CIRCLE and SPHERE GEOMETRY. [July

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

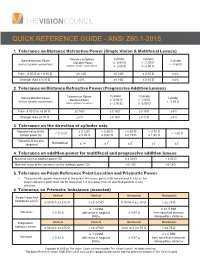

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Special Isocubics in the Triangle Plane

Special Isocubics in the Triangle Plane Jean-Pierre Ehrmann and Bernard Gibert June 19, 2015 Special Isocubics in the Triangle Plane This paper is organized into five main parts : a reminder of poles and polars with respect to a cubic. • a study on central, oblique, axial isocubics i.e. invariant under a central, oblique, • axial (orthogonal) symmetry followed by a generalization with harmonic homolo- gies. a study on circular isocubics i.e. cubics passing through the circular points at • infinity. a study on equilateral isocubics i.e. cubics denoted 60 with three real distinct • K asymptotes making 60◦ angles with one another. a study on conico-pivotal isocubics i.e. such that the line through two isoconjugate • points envelopes a conic. A number of practical constructions is provided and many examples of “unusual” cubics appear. Most of these cubics (and many other) can be seen on the web-site : http://bernard.gibert.pagesperso-orange.fr where they are detailed and referenced under a catalogue number of the form Knnn. We sincerely thank Edward Brisse, Fred Lang, Wilson Stothers and Paul Yiu for their friendly support and help. Chapter 1 Preliminaries and definitions 1.1 Notations We will denote by the cubic curve with barycentric equation • K F (x,y,z) = 0 where F is a third degree homogeneous polynomial in x,y,z. Its partial derivatives ∂F ∂2F will be noted F ′ for and F ′′ for when no confusion is possible. x ∂x xy ∂x∂y Any cubic with three real distinct asymptotes making 60◦ angles with one another • will be called an equilateral cubic or a 60. -

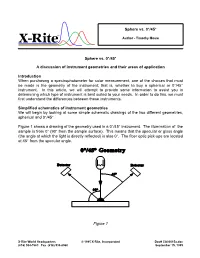

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

Delaunay Triangulations of Points on Circles Arxiv:1803.11436V1 [Cs.CG

Delaunay Triangulations of Points on Circles∗ Vincent Despr´e † Olivier Devillers† Hugo Parlier‡ Jean-Marc Schlenker‡ April 2, 2018 Abstract Delaunay triangulations of a point set in the Euclidean plane are ubiq- uitous in a number of computational sciences, including computational geometry. Delaunay triangulations are not well defined as soon as 4 or more points are concyclic but since it is not a generic situation, this difficulty is usually handled by using a (symbolic or explicit) perturbation. As an alter- native, we propose to define a canonical triangulation for a set of concyclic points by using a max-min angle characterization of Delaunay triangulations. This point of view leads to a well defined and unique triangulation as long as there are no symmetric quadruples of points. This unique triangulation can be computed in quasi-linear time by a very simple algorithm. 1 Introduction Let P be a set of points in the Euclidean plane. If we assume that P is in general position and in particular do not contain 4 concyclic points, then the Delaunay triangulation DT (P ) is the unique triangulation over P such that the (open) circumdisk of each triangle is empty. DT (P ) has a number of interesting properties. The one that we focus on is called the max-min angle property. For a given triangulation τ, let A(τ) be the list of all the angles of τ sorted from smallest to largest. DT (P ) is the triangulation which maximizes A(τ) for the lexicographical order [4,7] . In dimension 2 and for points in general position, this max-min angle arXiv:1803.11436v1 [cs.CG] 30 Mar 2018 property characterizes Delaunay triangulations and highlights one of their most ∗This work was supported by the ANR/FNR project SoS, INTER/ANR/16/11554412/SoS, ANR-17-CE40-0033. -

Angles in a Circle and Cyclic Quadrilateral MODULE - 3 Geometry

Angles in a Circle and Cyclic Quadrilateral MODULE - 3 Geometry 16 Notes ANGLES IN A CIRCLE AND CYCLIC QUADRILATERAL You must have measured the angles between two straight lines. Let us now study the angles made by arcs and chords in a circle and a cyclic quadrilateral. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to • verify that the angle subtended by an arc at the centre is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle; • prove that angles in the same segment of a circle are equal; • cite examples of concyclic points; • define cyclic quadrilterals; • prove that sum of the opposite angles of a cyclic quadrilateral is 180o; • use properties of cyclic qudrilateral; • solve problems based on Theorems (proved) and solve other numerical problems based on verified properties; • use results of other theorems in solving problems. EXPECTED BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE • Angles of a triangle • Arc, chord and circumference of a circle • Quadrilateral and its types Mathematics Secondary Course 395 MODULE - 3 Angles in a Circle and Cyclic Quadrilateral Geometry 16.1 ANGLES IN A CIRCLE Central Angle. The angle made at the centre of a circle by the radii at the end points of an arc (or Notes a chord) is called the central angle or angle subtended by an arc (or chord) at the centre. In Fig. 16.1, ∠POQ is the central angle made by arc PRQ. Fig. 16.1 The length of an arc is closely associated with the central angle subtended by the arc. Let us define the “degree measure” of an arc in terms of the central angle. -

