constant Energy pressure which measures enthalpy change, ∆H. initial state final state ∆H ~ ∆E for most reactions we study. final state initial state ∆H < 0 exothermic reaction Energy "lost" to surroundings Energy "gained" from surroundings ∆H > 0 endothermic reaction < 0 > 0 2 o Enthalpy of formation, fH Hess’s Law o Hess's Law: The heat change in any reaction is the The standard enthalpy of formation, fH , is the change in enthalpy when one mole of a substance is formed from same whether the reaction takes place in one step or its elements under a standard pressure of 1 atm. several steps, i.e. the overall energy change of a reaction is independent of the route taken. The heat of formation of any element in its standard state is defined as zero. o The standard enthalpy of reaction, H , is the sum of the enthalpy of the products minus the sum of the enthalpy of the reactants. Start End o o o H = prod nfH - react nfH 3 4 Example Application – energy foods! Calculate Ho for CH (g) + 2O (g) CO (g) + 2H O(l) Do you get more energy from the metabolism of 1.0 g of sugar or -

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy Dr. John F. C. Turner 409 Buehler Hall [email protected] Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy So far in chemistry 130, and in Chemistry 120, we have described chemical reactions thermodynamically by using U - the change in internal energy, U, which involves heat transferring in or out of the system only or H - the change in enthalpy, H, which involves heat transfers in and out of the system as well as changes in work. U applies at constant volume, where as H applies at constant pressure. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy When chemical systems change, either physically through melting, evaporation, freezing or some other physical process variables (V, P, T) or chemically by reaction variables (ni) they move to a point of equilibrium by either exothermic or endothermic processes. Characterizing the change as exothermic or endothermic does not tell us whether the change is spontaneous or not. Both endothermic and exothermic processes are seen to occur spontaneously. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy Our descriptions of reactions and other chemical changes are on the basis of exothermicity or endothermicity ± whether H is negative or positive H is negative ± exothermic H is positive ± endothermic As a description of changes in heat content and work, these are adequate but they do not describe whether a process is spontaneous or not. There are endothermic processes that are spontaneous ± evaporation of water, the dissolution of ammonium chloride in water, the melting of ice and so on. We need a thermodynamic description of spontaneous processes in order to fully describe a chemical system Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy A spontaneous process is one that takes place without any influence external to the system. -

Lecture 13. Thermodynamic Potentials (Ch

Lecture 13. Thermodynamic Potentials (Ch. 5) So far, we have been using the total internal energy U and, sometimes, the enthalpy H to characterize various macroscopic systems. These functions are called the thermodynamic potentials: all the thermodynamic properties of the system can be found by taking partial derivatives of the TP. For each TP, a set of so-called “natural variables” exists: −= + μ NddVPSdTUd = + + μ NddPVSdTHd Today we’ll introduce the other two thermodynamic potentials: theHelmhotzfree energy F and Gibbs free energy G. Depending on the type of a process, one of these four thermodynamic potentials provides the most convenient description (and is tabulated). All four functions have units of energy. When considering different types of Potential Variables processes, we will be interested in two main U (S,V,N) S, V, N issues: H (S,P,N) S, P, N what determines the stability of a system and how the system evolves towards an F (T,V,N) V, T, N equilibrium; G (T,P,N) P, T, N how much work can be extracted from a system. Diffusive Equilibrium and Chemical Potential For completeness, let’s rcall what we’vee learned about the chemical potential. 1 P μ d U T d= S− P+ μ dVd d= S Nd U +dV d − N T T T The meaning of the partial derivative (∂S/∂N)U,V : let’s fix VA and VB (the membrane’s position is fixed), but U , V , S U , V , S A A A B B B assume that the membrane becomes permeable for gas molecules (exchange of both U and N between the sub- ns ilesystems, the molecuA and B are the same ). -

