The 'Old Chinese'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif 1 Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif

Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif 1 Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif Voici la liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux, permettant d'utiliser les services téléphoniques dans un autre pays. La liste correspond à celle établie par l'Union internationale des télécommunications, dans sa recommandation UIT-T E.164. du 1er février 2004. Liste par pays | Liste par indicatifs Le symbole « + » devant les indicatifs symbolise la séquence d’accès vers l’international. Cette séquence change suivant le pays d’appel ou le terminal utilisé. Depuis la majorité des pays (dont la France), « + » doit être remplacé par « 00 » (qui est le préfixe recommandé). Par exemple, pour appeler en Hongrie (dont l’indicatif international est +36) depuis la France, il faut composer un Indicatifs internationaux par zone numéro du type « 0036######### ». En revanche, depuis les États-Unis, le Canada ou un pays de la zone 1 (Amérique du Nord et Caraïbes), « + » doit être composé comme « 011 ». D’autres séquences sont utilisées en Russie et dans les anciens pays de l’URSS, typiquement le « 90 ». Autrefois, la France utilisait à cette fin le « 19 ». Sur certains téléphones mobiles, il est possible d’entrer le symbole « + » directement en maintenant la touche « 0 » pressée plus longtemps au début du numéro à composer. Mais à partir d’un poste fixe, le « + » n'est pas accessible et il faut généralement taper à la main la séquence d’accès (code d’accès vers l'international) selon le pays d’où on appelle. Zone 0 La zone 0 est pour l'instant réservée à une utilisation future non encore établie. -

An Argument from Design

Raising the Standard: An Argument from Design Tony Burton Abstract The creative process and principles informing the design of some special purpose and other flags lead to conclusions for flag design in general. The dynamics of metaphor and shape- shifting are considered. The scope for greater pageantry and innovation in flag design is explored. Current national flags of complex or awkward design present a challenge. Possible remedies are suggested. To paraphrase a famous utterance, the known delivers the unknown, and as at least one national flag of recent vintage demonstrates, the unknown can lead to an unforeseen, but serendipitous result. Among the many instances of how not to design a flag, how to is more worthwhile. Vexillologists have higher standards. Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 83 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN Tony Burton Flags Australia Tony Burton—Raising the Standard 84 Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology—2011 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN INTRODUCTION FLAG DESIGN REALITIES GUIDELINES SOME CONGRESS FLAGS ICV 24 ICV 26 SHAPE-SHIFTING ICV 8 OTHER FLAGS CANADA BANGLADESH SURINAM(E) SOUTH AFRICA DESIGN CHANGE POSSIBILITIES MOZAMBIQUE CYPRUS DOMINICA ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES DESIGN ECONOMY AND A FUTURE FLAG AUSTRALIA EUREKA A CONSERVATIVE APPROACH RADICAL ORIGAMI A PARAGON OF DESIGN PRACTICAL GUIDELINES THE EUREKA MOMENT —A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX A BANNER OF THE 26TH ICV SYDNEY 2015 APPENDIX B CANADA’S FLAG DESIGN QUEST Tony Burton—Raising the Standard 85 Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology—2011 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN INTRODUCTION Flags have evolved in many ways from the medieval models paraphrased in the title slide— and not always with their clarity and flair. -

Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America

Department of Justice Weapons and money seized by U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America BY R. EVAN ELLis n June 2010, the sacking of Secretary of Justice Romeu Tuma Júnior for allegedly being an agent of the Chinese mafia rocked Brazilian politics.1 Three years earlier, in July 2007, the Ihead of the Colombian national police, General Oscar Naranjo, made the striking procla- mation that “the arrival of the Chinese and Russian mafias in Mexico and all of the countries in the Americas is more than just speculation.”2 Although, to date, the expansion of criminal ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Latin America has lagged behind the exponen- tial growth of trade and investment between the two regions, the incidents mentioned above high- light that criminal ties between the regions are becoming an increasingly problematic by-product of expanding China–Latin America interactions, with troubling implications for both regions. Although data to quantify the character and extent of such ties are lacking, public evidence suggests that criminal activity spanning the two regions is principally concentrated in four cur- rent domains and two potentially emerging areas. The four groupings of current criminal activ- ity between China and Latin America are extortion of Chinese communities in Latin America by groups with ties to China, trafficking in persons from China through Latin America into the United States or Canada, trafficking in narcotics and precursor chemicals, and trafficking in con- traband goods. The two emerging areas are arms trafficking and money laundering. It is important to note that this analysis neither implicates the Chinese government in such ties nor absolves it, although a consideration of incentives suggests that it is highly unlikely that the government would be involved in any systematic fashion. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

