Examples of Manifolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spheres in Infinite-Dimensional Normed Spaces Are Lipschitz Contractible

PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 88. Number 3, July 1983 SPHERES IN INFINITE-DIMENSIONAL NORMED SPACES ARE LIPSCHITZ CONTRACTIBLE Y. BENYAMINI1 AND Y. STERNFELD Abstract. Let X be an infinite-dimensional normed space. We prove the following: (i) The unit sphere {x G X: || x II = 1} is Lipschitz contractible. (ii) There is a Lipschitz retraction from the unit ball of JConto the unit sphere. (iii) There is a Lipschitz map T of the unit ball into itself without an approximate fixed point, i.e. inffjjc - Tx\\: \\x\\ « 1} > 0. Introduction. Let A be a normed space, and let Bx — {jc G X: \\x\\ < 1} and Sx = {jc G X: || jc || = 1} be its unit ball and unit sphere, respectively. Brouwer's fixed point theorem states that when X is finite dimensional, every continuous self-map of Bx admits a fixed point. Two equivalent formulations of this theorem are the following. 1. There is no continuous retraction from Bx onto Sx. 2. Sx is not contractible, i.e., the identity map on Sx is not homotopic to a constant map. It is well known that none of these three theorems hold in infinite-dimensional spaces (see e.g. [1]). The natural generalization to infinite-dimensional spaces, however, would seem to require the maps to be uniformly-continuous and not merely continuous. Indeed in the finite-dimensional case this condition is automatically satisfied. In this article we show that the above three theorems fail, in the infinite-dimen- sional case, even under the strongest uniform-continuity condition, namely, for maps satisfying a Lipschitz condition. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

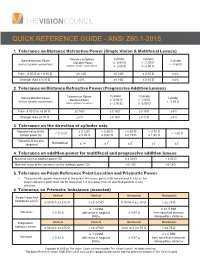

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

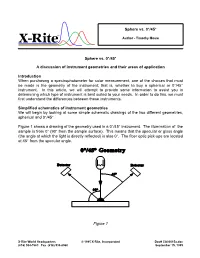

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

Convolution on the N-Sphere with Application to PDF Modeling Ivan Dokmanic´, Student Member, IEEE, and Davor Petrinovic´, Member, IEEE

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SIGNAL PROCESSING, VOL. 58, NO. 3, MARCH 2010 1157 Convolution on the n-Sphere With Application to PDF Modeling Ivan Dokmanic´, Student Member, IEEE, and Davor Petrinovic´, Member, IEEE Abstract—In this paper, we derive an explicit form of the convo- emphasis on wavelet transform in [8]–[12]. Computation of the lution theorem for functions on an -sphere. Our motivation comes Fourier transform and convolution on groups is studied within from the design of a probability density estimator for -dimen- the theory of noncommutative harmonic analysis. Examples sional random vectors. We propose a probability density function (pdf) estimation method that uses the derived convolution result of applications of noncommutative harmonic analysis in engi- on . Random samples are mapped onto the -sphere and esti- neering are analysis of the motion of a rigid body, workspace mation is performed in the new domain by convolving the samples generation in robotics, template matching in image processing, with the smoothing kernel density. The convolution is carried out tomography, etc. A comprehensive list with accompanying in the spectral domain. Samples are mapped between the -sphere theory and explanations is given in [13]. and the -dimensional Euclidean space by the generalized stereo- graphic projection. We apply the proposed model to several syn- Statistics of random vectors whose realizations are observed thetic and real-world data sets and discuss the results. along manifolds embedded in Euclidean spaces are commonly termed directional statistics. An excellent review may be found Index Terms—Convolution, density estimation, hypersphere, hy- perspherical harmonics, -sphere, rotations, spherical harmonics. in [14]. It is of interest to develop tools for the directional sta- tistics in analogy with the ordinary Euclidean. -