Thermodynamic Potentials and Thermodynamic Relations In

arXiv:1004.0337 Thermodynamic potentials and Thermodynamic Relations in Nonextensive Thermodynamics Guo Lina, Du Jiulin Department of Physics, School of Science, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China Abstract The generalized Gibbs free energy and enthalpy is derived in the framework of nonextensive thermodynamics by using the so-called physical temperature and the physical pressure. Some thermodynamical relations are studied by considering the difference between the physical temperature and the inverse of Lagrange multiplier. The thermodynamical relation between the heat capacities at a constant volume and at a constant pressure is obtained using the generalized thermodynamical potential, which is found to be different from the traditional one in Gibbs thermodynamics. But, the expressions for the heat capacities using the generalized thermodynamical potentials are unchanged. PACS: 05.70.-a; 05.20.-y; 05.90.+m Keywords: Nonextensive thermodynamics; The generalized thermodynamical relations 1. Introduction In the traditional thermodynamics, there are several fundamental thermodynamic potentials, such as internal energy U , Helmholtz free energy F , enthalpy H , Gibbs free energyG . Each of them is a function of temperature T , pressure P and volume V . They and their thermodynamical relations constitute the basis of classical thermodynamics. Recently, nonextensive thermo-statitstics has attracted significent interests and has obtained wide applications to so many interesting fields, such as astrophysics [2, 1 3], real gases [4], plasma [5], nuclear reactions [6] and so on. Especially, one has been studying the problems whether the thermodynamic potentials and their thermo- dynamic relations in nonextensive thermodynamics are the same as those in the classical thermodynamics [7, 8]. In this paper, under the framework of nonextensive thermodynamics, we study the generalized Gibbs free energy Gq in section 2, the heat capacity at constant volume CVq and heat capacity at constant pressure CPq in section 3, and the generalized enthalpy H q in Sec.4. -

Ch 19. the First Law of Thermodynamics

Ch 19. The First Law of Thermodynamics Liu UCD Phy9B 07 1 19-1. Thermodynamic Systems Thermodynamic system: A system that can interact (and exchange energy) with its surroundings Thermodynamic process: A process in which there are changes in the state of a thermodynamic system Heat Q added to the system Q>0 taken away from the system Q<0 (through conduction, convection, radiation) Work done by the system onto its surroundings W>0 done by the surrounding onto the system W<0 Energy change of the system is Q + (-W) or Q-W Gaining energy: +; Losing energy: - Liu UCD Phy9B 07 2 19-2. Work Done During Volume Changes Area: A Pressure: p Force exerted on the piston: F=pA Infinitesimal work done by system dW=Fdx=pAdx=pdV V Work done in a finite volume change W = final pdV ∫V initial Liu UCD Phy9B 07 3 Graphical View of Work Gas expands Gas compresses Constant p dV>0, W>0 dV<0, W<0 W=p(V2-V1) Liu UCD Phy9B 07 4 19-3. Paths Between Thermodynamic States Path: a series of intermediate states between initial state (p1, V1) and a final state (p2, V2) The path between two states is NOT unique. V2 W= p1(V2-V1) +0 W=0+ p2(V2-V1) W = pdV ∫V 1 Work done by the system is path-dependent. Liu UCD Phy9B 07 5 Path Dependence of Heat Transfer Isotherml: Keep temperature const. Insulation + Free expansion (uncontrolled expansion of a gas into vacuum) Heat transfer depends on the initial & final states, also on the path. -

Thermodynamic Propertiesproperties

ThermodynamicThermodynamic PropertiesProperties PropertyProperty TableTable -- from direct measurement EquationEquation ofof StateState -- any equation that relates P,v, and T of a substance jump ExerciseExercise 33--1212 A bucket containing 2 liters of R-12 is left outside in the atmosphere (0.1 MPa) a) What is the R-12 temperature assuming it is in the saturated state. b) the surrounding transfer heat at the rate of 1KW to the liquid. How long will take for all R-12 vaporize? See R-12 (diclorindifluormethane) on Table A-2 SolutionSolution -- pagepage 11 Part a) From table A-2, at the saturation pressure of 0.1 MPa one finds: • Tsaturation = - 30oC 3 • vliq = 0.000672 m /kg 3 • vvap = 0.159375 m /kg • hlv = 165KJ/kg (vaporization heat) SolutionSolution -- pagepage 22 Part b) The mass of R-12 is m = Volume/vL, m = 0.002/0.000672 = 2.98 kg The vaporization energy: Evap = vap energy * mass = 165*2.98 = 492 KJ Time = Heat/Power = 492 sec or 8.2 min GASGAS PROPERTIESPROPERTIES Ideal -Gas Equation of State M PV = nR T; n = u mol Universal gas constant is given on Ru = 8.31434 kJ/kmol-K = 8.31434 kPa-m3/kmol-k = 0.0831434 bar-m3/kmol-K = 82.05 L-atm/kmol-K = 1.9858 Btu/lbmol-R = 1545.35 ft-lbf/lbmol-R = 10.73 psia-ft3/lbmol-R EExamplexample Determine the particular gas constant for air (28.97 kg/kmol) and hydrogen (2.016 kg/kmol). kJ 8.1417 kJ = Ru = kmol − K = 0.287 Rair kg M 28.97 kg − K kmol kJ 8.1417 kJ = kmol − K = 4.124 Rhydrogen kg 2.016 kg − K kmol IdealIdeal GasGas “Law”“Law” isis aa simplesimple EquationEquation ofof StateState PV = MRT Pv = RT PV = NRuT P V P V 1 1 = 2 2 T1 T2 QuestionQuestion …...…..