9: the 2005 Legislative Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants Liste Des Participants

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS 142nd IPU Assembly and Related Meetings (virtual) 24 to 27 May 2021 - 2 - Mr./M. Duarte Pacheco President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Président de l'Union interparlementaire Mr./M. Martin Chungong Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Secrétaire général de l'Union interparlementaire - 3 - I. MEMBERS - MEMBRES AFGHANISTAN RAHMANI, Mir Rahman (Mr.) Speaker of the House of the People Leader of the delegation EZEDYAR, Mohammad Alam (Mr.) Deputy Speaker of the House of Elders KAROKHAIL, Shinkai (Ms.) Member of the House of the People ATTIQ, Ramin (Mr.) Member of the House of the People REZAIE, Shahgul (Ms.) Member of the House of the People ISHCHY, Baktash (Mr.) Member of the House of the People BALOOCH, Mohammad Nadir (Mr.) Member of the House of Elders HASHIMI, S. Safiullah (Mr.) Member of the House of Elders ARYUBI, Abdul Qader (Mr.) Secretary General, House of the People Member of the ASGP NASARY, Abdul Muqtader (Mr.) Secretary General, House of Elders Member of the ASGP HASSAS, Pamir (Mr.) Acting Director of Relations to IPU Secretary to the delegation ALGERIA - ALGERIE GOUDJIL, Salah (M.) Président du Conseil de la Nation Président du Groupe, Chef de la délégation BOUZEKRI, Hamid (M.) Vice-Président du Conseil de la Nation (RND) BENBADIS, Fawzia (Mme) Membre du Conseil de la Nation Comité sur les questions relatives au Moyen-Orient KHARCHI, Ahmed (M.) Membre du Conseil de la Nation (FLN) DADA, Mohamed Drissi (M.) Secrétaire Général, Conseil de la Nation Secrétaire général -

Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America

Department of Justice Weapons and money seized by U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America BY R. EVAN ELLis n June 2010, the sacking of Secretary of Justice Romeu Tuma Júnior for allegedly being an agent of the Chinese mafia rocked Brazilian politics.1 Three years earlier, in July 2007, the Ihead of the Colombian national police, General Oscar Naranjo, made the striking procla- mation that “the arrival of the Chinese and Russian mafias in Mexico and all of the countries in the Americas is more than just speculation.”2 Although, to date, the expansion of criminal ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Latin America has lagged behind the exponen- tial growth of trade and investment between the two regions, the incidents mentioned above high- light that criminal ties between the regions are becoming an increasingly problematic by-product of expanding China–Latin America interactions, with troubling implications for both regions. Although data to quantify the character and extent of such ties are lacking, public evidence suggests that criminal activity spanning the two regions is principally concentrated in four cur- rent domains and two potentially emerging areas. The four groupings of current criminal activ- ity between China and Latin America are extortion of Chinese communities in Latin America by groups with ties to China, trafficking in persons from China through Latin America into the United States or Canada, trafficking in narcotics and precursor chemicals, and trafficking in con- traband goods. The two emerging areas are arms trafficking and money laundering. It is important to note that this analysis neither implicates the Chinese government in such ties nor absolves it, although a consideration of incentives suggests that it is highly unlikely that the government would be involved in any systematic fashion. -

Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Tjon Sie Fat:AUP/Buijn 14-08-2009 00:50 Pagina 1 UvA Dissertation SieFat Tjon B. Paul Chinese New Migrants in Suriname Faculty of Social and Behavioural The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing Sciences The Inevitability of Ethnic Performing ofEthnic The Inevitability Paul B. -

Download It From

IMD Partner in Democracy A NNUAL R EPORT 2005 The IMD – an institute of political parties for political parties The Institute for Multiparty Democracy (IMD) is an institute of political parties for political parties. Its mandate is to encourage the process of democratisation in young democracies by providing support to political parties as the core pillars of multi- party democracy. IMD works in a strictly non-partisan and inclusive manner. Through this approach, the Institute endeavours to contribute to properly functioning, sustainable pluralistic political party systems. It also supports the activities of civil society groups which play a healthy role in multi-party democracies, even though they are not part of any formal party structure. IMD was set up by seven Dutch political parties in 2000 in response to requests for support from around the world. The IMD’s founding members are the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), Liberal Party (VVD), Christian Democratic Party (CDA), Democratic Party (D66), Green Party (GroenLinks), Christian Union (ChristenUnie) and Reformed Party (SGP). Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy Korte Vijverberg 2 2513 AB The Hague The Netherlands Address per September 1, 2006: Passage 31 2511 AB The Hague The Netherlands T: +31 (0)70 311 5464 F: +31 (0)70 311 5465 E: [email protected] www.nimd.org IMD Partner in Democracy A NNUAL R EPORT 2005 Partners in Democracy Preface Without properly functioning political parties, resulted in a study for the European Parliament entitled democracies do not work well – a fact that is not yet No lasting Peace and Prosperity without Democracy & fully recognised within the international development Human Rights. -