Recognizing Surfaces

RECOGNIZING SURFACES Ivo Nikolov and Alexandru I. Suciu Mathematics Department College of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Abstract The subject of this poster is the interplay between the topology and the combinatorics of surfaces. The main problem of Topology is to classify spaces up to continuous deformations, known as homeomorphisms. Under certain conditions, topological invariants that capture qualitative and quantitative properties of spaces lead to the enumeration of homeomorphism types. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. The poster focuses on the main topological invariants of two-dimensional manifolds—orientability, number of boundary components, genus, and Euler characteristic—and how these invariants solve the classification problem for compact surfaces. The poster introduces a Java applet that was written in Fall, 1998 as a class project for a Topology I course. It implements an algorithm that determines the homeomorphism type of a closed surface from a combinatorial description as a polygon with edges identified in pairs. The input for the applet is a string of integers, encoding the edge identifications. The output of the applet consists of three topological invariants that completely classify the resulting surface. Topology of Surfaces Topology is the abstraction of certain geometrical ideas, such as continuity and closeness. Roughly speaking, topol- ogy is the exploration of manifolds, and of the properties that remain invariant under continuous, invertible transforma- tions, known as homeomorphisms. The basic problem is to classify manifolds according to homeomorphism type. In higher dimensions, this is an impossible task, but, in low di- mensions, it can be done. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. -

The Real Projective Spaces in Homotopy Type Theory

The real projective spaces in homotopy type theory Ulrik Buchholtz Egbert Rijke Technische Universität Darmstadt Carnegie Mellon University Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract—Homotopy type theory is a version of Martin- topology and homotopy theory developed in homotopy Löf type theory taking advantage of its homotopical models. type theory (homotopy groups, including the fundamen- In particular, we can use and construct objects of homotopy tal group of the circle, the Hopf fibration, the Freuden- theory and reason about them using higher inductive types. In this article, we construct the real projective spaces, key thal suspension theorem and the van Kampen theorem, players in homotopy theory, as certain higher inductive types for example). Here we give an elementary construction in homotopy type theory. The classical definition of RPn, in homotopy type theory of the real projective spaces as the quotient space identifying antipodal points of the RPn and we develop some of their basic properties. n-sphere, does not translate directly to homotopy type theory. R n In classical homotopy theory the real projective space Instead, we define P by induction on n simultaneously n with its tautological bundle of 2-element sets. As the base RP is either defined as the space of lines through the + case, we take RP−1 to be the empty type. In the inductive origin in Rn 1 or as the quotient by the antipodal action step, we take RPn+1 to be the mapping cone of the projection of the 2-element group on the sphere Sn [4]. -

The Sphere Packing Problem in Dimension 8 Arxiv:1603.04246V2

The sphere packing problem in dimension 8 Maryna S. Viazovska April 5, 2017 8 In this paper we prove that no packing of unit balls in Euclidean space R has density greater than that of the E8-lattice packing. Keywords: Sphere packing, Modular forms, Fourier analysis AMS subject classification: 52C17, 11F03, 11F30 1 Introduction The sphere packing constant measures which portion of d-dimensional Euclidean space d can be covered by non-overlapping unit balls. More precisely, let R be the Euclidean d vector space equipped with distance k · k and Lebesgue measure Vol(·). For x 2 R and d r 2 R>0 we denote by Bd(x; r) the open ball in R with center x and radius r. Let d X ⊂ R be a discrete set of points such that kx − yk ≥ 2 for any distinct x; y 2 X. Then the union [ P = Bd(x; 1) x2X d is a sphere packing. If X is a lattice in R then we say that P is a lattice sphere packing. The finite density of a packing P is defined as Vol(P\ Bd(0; r)) ∆P (r) := ; r > 0: Vol(Bd(0; r)) We define the density of a packing P as the limit superior ∆P := lim sup ∆P (r): r!1 arXiv:1603.04246v2 [math.NT] 4 Apr 2017 The number be want to know is the supremum over all possible packing densities ∆d := sup ∆P ; d P⊂R sphere packing 1 called the sphere packing constant. For which dimensions do we know the exact value of ∆d? Trivially, in dimension 1 we have ∆1 = 1. -

Application of Nine Point Circle Theorem

Application of Nine Point Circle Theorem Submitted by S3 PLMGS(S) Students Bianca Diva Katrina Arifin Kezia Aprilia Sanjaya Paya Lebar Methodist Girls’ School (Secondary) A project presented to the Singapore Mathematical Project Festival 2019 Singapore Mathematic Project Festival 2019 Application of the Nine-Point Circle Abstract In mathematics geometry, a nine-point circle is a circle that can be constructed from any given triangle, which passes through nine significant concyclic points defined from the triangle. These nine points come from the midpoint of each side of the triangle, the foot of each altitude, and the midpoint of the line segment from each vertex of the triangle to the orthocentre, the point where the three altitudes intersect. In this project we carried out last year, we tried to construct nine-point circles from triangulated areas of an n-sided polygon (which we call the “Original Polygon) and create another polygon by connecting the centres of the nine-point circle (which we call the “Image Polygon”). From this, we were able to find the area ratio between the areas of the original polygon and the image polygon. Two equations were found after we collected area ratios from various n-sided regular and irregular polygons. Paya Lebar Methodist Girls’ School (Secondary) 1 Singapore Mathematic Project Festival 2019 Application of the Nine-Point Circle Acknowledgement The students involved in this project would like to thank the school for the opportunity to participate in this competition. They would like to express their gratitude to the project supervisor, Ms Kok Lai Fong for her guidance in the course of preparing this project.