Minkowski Products of Unit Quaternion Sets 1 Introduction

Minkowski products of unit quaternion sets 1 Introduction The Minkowski sum A⊕B of two point sets A; B 2 Rn is the set of all points generated [16] by the vector sums of points chosen independently from those sets, i.e., A ⊕ B := f a + b : a 2 A and b 2 B g : (1) The Minkowski sum has applications in computer graphics, geometric design, image processing, and related fields [9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20]. The validity of the definition (1) in Rn for all n ≥ 1 stems from the straightforward extension of the vector sum a + b to higher{dimensional Euclidean spaces. However, to define a Minkowski product set A ⊗ B := f a b : a 2 A and b 2 B g ; (2) it is necessary to specify products of points in Rn. In the case n = 1, this is simply the real{number product | the resulting algebra of point sets in R1 is called interval arithmetic [17, 18] and is used to monitor the propagation of uncertainty through computations in which the initial operands (and possibly also the arithmetic operations) are not precisely determined. A natural realization of the Minkowski product (2) in R2 may be achieved [7] by interpreting the points a and b as complex numbers, with a b being the usual complex{number product. Algorithms to compute Minkowski products of complex{number sets have been formulated [6], and extended to determine Minkowski roots and powers [3, 8] of complex sets; to evaluate polynomials specified by complex{set coefficients and arguments [4]; and to solve simple equations expressed in terms of complex{set coefficients and unknowns [5]. -

Recognizing Surfaces

RECOGNIZING SURFACES Ivo Nikolov and Alexandru I. Suciu Mathematics Department College of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Abstract The subject of this poster is the interplay between the topology and the combinatorics of surfaces. The main problem of Topology is to classify spaces up to continuous deformations, known as homeomorphisms. Under certain conditions, topological invariants that capture qualitative and quantitative properties of spaces lead to the enumeration of homeomorphism types. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. The poster focuses on the main topological invariants of two-dimensional manifolds—orientability, number of boundary components, genus, and Euler characteristic—and how these invariants solve the classification problem for compact surfaces. The poster introduces a Java applet that was written in Fall, 1998 as a class project for a Topology I course. It implements an algorithm that determines the homeomorphism type of a closed surface from a combinatorial description as a polygon with edges identified in pairs. The input for the applet is a string of integers, encoding the edge identifications. The output of the applet consists of three topological invariants that completely classify the resulting surface. Topology of Surfaces Topology is the abstraction of certain geometrical ideas, such as continuity and closeness. Roughly speaking, topol- ogy is the exploration of manifolds, and of the properties that remain invariant under continuous, invertible transforma- tions, known as homeomorphisms. The basic problem is to classify manifolds according to homeomorphism type. In higher dimensions, this is an impossible task, but, in low di- mensions, it can be done. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. -

The Real Projective Spaces in Homotopy Type Theory

The real projective spaces in homotopy type theory Ulrik Buchholtz Egbert Rijke Technische Universität Darmstadt Carnegie Mellon University Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract—Homotopy type theory is a version of Martin- topology and homotopy theory developed in homotopy Löf type theory taking advantage of its homotopical models. type theory (homotopy groups, including the fundamen- In particular, we can use and construct objects of homotopy tal group of the circle, the Hopf fibration, the Freuden- theory and reason about them using higher inductive types. In this article, we construct the real projective spaces, key thal suspension theorem and the van Kampen theorem, players in homotopy theory, as certain higher inductive types for example). Here we give an elementary construction in homotopy type theory. The classical definition of RPn, in homotopy type theory of the real projective spaces as the quotient space identifying antipodal points of the RPn and we develop some of their basic properties. n-sphere, does not translate directly to homotopy type theory. R n In classical homotopy theory the real projective space Instead, we define P by induction on n simultaneously n with its tautological bundle of 2-element sets. As the base RP is either defined as the space of lines through the + case, we take RP−1 to be the empty type. In the inductive origin in Rn 1 or as the quotient by the antipodal action step, we take RPn+1 to be the mapping cone of the projection of the 2-element group on the sphere Sn [4]. -

