The Sphere Packing Problem in Dimension 8 Arxiv:1603.04246V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

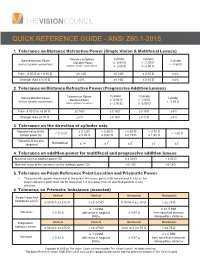

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Kepler and Hales: Conjectures and Proofs Dreams and Their

KEPLER AND HALES: CONJECTURES AND PROOFS DREAMS AND THEIR REALIZATION Josef Urban Czech Technical University in Prague Pittsburgh, June 21, 2018 1 / 31 This talk is an experiment Normally I give “serious” talks – I am considered crazy enough But this is Tom’s Birthday Party, so we are allowed to have some fun: This could be in principle a talk about our work on automation and AI for reasoning and formalization, and Tom’s great role in these areas. But the motivations and allusions go back to alchemistic Prague of 1600s and the (un)scientific pursuits of then versions of "singularity", provoking comparisons with our today’s funny attempts at building AI and reasoning systems for solving the great questions of Math, the Universe and Everything. I wonder where this will all take us. Part 1 (Proofs?): Learning automated theorem proving on top of Flyspeck and other corpora Learning formalization (autoformalization) on top of them Part 2 (Conjectures?): How did we get here? What were Kepler & Co trying to do in 1600s? What are we trying to do today? 2 / 31 The Flyspeck project – A Large Proof Corpus Kepler conjecture (1611): The most compact way of stacking balls of the same size in space is a pyramid. V = p 74% 18 Proved by Hales & Ferguson in 1998, 300-page proof + computations Big: Annals of Mathematics gave up reviewing after 4 years Formal proof finished in 2014 20000 lemmas in geometry, analysis, graph theory All of it at https://code.google.com/p/flyspeck/ All of it computer-understandable and verified in HOL Light: -

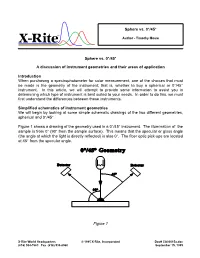

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

![Arxiv:1603.05202V1 [Math.MG] 16 Mar 2016 Etr .Itrue Peia Amnc 27 Harmonics Spherical Interlude: 3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2521/arxiv-1603-05202v1-math-mg-16-mar-2016-etr-itrue-peia-amnc-27-harmonics-spherical-interlude-3-512521.webp)

Arxiv:1603.05202V1 [Math.MG] 16 Mar 2016 Etr .Itrue Peia Amnc 27 Harmonics Spherical Interlude: 3

Contents Packing, coding, and ground states Henry Cohn 1 Packing, coding, and ground states 3 Preface 3 Acknowledgments 3 Lecture 1. Sphere packing 5 1. Introduction 5 2. Motivation 6 3. Phenomena 8 4. Constructions 10 5. Difficulty of sphere packing 12 6. Finding dense packings 13 7. Computational problems 15 Lecture 2. Symmetry and ground states 17 1. Introduction 17 2. Potential energy minimization 18 3. Families and universal optimality 19 4. Optimality of simplices 23 Lecture 3. Interlude: Spherical harmonics 27 1. Fourier series 27 2. Fourier series on a torus 29 3. Spherical harmonics 31 Lecture4. Energyandpackingboundsonspheres 35 arXiv:1603.05202v1 [math.MG] 16 Mar 2016 1. Introduction 35 2. Linear programming bounds 37 3. Applying linear programming bounds 39 4. Spherical codes and the kissing problem 40 5. Ultraspherical polynomials 41 Lecture 5. Packing bounds in Euclidean space 47 1. Introduction 47 2. Poisson summation 49 3. Linear programming bounds 50 4. Optimization and conjectures 52 Bibliography 57 i Packing, coding, and ground states Henry Cohn Packing, coding, and ground states Henry Cohn Preface In these lectures, we’ll study simple models of materials from several different perspectives: geometry (packing problems), information theory (error-correcting codes), and physics (ground states of interacting particle systems). These per- spectives each shed light on some of the same problems and phenomena, while highlighting different techniques and connections. One noteworthy phenomenon is the exceptional symmetry that is found in certain special cases, and we’ll examine when and why it occurs. The overall theme of the lectures is thus order vs. -

