William P. Thurston the Geometry and Topology of Three-Manifolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

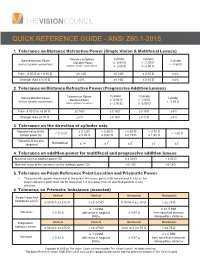

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Calculus & Analytic Geometry

TQS 126 Spring 2008 Quinn Calculus & Analytic Geometry III Quadratic Equations in 3-D Match each function to its graph 1. 9x2 + 36y2 +4z2 = 36 2. 4x2 +9y2 4z2 =0 − 3. 36x2 +9y2 4z2 = 36 − 4. 4x2 9y2 4z2 = 36 − − 5. 9x2 +4y2 6z =0 − 6. 9x2 4y2 6z =0 − − 7. 4x2 + y2 +4z2 4y 4z +36=0 − − 8. 4x2 + y2 +4z2 4y 4z 36=0 − − − cone • ellipsoid • elliptic paraboloid • hyperbolic paraboloid • hyperboloid of one sheet • hyperboloid of two sheets 24 TQS 126 Spring 2008 Quinn Calculus & Analytic Geometry III Parametric Equations (§10.1) and Vector Functions (§13.1) Definition. If x and y are given as continuous function x = f(t) y = g(t) over an interval of t-values, then the set of points (x, y)=(f(t),g(t)) defined by these equation is a parametric curve (sometimes called aplane curve). The equations are parametric equations for the curve. Often we think of parametric curves as describing the movement of a particle in a plane over time. Examples. x = 2cos t x = et 0 t π 1 t e y = 3sin t ≤ ≤ y = ln t ≤ ≤ Can we find parameterizations of known curves? the line segment circle x2 + y2 =1 from (1, 3) to (5, 1) Why restrict ourselves to only moving through planes? Why not space? And why not use our nifty vector notation? 25 Definition. If x, y, and z are given as continuous functions x = f(t) y = g(t) z = h(t) over an interval of t-values, then the set of points (x,y,z)= (f(t),g(t), h(t)) defined by these equation is a parametric curve (sometimes called a space curve). -

Imaginary Crystals Made Real

Imaginary crystals made real Simone Taioli,1, 2 Ruggero Gabbrielli,1 Stefano Simonucci,3 Nicola Maria Pugno,4, 5, 6 and Alfredo Iorio1 1Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic 2European Centre for Theoretical Studies in Nuclear Physics and Related Areas (ECT*), Bruno Kessler Foundation & Trento Institute for Fundamental Physics and Applications (TIFPA-INFN), Trento, Italy 3Department of Physics, University of Camerino, Italy & Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Perugia, Italy 4Laboratory of Bio-inspired & Graphene Nanomechanics, Department of Civil, Environmental and Mechanical Engineering, University of Trento, Italy 5School of Engineering and Materials Science, Queen Mary University of London, UK 6Center for Materials and Microsystems, Bruno Kessler Foundation, Trento, Italy (Dated: August 20, 2018) We realize Lobachevsky geometry in a simulation lab, by producing a carbon-based mechanically stable molecular structure, arranged in the shape of a Beltrami pseudosphere. We find that this structure: i) corresponds to a non-Euclidean crystallographic group, namely a loxodromic subgroup of SL(2; Z); ii) has an unavoidable singular boundary, that we fully take into account. Our approach, substantiated by extensive numerical simulations of Beltrami pseudospheres of different size, might be applied to other surfaces of constant negative Gaussian curvature, and points to a general pro- cedure to generate them. Our results also pave the way to test certain scenarios of the physics of curved spacetimes. Lobachevsky used to call his Non-Euclidean geometry \imaginary geometry" [1]. Beltrami showed that this geom- etry can be realized in our Euclidean 3-space, through surfaces of constant negative Gaussian curvature K [2]. -

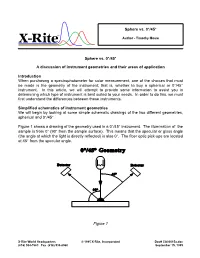

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

Recognizing Surfaces

RECOGNIZING SURFACES Ivo Nikolov and Alexandru I. Suciu Mathematics Department College of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Abstract The subject of this poster is the interplay between the topology and the combinatorics of surfaces. The main problem of Topology is to classify spaces up to continuous deformations, known as homeomorphisms. Under certain conditions, topological invariants that capture qualitative and quantitative properties of spaces lead to the enumeration of homeomorphism types. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. The poster focuses on the main topological invariants of two-dimensional manifolds—orientability, number of boundary components, genus, and Euler characteristic—and how these invariants solve the classification problem for compact surfaces. The poster introduces a Java applet that was written in Fall, 1998 as a class project for a Topology I course. It implements an algorithm that determines the homeomorphism type of a closed surface from a combinatorial description as a polygon with edges identified in pairs. The input for the applet is a string of integers, encoding the edge identifications. The output of the applet consists of three topological invariants that completely classify the resulting surface. Topology of Surfaces Topology is the abstraction of certain geometrical ideas, such as continuity and closeness. Roughly speaking, topol- ogy is the exploration of manifolds, and of the properties that remain invariant under continuous, invertible transforma- tions, known as homeomorphisms. The basic problem is to classify manifolds according to homeomorphism type. In higher dimensions, this is an impossible task, but, in low di- mensions, it can be done. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. -