9: the 2005 Legislative Elections

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:23 Sep 2021 9. THE 2005 LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS The 2003 Commemoration of Chinese Immigration Day heralded the suc- cessful creation of Chinese ethnicity as a political project, the goal of which was participation in the next round of apanjaht political power- sharing in 2005. -

Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1 UvA Dissertation SieFat Tjon B. Paul Chinese New Migrants in Suriname Faculty of Social and Behavioural The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing Sciences The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing ofEthnic The Inevitability Paul B. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

Kwakoe, Baba & Mai: Revisiting Dutch Colo- Nialism in Suriname

Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. IV, Issue 2 Kwakoe, Baba & Mai: Revisiting Dutch Colo- nialism in Suriname Praveen Sewgobind The former Dutch colony of Suriname is, interestingly, geographically located in what is called “Latin Ameri- ca,” yet is culturally and politically more entangled with the Caribbean region. Historically, these links have their roots in a colonial history and contemporaneity that aligns European powers such as Britain and the Neth- erlands. The historical fact that the English colony of Suriname was exchanged with New Amsterdam (which later became New York) in 1667, is indicative for the way large swathes of land that were inhabited by non- white indigenous and enslaved peoples became subject 264 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. IV, Issue 2 of colonial trade-offs. For Suriname, three hundred and twenty years of European colonialism have resulted in the presence of large African and South Asian commu- nities in the Caribbean country. Having gained formal independence relatively recently (in 1975), British and Dutch colonial politics have shaped many aspects of socio-political and cultural life. This paper investigates the ways in which African and South Asian communities have become part of a racialized schema imposed by a system of white supremacy under colonialism. To make my argument, I perform a case study through which I analyze two statues in the capital city of Par- amaribo. Firstly, I will problematize Kwakoe, a statue in the heart of the centre of the city, representing the abolition of slavery, which de facto occurred in 1873. Secondly, I come to terms with a statue named Baba and Mai, which represents the arrival of South Asian contracted labourers after 1873. -

2: Chinese Ethnic Identity in Suriname

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 2 CHINESE ETHNIC IDENTITY IN SURINAME No one in Suriname will dispute the existence of a Chinese ethnic group in Suriname, but defining Chinese identity and ethnicity in Suriname is by no means simple. Despite the persistent presence of people everyone agrees to label ‘Chinese’, there are no studies to explain why a clear-cut ethnic Chinese segment should persist in the Caribbean. -

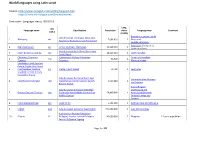

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

The Strategic Dimension of Chinese Engagement with Latin America

ISSN 2330-9296 Perry Paper Series, no. 1 The Strategic Dimension of Chinese Engagement with Latin America R. Evan Ellis William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies 2013 The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of Dr. William J. Perry, the Perry Center, or the US Depart- ment of Defense. Book Design: Patricia Kehoe Cover Design: Vitmary (Vivian) Rodriguez CONTENTS FOREWORD V PREFACE VII CHAPTER ONE Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO The Impact of China on the Region 11 CHAPTER THREE The Question of Chinese Soft Power 33 CHAPTER FOUR Chinese Commercial Activities in Strategic Sectors 51 CHAPTER FIVE The PRC–Latin America Military Relationship 85 CHAPTER SIX China–Latin America Organized Crime Ties 117 CHAPTER SEVEN A “Strategic Triangle” between the PRC, the US, and Latin America? 135 CHAPTER EIGHT The Way Forward 153 FOREWORD With the publication of this volume, the William J. Perry Center for Hemi- spheric Defense Studies presents the first of the Perry Papers, a series of stim- ulating thought pieces on timely security and defense topics of global propor- tions from a regional perspective. The Perry Papers honor the 19th Secretary of Defense, Dr. William J. Perry, whose vision serves as the foundation for the first three of the five current regional security studies centers. Dr. Perry has espoused the belief that education “provides the basis for partner nations’ establishing and building enhanced relations based on mutual re- spect and understanding, leading to confidence, collaboration, and cooperation.” The faculty and staff of the Perry Center believe strongly in the same princi- ples.