Recognizing Surfaces

RECOGNIZING SURFACES Ivo Nikolov and Alexandru I. Suciu Mathematics Department College of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Abstract The subject of this poster is the interplay between the topology and the combinatorics of surfaces. The main problem of Topology is to classify spaces up to continuous deformations, known as homeomorphisms. Under certain conditions, topological invariants that capture qualitative and quantitative properties of spaces lead to the enumeration of homeomorphism types. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. The poster focuses on the main topological invariants of two-dimensional manifolds—orientability, number of boundary components, genus, and Euler characteristic—and how these invariants solve the classification problem for compact surfaces. The poster introduces a Java applet that was written in Fall, 1998 as a class project for a Topology I course. It implements an algorithm that determines the homeomorphism type of a closed surface from a combinatorial description as a polygon with edges identified in pairs. The input for the applet is a string of integers, encoding the edge identifications. The output of the applet consists of three topological invariants that completely classify the resulting surface. Topology of Surfaces Topology is the abstraction of certain geometrical ideas, such as continuity and closeness. Roughly speaking, topol- ogy is the exploration of manifolds, and of the properties that remain invariant under continuous, invertible transforma- tions, known as homeomorphisms. The basic problem is to classify manifolds according to homeomorphism type. In higher dimensions, this is an impossible task, but, in low di- mensions, it can be done. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. -

A Computer Verification of the Kepler Conjecture

ICM 2002 Vol. III 1–3 · · A Computer Verification of the Kepler Conjecture Thomas C. Hales∗ Abstract The Kepler conjecture asserts that the density of a packing of congruent balls in three dimensions is never greater than π/√18. A computer assisted verification confirmed this conjecture in 1998. This article gives a historical introduction to the problem. It describes the procedure that converts this problem into an optimization problem in a finite number of variables and the strategies used to solve this optimization problem. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 52C17. Keywords and Phrases: Sphere packings, Kepler conjecture, Discrete ge- ometry. 1. Historical introduction The Kepler conjecture asserts that the density of a packing of congruent balls in three dimensions is never greater than π/√18 0.74048 .... This is the oldest problem in discrete geometry and is an important≈ part of Hilbert’s 18th problem. An example of a packing achieving this density is the face-centered cubic packing (Figure 1). A packing of balls is an arrangement of nonoverlapping balls of radius 1 in Euclidean space. Each ball is determined by its center, so equivalently it is a arXiv:math/0305012v1 [math.MG] 1 May 2003 collection of points in Euclidean space separated by distances of at least 2. The density of a packing is defined as the lim sup of the densities of the partial packings formed by the balls inside a ball with fixed center of radius R. (By taking the lim sup, rather than lim inf as the density, we prove the Kepler conjecture in the strongest possible sense.) Defined as a limit, the density is insensitive to changes in the packing in any bounded region. -

Sphere Packing, Lattice Packing, and Related Problems

Sphere packing, lattice packing, and related problems Abhinav Kumar Stony Brook April 25, 2018 Sphere packings Definition n A sphere packing in R is a collection of spheres/balls of equal size which do not overlap (except for touching). The density of a sphere packing is the volume fraction of space occupied by the balls. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ In dimension 1, we can achieve density 1 by laying intervals end to end. In dimension 2, the best possible is by using the hexagonal lattice. [Fejes T´oth1940] Sphere packing problem n Problem: Find a/the densest sphere packing(s) in R . In dimension 2, the best possible is by using the hexagonal lattice. [Fejes T´oth1940] Sphere packing problem n Problem: Find a/the densest sphere packing(s) in R . In dimension 1, we can achieve density 1 by laying intervals end to end. Sphere packing problem n Problem: Find a/the densest sphere packing(s) in R . In dimension 1, we can achieve density 1 by laying intervals end to end. In dimension 2, the best possible is by using the hexagonal lattice. [Fejes T´oth1940] Sphere packing problem II In dimension 3, the best possible way is to stack layers of the solution in 2 dimensions. This is Kepler's conjecture, now a theorem of Hales and collaborators. mmm m mmm m There are infinitely (in fact, uncountably) many ways of doing this! These are the Barlow packings. Face centered cubic packing Image: Greg A L (Wikipedia), CC BY-SA 3.0 license But (until very recently!) no proofs. In very high dimensions (say ≥ 1000) densest packings are likely to be close to disordered. -