The Sphere Packing Problem in Dimension 8 Arxiv:1603.04246V2

The sphere packing problem in dimension 8 Maryna S. Viazovska April 5, 2017 8 In this paper we prove that no packing of unit balls in Euclidean space R has density greater than that of the E8-lattice packing. Keywords: Sphere packing, Modular forms, Fourier analysis AMS subject classification: 52C17, 11F03, 11F30 1 Introduction The sphere packing constant measures which portion of d-dimensional Euclidean space d can be covered by non-overlapping unit balls. More precisely, let R be the Euclidean d vector space equipped with distance k · k and Lebesgue measure Vol(·). For x 2 R and d r 2 R>0 we denote by Bd(x; r) the open ball in R with center x and radius r. Let d X ⊂ R be a discrete set of points such that kx − yk ≥ 2 for any distinct x; y 2 X. Then the union [ P = Bd(x; 1) x2X d is a sphere packing. If X is a lattice in R then we say that P is a lattice sphere packing. The finite density of a packing P is defined as Vol(P\ Bd(0; r)) ∆P (r) := ; r > 0: Vol(Bd(0; r)) We define the density of a packing P as the limit superior ∆P := lim sup ∆P (r): r!1 arXiv:1603.04246v2 [math.NT] 4 Apr 2017 The number be want to know is the supremum over all possible packing densities ∆d := sup ∆P ; d P⊂R sphere packing 1 called the sphere packing constant. For which dimensions do we know the exact value of ∆d? Trivially, in dimension 1 we have ∆1 = 1. -

GEOMETRY Contents 1. Euclidean Geometry 2 1.1. Metric Spaces 2 1.2

GEOMETRY JOUNI PARKKONEN Contents 1. Euclidean geometry 2 1.1. Metric spaces 2 1.2. Euclidean space 2 1.3. Isometries 4 2. The sphere 7 2.1. More on cosine and sine laws 10 2.2. Isometries 11 2.3. Classification of isometries 12 3. Map projections 14 3.1. The latitude-longitude map 14 3.2. Stereographic projection 14 3.3. Inversion 14 3.4. Mercator’s projection 16 3.5. Some Riemannian geometry. 18 3.6. Cylindrical projection 18 4. Triangles in the sphere 19 5. Minkowski space 21 5.1. Bilinear forms and Minkowski space 21 5.2. The orthogonal group 22 6. Hyperbolic space 24 6.1. Isometries 25 7. Models of hyperbolic space 30 7.1. Klein’s model 30 7.2. Poincaré’s ball model 30 7.3. The upper halfspace model 31 8. Some geometry and techniques 32 8.1. Triangles 32 8.2. Geodesic lines and isometries 33 8.3. Balls 35 9. Riemannian metrics, area and volume 36 Last update: December 12, 2014. 1 1. Euclidean geometry 1.1. Metric spaces. A function d: X × X ! [0; +1[ is a metric in the nonempty set X if it satisfies the following properties (1) d(x; x) = 0 for all x 2 X and d(x; y) > 0 if x 6= y, (2) d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X, and (3) d(x; y) ≤ d(x; z) + d(z; y) for all x; y; z 2 X (the triangle inequality). The pair (X; d) is a metric space. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Flavors of Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 31,1997 Hyperbolic Geometry JAMES W. CANNON, WILLIAM J. FLOYD, RICHARD KENYON, AND WALTER R. PARRY Contents 1. Introduction 59 2. The Origins of Hyperbolic Geometry 60 3. Why Call it Hyperbolic Geometry? 63 4. Understanding the One-Dimensional Case 65 5. Generalizing to Higher Dimensions 67 6. Rudiments of Riemannian Geometry 68 7. Five Models of Hyperbolic Space 69 8. Stereographic Projection 72 9. Geodesics 77 10. Isometries and Distances in the Hyperboloid Model 80 11. The Space at Infinity 84 12. The Geometric Classification of Isometries 84 13. Curious Facts about Hyperbolic Space 86 14. The Sixth Model 95 15. Why Study Hyperbolic Geometry? 98 16. When Does a Manifold Have a Hyperbolic Structure? 103 17. How to Get Analytic Coordinates at Infinity? 106 References 108 Index 110 1. Introduction Hyperbolic geometry was created in the first half of the nineteenth century in the midst of attempts to understand Euclid’s axiomatic basis for geometry. It is one type of non-Euclidean geometry, that is, a geometry that discards one of Euclid’s axioms. Einstein and Minkowski found in non-Euclidean geometry a This work was supported in part by The Geometry Center, University of Minnesota, an STC funded by NSF, DOE, and Minnesota Technology, Inc., by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and by NSF research grants. 59 60 J. W. CANNON, W. J. FLOYD, R. KENYON, AND W. R. PARRY geometric basis for the understanding of physical time and space. In the early part of the twentieth century every serious student of mathematics and physics studied non-Euclidean geometry.