Structural Forms 1

Key principles The hyperboloid of revolution is a Surface and may be generated by revolving a Hyperbola about its conjugate axis. The outline of the elevation will be a Hyperbola. When the conjugate axis is vertical all horizontal sections are circles. The horizontal section at the mid point of the conjugate axis is known as the Throat. The diagram shows the incomplete construction for drawing a hyperbola in a rectangle. (a) Draw the outline of the both branches of the double hyperbola in the rectangle. The diagram shows the incomplete Elevation of a hyperboloid of revolution. (a) Determine the position of the throat circle in elevation. (b) Draw the outline of the both branches of the double hyperbola in elevation. DESIGN & COMMUNICATION GRAPHICS Structural forms 1 NAME: ______________________________ DATE: _____________ The diagram shows the plan and incomplete elevation of an object based on the hyperboloid of revolution. The focal points and transverse axis of the hyperbola are also shown. (a) Using the given information draw the outline of the elevation.. F The diagram shows the axis, focal points and transverse axis of a double hyperbola. (a) Draw the outline of both branches of the double hyperbola. (b) The difference between the focal distances for any point on a double hyperbola is constant and equal to the length of the transverse axis. (c) Indicate this principle on the drawing below. DESIGN & COMMUNICATION GRAPHICS Structural forms 2 NAME: ______________________________ DATE: _____________ Key principles The diagram shows the plan and incomplete elevation of a hyperboloid of revolution. The hyperboloid of revolution may also be generated by revolving one skew line about another. -

The Real Projective Spaces in Homotopy Type Theory

The real projective spaces in homotopy type theory Ulrik Buchholtz Egbert Rijke Technische Universität Darmstadt Carnegie Mellon University Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract—Homotopy type theory is a version of Martin- topology and homotopy theory developed in homotopy Löf type theory taking advantage of its homotopical models. type theory (homotopy groups, including the fundamen- In particular, we can use and construct objects of homotopy tal group of the circle, the Hopf fibration, the Freuden- theory and reason about them using higher inductive types. In this article, we construct the real projective spaces, key thal suspension theorem and the van Kampen theorem, players in homotopy theory, as certain higher inductive types for example). Here we give an elementary construction in homotopy type theory. The classical definition of RPn, in homotopy type theory of the real projective spaces as the quotient space identifying antipodal points of the RPn and we develop some of their basic properties. n-sphere, does not translate directly to homotopy type theory. R n In classical homotopy theory the real projective space Instead, we define P by induction on n simultaneously n with its tautological bundle of 2-element sets. As the base RP is either defined as the space of lines through the + case, we take RP−1 to be the empty type. In the inductive origin in Rn 1 or as the quotient by the antipodal action step, we take RPn+1 to be the mapping cone of the projection of the 2-element group on the sphere Sn [4]. -

Lattice Points on Hyperboloids of One Sheet

New York Journal of Mathematics New York J. Math. 20 (2014) 1253{1268. Lattice points on hyperboloids of one sheet Arthur Baragar Abstract. The problem of counting lattice points on a hyperboloid of two sheets is Gauss' circle problem in hyperbolic geometry. The problem of counting lattice points on a hyperboloid of one sheet does not have the same geometric interpretation, and in general, the solution(s) to Gauss' circle problem gives a lower bound, but not an upper bound. In this paper, we describe an exception. Given an ample height, and a lattice on a hyperboloid of one sheet generated by a point in the interior of the effective cone, the problem can be reduced to Gauss' circle problem. Contents Introduction 1253 1. The Gauss circle problem 1255 1.1. Euclidean case 1255 1.2. Hyperbolic case 1255 2. An instructive example 1256 3. The main result 1260 4. Motivation 1264 Appendix: The pseudosphere in Lorentz space 1265 References 1267 Introduction Let J be an (m + 1) × (m + 1) real symmetric matrix with m ≥ 2 and signature (m; 1) (that is, J has m positive eigenvalues and one negative t m+1 eigenvalue). Then x ◦ y := x Jy is a Lorentz product and R equipped m;1 with this product is a Lorentz space, denoted R . The hypersurface m;1 Vk = fx 2 R : x ◦ x = kg Received February 26, 2013; revised December 9, 2014. 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. 11D45, 11P21, 20H10, 22E40, 11N45, 14J28, 11G50, 11H06. Key words and phrases. Gauss' circle problem, lattice points, orbits, Hausdorff dimen- sion, ample cone.