An Overview of the Kepler Conjecture

AN OVERVIEW OF THE KEPLER CONJECTURE Thomas C. Hales 1. Introduction and Review The series of papers in this volume gives a proof of the Kepler conjecture, which asserts that the density of a packing of congruent spheres in three dimensions is never greater than π/√18 0.74048 . This is the oldest problem in discrete geometry and is an important≈ part of Hilbert’s 18th problem. An example of a packing achieving this density is the face-centered cubic packing. A packing of spheres is an arrangement of nonoverlapping spheres of radius 1 in Euclidean space. Each sphere is determined by its center, so equivalently it is a collection of points in Euclidean space separated by distances of at least 2. The density of a packing is defined as the lim sup of the densities of the partial packings formed by spheres inside a ball with fixed center of radius R. (By taking the lim sup, rather than lim inf as the density, we prove the Kepler conjecture in the strongest possible sense.) Defined as a limit, the density is insensitive to changes in the packing in any bounded region. For example, a finite number of spheres can be removed from the face-centered cubic packing without affecting its density. Consequently, it is not possible to hope for any strong uniqueness results for packings of optimal density. The uniqueness established by this work is as strong arXiv:math/9811071v2 [math.MG] 20 May 2002 as can be hoped for. It shows that certain local structures (decomposition stars) attached to the face-centered cubic (fcc) and hexagonal-close packings (hcp) are the only structures that maximize a local density function. -

Physical Interpretation of the 30 8-Simplexes in the E8 240-Polytope

Physical Interpretation of the 30 8-simplexes in the E8 240-Polytope: Frank Dodd (Tony) Smith, Jr. 2017 - viXra 1702.0058 248-dim Lie Group E8 has 240 Root Vectors arranged on a 7-sphere S7 in 8-dim space. The 12 vertices of a cuboctahedron live on a 2-sphere S2 in 3-dim space. They are also the 4x3 = 12 outer vertices of 4 tetrahedra (3-simplexes) that share one inner vertex at the center of the cuboctahedron. This paper explores how the 240 vertices of the E8 Polytope in 8-dim space are related to the 30x8 = 240 outer vertices (red in figure below) of 30 8-simplexes whose 9th vertex is a shared inner vertex (yellow in figure below) at the center of the E8 Polytope. The 8-simplex has 9 vertices, 36 edges, 84 triangles, 126 tetrahedron cells, 126 4-simplex faces, 84 5-simplex faces, 36 6-simplex faces, 9 7-simplex faces, and 1 8-dim volume The real 4_21 Witting polytope of the E8 lattice in R8 has 240 vertices; 6,720 edges; 60,480 triangular faces; 241,920 tetrahedra; 483,840 4-simplexes; 483,840 5-simplexes 4_00; 138,240 + 69,120 6-simplexes 4_10 and 4_01; and 17,280 = 2,160x8 7-simplexes 4_20 and 2,160 7-cross-polytopes 4_11. The cuboctahedron corresponds by Jitterbug Transformation to the icosahedron. The 20 2-dim faces of an icosahedon in 3-dim space (image from spacesymmetrystructure.wordpress.com) are also the 20 outer faces of 20 not-exactly-regular-in-3-dim tetrahedra (3-simplexes) that share one inner vertex at the center of the icosahedron, but that correspondence does not extend to the case of 8-simplexes in an E8 polytope, whose faces are both 7-simplexes and 7-cross-polytopes, similar to the cubocahedron, but not its Jitterbug-transform icosahedron with only triangle = 2-simplex faces.