2: Chinese Ethnic Identity in Suriname

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand. -

Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Min Zhou Editor Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Editor Min Zhou University of California Los Angeles, CA USA

Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Min Zhou Editor Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Editor Min Zhou University of California Los Angeles, CA USA ISBN 978-981-10-5594-2 ISBN 978-981-10-5595-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5595-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950830 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Cover image © KTSDESIGN / Getty Images Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America

Department of Justice Weapons and money seized by U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America BY R. EVAN ELLis n June 2010, the sacking of Secretary of Justice Romeu Tuma Júnior for allegedly being an agent of the Chinese mafia rocked Brazilian politics.1 Three years earlier, in July 2007, the Ihead of the Colombian national police, General Oscar Naranjo, made the striking procla- mation that “the arrival of the Chinese and Russian mafias in Mexico and all of the countries in the Americas is more than just speculation.”2 Although, to date, the expansion of criminal ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Latin America has lagged behind the exponen- tial growth of trade and investment between the two regions, the incidents mentioned above high- light that criminal ties between the regions are becoming an increasingly problematic by-product of expanding China–Latin America interactions, with troubling implications for both regions. Although data to quantify the character and extent of such ties are lacking, public evidence suggests that criminal activity spanning the two regions is principally concentrated in four cur- rent domains and two potentially emerging areas. The four groupings of current criminal activ- ity between China and Latin America are extortion of Chinese communities in Latin America by groups with ties to China, trafficking in persons from China through Latin America into the United States or Canada, trafficking in narcotics and precursor chemicals, and trafficking in con- traband goods. The two emerging areas are arms trafficking and money laundering. It is important to note that this analysis neither implicates the Chinese government in such ties nor absolves it, although a consideration of incentives suggests that it is highly unlikely that the government would be involved in any systematic fashion. -

9: the 2005 Legislative Elections

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:23 Sep 2021 9. THE 2005 LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS The 2003 Commemoration of Chinese Immigration Day heralded the suc- cessful creation of Chinese ethnicity as a political project, the goal of which was participation in the next round of apanjaht political power- sharing in 2005. -

Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1 UvA Dissertation SieFat Tjon B. Paul Chinese New Migrants in Suriname Faculty of Social and Behavioural The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing Sciences The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing ofEthnic The Inevitability Paul B. -

ICAS 10 Programme Book

ICAS 10 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 20-23 JULY 2017 THE 10TH INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION OF ASIA SCHOLARS CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 20–23 JULY 2017 CHIANG MAI THAILAND ICAS 10 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 20-23 JULY 2017 CONTENTS 2-3 Welcome 4-5 Venue Floor Plan 6-7 Schedule at a Glance 8-11 Special Events 12-21 Film Screenings 22-27 Exhibitions THE 10TH 28-107 Panel Schedule INTERNATIONAL 108-127 CONVENTION OF Advertisements ASIA SCHOLARS 128-136 List of Participants CONFERENCE 137-144 List of Participant PROGRAMME Affiliated Institutions Notes 20–23 JULY 2017 CHIANG MAI THAILAND CO-SPONSORS Chiang Mai City Arts & Cultural Center Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Thailand Convention & Exhibition Bureau ICAS 10 WELCOME 20-23 JULY 2017 WELCOME TO ALL ICAS 10 PARTICIPANTS On behalf the Local Organising Committee, I would like to extend our warm welcome to all participants of ICAS10, taking place from 20-23July 2017 in Chiang Mai. As the 10th edition of ICAS is taking place in Asia, it will be greatly beneficial and intellectually challenging to invite Asia scholars to use this platform to discuss and exchange ideas on how we can better understand the changes that are happening in this region today. The conference is envisaged as an opportunity for participants to question the old paradigms and to search for new ones that can help us to analytically investigate the emerging economic, political and social order, as well as to conceive a realisation of the need for a new methodology to help us in better dealing with the problems of environment degradation, migration, authoritarianism, ethnic conflict, inequality, commoditisation of culture, and so forth. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Chinese Migration in Africa

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO 24 China in Africa Project January 2009 Chinese Migration in Africa Yoon Jung Park s ir a ff A l a n o ti a n er nt f I o te titu Ins s. an ht Afric ig South ins bal . Glo African perspectives ABOUT SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think-tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s occasional papers present topical, incisive analyses, offering a variety of perspectives on key policy issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policy- making; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. This paper is the outcome of research commissioned by SAIIA’s China in Africa Project. ABOUT THE CHINA IN AFRICA PROJECT SAIIA’s ‘China in Africa’ research project investigates the emerging relationship between China and Africa; analyses China’s trade and foreign policy towards the continent; and studies the implications of this strategic co-operation in the political, military, economic and diplomatic fields. -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

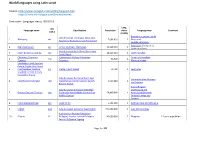

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

The Social Support of Elderly Chinese Migrants in New Zealand

Enhancing Quality of Life: The Social Support of Elderly Chinese Migrants in New Zealand Jingjing Zhang A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology The University of Auckland 2014 Abstract This thesis explores the quality of life of elderly Chinese migrants living in New Zealand. Specifically, by taking into consideration types and sources of support, it investigates the relationship between social support and quality of life. The analysis is contextualized within a transnational environment to elucidate how the multi-dimensional social support from family, community/government and transnational social networks contributes to elderly migrants’ perception of quality of life. In this study, both quality of life and social support are viewed as subjective concepts, based on individual perceptions and experiences. Theoretically, the thesis uses a social exchange perspective and the findings are derived primarily from 35 semi-structured in-depth interviews with elderly Chinese migrants who were aged 60 years or over and had lived in New Zealand for three years or more. Secondary data from statistics, government policies and previous research are also employed for the purposes of discussion and comparison. The findings indicate that the quality of life of elderly Chinese migrants in New Zealand is shaped by the interaction of various types and sources of social support. Providing financial, practical, informational and emotional support, family support is perceived as essential to participants’ quality of life in the early stages of iii migration. However, while family remains the major source of emotional support, government and ethnic communities, because they engender a sense of independence from family, become over time more important in regard to financial, practical, informational support. -

The 'Old Chinese'

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 7 THE ‘OLD CHINESE’ ROUTE TO PARTICIPATION: POLITICS OF CHINESENESS The anti-Chinese sentiments following in the wake of New Chinese immigration were increasing precisely in a period when ethnic Chinese had the best chance to acquire a share of political power in Suriname.