Chapter Ii History of the Javanese in Suriname and Its

CHAPTER II HISTORY OF THE JAVANESE IN SURINAME AND ITS ORGANIZATIONS In this chapter the author explicate about the history of the first Javanese arriving in Suriname. The history of how Javanese people can live in Suriname. It also explicate the history of the Javanese organization confirmed in Suriname. The encouragement estbalishing Javansese organizations as aim to change the pereption of the Surinamese population towards the Javanese diaspora. furthermore, this chapter also discusses about the activities of the Javanese organization in Suriname. 2.1 The History of Javanese in Suriname Suriname is a country located in the north coast of South America which is estimated 163.821 km2. According to the General Bureau of Statistic (ABS), Suriname posses a population of about 568.30128with Paramaribo as the capital. The Capital Lies 15 KM from the Atlantic Ocean connected with the Suriname River. It borders with Guyana in the East, French Guyana in the West, Brazil in the South and the Atlantic Ocean in the North. Suriname was formerly known as Dutch Guyana and was a plantation colony of the Netherlands. Dutch colonized started in 1667 and gained ultimately its independence on November 25, 1975.29 The native 28 World Population, Suriname Population 2018 , accessed in http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/suriname-population/ (15/02/2018 21:43 WIB) 29 Vernom Domingo, Surinamese Migration and Development , British Water Review, vol. 14, Issue 1, June 1995. p.8 29 people of Suriname are Arowak and Caraib, which are also the native people of South America. Suriname has a tropical climate with four seasons e.g minor rainy season, minor dry season, major rainy season and major dry season. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

2: Chinese Ethnic Identity in Suriname

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 2 CHINESE ETHNIC IDENTITY IN SURINAME No one in Suriname will dispute the existence of a Chinese ethnic group in Suriname, but defining Chinese identity and ethnicity in Suriname is by no means simple. Despite the persistent presence of people everyone agrees to label ‘Chinese’, there are no studies to explain why a clear-cut ethnic Chinese segment should persist in the Caribbean. -

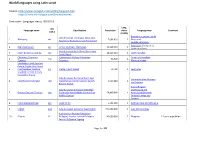

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Report of the Oas Electoral Observation Mission for the General Elections in the Republic of Suriname on May 25, 2010

PERMANENT COUNCIL OEA/Ser.G CP/doc.4532/11 4 February 2011 VERBATIM FINAL REPORT OF THE OAS ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FOR THE GENERAL ELECTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF SURINAME ON MAY 25, 2010 http://scm.oas.org/pdfs/2011/CP25611.pdf ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES FINAL REPORT OF THE OAS ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FOR THE GENERAL ELECTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF SURINAME ON MAY 25, 2010 Secretariat for Political Affairs CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. ....1 CHAPTER I. BACKGROUND AND NATURE OF THE MISSION............................................3 CHAPTER II. POLITICAL SYSTEM AND ELECTORAL ORGANIZATION ..........................4 A. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW........................................................................... 4 B. POLITICAL SYSTEM AND ACTORS......................................................... 5 C. THE ELECTORAL SYSTEM........................................................................ 8 D. VOTING PROCEDURE................................................................................. 8 E. POLITICAL FINANCING........................................................................... 10 CHAPTER III. MISSION ACTIVITIES AND OBSERVATIONS.....................................11 A. PRE-ELECTION.............................................................................................11 B. ELECTION DAY............................................................................................11 C. POST-ELECTION -

Mangroves, Mudbanks and Seawalls: Political Ecology of Adaptation to Sea Level Rise in Suriname Ravic Nijbroek University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Mangroves, Mudbanks and Seawalls: Political Ecology of Adaptation to Sea Level Rise in Suriname Ravic Nijbroek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Climate Commons, and the Geography Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nijbroek, Ravic, "Mangroves, Mudbanks and Seawalls: Political Ecology of Adaptation to Sea Level Rise in Suriname" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4184 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mangroves, Mudbanks and Seawalls: Political Ecology of Adaptation to Sea Level Rise in Suriname by Ravic P. Nijbroek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography and Environment Science and Policy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Pratyusha Basu, Ph.D. Kevin Archer, Ph.D. Martin Bosman, Ph.D. Rebecca Johns, Ph.D. Michael Miller, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 27, 2012 Keywords: Discourse, Power, Knowledge, Coastal Management, Climate Change Copyright © 2012, Ravic P. Nijbroek DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my mother Linda Jacqueline Asin, who instilled in me the values of hard work, humility, and speaking for the voiceless. She passed away too soon and was not able to join me in celebrating this accomplishment. -

The 'Old Chinese'

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing Tjon Sie Fat, P.B. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tjon Sie Fat, P. B. (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Vossiuspers - Amsterdam University Press. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056295981-chinese-new-migrants-in-suriname.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 7 THE ‘OLD CHINESE’ ROUTE TO PARTICIPATION: POLITICS OF CHINESENESS The anti-Chinese sentiments following in the wake of New Chinese immigration were increasing precisely in a period when ethnic Chinese had the best chance to acquire a share of political power in Suriname.